полная версия

полная версияThe Expositor's Bible: The Book of Daniel

In his appeal for the interpretation of this symbol there are fresh particulars about this horn which had eyes and spake very great things. We are told that "his look was more stout than his fellows"; and that "he made war against the saints and prevailed against them, until the Ancient of Days came. Then judgment was given to the saints, and the time came that the saints possessed the kingdom."

The interpretation is that the fourth beast is an earth-devouring, trampling, shattering kingdom, diverse from all kingdoms; its ten horns are ten kings that shall arise from it.493 Then another king shall arise, diverse from the first, who shall subdue three kings, shall speak blasphemies, shall wear out the saints, and will strive to change times and laws. But after "a time, two times, and a half,"494 the judgment shall sit, and he will be annihilated, and his dominion shall be given for ever to the people of the saints of the Most High.

Such was the vision; such its interpretation; and there can be no difficulty as to its general significance.

I. That the four empires, and their founders, are not identical with the four empires of the metal colossus in Nebuchadrezzar's dream, is an inference which, apart from dogmatic bias, would scarcely have occurred to any unsophisticated reader. To the imagination of Nebuchadrezzar, the heathen potentate, they would naturally present themselves in their strength and towering grandeur, splendid and impassive and secure, till the mysterious destruction smites them. To the Jewish seer they present themselves in their cruel ferocity and headstrong ambition as destroying wild beasts. The symbolism would naturally occur to all who were familiar with the winged bulls and lions and other gigantic representations of monsters which decorated the palace-walls of Nineveh and Babylon. Indeed, similar imagery had already found a place on the prophetic page.495

II. The turbulent sea, from which the immense beasts emerge after the struggling of the four winds of heaven upon its surface, is the sea of nations.496

III. The first great beast is Nebuchadrezzar and the Babylonian Empire.497 There is nothing strange in the fact that there should be a certain transfusion or overlapping of the symbols, the object not being literary congruity, but the creation of a general impression. He is represented as a lion, because lions were prevalent in Babylonia, and were specially prominent in Babylonian decorations. His eagle-wings symbolise rapacity and swiftness.498 But, according to the narrative already given, a change had come over the spirit of Nebuchadrezzar in his latter days. That subduing and softening by the influence of a Divine power is represented by the plucking off of the lion's eagle-wings, and its fall to earth. But it was not left to lie there in impotent degradation. It is lifted up from the earth, and humanised, and made to stand on its feet as a man, and a man's heart is given to it.499

IV. The bear, which places itself upon one side, is the Median Empire, smaller than the Chaldean, as the bear is smaller and less formidable than the lion. The crouching on one side is obscure. It is explained by some as implying that it was lower in exaltation than the Babylonian Empire; by others that "it gravitated, as regards its power, only towards the countries west of the Tigris and Euphrates."500 The meaning of the "three ribs in its mouth" is also uncertain. Some regard the number three as a vague round number; others refer it to the three countries over which the Median dominion extended – Babylonia, Assyria, and Syria; others, less probably, to the three chief cities. The command, "Arise, devour much flesh," refers to the prophecies of Median conquest,501 and perhaps to uncertain historical reminiscences which confused "Darius the Mede" with Darius the son of Hystaspes. Those who explain this monster as an emblem, not of the Median but of the Medo-Persian Empire, neglect the plain indications of the Book itself, for the author regards the Median and Persian Empires as distinct.502

V. The leopard or panther represents the Persian kingdom.503 It has four wings on its back, to indicate how freely and swiftly it soared to the four quarters of the world. Its four heads indicate four kings. There were indeed twelve or thirteen kings of Persia between b. c. 536 and b. c. 333; but the author of the Book of Daniel, who of course had no books of history before him, only thinks of the four who were most prominent in popular tradition – namely (as it would seem), Cyrus, Darius, Artaxerxes, and Xerxes.504 These are the only four names which the writer knew, because they are the only ones which occur in Scripture. It is true that the Darius of Neh. xii. 22 is not the Great Darius, son of Hystaspes, but Darius Codomannus (b. c. 424-404). But this fact may most easily have been overlooked in uncritical and unhistoric times. And "power was given to it," for it was far stronger than the preceding kingdom of the Medes.

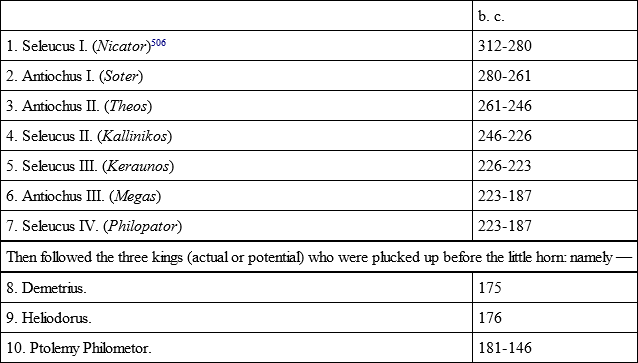

VI. The fourth monster won its chief aspect of terribleness from the conquests of Alexander, which blazed over the East with such irresistible force and suddenness.505 The great Macedonian, after his massacres at Tyre, struck into the Eastern world the intense feeling of terror which we still can recognise in the narrative of Josephus. His rule is therefore symbolised by a monster diverse from all the beasts before it in its sudden leap out of obscurity, in the lightning-like rapidity of its flash from West to East, and in its instantaneous disintegration into four separate kingdoms. It is with one only of those four kingdoms of the Diadochi, the one which so terribly affected the fortunes of the Holy Land, that the writer is predominantly concerned – namely, the empire of the Seleucid kings. It is in that portion of the kingdom – namely, from the Euxine to the confines of Arabia – that the ten horns arise which, we are told, symbolise ten kings. It seems almost certain that these ten kings are intended for: —

Примечание 1506

Of these three who succumbed to the machinations of Antiochus Epiphanes, or the little horn,507 the first, Demetrius, was the only son of Seleucus Philopator, and true heir to the crown. His father sent him to Rome as a hostage, and released his brother Antiochus. So far from showing gratitude for this generosity, Antiochus, on the murder of Seleucus IV. (b. c. 175), usurped the rights of his nephew (Dan. xi. 21).

The second, Heliodorus, seeing that Demetrius the heir was out of the way, poisoned Seleucus Philopator, and himself usurped the kingdom.508

Ptolemy Philometor was the son of Cleopatra, the sister of Seleucus Philopator. A large party was in favour of uniting Egypt and Persia under his rule. But Antiochus Epiphanes ignored the compact which had made Cœle-Syria and Phœnicia the dower of Cleopatra, and not only kept Philometor from his rights, but would have deprived him of Egypt also but for the strenuous interposition of the Romans and their ambassador M. Popilius Lænas.509

When the three horns had thus fallen before him, the little horn – Antiochus Epiphanes – sprang into prominence. The mention of his "eyes" seems to be a reference to his shrewdness, cunning, and vigilance.510 The "mouth that spoke very great things"511 alludes to the boastful arrogance which led him to assume the title of Epiphanes, or "the illustrious" – which his scornful subjects changed into Epimanes, "the mad" – and to his assumption even of the title Theos, "the god," on some of his coins.512 His look "was bigger than his fellows," for he inspired the kings of Egypt and other countries with terror. "He made war against the saints," with the aid of "Jason and Menelaus, those ungodly wretches," and "prevailed against them." He "wore out the saints of the Most High," for he took Jerusalem by storm, plundered it, slew eighty thousand men, women, and children, took forty thousand prisoners, and sold as many into slavery (b. c. 170).513 "As he entered the sanctuary to plunder it, under the guidance of the apostate high priest Menelaus, he uttered words of blasphemy, and he carried off all the gold and silver he could find, including the golden table, altar of incense, candlesticks, and vessels, and even rifled the subterraneous vaults, so that he seized no less than eighteen hundred talents of gold."514 He then sacrificed swine upon the altar, and sprinkled the whole Temple with the broth.

Further than all this, "he thought to change times and laws"; and they were "given into his hand until a time, and two times, and a half." For he made a determined attempt to put down the Jewish feasts, the Sabbath, circumcision, and all the most distinctive Jewish ordinances.515 In b. c. 167, two years after his cruel devastation of the city, he sent Apollonius, his chief collector of tribute, against Jerusalem, with an army of twenty-two thousand men. On the first Sabbath after his arrival, Apollonius sent his soldiers to massacre all the men whom they met in the streets, and to seize the women and children as slaves. He occupied the castle on Mount Zion, and prevented the Jews from attending the public ordinances of their sanctuary. Hence in June b. c. 167 the daily sacrifice ceased, and the Jews fled for their lives from the Holy City. Antiochus then published an edict forbidding all his subjects in Syria and elsewhere – even the Zoroastrians in Armenia and Persia – to worship any gods, or acknowledge any religion but his.516 The Jewish sacred books were burnt, and not only the Samaritans but many Jews apostatised, while others hid themselves in mountains and deserts.517 He sent an old philosopher named Athenæus to instruct the Jews in the Greek religion, and to enforce its observance. He dedicated the Temple to Zeus Olympios, and built on the altar of Jehovah a smaller altar for sacrifice to Zeus, to whom he must also have erected a statue. This heathen altar was set up on Kisleu (December) 15, and the heathen sacrifice began on Kisleu 25. All observance of the Jewish Law was now treated as a capital crime. The Jews were forced to sacrifice in heathen groves at heathen altars, and to walk, crowned with ivy, in Bacchic processions. Two women who had braved the despot's wrath by circumcising their children were flung from the Temple battlements into the vale below.518

The triumph of this blasphemous and despotic savagery was arrested, first by the irresistible force of determined martyrdom which preferred death to unfaithfulness, and next by the armed resistance evoked by the heroism of Mattathias, the priest at Modin. When Apelles visited the town, and ordered the Jews to sacrifice, Mattathias struck down with his own hand a Jew who was preparing to obey. Then, aided by his strong heroic sons, he attacked Apelles, slew him and his soldiers, tore down the idolatrous altar, and with his sons and adherents fled into the wilderness, where they were joined by many of the Jews.

The news of this revolt brought Antiochus to Palestine in b. c. 166, and among his other atrocities he ordered the execution by torture of the venerable scribe Eleazar, and of the pious mother with her seven sons. In spite of all his efforts the party of the Chasidîm grew in numbers and in strength. When Mattathias died, Judas the Maccabee became their leader, and his brother Simon their counsellor.519 While Antiochus was celebrating his mad and licentious festival at Daphne, Judas inflicted a severe defeat on Apollonius, and won other battles, which made Antiochus vow in an access of fury that he would exterminate the nation (Dan. xi. 44). But he found himself bankrupt, and the Persians and Armenians were revolting from him in disgust. He therefore sent Lysias as his general to Judæa, and Lysias assembled an immense army of forty thousand foot and seven thousand horse, to whom Judas could only oppose six thousand men.520 Lysias pitched his camp at Beth-shur, south of Jerusalem. There Judas attacked him with irresistible valour and confidence, slew five thousand of his soldiers, and drove the rest to flight.

Lysias retired to Antioch, intending to renew the invasion next year. Thereupon Judas and his army recaptured Jerusalem, and restored and cleansed and reconsecrated the dilapidated and desecrated sanctuary. He made a new shewbread-table, incense-altar, and candlestick of gold in place of those which Antiochus had carried off, and new vessels of gold, and a new veil before the Holiest Place. All this was completed on Kisleu 25, b. c. 165, about the time of the winter solstice, "on the same day of the year on which, three years before, it had been profaned by Antiochus, and just three years and a half – 'a time, two times, and half a time' – after the city and Temple had been desolated by Apollonius."521 They began the day by renewing the sacrifices, kindling the altar and the candlestick by pure fire struck by flints. The whole law of the Temple service continued thenceforward without interruption till the destruction of the Temple by the Romans. It was a feast in commemoration of this dedication – called the Encænia and "the Lights" – which Christ honoured by His presence at Jerusalem.522

The neighbouring nations, when they heard of this revolt of the Jews, and its splendid success, proposed to join with Antiochus for their extermination. But meanwhile the king, having been shamefully repulsed in his sacrilegious attack on the Temple of Artemis at Elymais, retired in deep chagrin to Ecbatana, in Media. It was there that he heard of the Jewish successes and set out to chastise the rebels. On his way he heard of the recovery of Jerusalem, the destruction of his heathen altars, and the purification of the Temple. The news flung him into one of those paroxysms of fury to which he was liable, and, breathing out threatenings and slaughter, he declared that he would turn Jerusalem into one vast cemetery for the whole Jewish race. Suddenly smitten with a violent internal malady, he would not stay his course, but still urged his charioteer to the utmost speed.523 In consequence of this the chariot was overturned, and he was flung violently to the ground, receiving severe injuries. He was placed in a litter, but, unable to bear the agonies caused by its motion, he stopped at Tabæ, in the mountains of Parætacene, on the borders of Persia and Babylonia, where he died, b. c. 164, in very evil case, half mad with the furies of a remorseful conscience.524 The Jewish historians say that, before his death, he repented, acknowledged the crimes he had committed against the Jews, and vowed that he would repair them if he survived. The stories of his death resemble those of the deaths of Herod, of Galerius, of Philip II., and of other bitter persecutors of the saints of God. Judas the Maccabee, who had overthrown his power in Palestine, died at Eleasa in b. c. 161, after a series of brilliant victories.

Such were the fortunes of the king whom the writer shadows forth under the emblem of the little horn with human eyes and a mouth which spake blasphemies, whose power was to be made transitory, and to be annihilated and destroyed unto the end.525 And when this wild beast was slain, and its body given to the burning fire, the rest of the beasts were indeed to be deprived of their splendid dominions, but a respite of life is given them, and they are suffered to endure for a time and a period.526

But the eternal life, and the imperishable dominion, which were denied to them, are given to another in the epiphany of the Ancient of Days. The vision of the seer is one of a great scene of judgment. Thrones are set for the heavenly assessors, and the Almighty appears in snow-white raiment, and on His chariot-throne of burning flame which flashes round Him like a vast photosphere.527 The books of everlasting record are opened before the glittering faces of the myriads of saints who accompany Him, and the fiery doom is passed on the monstrous world-powers who would fain usurp His authority.528

But who is the "one even as a son of man," who "comes with the clouds of heaven," and who "is brought before the Ancient of Days,"529 to whom is given the imperishable dominion? That he is not an angel appears from the fact that he seems to be separate from all the ten thousand times ten thousand who stand around the cherubic chariot. He is not a man, but something more. In this respect he resembles the angels described in Dan. viii. 15, x. 16-18. He has "the appearance of a man," and is "like the similitude of the sons of men."530

We should naturally answer, in accordance with the multitude of ancient and modern commentators both Jewish and Christian, that the Messiah is intended;531 and, indeed, our Lord alludes to the prophecy in Matt. xxvi. 64. That the vision is meant to indicate the establishment of the Messianic theocracy cannot be doubted. But if we follow the interpretation given by the angel himself in answer to Daniel's entreaty, the personality of the Messiah seems to be at least somewhat subordinate or indistinct. For the interpretation, without mentioning any person, seems to point only to the saints of Israel who are to inherit and maintain that Divine kingdom which has been already thrice asserted and prophesied. It is the "holy ones" (Qaddîshîn), "the holy ones of the Most High" (Qaddîshî Elîonîn), upon whom the never-ending sovereignty is conferred;532 and who these are cannot be misunderstood, for they are the very same as those against whom the little horn has been engaged in war.533 The Messianic kingdom is here predominantly represented as the spiritual supremacy of the chosen people. Neither here, nor in ii. 44, nor in xii. 3, does the writer separately indicate any Davidic king, or priest upon his throne, as had been already done by so many previous prophets.534 This vision does not seem to have brought into prominence the rule of any Divinely Incarnate Christ over the kingdom of the Highest. In this respect the interpretation of the "one even as a son of man" comes upon us as a surprise, and seems to indicate that the true interpretation of that element of the vision is that the kingdom of the saints is there personified; so that as wild beasts were appropriate emblems of the world-powers, the reasonableness and sanctity of the saintly theocracy are indicated by a human form, which has its origin in the clouds of heaven, not in the miry and troubled sea. This is the view of the Christian father Ephræm Syrus, as well as of the Jewish exegete Abn Ezra; and it is supported by the fact that in other apocryphal books of the later epoch, as in the Assumption of Moses and the Book of Jubilees, the Messianic hope is concentrated in the conception that the holy nation is to have the dominance over the Gentiles. At any rate, it seems that, if truth is to guide us rather than theological prepossession, we must take the significance of the writer, not from the emblems of the vision, but from the divinely imparted interpretation of it; and there the figure of "one as a son of man" is persistently (vv. 18, 22, 27) explained to stand, not for the Christ Himself, but for "the holy ones of the Most High,"535 whose dominion Christ's coming should inaugurate and secure.

The chapter closes with the words: "Here is the end of the matter. As for me, Daniel, my thoughts much troubled me, and my brightness was changed in me: but I kept the matter in my heart."

CHAPTER II

THE RAM AND THE HE-GOAT

This vision is dated as having occurred in the third year of Belshazzar; but it is not easy to see the significance of the date, since it is almost exclusively occupied with the establishment of the Greek Empire, its dissolution into the kingdoms of the Diadochi, and the godless despotism of King Antiochus Epiphanes.

The seer imagines himself to be in the palace of Shushan: "As I beheld I was in the castle of Shushan."536 It has been supposed by some that Daniel was really there upon some business connected with the kingdom of Babylon. But this view creates a needless difficulty. Shushan, which the Greeks called Susa, and the Persians Shush (now Shushter), "the city of the lily," was "the palace" or fortress (bîrah537) of the Achæmenid kings of Persia, and it is most unlikely that a chief officer of the kingdom of Babylon should have been there in the third year of the imaginary King Belshazzar, just when Cyrus was on the eve of capturing Babylon without a blow. If Belshazzar is some dim reflection of the son of Nabunaid (though he never reigned), Shushan was not then subject to the King of Babylonia. But the ideal presence of the prophet there, in vision, is analogous to the presence of the exile Ezekiel in Jerusalem (Ezek. xl. 1); and these transferences of the prophets to the scenes of their operation were sometimes even regarded as bodily, as in the legend of Habakkuk taken to the lions' den to support Daniel.

Shushan is described as being in the province of Elam or Elymais, which may be here used as a general designation of the district in which Susiana was included. The prophet imagines himself as standing by the river-basin (oobâl538) of the Ulai, which shows that we must take the words "in the castle of Shushan" in an ideal sense; for, as Ewald says, "it is only in a dream that images and places are changed so rapidly." The Ulai is the river called by the Greeks the Eulæus, now the Karûn.539

Shushan is said by Pliny and Arrian to have been on the river Eulæus, and by Herodotus to have been on the banks of

"Choaspes, amber stream,

The drink of none but kings."

It seems now to have been proved that the Ulai was merely a branch of the Choaspes or Kerkhah.540

Lifting up his eyes, Daniel sees a ram standing eastward of the river-basin. It has two lofty horns, the loftier of the two being the later in origin. It butts westward, northward, and southward, and does great things.541 But in the midst of its successes a he-goat, with a conspicuous horn between its eyes,542 comes from the West so swiftly over the face of all the earth that it scarcely seems even to touch the ground,543 and runs upon the ram in the fury of his strength,544 conquering and trampling upon him, and smashing in pieces his two horns. But his impetuosity was short-lived, for the great horn was speedily broken, and four others545 rose in its place towards the four winds of heaven. Out of these four horns shot up a puny horn,546 which grew exceedingly great towards the South, and towards the East, and towards "the Glory" —i. e., towards the Holy Land.547 It became great even to the host of heaven, and cast down some of the host and of the stars to the ground, and trampled on them.548 He even behaved proudly against the prince of the host, took away from him549 "the daily" (sacrifice), polluted the dismantled sanctuary with sacrilegious arms,550 and cast the truth to the ground and prospered. Then "one holy one called to another and asked, For how long is the vision of the daily [sacrifice], and the horrible sacrilege, that thus both the sanctuary and host are surrendered to be trampled underfoot?"551 And the answer is, "Until two thousand three hundred 'erebh-bôqer, 'evening-morning'; then will the sanctuary be justified."

Daniel sought to understand the vision, and immediately there stood before him one in the semblance of a man, and he hears the distant voice of some one552 standing between the Ulai —i. e., between its two banks,553 or perhaps between its two branches, the Eulæus and the Choaspes – who called aloud to "Gabriel." The archangel Gabriel is here first mentioned in Scripture.554 "Gabriel," cried the voice, "explain to him what he has seen." So Gabriel came and stood beside him; but he was terrified, and fell on his face. "Observe, thou son of man,"555 said the angel to him; "for unto the time of the end is the vision." But since Daniel still lay prostrate on his face, and sank into a swoon, the angel touched him, and raised him up, and said that the great wrath was only for a fixed time, and he would tell him what would happen at the end of it.

The two-horned ram, he said, the Baal-keranaîm, or "lord of two horns," represents the King of Media and Persia; the shaggy goat is the Empire of Greece; and the great horn is its first king – Alexander the Great.556

The four horns rising out of the broken great horn are four inferior kingdoms. In one of these, sacrilege would culminate in the person of a king of bold face,557 and skilled in cunning, who would become powerful, though not by his own strength.558 He would prosper and destroy mighty men and the people of the holy ones,559 and deceit would succeed by his double-dealing. He would contend against the Prince of princes,560 and yet without a hand would he be broken in pieces.