полная версия

полная версияThe Expositor's Bible: The Book of Daniel

Once more Daniel was terrified, remained silent, and fixed his eyes on the ground, until one like the sons of men touched his lips, and then he spoke to apologise for his timidity and faintheartedness.

A third time the vision touched, strengthened, blessed him, and bade him be strong. "Knowest thou," the angel asked, "why I am come to thee? I must return to fight against the Prince of Persia, and while I am gone the Prince of Greece [Javan] will come. I will, however, tell thee what is announced in the writing of truth, the book of the decrees of heaven, though there is no one to help me against these hostile princes of Persia and Javan, except Michael your prince."

The difficulties of the chapter are, as we have said, of a kind that the expositor cannot easily remove. I have given what appears to be the general sense. The questions which the vision raises bear on matters of angelology, as to which all is purposely left vague and indeterminate, or which lie in a sphere wholly beyond our cognisance.

It may first be asked whether the splendid angel of the opening vision is also the being in the similitude of a man who thrice touches, encourages, and strengthens Daniel. It is perhaps simplest to suppose that this is the case,659 and that the Great Prince tones down his overpowering glory to more familiar human semblance in order to dispel the terrors of the seer.

The general conception of the archangels as princes of the nations, and as contending with each other, belongs to the later developments of Hebrew opinion on such subjects.660 Some have supposed that the "princes" of Persia and Javan to whom Gabriel and Michael are opposed are, not good angels, but demonic powers, – "the world-rulers of this darkness" – subordinate to the evil spirit whom St. Paul does not hesitate to call "the god of this world," and "the prince of the powers of the air." This is how they account for this "war in heaven," so that "the dragon and his angels" fight against "Michael and his angels." Be that as it may, this mode of presenting the guardians of the destinies of nations is one respecting which we have no further gleams of revelation to help us.

Ewald regards the two last verses of the chapter as a sort of soliloquy of the angel Gabriel with himself. He is pressed for time. His coming has already been delayed by the opposition of the guardian-power of the destinies of Persia. If Michael, the great archangel of the Hebrews, had not come to his aid, and (so to speak) for a time relieved guard, he would have been unable to come. But even the respite leaves him anxious. He seems to feel it almost necessary that he should at once return to contend against the Prince of Persia, and against a new adversary, the Prince of Javan, who is on his way to do mischief. Yet on the whole he will stay and enlighten Daniel before he takes his flight, although there is no one but Michael who aids him against these menacing princes. It is difficult to know whether this is meant to be ideal or real – whether it represents a struggle of angels against demons, or is merely meant for a sort of parable which represents the to-and-fro conflicting impulses which sway the destinies of earthly kingdoms. In any case the representation is too unique and too remote from earth to enable us to understand its spiritual meaning, beyond the bare indication that God sitteth above the water-floods and God remaineth a king for ever. It is another way of showing us that the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing; that the kings of the earth set themselves and the rulers take counsel together; but that they can only accomplish what God's hand and God's counsel have predetermined to be done; and that when they attempt to overthrow the destinies which God has foreordained, "He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh them to scorn, the Lord shall have them in derision." These, apart from all complications or developments of angelology or demonology, are the continuous lesson of the Word of God, and are confirmed by all that we decipher of His providence in His ways of dealing with nations and with men.

CHAPTER V

AN ENIGMATIC PROPHECY PASSING INTO DETAILS OF THE REIGN OF ANTIOCHUS EPIPHANES

"Pone hæc dici de Antiocho, quid nocet religioni nostræ?" – Hieron. ed. Vallars, v. 722.

If this chapter were indeed the utterance of a prophet in the Babylonian Exile, nearly four hundred years before the events – events of which many are of small comparative importance in the world's history – which are here so enigmatically and yet so minutely depicted, the revelation would be the most unique and perplexing in the whole Scriptures. It would represent a sudden and total departure from every method of God's providence and of God's manifestation of His will to the minds of the prophets. It would stand absolutely and abnormally alone as an abandonment of the limitations of all else which has ever been foretold. And it would then be still more surprising that such a reversal of the entire economy of prophecy should not only be so widely separated in tone from the high moral and spiritual lessons which it was the special glory of prophecy to inculcate, but should come to us entirely devoid of those decisive credentials which could alone suffice to command our conviction of its genuineness and authenticity. "We find in this chapter," says Mr. Bevan, "a complete survey of the history from the beginning of the Persian period down to the time of the author. Here, even more than in the earlier vision, we are able to perceive how the account gradually becomes more definite as it approaches the latter part of the reign of Antiochus Epiphanes, and how it then passes suddenly from the domain of historical facts to that of ideal expectations."661 In recent days, when the force of truth has compelled so many earnest and honest thinkers to the acceptance of historic and literary criticism, the few scholars who are still able to maintain the traditional views about the Book of Daniel find themselves driven, like Zöckler and others, to admit that even if the Book of Daniel as a whole can be regarded as the production of the exiled seer five and a half centuries before Christ, yet in this chapter at any rate there must be large interpolations.662

There is here an unfortunate division of the chapters. The first verse of chap. xi. clearly belongs to the last verses of chap. x. It seems to furnish the reason why Gabriel could rely on the help of Michael, and therefore may delay for a few moments his return to the scene of conflict with the Prince of Persia and the coming King of Javan. Michael will for that brief period undertake the sole responsibility of maintaining the struggle, because Gabriel has put him under a direct obligation by special assistance which he rendered to him only a little while previously in the first year of the Median Darius.663 Now, therefore, Gabriel, though in haste, will announce to Daniel the truth.

The announcement occupies five sections.

First Section (xi. 2-9). – Events from the rise of Alexander the Great (b. c. 336) to the death of Seleucus Nicator (b. c. 280). There are to be three kings of Persia after Cyrus (who is then reigning), of whom the third is to be the richest;664 and "when he is waxed strong through his riches, he shall stir up the all665 against the realm of Javan."

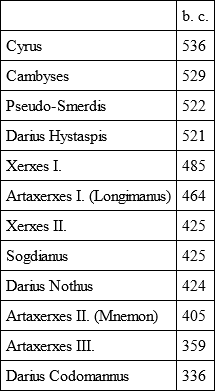

There were of course many more than four kings of Persia666: viz. —

But probably the writer had no historic sources to which to refer, and only four Persian kings are prominent in Scripture – Cyrus, Darius, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes. Darius Codomannus is indeed mentioned in Neh. xii. 22, but might have easily been overlooked, and even confounded with another Darius in uncritical and unhistorical times. The rich fourth king who "stirs up the all against the realm of Grecia" might be meant for Artaxerxes I., but more probably refers to Xerxes (Achashverosh, or Ahasuerus), and his immense and ostentatious invasion of Greece (b. c. 480). His enormous wealth is dwelt upon by Herodotus.667

Ver. 3 (b. c. 336-323). – Then shall rise a mighty king (Alexander the Great), and shall rule with great dominion, and do according to his will. "Fortunam solus omnium mortalium in potestate habuit," says his historian, Quintus Curtius.668

Ver. 4 (b. c. 323). – But when he is at the apparent zenith of his strength his kingdom shall be broken, and shall not descend to any of his posterity,669 but (b. c. 323-301) shall be for others, and shall ultimately (after the Battle of Ipsus, b. c. 301) be divided towards the four winds of heaven, into the kingdoms of Cassander (Greece and Macedonia), Ptolemy (Egypt, Cœle-Syria, and Palestine), Lysimachus (Asia Minor), and Seleucus (Upper Asia).

Ver. 5. – Of these four kingdoms and their kings the vision is only concerned with two – the kings of the South670 (i. e., the Lagidæ, or Egyptian Ptolemies, who sprang from Ptolemy Lagos), and the kings of the North (i. e., the Antiochian Seleucidæ). They alone are singled out because the Holy Land became a sphere of contentions between these rival dynasties.671

b. c. 306. – The King of the South (Ptolemy Soter, son of Lagos) shall be strong, and shall ultimately assume the title of Ptolemy I., King of Egypt.

But one of his princes or generals (Seleucus Nicator) shall be stronger,672 and, asserting his independence, shall establish a great dominion over Northern Syria and Babylonia.

Ver. 6 (b. c. 250). – The vision then passes over the reign of Antiochus II. (Soter), and proceeds to say that "at the end of years" (i. e., some half-century later, b. c. 250) the kings of the North and South should form a matrimonial alliance. The daughter of the King of the South – the Egyptian Princess Berenice, daughter of Ptolemy II. (Philadelphus), should come to the King of the North (Antiochus Theos) to make an agreement. This agreement (marg., "equitable conditions") was that Antiochus Theos should divorce his wife and half-sister Laodice, and disinherit her children, and bequeath the throne to any future child of Berenice, who would thus unite the empires of the Ptolemies and the Seleucidæ.673 Berenice took with her so vast a dowry that she was called "the dowry-bringer" (φερνόφορος).674 Antiochus himself accompanied her as far as Pelusium (b. c. 247). But the compact ended in nothing but calamity. For, two years after, Ptolemy II. died, leaving an infant child by Berenice. But Berenice did "not retain the strength of her arm,"675 since the military force which accompanied her proved powerless for her protection; nor did Ptolemy II. abide, nor any support which he could render. On the contrary, there was overwhelming disaster. Berenice's escort, her father, her husband, all perished, and she herself and her infant child were murdered by her rival, Laodice (b. c. 246), in the sanctuary of Daphne, whither she had fled for refuge.

Ver. 7 (b. c. 285-247). – But the murder of Berenice shall be well avenged. For "out of a shoot from her roots" stood up one in his office, even her brother Ptolemy III. (Euergetes), who, unlike the effeminate Ptolemy II., did not entrust his wars to his generals, but came himself to his army. He shall completely conquer the King of the North (Seleucus II., Kallinikos, son of Antiochus Theos and Laodice), shall seize his fortress (Seleucia, the port of Antioch).676

Ver. 8 (b. c. 247). – In this campaign Ptolemy Euergetes, who earned the title of "Benefactor" by this vigorous invasion, shall not only win immense booty – four thousand talents of gold and many jewels, and forty thousand talents of silver – but shall also carry back with him to Egypt the two thousand five hundred molten images,677 and idolatrous vessels, which, two hundred and eighty years before (b. c. 527), Cambyses had carried away from Egypt.678

After this success he will, for some years, refrain from attacking the Seleucid kings.679

Ver. 9 (b. c. 240). – Seleucus Kallinikos makes an attempt to avenge the shame and loss of the invasion of Syria by invading Egypt, but he returns to his own land totally foiled and defeated, for his fleet was destroyed by a storm.680

Second Section (vv. 10-19). – Events from the death of Ptolemy Euergetes (b. c. 247) to the death of Antiochus III. (the Great, b. c. 175). In the following verses, as Behrmann observes, there is a sort of dance of shadows, only fully intelligible to the initiated.

Ver. 10. – The sons of Seleucus Kallinikos were Seleucus III. (Keraunos, b. c. 227-224) and Antiochus the Great (b. c. 224-187). Keraunos only reigned two years, and in b. c. 224 his brother Antiochus III. succeeded him. Both kings assembled immense forces to avenge the insult of the Egyptian invasion, the defeat of their father, and the retention of their port and fortress of Seleucia. It was only sixteen miles from Antioch, and being still garrisoned by Egyptians, constituted a standing danger and insult to their capital city.

Ver. 11. – After twenty-seven years the port of Seleucia is wrested from the Egyptians by Antiochus the Great, and he so completely reverses the former successes of the King of the South as to conquer Syria as far as Gaza.

Ver. 12 (b. c. 217). – But at last the young Egyptian King, Ptolemy IV. (Philopator), is roused from his dissipation and effeminacy, advances to Raphia (southwest of Gaza) with a great army of twenty thousand foot, five thousand horse, and seventy-three elephants, and there, to his own immense self-exaltation, he inflicts a severe defeat on Antiochus, and "casts down tens of thousands."681 Yet the victory is illusive, although it enables Ptolemy to annex Palestine to Egypt. For Ptolemy "shall not show himself strong," but shall, by his supineness, and by making a speedy peace, throw away all the fruits of his victory, while he returns to his past dissipation (b. c. 217-204).682

Ver. 13. – Twelve years later (b. c. 205) Ptolemy Philopator died, leaving an infant son, Ptolemy Epiphanes. Antiochus, smarting from his defeat at Raphia, again assembled an army which was still greater than before (b. c. 203), and much war-material. In the intervening years he had won great victories in the East as far as India.

Ver. 14. – Antiochus shall be aided by the fact that many – including his ally Philip, King of Macedon, and various rebel-subjects of Ptolemy Epiphanes – stood up against the King of Egypt and wrested Phœnicia and Southern Syria from him. The Syrians were further strengthened by the assistance of the "children of the violent" among the Jews, "who shall lift themselves up to fulfil the vision of the oracle;683 but they shall fall." We read in Josephus that many of the Jews helped Antiochus;684 but the allusion to "the vision" is entirely obscure. Ewald supposes a reference to some prophecy no longer extant. Dr. Joël thinks that the Hellenising Jews may have referred to Isa. xix. in favour of the plans of Antiochus against Egypt.

Vv. 15, 16. – But however much any of the Jews may have helped Antiochus under the hope of ultimately regaining their independence, their hopes were frustrated. The Syrian King came, besieged, and took a well-fenced city – perhaps an allusion to the fact that he wrested Sidon from the Egyptians. After his great victory over the Egyptian general Scopas at Mount Panium (b. c. 198), the routed Egyptian forces, to the number of ten thousand, flung themselves into that city.685 This campaign ruined the interests of Egypt in Palestine, "the glorious land."686 Palestine now passed to Antiochus, who took possession "with destruction in his hand."

Ver. 17 (b. c. 198-195). – After this there shall again be an attempt at "equitable negotiations"; by which, however, Antiochus hoped to get final possession of Egypt and destroy it. He arranged a marriage between "a daughter of women" – his daughter Cleopatra – and Ptolemy Epiphanes. But this attempt also entirely failed.

Ver. 18 (b. c. 190). – Antiochus therefore "sets his face in another direction," and tries to conquer the islands and coasts of Asia Minor. But a captain – the Roman general, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus – puts an end to the insolent scorn with which he had spoken of the Romans, and pays him back with equal scorn,687 utterly defeating him in the great Battle of Magnesia (b. c. 190), and forcing him to ignominious terms.

Ver. 19 (b. c. 175). – Antiochus next turns his attention ("sets his face") to strengthen the fortresses of his own land in the east and west; but making an attempt to recruit his dissipated wealth by the plunder of the Temple of Belus in Elymais, "stumbles and falls, and is not found."

Third Section (vv. 20-27). – Events under Seleucus Philopator down to the first attempts of Antiochus Epiphanes against Egypt (b. c. 170).

Ver. 20. – Seleucus Philopator (b. c. 187-176) had a character the reverse of his father's. He was no restless seeker for glory, but desired wealth and quietness.688 Among the Jews, however, he had a very evil reputation, for he sent an exactor– a mere tax-collector, Heliodorus – "to pass through the glory of the kingdom."689 He only reigned twelve years, and then was "broken" —i. e., murdered by Heliodorus, neither in anger nor in battle, but by poison administered by this "tax-collector." The versions all vary, but I feel little doubt that Dr. Joël is right when he sees in the curious phrase nogesh heder malkooth, "one that shall cause a raiser of taxes to pass over the kingdom" – of which neither Theodotion nor the Vulgate can make anything – a cryptographic allusion to the name Heliodorus;690 and possibly the predicted fate may (by a change of subject) also refer to the fact that Heliodorus was checked, not by force, but by the vision in the Temple (2 Macc. v. 18, iii. 24-29). We find from 2 Macc. iv. 1 that Simeon, the governor of the Temple, charged Onias with a trick to terrify Heliodorus. This is a very probable view of what occurred.691

Ver. 21. – Seleucus Philopator died b. c. 175 without an heir. This made room for a contemptible person, a reprobate, who had no real claim to royal dignity,692 being only a younger son of Antiochus the Great. He came by surprise, "in time of security," and obtained the kingdom by flatteries.693

Ver. 22. – Yet "the overflowing wings of Egypt" (or "the arms of a flood") "were swept away before him and broken; yea, and even a covenanted or allied prince." Some explain this of his nephew Ptolemy Philometor, others of Onias III., "the prince of the covenant" —i. e., the princely high priest, whom Antiochus displaced in favour of his brother, the apostate Joshua, who Græcised his name into Jason, as his brother Onias did in calling himself Menelaus.694

Ver. 23. – This mean king should prosper by deceit which he practised on all connected with him;695 and though at first he had but few adherents, he should creep into power.

Ver. 24. – "In time of security shall he come, even upon the fattest places of the province." By this may be meant his invasions of Galilee and Lower Egypt. Acting unlike any of his royal predecessors, he shall lavishly scatter his gains and his booty among needy followers,696 and shall plot to seize Pelusium, Naucratis, Alexandria, and other strongholds of Egypt for a time.

Ver. 25. – After this (b. c. 171) he shall, with a "great army," seriously undertake his first invasion of Egypt, and shall be met by his nephew Ptolemy Philometor with another immense army. In spite of this, the young Egyptian King shall fail through the treachery of his own courtiers. He shall be outwitted and treacherously undermined by his uncle Antiochus. Yes! even while his army is fighting, and many are being slain, the very men who "eat of his dainties," even his favourite and trusted courtiers Eulæus and Lenæus, will be devising his ruin, and his army shall be swept away.

Vv. 26, 27 (b. c. 174). – The Syrians and the Egyptian King, nephew and uncle, shall in nominal amity sit at one banquet, eating from one table;697 but all the while they will be distrustfully plotting against each other and "speaking lies" to each other. Antiochus will pretend to ally himself with the young Philometor against his brother Ptolemy Euergetes II. – generally known by his derisive nickname as Ptolemy Physkon698– whom after eleven months the Alexandrians had proclaimed king. But all these plots and counter-plots should be of none effect, for the end was not yet.

Fourth Section (vv. 28-35). – Events between the first attack of Antiochus on Jerusalem (b. c. 170) and his plunder of the Temple to the first revolt of the Maccabees (b. c. 167).

Ver. 28 (b. c. 168). – Returning from Egypt with great plunder, Antiochus shall set himself against the Holy Covenant. He put down the usurping high priest Jason, who, with much slaughter, had driven out his rival usurper and brother, Menelaus. He massacred many Jews, and returned to Antioch enriched with golden vessels seized from the Temple.699

Ver. 29. – In b. c. 168 Antiochus again invaded Egypt, but with none of the former splendid results. For Ptolemy Philometor and Physkon had joined in sending an embassy to Rome to ask for help and protection. In consequence of this, "ships from Kittim"700– namely, the Roman fleet – came against him, bringing the Roman commissioner, Gaius Popilius Lænas. When Popilius met Antiochus, the king put out his hand to embrace him; but the Roman merely held out his tablets, and bade Antiochus read the Roman demand that he and his army should at once evacuate Egypt. "I will consult my friends on the subject," said Antiochus. Popilius, with infinite haughtiness and audacity, simply drew a circle in the sand with his vine-stick round the spot on which the king stood, and said, "You must decide before you step out of that circle." Antiochus stood amazed and humiliated; but seeing that there was no help for it, promised in despair to do all that the Romans demanded.701

Ver. 30. – Returning from Egypt in an indignant frame of mind, he turned his exasperation against the Jews and the Holy Covenant, especially extending his approval to those who apostatised from it.

Ver. 31. – Then (b. c. 168) shall come the climax of horror. Antiochus shall send troops to the Holy Land, who shall desecrate the sanctuary and fortress of the Temple, and abolish the daily sacrifice (Kisleu 15), and set up the abomination that maketh desolate.702

Ver. 32. – To carry out these ends the better, and with the express purpose of putting an end to the Jewish religion, he shall pervert or "make profane" by flatteries the renegades who are ready to apostatise from the faith of their fathers. But there shall be a faithful remnant who will bravely resist him to the uttermost. "The people who know their God will be valiant, and do great deeds."

Ver. 33. – To keep alive the national faith "wise teachers of the people shall instruct many," and will draw upon their own heads the fury of persecution, so that many shall fall by sword, and by flame, and by captivity, and by spoliation for many days.

Ver. 34. – But in the midst of this fierce onslaught of cruelty they shall be "holpen with a little help." There shall arise the sect of the Chasidîm, or "the Pious," bound together by Tugendbund to maintain the Laws which Israel received from Moses of old.703 These good and faithful champions of a righteous cause will indeed be weakened by the false adherence of waverers and flatterers.

Ver. 35. – To purge the party from such spies and Laodiceans, the teachers, like the aged priest Mattathias at Modin, and the aged scribe Eleazar, will have to brave even martyrdom itself till the time of the end.

Fifth Section (vv. 36-45, b. c. 147-164). – Events from the beginning of the Maccabean rising to the death of Antiochus Epiphanes.

Ver. 36. – Antiochus will grow more arbitrary, more insolent, more blasphemous, from day to day, calling himself "God" (Theos) on his coins, and requiring all his subjects to be of his religion,704 and so even more kindling against himself the wrath of the God of gods by his monstrous utterances, until the final doom has fallen.

Ver. 37. – He will, in fact, make himself his own god, paying no regard (by comparison) to his national or local god, the Olympian Zeus, nor to the Syrian deity, Tammuz-Adonis, "the desire of women."705