полная версия

полная версияThe Expositor's Bible: The Book of Daniel

Beyond this superb edifice, where now the hyæna prowls amid miles of débris and mounds of ruin, and where the bittern builds amid pools of water, lay the unequalled city. Its walls were three hundred and eighty feet high and eighty-five feet thick, and each side of the quadrilateral they enclosed was fifteen miles in length. The mighty Euphrates flowed through the midst of the city, which is said to have covered a space of two hundred square miles; and on its farther bank, terrace above terrace, up to its central altar, rose the huge Temple of Bel, with all its dependent temples and palaces.406 The vast circuit of the walls enclosed no mere wilderness of houses, but there were interspaces of gardens, and palm-groves, and orchards, and cornland, sufficient to maintain the whole population. Here and there rose the temples reared to Nebo, and Sin the moon-god, and Mylitta, and Nana, and Samas, and other deities; and there were aqueducts or conduits for water, and forts and palaces; and the walls were pierced with a hundred brazen gates. When Milton wanted to find some parallel to the city of Pandemonium in Paradise Lost, he could only say, —

"Not Babylon,Nor great Alcairo such magnificenceEquall'd in all their glories, to enshrineBelus or Serapis their gods, or seatTheir kings, when Egypt with Assyria stroveIn wealth and luxury."Babylon, to use the phrase of Aristotle, included, not a city, but a nation.407

Enchanted by the glorious spectacle of this house of his royalty and abode of his majesty, the despot exclaimed almost in the words of some of his own inscriptions, "Is not this great Babylon that I have built for the house of the kingdom by the might of my treasures and for the honour of my majesty?"

The Bible always represents to us that pride and arrogant self-confidence are an offence against God. The doom fell on Nebuchadrezzar "while the haughty boast was still in the king's mouth." The suddenness of the Nemesis of pride is closely paralleled by the scene in the Acts of the Apostles in which Herod Agrippa I. is represented as entering the theatre at Cæsarea to receive the deputies of Tyre and Sidon. He was clad, says Josephus, in a robe of intertissued silver, and when the sun shone upon it he was surrounded with a blaze of splendour. Struck by the scene, the people, when he had ended his harangue to them, shouted, "It is the voice of a god, and not of a man!" Herod, too, in the story of Josephus, had received, just before, an ominous warning; but it came to him in vain. He accepted the blasphemous adulation, and immediately, smitten by the angel of God, he was eaten of worms, and in three days was dead.408

And something like this we see again and again in what the late Bishop Thirlwall called the "irony of history" – the very cases in which men seem to have been elevated to the very summit of power only to heighten the dreadful precipice over which they immediately fall. He mentions the cases of Persia, which was on the verge of ruin, when with lordly arrogance she dictated the Peace of Antalcidas; of Boniface VIII., in the Jubilee of 1300, immediately preceding his deadly overthrow; of Spain, under Philip II., struck down by the ruin of the Armada at the zenith of her wealth and pride. He might have added the instances of Ahab, Sennacherib, Nebuchadrezzar, and Herod Antipas; of Alexander the Great, dying as the fool dieth, drunken and miserable, in the supreme hour of his conquests; of Napoleon, hurled into the dust, first by the retreat from Moscow, then by the overthrow at Waterloo.

"While the word was yet in the king's mouth, there fell a voice from heaven." It was what the Talmudists alluded to so frequently as the Bath Qôl, or "daughter of a voice," which came sometimes for the consolation of suffering, sometimes for the admonition of overweening arrogance. It announced to him the fulfilment of the dream and its interpretation. As with one lightning-flash the glorious cedar was blasted, its leaves scattered, its fruits destroyed, its shelter reduced to burning and barrenness. Then somehow the man's heart was taken from him. He was driven forth to dwell among the beasts of the field, to eat grass like oxen. Taking himself for an animal in his degrading humiliation he lived in the open field. The dews of heaven fell upon him. His unkempt locks grew rough like eagles' feathers, his uncut nails like claws. In this condition he remained till "seven times" – some vague and sacred cycle of days – passed over him.

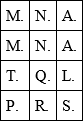

His penalty was nothing absolutely abnormal. His illness is well known to science and national tradition as that form of hypochondriasis in which a man takes himself for a wolf (lycanthropy), or a dog (kynanthropy), or some other animal.409 Probably the fifth-century monks, who were known as Boskoi, from feeding on grass, may have been, in many cases, half maniacs who in time took themselves for oxen. Cornill, so far as I know, is the first to point out the curious circumstance that a notion as to the points of analogy between Nebuchadnezzar (thus spelt) and Antiochus Epiphanes may have been strengthened by the Jewish method of mystic commentary known in the Talmud as Gematria, and in Greek as Isopsephism. That such methods, in other forms, were known and practised in early times we find from the substitution of Sheshach for Babel in Jer. xxv. 26, li. 41, and of Tabeal (by some cryptogram) for Remaliah in Isa. vii. 6; and of lebh kamai ("them that dwell in the midst of them") for Kasdîm (Chaldeans) in Jer. li. 1. These forms are only explicable by the interchange of letters known as Athbash, Albam, etc. Now Nebuchadnezzar = 423: —

נ = 50; ב = 2; ו = 6; כ = 20; ד = 4; נ = 50; א = 1;

צ = 90; ר = 200 = 423.

And Antiochus Epiphanes = 423: —

א = 1; נ = 50; ט = 9; י = 10; ו = 6; כ = 20; ו = 6;

ס = 60 =… 162}

א = 1; פ = 70; י = 10; פ = 70; נ = 50; ס = 60 = 261} = 423.

The madness of Antiochus was recognised in the popular change of his name from Epiphanes to Epimanes. But there were obvious points of resemblance between these potentates. Both of them conquered Jerusalem. Both of them robbed the Temple of its holy vessels. Both of them were liable to madness. Both of them tried to dictate the religion of their subjects.

What happened to the kingdom of Babylon during the interim is a point with which the writer does not trouble himself. It formed no part of his story or of his moral. There is, however, no difficulty in supposing that the chief mages and courtiers may have continued to rule in the king's name – a course rendered all the more easy by the extreme seclusion in which most Eastern monarchs pass their lives, often unseen by their subjects from one year's end to the other. Alike in ancient days as in modern – witness the cases of Charles VI. of France, Christian VII. of Denmark, George III. of England, and Otho of Bavaria – a king's madness is not allowed to interfere with the normal administration of the kingdom.

When the seven "times" – whether years or brief periods – were concluded, Nebuchadrezzar "lifted up his eyes to heaven," and his understanding returned to him. No further light is thrown on his recovery, which (as is not infrequently the case in madness) was as sudden as his aberration. Perhaps the calm of the infinite azure over his head flowed into his troubled soul, and reminded him that (as the inscriptions say) "the Heavens" are "the father of the gods."410 At any rate, with that upward glance came the restoration of his reason.

He instantly blessed the Most High, "and praised and honoured Him who liveth for ever, whose dominion is an everlasting dominion, and His kingdom is from generation to generation.411 And all the inhabitants of the earth are reputed as nothing; and He doeth according to His will412 in the army of heaven, and among the inhabitants of the earth;413 and none can stay His hand, or say unto Him, What doest Thou?"414

Then his lords and counsellors reinstated him in his former majesty; his honour and brightness returned to him; he was once more "that head of gold" in his kingdom.415

He concludes the story with the words: "Now I Nebuchadnezzar praise and extol and honour the King of heaven, all whose works are truth and His ways judgment;416 and those that walk in pride He is able to abase."417

He died b. c. 561, and was deified, leaving behind him an invincible name.

CHAPTER V

THE FIERY INSCRIPTION

"That night they slew him on his father's throneHe died unnoticed, and the hand unknown:Crownless and sceptreless Belshazzar lay,A robe of purple round a form of clay."Sir E. Arnold.In this chapter again we have another magnificent fresco-picture, intended, as was the last – but under circumstances of aggravated guilt and more terrible menace – to teach the lesson that "verily there is a God that judgeth the earth."

The truest way to enjoy the chapter, and to grasp the lessons which it is meant to inculcate in their proper force and vividness, is to consider it wholly apart from the difficulties as to its literal truth. To read it aright, and duly to estimate its grandeur, we must relegate to the conclusion of the story all worrying questions, impossible of final solution, as to whom the writer intended by Belshazzar, or whom by Darius the Mede.418 All such discussions are extraneous to edification, and in no way affect either the consummate skill of the picture or the eternal truths of which it is the symbolic expression. To those who, with the present writer, are convinced, by evidence from every quarter – from philology, history, the testimony of the inscriptions, and the manifold results obtained by the Higher Criticism – that the Book of Daniel is the work of some holy and highly gifted Chasîd in the days of Antiochus Epiphanes, it becomes clear that the story of Belshazzar, whatever dim fragments of Babylonian tradition it may enshrine, is really suggested by the profanity of Antiochus Epiphanes in carrying off, and doubtless subjecting to profane usage, many of the sacred vessels of the Temple of Jerusalem.419 The retribution which awaited the wayward Seleucid tyrant is prophetically intimated by the menace of doom which received such immediate fulfilment in the case of the Babylonian King. The humiliation of the guilty conqueror, "Nebuchadrezzar the Wicked," who founded the Empire of Babylon, is followed by the overthrow of his dynasty in the person of his "son," and the capture of his vast capital.

"It is natural," says Ewald, "that thus the picture drawn in this narrative should become, under the hands of our author, a true night-piece, with all the colours of the dissolute, extravagant riot of luxurious passion and growing madness, of ruinous bewilderment, and of the mysterious horror and terror of such a night of revelry and death."

The description of the scene begins with one of those crashing overtures of which the writer duly estimated the effect upon the imagination.

"Belshazzar the king made a great feast to a thousand of his lords, and drank wine before the thousand."420 The banquet may have been intended as some propitiatory feast in honour of Bel-merodach. It was celebrated in that palace which was a wonder of the world, with its winged statues and splendid spacious halls. The walls were rich with images of the Chaldeans, painted in vermilion and exceeding in dyed attire – those images of goodly youths riding on goodly horses, as in the Panathenaic procession on the frieze of the Acropolis – the frescoed pictures, on which, in the prophet's vision, Aholah and Aholibah, gloated in the chambers of secret imagery.421 Belshazzar's princes were there, and his wives, and his concubines, whose presence the Babylonian custom admitted, though the Persian regarded it as unseemly.422 The Babylonian banquets, like those of the Greeks, usually ended by a Kōmos or revelry, in which intoxication was regarded as no disgrace. Wine flowed freely. Doubtless, as in the grandiose picture of Martin, there were brasiers of precious metal, which breathed forth the fumes of incense;423 and doubtless, too, there were women and boys and girls with flutes and cymbals, to which the dancers danced in all the orgiastic abandonment of Eastern passion. All this was regarded as an element in the religious solemnity; and while the revellers drank their wine, hymns were being chanted, in which they praised "the gods of gold and of silver, of brass, of iron, of wood, and of stone." That the king drank wine before the thousand is the more remarkable because usually the kings of the East banquet in solitary state in their own apartments.424

Then the wild king, with just such a burst of folly and irreverence as characterised the banquets of Antiochus Epiphanes, bethought him of yet another element of splendour with which he might make his banquet memorable, and prove the superiority of his own victorious gods over those of other nations. The Temple of Jerusalem was famous over all the world, and there were few monarchs who had not heard of the marvels and the majesty of the God of Israel. Belshazzar, as the "son" of Nebuchadrezzar, must – if there was any historic reality in the events narrated in the previous chapter – have heard of the "signs and wonders" displayed by the King of heaven, whose unparalleled awfulness his "father" had publicly attested in edicts addressed to all the world. He must have known of the Rab-mag Daniel, whose wisdom, even as a boy, had been found superior to that of all the Chartummîm and Ashshaphîm; and how his three companions had been elevated to supreme satrapies; and how they had been delivered unsinged from the seven-times-heated furnace, whose flames had killed his father's executioners. Under no conceivable circumstances could such marvels have been forgotten; under no circumstances could they have possibly failed to create an intense and a profound impression. And Belshazzar could hardly fail to have heard of the dreams of the golden image and of the shattered cedar, and of Nebuchadrezzar's unspeakably degrading lycanthropy. His "father" had publicly acknowledged – in a decree published "to all peoples, nations, and languages that dwell in all the earth" – that humiliation had come upon him as a punishment for his overweening pride. In that same decree the mighty Nebuchadrezzar – only a year or two before, if Belshazzar succeeded him – had proclaimed his allegiance to the King of heaven; and in all previous decrees he had threatened "all people, nations, and languages" that, if they spake anything amiss against the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego, they should be cut in pieces, and their houses made a dunghill.425 Yet now Belshazzar, in the flush of pride and drunkenness,426 gives his order to insult this God with deadly impiety by publicly defiling the vessels of His awful Temple,427 at a feast in honour of his own idol deities!

Similarly Antiochus Epiphanes, if he had not been half mad, might have taken warning, before he insulted the Temple and the sacred vessels of Jerusalem, from the fact that his father, Antiochus the Great, had met his death in attempting to plunder the Temple at Elymais (b. c. 187). He might also have recalled the celebrated discomfiture – however caused – of Heliodorus in the Temple of Jerusalem.428

Such insulting and reckless blasphemy could not go unpunished. It is fitting that the Divine retribution should overtake the king on the same night, and that the same lips which thus profaned with this wine the holiest things should sip the wine of the Divine poison-cup, whose fierce heat must in the same night prove fatal to himself. But even such sinners, drinking as it were over the pit of hell, "according to a metaphor used elsewhere,429 must still at the last moment be warned by a suitable Divine sign, that it may be known whether they will honour the truth."430 Nebuchadrezzar had received his warning, and in the end it had not been wholly in vain. Even for Belshazzar it might perhaps not prove to be too late.

For at this very moment431 when the revelry was at its zenith, when the whirl of excited self-exaltation was most intense, when Judah's gold was "treading heavy on the lips" – the profane lips – of satraps and concubines, there appeared a portent, which seems at first to have been visible to the king alone.

Seated on his lofty and jewelled throne, which his eye caught something visible on the white stucco of the wall above the line of frescoes.432 He saw it over the lights which crowned the huge golden Nebrashta, or chandelier.433 The fingers of a man's hand were writing letters on the wall, and the king saw the hollow of that gigantic supernatural palm.434

"Outshone the wealth of Ormuz or of Ind,Or where the gorgeous East with richest handShowers on its kings barbaric pearl and gold,"The portent astounded and horrified him. The flush of youth and of wine faded from his cheek; – "his brightnesses were changed"; his thoughts troubled him; the bands of his loins were loosed;435 his knees smote one against another in his trembling attitude,436 as he stood arrested by the awful sight.

With a terrible cry he ordered that the whole familiar tribe of astrologers and soothsayers should be summoned. For though the hand had vanished, its trace was left on the wall of the banqueting-chamber in letters of fire. And the stricken king, anxious to know above all things the purport of that strange writing, proclaims that he who could interpret it should be clothed in scarlet, and have a chain of gold about his neck, and should be one of the triumvirs of the kingdom.437

It was the usual resource; and it failed as it had done in every previous instance. The Babylonian magi in the Book of Daniel prove themselves to be more futile even than Pharaoh's magicians with their enchantments.

The dream-interpreters in all their divisions entered the banquet-hall. The king was perturbed, the omen urgent, the reward magnificent. But it was all in vain. As usual they failed, as in every instance in which they are introduced in the Old Testament. And their failure added to the visible confusion of the king, whose livid countenance retained its pallor. The banquet, in all its royal magnificence, seemed likely to end in tumult and confusion; for the princes, and satraps, and wives, and concubines all shared in the agitation and bewilderment of their sovereign.

Meanwhile the tidings of the startling prodigy had reached the ears of the Gebîrah – the queen-mother – who, as always in the East, held a higher rank than even the reigning sultana.438 She had not been present at – perhaps had not approved of – the luxurious revel, held when the Persians were at the very gates. But now, in her young son's extremity, she comes forward to help and advise him. Entering the hall with her attendant maidens, she bids the king to be no longer troubled, for there is a man of the highest rank – invariably, as would appear, overlooked and forgotten till the critical moment, in spite of his long series of triumphs and achievements – who was quite able to read the fearful augury, as he had often done before, when all others had been foiled by Him who "frustrateth the tokens of the liars and maketh diviners mad."439 Strange that he should not have been thought of, though "the king thy father, the king, I say, thy father, made him master of the whole college of mages and astrologers. Let Belshazzar send for Belteshazzar, and he would untie the knot and read the awful enigma."440

Then, Daniel was summoned; and since the king "has heard of him, that the spirit of the gods is in him, and that light and understanding and excellent wisdom is found in him," and that he is one who can interpret dreams, and unriddle hard sentences and untie knots, he shall have the scarlet robe, and the golden chain, and the seat among the triumvirs, if he will read and interpret the writing.

"Let thy gifts be thine, and thy rewards to another,"441 answered the seer, with fearless forthrightness: "yet, O king, I will read and interpret the writing." Then, after reminding him of the consummate power and majesty of his father Nebuchadrezzar; and how his mind had become indurated with pride; and how he had been stricken with lycanthropy, "till he knew that the Most High God ruled in the kingdom of men"; and that, in spite of all this, he, Belshazzar, in his infatuation, had insulted the Most High God by profaning the holy vessels of His Temple in a licentious revelry in honour of idols of gold, silver, brass, iron, and stone, which neither see, nor know, nor hear, – for this reason (said the seer) had the hollow hand been sent and the writing stamped upon the wall.

And now what was the writing? Daniel at the first glance had read that fiery quadrilateral of letters, looking like the twelve gems of the high priest's ephod with the mystic light gleaming upon them.

Four names of weight.442

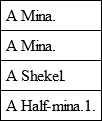

1. Journal Asiatique, 1886. (Comp. Nöldeke, Ztschr. für Assyriologie, i. 414-418; Kamphausen, p. 46.) It is M. Clermont-Ganneau who has the credit of discovering what seems to be the true interpretation of these mysterious words. M'nê (Heb. Maneh) is the Greek μνᾶ, Lat. mina, which the Greeks borrowed from the Assyrians. Tekel (in the Targum of Onkelos tîkla) is the Hebrew shekel. In the Mishnah a half-mina is called peras, and an Assyrian weight in the British Museum bears the inscription perash in the Aramaic character. (See Bevan, p. 106; Schrader, s. v. "Mene" in Riehm, R.W.B.) Peres is used for a half-mina in Yoma, f. 4, 4; often in the Talmud; and in Corp. Inscr. Sem., ii. 10 (Behrmann).

What possible meaning could there be in that? Did it need an archangel's colossal hand, flashing forth upon a palace-wall to write the menace of doom, to have inscribed no more than the names of four coins or weights? No wonder that the Chaldeans could not interpret such writing!

It may be asked why they could not even read it, since the words are evidently Aramaic, and Aramaic was the common language of trade. The Rabbis say that the words, instead of being written from right to left, were written κιονηδόν, "pillar-wise," as the Greeks called it, from above downwards: thus —

Read from left to right, they would look like gibberish; read from above downwards, they became clear as far as the reading was concerned, though their interpretation might still be surpassingly enigmatic.

But words may stand for all sorts of mysterious meanings; and in the views of analogists – as those are called who not only believe in the mysterious force and fascination of words, but even in the physiological quality of sounds – they may hide awful indications under harmless vocables. Herein lay the secret.

A mina! a mina! Yes; but the names of the weights recall the word m'nah, "hath numbered": and "God hath numbered thy kingdom and finished it."

A shekel! Yes; t'qilta: "Thou hast been weighed in a balance and found wanting."

Peres– a half-mina! Yes; but p'rîsath: "Thy kingdom has been divided, and given to the Medes and Persians."443

At this point the story is very swiftly brought to a conclusion, for its essence has been already given. Daniel is clothed in scarlet, and ornamented with the chain of gold, and proclaimed triumvir.444

But the king's doom is sealed! "That night was Belshazzar, king of the Chaldeans, slain." His name meant, "Bel! preserve thou the king!" But Bel bowed down, and Nebo stooped, and gave no help to their votary.

"Evil things in robes of sorrowAssailed the monarch's high estate;Ah, woe is me! for never morrowShall dawn upon him desolate!And all about his throne the gloryThat blushed and bloomedIs but an ill-remembered storyOf the old time entombed.""And Darius the Mede took the kingdom, being about sixty-two years old."

As there is no such person known as "Darius the Mede," the age assigned to him must be due either to some tradition about some other Darius, or to chronological calculations to which we no longer possess the key.445