полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

Stage-coach and Tavern Days

Horseflesh was so plentiful that “no one walked save a vagabond or a fool.” Doubtless our national characteristic of never walking a step when we can ride dates from the days “when we lived under the King.” Driving alone, that is, a man or woman driving for pleasure alone, without a driver or post-boy, is an American fashion. It was carried back to Europe by both the French and English officers who were here in Revolutionary times. The custom was noted with approval by the French in their various books and letters on this country. They also, La Rochefoucauld among them, praised our roads.

Mr. Ernst, an authority upon transportation and postal matters, believes that our roads in the northern provinces, on the whole, were excellent. He says that the actual cost of the roads as contained in Massachusetts records proves that the notion that our New England roads were wretched is not founded on fact. He notes our great use of pleasure carriages as a proof of good roads; in 1753 Massachusetts had about seven such carriages to every thousand persons. The English carriages were very heavy. In America we adopted the light-weight continental carriages – because our roads were good.

The corduroy road was one of the common road improvements made to render the roads passable by carts and stage-wagons. Marshy places and chuck-holes were filled up with saplings and logs from the crowded forests, and whole roads were made of logs which were cut in lengths about ten or twelve feet long, and laid close to each other across the road. Many corduroy roads still remain, and some are veritable antiques; in Canada they still are built. A few years ago I rode many miles over one in a miner’s springless cart over the mountains of the Alexandrite range in upper Canada, and I deem it the most trying ordeal I ever experienced.

As soon as there were roads, there were ferries and bridges. Out from Boston to the main were ferries in 1639 to Chelsea and Charlestown. There was a “cart-bridge” built by Boston and Roxbury over Muddy River in 1633. There was a “foot-bridge” also at Scituate, and at Ipswich in 1635. In 1634 a “horse-bridge” was built at Neponset, and others soon followed. These had a railing on one side only. It was a great step when the “Bay” granted fifty pounds to Lynn for a cart-bridge where there had been only a ferry. After King Philip’s War, cart-bridges multiplied; there was one in Scituate, one in Bristol, one in Cambridge.

These early bridges of provincial days were but insecure makeshifts in many cases, miserable floating bridges being common across the wide rivers. In England bridges were poor also. We were to be early in fine bridge-building, and to excel in it as we have to this day. We were also in advance of the mother country in laying macadamized roads, in the use of mail-coaches, in modes of steam travel by water, just as we were in using flintlock firearms, and other advanced means of warfare.

The Charles River between Boston and Charlestown was about as wide at the point where the old ferry crossed as was the Thames at London Bridge, and Americans were emulative of that structure. Much talking and planning was done, but no bridge was built across the Charles till after the Revolution. Then Lemuel Cox, a Medford shipwright, planned and built a successful bridge in 1786. It was the longest bridge in the world, and deemed a triumph of engineering. The following year he built the Malden Bridge, then the fine Essex Bridge at Salem. In 177 °Cox went to Ireland and built a bridge nine hundred feet long over the deep Foyle at Londonderry, Ireland. This was another American victory, for the great English engineer, Milne, had pronounced the deed impossible. This bridge was of American oak and pine, and was built by Maine lumbermen and carpenters.

According to the universal “Gust of the Age” – as Dr. Prince said – the aid of the Muses was called in to celebrate the opening of the Charlestown Bridge. This took place on the anniversary of the battle of Bunker Hill, and a vast feast was given. Broadsides were distributed bearing “poems” as long as the bridge. Here are a few specimen verses: —

“I sing the day in which the BridgeIs finished and done.Boston and Charlestown lads rejoiceAnd fire your cannon guns.“The Bridge is finished now I sayEach other bridge outviesFor London Bridge compared with oursAppears in dim disguise.“Now Boston Charlestown nobly joinAnd roast a fatted OxOn noted Bunker Hill combineTo toast our Patriot Cox.“May North and South and Charlestown allAgree with one consentTo love each one like Indian’s rumOn publick good be bent.”A perfect epidemic of bridge-building broke out all over the states. In our pride we wished to exhibit our superiority over the English everywhere. Throughout Maryland, Pennsylvania, and upper Virginia, fine wooden and stone bridges were built. On all the turnpikes the bridges equalled the roads. Many of those bridges still are in use. The oldest suspension bridge in America, the “chain-bridge” at Newburyport, Massachusetts, is still standing. A picture of it here is shown. It is a graceful bridge, and its lovely surroundings add to its charm.

The traveller Melish noted specially, in 1812, the fine Trenton Bridge, “very elegant, nine hundred and seventy feet long, with two carriage ways”; the West Boston Bridge “three thousand feet long, with a causeway three thousand more”; the Schuylkill Bridge, which cost over two hundred thousand dollars.

So bad was the state of English roads at the end of the eighteenth century that it took two days’ and three nights’ incessant travel to get from Manchester to Glasgow. The crossroads were worse. In many cases when mail-coaches had been granted, the roads were too poor to receive them. The ruts, or rather trenches, were up to the axletrees. When a mail-coach was put on the Holyhead Road in 1808, twenty-two townships were indicted for having their roads in a dangerous condition. This road had vast sums spent upon it; in the six years succeeding 1825 it had £83,700 for “improvements,” and repairs were paid by the tolls. Its condition now is very mean, grass-grown in places, and in ill-repair.

The system of road-making known as macadamizing received its name from Mr. Loudon McAdam, who came to England from America in 1783 at a time when many new roads were being made in Scotland. These roads he studied and in 1816 became road surveyor in Bristol, where he was able to carry his principles into practice. The leading feature of his system was setting a limit in size and weight to the stones to be used on the roads, the weight limit being six ounces; also to prohibit any mixture of clay, earth, or chalk with the stone. Similar roads had been made in Pennsylvania long before they were laid in England, and had been tested; and without doubt McAdam simply followed methods he had seen successfully used in America. Among others the Salem and Boston Turnpike, the Essex Turnpike (between Salem and Andover), and the Newburyport Turnpike, all macadamized roads, were in successful operation before Telford and McAdam had perfected their systems.

McAdam’s son, Sir James McAdam, was General Superintendent of Metropolitan Roads in England when, as he expressed it, “the calamity of railways fell upon us.” This “calamity” brought these results: coaches ran less frequently, and all horse-carriage decreased, toll receipts diminished, many turnpike roads became bankrupt and passed into possession of towns and parishes, and are kept in scarcely passable repair. Many English macadamized roads are only kept in order in half, while the other part of the road bears weeds and grass.

The first American turnpike was not in Pennsylvania, as is usually stated, but in Virginia. It connected Alexandria (then supposed to be the rising metropolis) with “Sniggers and Vesta’s Gaps” – that is, the lower Shenandoah. This turnpike was started in 1785-86, and Thomas Jefferson pronounced it a success. In 1787 the Grand Jury of Baltimore reported the state of the country roads as a public grievance, and the Frederick, Reisterstown, and York roads were laid out anew by the county as turnpikes with toll-gates. In 1804 these roads were granted to corporate companies. Others soon followed, till all the main roads through Maryland were turnpikes.

The most important early turnpike was the one known as the National Road because it was made by the national government. It extended at first from Cumberland to Wheeling, and was afterward carried farther. When first opened it was a hundred and thirty miles long, and cost one and three-quarters millions of dollars. Proposed in Congress in 1797, an act providing for its construction was passed nine years later, and the first mail-coach carrying the United States mail travelled over it in August, 1818. It was a splendid road, sixty feet wide, of stone broken to pass through a three-inch ring, then covered with gravel and rolled down with an iron roller. One who saw the constructive work on it wrote: —

“That great contractor, Mordecai Cochran, with his immortal Irish brigade – a thousand strong, with their carts, wheelbarrows, picks, shovels, and blasting-tools, graded the commons and climbed the mountain side, leaving behind them a roadway good enough for an emperor.”

Over this National Road journeyed many congressmen to and from Washington; and the mail contractors, anxious to make a good impression on these senators and representatives, and thus gain fresh privileges and large appropriations, ever kept up a splendid stage line. It was on this line that the phrase “chalking his hat” – or the free pass system – originated. Mr. Reeside, the agent of the road, occasionally tendered a free ride to some member of Congress, and devised a hieroglyphic which he marked in chalk on the representative’s hat, in order that none of his drivers should be imposed upon by forged passes.

The intent was to extend this road to St. Louis. From Cumberland to Baltimore the cost of construction fell on certain banks in Maryland, which were rechartered on condition that they completed the road. Instead of being a burden to them, it became a lucrative property, yielding twenty per cent profit for many years. Not only was this road excellently macadamized, but stone bridges were built for it over rivers and creeks; the distances were indexed by iron mileposts, and the toll-houses were supplied with strong iron gates.

On other turnpikes throughout the country Irish laborers were employed to dig the earth and break the stone. Until this time Irish immigration had been slight in this country, and in many small communities where the new turnpikes passed the first Irish immigrants were stared at as curiosities.

The story of the old Mohawk Turnpike is one of deep interest. After the Revolution a great movement of removal to the West swept through New England; in the winter of 1795, in three days twelve hundred sleighs passed through Albany bearing sturdy New England people as settlers to the Genesee Valley. Others came on horseback, prospecting, – farmers with well-filled saddle bags and pocketbooks. Among those thrifty New Englanders were two young men named Whetmore and Norton, from Litchfield, Connecticut, who noted the bad roads over which all this travel passed; and being surveyors, they planned and eventually carried out a turnpike. The first charter, granted in 1797, was for the sixteen miles between Albany and Schenectady. When that was finished, in 1800, the turnpike from Schenectady to Utica, sixty-eight miles long, was begun. The public readily subscribed to build these roads; the flow of settlers increased; the price of land advanced; everywhere activity prevailed. The turnpike was filled with great trading wagons; there was a tavern at every mile on the road; fifty-two within fifty miles of Albany, but there were not taverns enough to meet the demand caused by the great travel. Eighty or one hundred horses would sometimes be stabled at a single tavern. All teamsters desired stable-room for their horses; but so crowded were the tavern sheds that many carried sheets of oilcloth to spread over their horses at night in case they could not find shelter.

Common wagons with narrow tires cut grooves in the macadamized road; so the Turnpike Company passed free all wagons with tires six inches broad or wider.

These helped to roll down the road, and by law were not required to turn aside on the road save for wagons with like width of tire.

The New York turnpikes were traversed by a steady procession of these great wagons, marked often in great lettering with the magic words which were in those days equivalent to Eldorado or Golconda – namely, “Ohio,” or “Genesee Valley.” Freight rates from Albany to Utica were a dollar for a hundred and twelve pounds.

In 1793 the old horse-path from Albany over the mountains to the Connecticut River was made wide enough for the passage of a coach. Westward from Albany a coach ran to Whitestone, Oneida County. In 1783 the first regular mail was delivered at Schenectady, nearly a century after its settlement. Soon the “mail-stages” ran as far as Whitestone. An advertisement of one of these clumsy old mail-stages is here shown. We need not wonder at the misspelling in this advertisement of the name of the town, for in 1792 the Postmaster-general advertised for contracts to carry the mail from “Connojorharrie to Kanandarqua.”

There were twelve gates on the “pike” between Utica and Schenectady; at Schenectady, Crane’s Village, Caughnawaga (now Fonda), Schenck’s Hollow, east of Wagner’s Hollow road, Garoga Creek, St. Johnsville, East Creek Bridge, Fink’s Ferry, Herkimer, Sterling, Utica. These gates did not swing on hinges, but were portcullises; a custom in other countries referred to in the beautiful passage in the Psalms, “Lift up your heads, O ye gates,” etc.

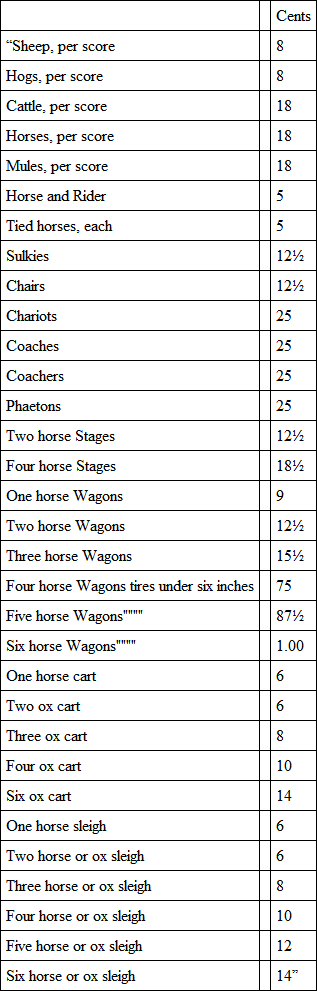

On every toll-gate was a board with the rates of toll painted thereon. Mr. Rufus A. Grider gives the list of rates on the Schenectady and Utica Turnpike, a distance of sixty-eight miles. They seem to me exceedingly high.

The toll-board which hung for many years on a bridge over the Susquehanna River at Sidney, New York, is shown on page 233.

Sometimes sign-boards were hung on bridges. One is shown on page 239 which hung for many years on the wooden bridge at Washington’s Crossing at Taylorsville, Pennsylvania, on the Bucks County side. It was painted by Benjamin Hicks, of Newtown, a copy of Trumbull’s picture of Washington crossing the Delaware. It was thrown in the garret of a store at Taylorsville, and rescued by Mr. Mercer for the Bucks County Historical Society.

The turnpike charters and toll-rates have revealed one thing to us, that all single-horse carriages were two-wheeled, such as the sulky, chair, chaise; while four-wheeled carriages always had at least two horses.

Citizens and travellers deeply resented these tolls, and ofttimes rose up against the payment. A toll-keeper in Pelham, Massachusetts, awoke one morning to find his gate gone. A scrawled bit of paper read: —

“The man who stopped the boy when going to the mill,Will find his gate at the bottom of the hill.”CHAPTER XI

PACKHORSE AND CONESTOGA WAGON

Our predecessors, the North American Indians, had no horses. An early explorer of Virginia said that if the country had horses and kine and were peopled with English, no realm in Christendom could be compared with it. The crude means of overland transportation common to all savages, the carrying of burdens on the back by various strappings, was the only mode known.

Travel by land in the colonies was for many years very limited in amount, and equally hazardous and inconvenient. Travel by boat was so greatly preferred that most of the settlements continued to be made on the banks of rivers and along the sea-coast. Even perilous canoes were preferable to the miseries of land travel.

We were slow in abandoning our water travel and water transportation. Water lines controlled in the East till 1800, in the West till 1860, and have now great revival.

Transportation was wholly done by water. When horses multiplied, merchandise was drawn short distances in the winter time on crude sledges. Packhorses were in common use in England and on the Continent, and the scrubby, enduring horses raised here soon were used as packhorses. Their use lingered long over the Alleghany Mountains, as it did on the mountains of the Pacific coast; in fact the advance guard of inland commerce in America has always employed packhorses.

The first appearance of the Conestoga wagon in history (though the wagons were not then called by that name) was in 1755, when General Braddock set out on his ill-fated expedition to western Pennsylvania. There led thither no wagon-road, simply an Indian trail for packhorses. Braddock insisted strenuously to the Pennsylvania Assembly upon obtaining their assistance in widening the trail to a wagon-road, and also to secure one hundred and fifty wagons for the army. The cutting of the road was done, but when returns were made to Braddock at Frederick, Maryland, only twenty-five wagons could be obtained. Franklin said it was a pity the troops had not been landed in Philadelphia, since every farmer in the country thereabouts had a wagon. At Braddock’s earnest solicitation, Franklin issued an ingenious and characteristic advertisement for one hundred and fifty four-horse wagons, and fifteen hundred saddle- or packhorses, for the use of this army. The value of transportation facilities at the time is proved by Franklin’s terms of payment, namely: fifteen shillings a day for each wagon with four horses and driver, and two shillings a day for horse with saddle or pack. Franklin agreed that the owners should be fairly compensated for the loss of these wagons and horses if they were not returned, and was eventually nearly ruined by this stipulation. For the battle at Braddock’s Field was disastrous to the English, and the claims of the farmers against Franklin amounted to twenty thousand pounds. Upon his appeal these claims were paid by the Government under order of General Shirley. Franklin gathered these wagons and horses in York and Lancaster counties, Pennsylvania, and I doubt if York and Lancaster, England, would have been as good fields at that date.

Braddock’s trail became the famous route for crossing the Alleghany Mountains for the principal pioneers who settled southwestern Pennsylvania and western Virginia, and all their effects were carried to their new homes on packhorses. The only wealth acquired in the wilds by these pioneers was peltry and furs, and each autumn a caravan of packhorses was sent over the mountains bearing the accumulated spoils of the neighborhood, under the charge of a master driver and three or four assistants. The horses were fitted with pack-saddles, to the hinder part of which was fastened a pair of hobbles made of hickory withes; and a collar with a bell was on each horse’s neck. The horses’ feed of shelled corn was carried in bags destined to be filled with alum salt for the return trip; and on the journey down, part of this feed was deposited for the use of the return caravan. Large wallets filled with bread, jerked bear’s meat, ham, and cheese furnished food for the drivers. At night the horses were hobbled and turned out into the woods or pasture, and the bells which had been muffled in the daytime were unfastened, to serve as a guide to the drivers in the morning. The furs were carried to and exchanged first at Baltimore as a market; later the carriers went only to Frederick; then to Hagerstown, Oldtown, and finally to Fort Cumberland. Iron and steel in various forms, and salt, were the things most eagerly desired by the settlers. Each horse could carry two bushels of alum salt, each bushel weighing eighty-four pounds. Not a heavy load, but the horses were scantily fed. Sometimes an iron pot or kettle was tied on either side on top of the salt-bag.

Ginseng, bears’ grease, and snakeroot were at a later date collected and added to the furs and hides. The horses marched in single file on a road scarce two feet wide; the foremost horse was led by the master of the caravan, and each successive horse was tethered to the pack-saddle of the one in front. Other men or boys watched the packs and urged on laggard horses.

I do not know the exact mode of lading these packhorses. An English gentlewoman named Celia Fiennes rode on horseback on a side-saddle over many portions of England in the year 1695. She thus describes the packhorses she saw in Devon and Cornwall: —

“Thus harvest is bringing in, on horse backe, with sort of crookes of wood like yokes on either side; two or three on a side stands up in which they stow ye corne, and so tie it with cords; but they cannot so equally poise it but ye going of ye horse is like to cast it down sometimes on ye one side sometimes on ye other, for they load them from ye neck to ye taile, and pretty high, and are forced to support it with their hands so to a horse they have two people women as well as men.”

At a later date this packhorse system became that of common carriers. Five hundred horses at a time, after the Revolution, could be seen winding over the mountains. At Lancaster, Harrisburg, Shippensburg, Bedford, Fort Pitt, and other towns were regular packhorse companies. One public carrier at Harris Ferry in 1772 had over two hundred horses and mules. When the road was widened and wagons were introduced, the packhorse drivers considered it an invasion of their rights and fiercely opposed it.

It is interesting to note that the trail of the Indians and the horse-track of these men skilled only in woodcraft were the ones followed in later years by trained engineers in laying out the turnpikes and railroads.

We are prone to pride ourselves in America on many things which we had no part in producing, on some which are in no way distinctive, and on a few which are not in the highest sense to our credit. Of the Conestoga wagon as a perfect vehicle of transportation and as an important historical factor we can honorably and rightfully be proud. It was a truly American product evolved and multiplied to fit, perfectly, existing conditions. Its day of usefulness is past, few ancient specimens exist; and little remains to remind us of it; the derivative word stogey, meaning hard, enduring, tough, is a legacy. Stogeys – shoes – are tough, coarse, leather footwear; and the stogey cigar was a great, heavy, coarse cigar, originally, it is said, a foot long, made to fit the enduring nerves and appetite of the Conestoga teamsters.

This splendid wagon was developed in Pennsylvania by topographical conditions, by the soft soil, by trade requirements, and by native wit. It was the highest type of a commodious freight-carrier by horse power that this or any country has ever known; it was called the Conestoga wagon from the vicinity in which they were first in common use.

These wagons had a boat-shaped body with curved canoe-shaped bottom which fitted them specially for mountain use; for in them freight remained firmly in place at whatever angle the body might be. This wagon body was painted blue or slate-color and had bright vermilion red sideboards. The rear end could be lifted from its sockets; on it hung the feed-trough for the horses. On one side of the body was a small tool-chest with a slanting lid. This held hammer, wrench, hatchet, pincers, and other simple tools. Under the rear axletree were suspended a tar-bucket and water-pail.

In the interesting and extensive museum of old-time articles of domestic use gathered intelligently by the Historical Society of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, are preserved some of the wagon grease-pots or Tar-lodel, which formed part of the furniture of the Conestoga wagon. A tree section about a foot long and six inches in diameter was bored and scraped out to make a pot. The outer upper rim was circumscribed with a groove, and fitted with leather thongs, by which it was hung to the axle of the wagon. Filled with grease and tar it was ever ready for use. Often a leather Tar-lodel took the place of this wooden grease-pot. The wheels had broad tires, sometimes nearly a foot broad. The wagon bodies were arched over with six or eight bows, of which the middle ones were the lowest. These were covered with a strong, pure-white hempen cover corded down strongly at the sides and ends. These wagons could be loaded up to the top of the bows and carried four to six tons each, – about a ton’s weight to each horse.