полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

Stage-coach and Tavern Days

Our first conveyance of goods and persons was by water, and the word transportation was one of our sea terms applied to inland traffic. Mr. Ernst has pointed out that many sea terms besides the word barge have received a land use. “The conductor shouts his marine ‘All aboard,’ and railroad men tell of ‘shipping’ points that have nothing to do with navigation. We ship by rail, and out West they used to have ‘prairie schooners.’ Of late we go by ‘trolley,’ and that word is borrowed from the sailors. Our locomotives have a ‘pilot’ each, and even ‘freight’ has a marine origin.”

The first line of stages established between New York and Philadelphia made the trip in about three days. The stage was simply a Jersey wagon without springs. The quaint advertisement of the route appeared in the Weekly Mercury of March 8, 1759: —

“Philadelphia Stage Waggon and New York Stage Boat perform their stages twice a week. John Butler with his waggon sets out on Monday from his house at the sign of the ‘Death of the Fox’ in Strawberry Alley, and drives the same day to Trenton Ferry, where Francis Holman meets him, and the passengers and goods being shifted into the waggon of Isaac Fitzrandolph, he takes them to the New Blazing Star to Jacob Fitzrandolph’s the same day, where Rubin Fitzrandolph, with a boat well suited will receive them and take them to New York that night: John Butler, returning to Philadelphia on Tuesday with the passengers and goods delivered to him by Francis Holman, will set out again for Trenton Ferry on Thursday, and Francis Holman, &c., will carry his passengers and goods with the same expedition as above to New York.”

The driver of this flying machine, old Butler, was an aged huntsman who kept a kennel of hounds till foxes were shy of Philadelphia streets, when his old sporting companions thus made a place for him.

With such a magnificent road as the National Road, it was natural there should be splendid coaching upon it. At one time there were four lines of stage-coaches on the Cumberland Road: the National Line, Pioneer, Good Intent, and June Bug. Curiously enough, no one can find out, no one is left to tell, why or wherefore the latter absurd and undignified name was given. An advertisement of the “Pioneer Fast Stage Line” is given on page 270. Relays of horses were made every ten or twelve miles. It was bragged that horses were changed ere the coach stopped rocking. No heavy luggage was taken, and at its prime but nine passengers to a coach. These were on what was called Troy coaches. The Troy coach was preceded by a heavy coach built at Cumberland, and carrying sixteen persons, and a lighter egg-shaped vehicle made at Trenton; and it was succeeded by the famous Concord coach. Often fourteen coaches started off together loaded with passengers. The mail-coach had a horn; it left Wheeling at six in the morning, and twenty-four hours later dashed into Cumberland, one hundred and thirty-two miles away. The mail was very heavy. Sometimes it took three to four coaches to transport it; there often would be fourteen lock-bags and seventy-two canvas sacks.

The drivers had vast rivalry. Here, as elsewhere all over the country, the test of their mettle was the delivery of the President’s message. There was powerful reason for this rivalry; the letting of mail contracts hinged on the speed of this special delivery. Dan Gordon claimed he carried the message thirty-two miles in two hours and twenty minutes, changing teams three times. Dan Noble professed to have driven from Wheeling to Hagerstown, one hundred and eighty-five miles, in fifteen hours and a half.

The rivalry of drivers and coach-owners extended to passengers, who became violent partisans of the road on which they travelled, and a threatening exhibition of bowie knives and pistols was often made. When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was completed to Wheeling, these stage-coaches had their deathblow.

The expense of travelling in 1812 between Philadelphia and Pittsburg, a distance of two hundred and ninety-seven miles, was twenty dollars by stage with way-expenses of seven dollars, and it took six days. The expense by wagon was five dollars a hundred weight for persons and property, and the way-expenses were twelve dollars, for it took twenty days.

In England, in the prime days of coaching, rates were fourpence or fivepence a mile inside, and twopence or threepence outside. The highest fares were of course on the mail-coaches and fast day-coaches; the lower rates were on the heavy night-coaches.

At an early date there were good lines of conveyance between Boston and Providence, and from Providence to other towns. The early editions of old almanacs tell of these coaching routes. The New England Almanack for 1765 gave two routes to Hartford, the distances being given from tavern to tavern. The New England Town & County Almanack for 1769 announced a coach between Providence and Norwich, “a day’s journey only,” and two coaches a week between Providence and Boston, also performing this journey in a day. In 1793, Israel Hatch announced daily stages between the two towns; he had “six good coaches and experienced drivers,” and the fare was but a dollar. He closed his notice, “He is also determined, at the expiration of the present contract for carrying the mail from Providence to Boston, to carry it gratis, which will undoubtedly prevent any further under-biddings of the Envious.”

“The Envious” was probably Thomas Beal, whose rival carriages were pronounced “genteel and easy.” His price was nine shillings “and less if any other person will carry them for that sum.” When passenger steamboats were put on the route between Providence and New York these lines of coaches became truly important. Often twenty full coach-loads were carried each way each day. The editor of the Providence Gazette wrote with pride, “We were rattled from Providence to Boston in four hours and fifty minutes – if any one wants to go faster he may send to Kentucky and charter a streak of lightning.” But with speed came increased fares – three dollars a trip. This exorbitant sum soon produced a rival cheaper line – at two dollars and a half a ticket. The others then lowered to two dollars, and the two lines alternated in reduction till the conquered old line announced it would carry the first booked applicants for nothing. The new stage line then advertised that they would carry patrons free of expense, and furnish a dinner at the end of the journey. The old line was rich and added a bottle of wine to a like offer.

Mr. Shaffer, a fashionable teacher of dancing and deportment in Boston, an arbiter in social life, and man about town, had a gay ride on Monday to Providence, a good dinner, and the promised bottle of wine. On Tuesday he rode more gayly back to Boston, had his dinner and wine, and on Wednesday started to Providence again. With a crowd of gay young sparks this frolic continued till Saturday, when the rival coach lines compromised and signed a contract to charge thereafter two dollars a trip.

In 1818 all the lines in eastern Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and others in Maine and Rhode Island, were formed into a syndicate, the Eastern Stage Company; and it had an unusual career. The capital stock consisted of four hundred and twenty-five shares at a hundred dollars each. Curiously enough, the contracts and agreements signed at the time of the union do not ever mention its object; it might be a sewing-machine company, or an oil or ice trust. It had at once an enormous business, for it was born great. The profits were likewise enormous; the directors’ meetings were symposiums of satisfaction, and stockholders gloated over their incomes. In 1829 there were seventy-seven stage-coach lines from Boston; the fare to Albany (about two hundred miles) was six dollars, and eight dollars and seventy-five cents by the “Mail Line.” The fare to Worcester was two dollars; to Portland, eight dollars; to Providence, two dollars and a half. In 1832 there were one hundred and six coach lines from Boston. The Boston Traveller was started as a stage-coach paper in 1825, whence its name. Time-tables and stage-lists were issued by Badger and Porter from 1825 to 1836. After twelve years, the Eastern Stage Company was incorporated in New Hampshire, but even then luck was turning. There was no one shrewd enough to heed the warning which might have been heard through the land, “Look out for the engine,” and soon the assets of the stage company were as dust and ashes; everything was sold out at vast loss, and in 1838 – merely a score of years, not even “come of age” – the Eastern Stage Company ceased to exist. On its prosperous routes, during the first ten years, myriads of taverns had sprung up; vast brick stables had been built for the hundreds of horses, scores of blacksmiths’ forges had been set up, and some of these shops were very large. These buildings were closed as suddenly as they were built, and rotted unused.

This period of the brilliant existence of the Eastern Stage Company was also the date of the coaching age of England, given by Stanley Harris as from 1820 to 1840. The year 1836, which saw the publication of Pickwick, wherein is so fine a picture of old coaching days, was the culminating point of the mail-coach system. Just as it was perfected it was rendered useless by the railroad.

In the earliest colonial days, before the official appointment of any regular post-rider, letters were carried along the coast or to the few inland towns by chance travellers or by butchers who made frequent trips to buy and sell cattle. John Winthrop, of New London, sent letters by these butcher carriers.

In 1672 “Indian posts” carried the Albany winter mail. With a retrospective shiver we read a notice of 1730 that “whoever inclines to perform the foot-post to Albany this winter may make application to the Post-Master.” Lonely must have been his solitary journey up the solemn river, skating along under old Cro’ Nest.

The first regular mounted post from New York to Boston started January 1, 1673. He had two “port-mantles” which were crammed with letters, “small portable goods and divers bags.” It was enjoined that he must be active, stout, indefatigable, and honest. He changed horses at Hartford. He was ordered to keep an eye out for the best roads, best ways through forests, for ferries, fords, etc., to watch keenly for all fugitive servants and deserters, and to be kind to all persons travelling in his company. During the month that he was gone the mail was collected in a box in the office of the Colonial Secretary. The arrivals and departure of these posts were very irregular. In 1704 we read, “Our Philadelphia post (to New York) is a week behind, and not yet com’d in.”

In unusual or violent weather the slowness of mail carriage was appalling. Salem and Portsmouth are about forty miles apart. In March, 1716, the “post” took nine days for one trip between the two towns and eight days the other. He was on snowshoes, and he reported drifts from six to fourteen feet deep; but even so, four to five miles a day was rather minute progress.

It is pleasant to read in the Winthrop Letters and other correspondence of colonial days of “journeys with the Post.” Madam Knight rode with him, as did many another fair traveller with his successors at later dates. A fragment of a journal of a young college graduate, written in 1790, tells of “over-taking the Post, who rode with six Dames, neither young nor fair, from Hartford to Boston.” He tells that the patient Squire of Dames was rather surly when joked about his harem. Mrs. Quincy tells of travelling, when she was a little girl, with the Post, who occupied his monotonous hours by stocking-knitting.

The post-riders, whose advertisements (one of which is here shown) can be found in many old-time newspapers, were private carriers. They “Resolv’d to ride Post for the good of the Publick,” etc. They were burdened by law with restrictions, which they calmly evaded, for they materially decreased the government revenue in sealed mail-matter, though they were supposed to be merchandise carriers only.

In 1773, Hugh Finlay was made postal surveyor by the British government of the mail service from Quebec, Canada, to St. Augustine, Florida. He made a very unfavorable report of postal conditions. He declared that postmasters often had no offices, that tavern taprooms and family rooms in private houses were used as gathering places for the mail. Letters were thrown carelessly on an open table or tavern bar, for all comers to pull over till the owners called; and fresh letters were irregularly forwarded. The postmaster’s salary was paid according to the number of letters he handled, and of course the private conveyance of letters sadly diminished his income. Private mail-carriage was forbidden by law, but the very government post-riders were the chief offenders. Persons were allowed to carry merchandise at their own rates for their own profit, so post-riders, wagon-drivers, butchers, ship captains, or any one could carry large sealed letters, provided they were tied to any bundle or box. Sham bundles of paper or straw, weighing little, were thus used as kite-tails to the letters. The government post-rider between Newport and Boston took twenty-six hours to go eighty miles, carried all way-letters to his own profit, and bought and sold on commission. If he had been complained of, the informer was in danger of tarring and feathering. It was deemed all a part of the revolt of the provinces against “slavery and oppression.” The rider between Saybrook and New York had been in his calling forty-six years. He carried on a money exchange to his own profit, and pocketed all way-postage. He superintended the return of horses for travellers; and Finlay says he was coolly waiting, when he saw him, for a yoke of oxen that he was going to transfer for a customer. No wonder the mails were slow and uncertain.

In 1788 it took four days for mail to go from New York to Boston – in winter much longer. George Washington died on the 14th of December, 1799. As an event of universal interest throughout the nation, the news was doubtless conveyed with all speed possible by fleetest messenger. The knowledge of this national loss was not known in Boston till December 24. Two years later there was a state election in Massachusetts of most profound interest, when party feeling ran high. It took a month, however, to get in all the election returns, even in a single state.

The first advertisement or bill of the first coaching line between Boston and Portsmouth reads thus: —

“For the Encouragement of Trade from Portsmouth to Boston“A Large Stage Chair,“With two horses well equipped, will be ready by Monday the 20th inst. to start out from Mr. Stavers, Inn-holder at the sign of the Earl of Halifax, in this town for Boston, to perform once a week; to lodge at Ipswich the same night; from thence through Medford to Charlestown Ferry; to tarry at Charlestown till Thursday morning, so as to return to this town next day: to set out again the Monday following: It will be contrived to carry four persons besides the driver. In case only two persons go, they may be accommodated to carry things of bulk and value to make a third or fourth person. The Price will be Thirteen Shillings and Six Pence sterling for each person from hence to Boston, and at the same rate of conveyance back again; though under no obligation to return in the same week in the same manner.

“Those who would not be disappointed must enter their names at Mr. Stavers’ on Saturdays, any time before nine in the evening, and pay one half at entrance, the remainder at the end of the journey. Any gentleman may have business transacted at Newbury or Boston with fidelity and despatch on reasonable terms.

“As gentlemen and ladies are often at a loss for good accommodations for travelling from hence, and can’t return in less than three weeks or a month, it is hoped that this undertaking will meet with suitable encouragement, as they will be wholly freed from the care and charge of keeping chairs and horses, or returning them before they had Finished their business.

“Portsmouth, April, 1761.”

A picture and account of the Stavers Inn are given on page 176.

These stages ran throughout the winter, except in bad weather, and the fare was then three dollars a trip. This winter trip was often a hard one. We read at one time of the ferries being so frozen over that travellers had to make a hundred-mile circuit round by Cambridge. This line of stages prospered; and two years later “The Portsmouth Flying Stage-coach,” which held six “insides,” ran with four or six horses. The fare was the same.

On this Stavers line were placed the first mail-coaches under the English crown. When Finlay (the post-office surveyor just referred to) examined the mail-service in the year 1773, he found these mail-coaches running between Boston and Portsmouth. Mr. Ernst says, “The Stavers mail-coach was stunning, used six horses in bad weather, and never was late.” These coaches were built by Paddock, the Boston coach-builder and Tory. Stavers also was a Tory, and during the Revolution both fled to England, and may have carried the notion of the mail-coach across the sea. At any rate the first English mail-coach was not put on the road till 1784; it ran between Bristol and London. It was started by a theatrical manager named Palmer, office work or coaching. The service was very imperfect and far from speedy.

Herbert Joyce, historian of the British post-office, says, “In 1813 there was not a single town in the British kingdom at the post-office of which absolutely certain information could have been obtained as to the charge to which a letter addressed to any other town would be subject.” The charge was regulated by the distance; but distances seemed movable, and the letter-sender was wholly at the mercy of the postmaster. The government of the United States early saw the injustice of doubt in these matters, and Congress ordered a careful topographical survey, in 1811-12, of the post-road from Passamaquoddy to St. Mary’s, and also established our peerless corps of topographical engineers. Foreigners were much impressed with the value of this survey, and an old handkerchief, printed in 1815 by R. Gillespie, at “Anderston Printfield near Glasgow,” proves that the practical effects of the survey were known in England before the English people had a similar service.

This handkerchief gives an interesting statement of postal rates and routes at the beginning of this century. Around the edge is a floral border, with the arms of the United States, the front and reverse of the dollar of 1815, a quartette of ships of war, and portraits of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and “Maddison” intertwined.

Its title is “A Geographical View of All the Post Towns in the United States of America and Their Distance from Each Other According to the Establishment of the Postmaster General in the Year 1815.” By an ingenious arrangement of the towns on the main coast line and those on the cross post-roads, the distance from one of these points to any other could easily be ascertained. The “main line of post towns” extended “from Passamaquoddy in the District of Maine to Sunbury in the State of Georgia.”

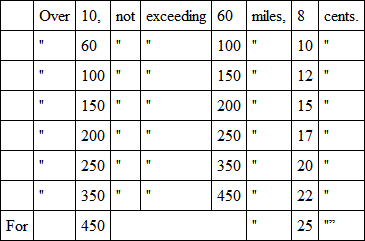

The object in publishing such a table as this was to make a durable record by which it was possible for the people to compute easily and with a handy helper what the cost of postage on letters would be. The following “rates of postage” are given on the old handkerchief: —

“Single Letter conveyed by land for any distance not exceeding 10 miles, 6 cents.

Double letters are charged double; and triple letters, three times these rates, and a packet weighing one ounce avoirdupois at the rate of four single letters.

Let us compare conditions in these matters in America with those in Scotland. While England had, in the first half of the eighteenth century, coaches in enough number that country folk knew what they looked like, Scotland was barren not only of coaches but of carriages. In 1720 there were no chariots or chaises north of the Tay. Not till 1749 was there a coach between Edinburgh and Glasgow; this journey of forty-six miles could, by the end of the century, be done in twelve hours. In 1754 there was once a month a coach from Edinburgh to London; it took twelve to sixteen days to accomplish this journey, and was so perilous that travellers made their wills before setting out. There were few carts and no such splendid wagons as our Conestogas. Cadgers carried creels of goods on horseback; and sledges, or creels borne on the backs of women, were the means of transportation in northern Scotland until the end of the eighteenth century. These sledges had tumbling wheels of solid wood a foot and a half in diameter, revolving with the wooden axletree, and held little more than a wheelbarrow.

Scotch inns were as bad as the roads; “mean hovels with dirty rooms, dirty food, dirty attendants.” Servants without shoes or stockings, greasy tables with no cloths, butter thick with cows’ hairs, no knives and forks, a single drinking-cup for all at the table, filthy smells and sights, were universal; and this when English inns were the pleasantest places on earth.

Mail-carriage was even worse than personal transportation; hence letter-writing was not popular. In 1746 the London mail-bag once carried but a single letter from Edinburgh. So little attention was paid to the post that as late as 1728 the letters were sometimes not taken from the mail bag, and were brought back to their original starting place. Scotland was in a miserable state of isolation and gloom until the Turnpike Road Act was passed; the building of good roads made a complete revolution of all economic conditions there, as it has everywhere.

The first railway in America was the Quincy Railroad, or the “Experiment” Railroad, built to carry stones to Bunker Hill Monument. A tavern-pitcher, commemorative of this Quincy road, is shown here. Two views of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, printed on plates and platters in rich dark blue, are familiar to china collectors. One shows a stationary engine at the top of a hill with a number of little freight cars at a very singular angle going down a steep grade. The other displays a primitive locomotive with coachlike passenger cars.

All the first rail-cars were run by horse-power.

Peter Parley’s First Book on History says, in the chapter on Maryland: —

“The people are building what is called a railroad. This consists of iron bars laid down along the ground and made fast, so that carriages with small wheels may run upon them with facility. In this way one horse will be able to draw as much as ten horses on a common road. A part of the railroad is already done, and if you choose to take a ride upon it you can do so. You enter a car something like a stage, and then you will be drawn along by two horses at a speed of twelve miles per hour.”

The horse-car system, in its perfection, did not prevail until many years after the establishment of steam cars. It is curious to note how suddenly, in our own day, the horse cars were banished by cars run by electricity; as speedily as were stage-coaches cast aside by steam. A short time ago a little child of eight years came running to me in much excitement over an unusual sight she had seen in a visit to a small town – “a trolley car dragged by horses.”

Many strange plans were advanced for the new railways. I have seen a wood-cut of a railway-coach rigged with masts and sails gayly running on a track. I don’t know whether the inventor of this wind-car ever rigged his car-boat and tried to run it. Another much-derided suggestion was that the motive power should be a long rope or chain, and the notion was scorned, but we have lived to see many successful lines of cars run by cable.

Kites and balloons also were seriously suggested as motive powers. It was believed that in a short time any person would be permitted to run his own private car or carriage over the tracks, by paying toll, as a coach did on a turnpike.

The body of the stage-coach furnished the model for the first passenger cars on the railway. A copy is here given of an old print of a train on the Veazie Railroad, which began to run from Bangor, Maine, in 1836. The road had two locomotives of Stevenson’s make from England. They had no cabs when they arrived here, but rude ones were attached. They burned wood. The cars were also English; a box resembling a stage-coach was placed on a rude platform. Each coach carried eight people. The passengers entered the side. The train ran about twelve miles in forty minutes. The rails, like those of other railroads at the time, were of strap-iron spiked down. These spikes soon rattled loose, so each engine carried a man with a sledge hammer, who watched the track, and when he spied a spike sticking up he would reach down and drive it home. These “snake heads,” as the rolled-up ends of the strap-iron were called, sometimes were forced up through the cars and did great damage. “Snake heads” were as common in railway travel as snags in the river in early steamboating.