полная версия

полная версияTheodore Watts-Dunton: Poet, Novelist, Critic

It might almost be said, indeed, that Sincerity and Conscience, the two angels that bring to the poet the wonders of the poetic dream, bring him also the deepest, truest delight of form. It might almost be said that by aid of sincerity and conscience the poet is enabled to see more clearly than other men the eternal limits of his own art – to see with Sophocles that nothing, not even poetry itself, is of any worth to man, invested as he is by the whole army of evil, unless it is in the deepest and highest sense good, unless it comes linking us all together by closer bonds of sympathy and pity, strengthening us to fight the foes with whom fate and even nature, the mother who bore us, sometimes seem in league – to see with Milton that the high quality of man’s soul which in English is expressed by the word virtue is greater than even the great poem he prized, greater than all the rhythms of all the tongues that have been spoken since Babel – and to see with Shakespeare and with Shelley that the high passion which in England is called love is lovelier than all art, lovelier than all the marble Mercuries that ‘await the chisel of the sculptor’ in all the marble hills.”

The reason why the criticism of the hour does not always give Mr. Watts-Dunton the place accorded to him by his great contemporaries is not any lack of generosity: it arises from the unprecedented, not to say eccentric, way in which his poetry has reached the public. In this respect alone, apart from its great originality, ‘The Coming of Love’ is a curiosity of literature. I know nothing in the least like the history of this poem. It was written, circulated in manuscript among the very elite of English letters, and indeed partly published in the ‘Athenæum,’ very nearly a quarter of a century ago. I have before alluded to Mrs. Chandler Moulton’s introduction to Philip Bourke Marston’s poems, where she says that it was Mr. Watts-Dunton’s poetry which won for him the friendship of Tennyson, Rossetti, Morris, and Swinburne. Yet for lustre after lustre it was persistently withheld from the public; cenacle after poetic cenacle rose, prospered and faded away, and still this poet, who was talked of by all the poets and called ‘the friend of all the poets,’ kept his work back until he had passed middle age. Then, at last, owing I believe to the energetic efforts of Mr. John Lane, who had been urging the matter for something like five years, he launched a volume which seized upon the public taste and won a very great success so far as sales go. It is now in its sixth edition. There can be no doubt whatever that if the book had appeared, as it ought to have appeared, at the time it was written, critics would have classed the poet among his compeers and he would have come down to the present generation, as Swinburne has come down, as a classic. But, as I have said, it is not in the least surprising that, notwithstanding Rossetti’s intense admiration of the poem, notwithstanding the fact that Morris intended to print it at the Kelmscott Press, and notwithstanding the fact that Swinburne, in dedicating the collected edition of his works to Mr. Watts-Dunton, addresses him as a poet of the greatest authority – it is only the true critics who see in the right perspective a poet who has so perversely neglected his chances. If his time of recognition has not yet fully come, this generation is not to blame. The poet can blame only himself, although to judge by Rossetti’s words, and by the following lines from Dr. Hake’s ‘New Day,’ he is indifferent to that: —

You tell me life is all too rich and brief,Too various, too delectable a game,To give to art, entirely or in chief;And love of Nature quells the thirst for fame.The ‘parable poet’ then goes on to give voice to the opinion, not only of himself, but of most of the great poets of the mid-Victorian epoch: —

You who in youth the cone-paved forest sought,Musing until the pines to musing fell;You who by river-path the witchery caughtOf waters moving under stress of spell;You who the seas of metaphysics crossed,And yet returned to art’s consoling haven —Returned from whence so many souls are lost,With wisdom’s seal upon your forehead graven —Well may you now abandon learning’s seat,And work the ore all seek, not many find;No sign-post need you to direct your feet,You draw no riches from another’s mind.Hail Nature’s coming; bygone be the past;Hail her New Day; it breaks for man at last.Fulfil the new-born dream of Poesy!Give her your life in full, she turns from less —Your life in full – like those who did not die,Though death holds all they sang in dark duress.You, knowing Nature to the throbbing core,You can her wordless prophecies rehearse.The murmers others heard her heart outpourSwell to an anthem in your richer verse.If wider vision brings a wider scopeFor art, and depths profounder for emotion,Yours be the song whose master-tones shall opeA new poetic heaven o’er earth and ocean.The New Day comes apace; its virgin fameBe yours, to fan the fiery soul to flame.Indeed, he has often said to me: ‘There is a tide in the affairs of men, and I did not throw myself upon my little tide until it was too late, and I am not going to repine now.’ For my part, I have been a student of English poetry all my life – it is my chief subject of study – and I predict that when poetic imagination is again perceived to be the supreme poetic gift, Mr. Watts-Dunton’s genius will be acclaimed. In respect of imaginative power, apart from the other poetic qualities – ‘the power of seeing a dramatic situation and flashing it upon the physical senses of the listener,’ none of his contemporaries have surpassed him.

I have said in print more than once that I, a Celt myself, can see more Celtic glamour in his poetry than in many of the Celtic poets of our time. And, if we are to judge by the vogue of ‘The Coming of Love’ and ‘Aylwin’ in Wales, the Welsh people seem to see it very clearly. Take, for instance, the sonnet called ‘The Mirrored Stars’ again, given on page 29. It is impossible for Celtic glamour to go further than this; and yet it is rarely noted by critics in discussing the Celtic note in poetry.

In order fully to understand ‘The Coming of Love’ it is necessary to bear in mind a distinction between the two kinds of poetry upon which Mr. Watts-Dunton has often dwelt. “There are,” he tells us, “but two kinds of poetry, but two kinds of art – that which interprets, and that which represents. ‘Poetry is apparent pictures of unapparent realities,’ says the Eastern mind through Zoroaster; ‘the highest, the only operation of art is representation (Gestaltung),’ says the Western mind through Goethe. Both are right.” Madame Galimberti has called Mr. Watts-Dunton ‘the poet of the sunrise’: There are richer descriptions of sunrise in ‘Aylwin’ and ‘The Coming of Love’ than in any other writer I know. “Few poets,” Mr. Watts-Dunton says, “have been successful in painting a sunrise, for the simple reason that, save through the bed-curtains, they do not often see one. They think that all they have to do is to paint a sunset, which they sometimes do see, and call it a sunrise. They are entirely mistaken, however; the two phenomena are both like and unlike. Between the cloud-pageantry of sunrise and of sunset the difference to the student of Nature is as apparent as is the difference to the poet between the various forms of his art.”

‘The Coming of Love’ shows that independence of contemporary vogues and influences which characterizes all Mr. Watts-Dunton’s work, whether in verse or prose, whether in romance or criticism, or in that analysis and exposition of the natural history of minds about which Sainte Beuve speaks. It was as a poet that his energies were first exercised, but this for a long time was known only to his poetical friends. His criticism came many years afterwards, and, as Rossetti used to say, ‘his critical work consists of generalizations of his own experience in the poet’s workshop.’ For many years he was known only in his capacity as a critic. James Russell Lowell is reported to have said: ‘Our ablest critics hitherto have been 18-carat; Theodore Watts goes nearer the pure article.’ Mr. William Sharp, in his study of Rossetti, says: ‘In every sense of the word the friendship thus begun resulted in the greatest benefit to the elder writer, the latter having greater faith in Mr. Watts-Dunton’s literary judgment than seems characteristic with so dominant and individual an intellect as that of Rossetti. Although the latter knew well the sonnet-literature of Italy and England, and was a much-practised master of the heart’s key himself, I have heard him on many occasions refer to Theodore Watts as having still more thorough knowledge on the subject, and as being the most original sonnet-writer living.’

‘Aylwin’ and ‘The Coming of Love’ are vitally connected with the poet’s peculiar critical message. Henry Aylwin and Percy Aylwin may be regarded as the embodiment of his philosophy of life. The very popularity of ‘Aylwin’ and ‘The Coming of Love’ is apt to make readers forget the profundity of the philosophical thought upon which they are based, although this profundity has been indicated by such competent critics as Dr. Robertson Nicoll in the ‘Contemporary Review,’ M. Maurice Muret in the ‘Journal des Débats,’ and other thoughtful writers. Upon the inner meaning of the romance and the poem I have, however, ideas of my own to express, which are not in full accordance with any previous criticisms. To me it seems that the two cousins, Henry Aylwin of the romance, and Percy Aylwin of the poem, are phases of a modern Hamlet, a Hamlet who has travelled past the pathetic superstitions of the old cosmogonies to the last milestone of doubting hope and questioning fear, a Hamlet who stands at the portals of the outer darkness, gazing with eyes made wistful by the loss of a beloved woman. In both the romance and the poem the theme is love at war with death. Mr. Watts-Dunton, in his preface to the illustrated edition of ‘Aylwin’ says: —

“It is a story written as a comment on Love’s warfare with death – written to show that, confronted as man is every moment by signs of the fragility and brevity of human life, the great marvel connected with him is not that his thoughts dwell frequently upon the unknown country beyond Orion, where the beloved dead are loving us still, but that he can find time and patience to think upon anything else: a story written further to show how terribly despair becomes intensified when a man has lost – or thinks he has lost – a woman whose love was the only light of his world – when his soul is torn from his body, as it were, and whisked off on the wings of the ‘viewless winds’ right away beyond the farthest star, till the universe hangs beneath his feet a trembling point of twinkling light, and at last even this dies away and his soul cries out for help in that utter darkness and loneliness. It was to depict this phase of human emotion that both ‘Aylwin’ and ‘The Coming of Love’ were written. They were missives from the lonely watch-tower of the writer’s soul, sent out into the strange and busy battle of the world – sent out to find, if possible, another soul or two to whom the watcher was, without knowing it, akin. In ‘Aylwin’ the problem is symbolized by the victory of love over sinister circumstance, whereas in the poem it is symbolized by a mystical dream of ‘Natura Benigna.’

In ‘The Coming of Love’ Percy Aylwin is a poet and a sailor, with such an absorbing love for the sea that he has no room for any other passion; to him an imprisoned seabird is a sufferer almost more pitiable than any imprisoned man, as will be seen by the opening section of the poem, ‘Mother Carey’s Chicken.’ On seeing a storm-petrel in a cage on a cottage wall near Gypsy Dell, he takes down the cage in order to release the bird; then, carrying the bird in the cage, he turns to cross a rustic wooden bridge leading past Gypsy Dell, when he suddenly comes upon a landsman friend of his, a Romany Rye, who is just parting from a young gypsy-girl. Gazing at her beauty, Percy stands dazzled and forgets the petrel. It is symbolical of the inner meaning of the story that the bird now flies away through the half-open door. From that moment, through the magic of love, the land to Percy is richer than the sea: this ends the first phase of the story. The first kiss between the two lovers is thus described: —

If only in dreams may Man be fully blest,Is heaven a dream? Is she I claspt a dream?Or stood she here even now where dew-drops gleamAnd miles of furze shine yellow down the West?I seem to clasp her still – still on my breastHer bosom beats: I see the bright eyes beam.I think she kissed these lips, for now they seemScarce mine: so hallowed of the lips they pressed.Yon thicket’s breath – can that be eglantine?Those birds – can they be Morning’s choristers?Can this be Earth? Can these be banks of furze?Like burning bushes fired of God they shine!I seem to know them, though this body of minePassed into spirit at the touch of hers!Percy stays with the gypsies, and the gypsy-girl, Rhona, teaches him Romany. This arouses the jealousy of a gypsy rival – Herne the ‘Scollard.’ Percy Aylwin’s family afterwards succeeds in separating him from her, and he is again sent to sea. While cruising among the coral islands he receives the letter from Rhona which paints her character with unequalled vividness: —

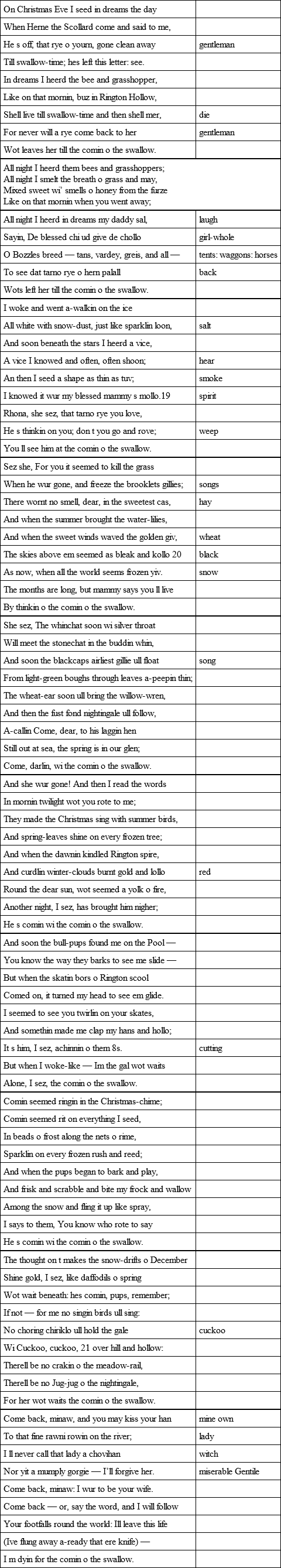

RHONA’S LETTER

19. Mostly pronounced ‘mullo,’ but sometimes in the East Midlands ‘mollo.’

20. Mostly pronounced ‘kaulo,’ but sometimes in the East Midlands ‘kollo.’

21. The gypsies are great observers of the cuckoo, and call certain spring winds ‘cuckoo storms,’ because they bring over the cuckoo earlier than usual.

Percy returns to England and reaches Gypsy Dell at the very moment when ‘the Schollard,’ maddened by the discovery that Rhona is to meet Percy that night, has drawn his knife upon the girl under the starlight by the river-bank. Percy on one side of the river witnesses the death-struggle on the other side without being able to go to Rhona’s assistance. But the girl hurls her antagonist into the water, and he is drowned. There are other witnesses – the stars, whose reflected light, according to a gypsy superstition, writes in the water, just above where the drowned man sank, mysterious runes, telling the story of the deed. For a Romany woman who marries a Gorgio the penalty is death. Nevertheless, Rhona marries Percy. I will quote the sonnets describing Rhona as she wakes in the tent at dawn: —

The young light peeps through yonder trembling chinkThe tent’s mouth makes in answer to a breeze;The rooks outside are stirring in the treesThrough which I see the deepening bars of pink.I hear the earliest anvil’s tingling clinkFrom Jasper’s forge; the cattle on the leasBegin to low. She’s waking by degrees:Sleep’s rosy fetters melt, but link by link.What dream is hers? Her eyelids shake with tears;The fond eyes open now like flowers in dew:She sobs I know not what of passionate fears:“You’ll never leave me now? There is but you;I dreamt a voice was whispering in my ears,‘The Dukkeripen o’ stars comes ever true.’”She rises, startled by a wandering beeBuzzing around her brow to greet the girl:She draws the tent wide open with a swirl,And, as she stands to breathe the fragrancyBeneath the branches of the hawthorn tree —Whose dews fall on her head like beads of pearl,Or drops of sunshine firing tress and curl —The Spirit of the Sunrise speaks to me,And says, ‘This bride of yours, I know her well,And so do all the birds in all the bowersWho mix their music with the breath of flowersWhen greetings rise from river, heath and dell.See, on the curtain of the morning hazeThe Future’s finger writes of happy days.’Rhona, half-hidden by ‘the branches of the hawthorn tree,’ stretches up to kiss the white and green May buds overhanging the bridal tent, while Percy Aylwin stands at the tent’s mouth and looks at her: —

Can this be she, who, on that fateful dayWhen Romany knives leapt out at me like stingsHurled back the men, who shrank like stricken thingsFrom Rhona’s eyes, whose lightnings seemed to slay?Can this be she, half-hidden in the may,Kissing the buds for ‘luck o’ love’ it brings,While from the dingle grass the skylark springsAnd merle and mavis answer finch and jay?[He goes up to the hawthorn, pulls the branchesapart, and clasps her in his arms.Can she here, covering with her childish kissesThese pearly buds – can she so soft, so tender,So shaped for clasping – dowered of all love-blisses —Be my fierce girl whose love for me would send her,An angel storming hell, through death’s abysses,Where never a sight could fright or power could bend her?But Rhona is haunted by forebodings, and one night when the lovers are on the river she reads the scripture of the stars. I must give here the sonnet quoted on page 29: —

The mirrored stars lit all the bulrush-spears,And all the flags and broad-leaved lily-isles;The ripples shook the stars to golden smiles,Then smoothed them back to happy golden spheres.We rowed – we sang; her voice seemed in mine earsAn angel’s, yet with woman’s dearer wiles;But shadows fell from gathering cloudy pilesAnd ripples shook the stars to fiery tears.What shaped those shadows like another boatWhere Rhona sat and he Love made a liar?There, where the Scollard sank, I saw it float,While ripples shook the stars to symbols dire;We wept – we kissed – while starry fingers wrote,And ripples shook the stars to a snake of fire.The most tragically dramatic scene in the poem is that in which Percy confronts the cosmic mystery, defying its menace. The stars write in the river: —

Falsehold can never shield her: Truth is strong.

Percy reads the rune and answers: —

I read your rune: is there no pity, then,In Heav’n that wove this net of life for men?Have only Hell and Falsehood heart for ruth?Show me, ye mirrored stars, this tyrant Truth —King that can do no wrong!Ah! Night seems opening! There, above the skies,Who sits upon that central sun for throneRound which a golden sand of worlds is strown,Stretching right onward to an endless ocean,Far, far away, of living, dazzling motion?Hearken, King Truth, with pictures in thine eyesMirrored from gates beyond the furthest portalOf infinite light, ’tis Love that stands immortal,The King of Kings.The gypsies read the starry rune, and, discovering Rhona’s secret, secretly slay her. Percy, having returned to Gypsy Dell, vainly tries to find her grave. Then he flies from the dingle, lest the memory of Rhona should drive him mad, and lives alone in the Alps, where he passes into the strange ecstasy, described in the sonnet called ‘Natura Maligna,’ which has been much discussed by the critics: —

The Lady of the Hills with crimes untoldFollowed my feet with azure eyes of prey;By glacier-brink she stood – by cataract-spray —When mists were dire, or avalanche-echoes rolled.At night she glimmered in the death-wind cold,And if a footprint shone at break of day,My flesh would quail, but straight my soul would say:‘’Tis hers whose hand God’s mightier hand doth hold.’I trod her snow-bridge, for the moon was bright,Her icicle-arch across the sheer crevasse,When lo, she stood!.. God made her let me pass,Then felled the bridge!.. Oh, there in sallow light,There down the chasm, I saw her cruel, white,And all my wondrous days as in a glass.This awful vision, quick with supernatural seership, is unique in poetry. Sir George Birdwood, the orientalist, wrote in the ‘Athenæum’ of February 5, 1881: “Even in its very epithets it is just such a hymn as a Hindu Puritan (Saivite) would address to Kali (‘the malignant’) or Parvati (‘the mountaineer’). It is to be delivered from her that Hindus shriek to God in the delirium of their fear.”

Then we are shown Percy standing at midnight in front of his hut, while New Year’s morning is breaking: —

Through Fate’s mysterious warp another weftOf days is cast; and see! Time’s star-built throne,From which he greets a new-born year, is shownBetween yon curtains where the clouds are cleft!Old Year, while here I stand, with heart bereftOf all that was its music – stand alone,Remembering happy hours for ever flown,Impatient of the leaden minutes left —The plaudits of mankind that once gave pleasure,The chidings of mankind that once gave pain,Seem in this hermit hut beyond all measureBarren and foolish, and I cry, ‘No grain,No grain, but winnowings in the harvest sieve!’And yet I cannot join the dead – and live.Old Year, what bells are ringing in the NewIn England, heedless of the knells they ringTo you and those whose sorrow makes you clingEach to the other ere you say adieu! —I seem to hear their chimes – the chimes we knewIn those dear days when Rhona used to sing,Greeting a New Year’s Day as bright of wingAs this whose pinions soon will rise to view.If these dream-bells which come and mock mine earsCould bring the past and make it live again,Yea, live with every hour of grief and pain,And hopes deferred and all the grievous fears —And with the past bring her I weep in vain —Then would I bless them, though I blessed in tears.[The clouds move away and show thestars in dazzling brightness.Those stars! they set my rebel-pulses beatingAgainst the tyrant Sorrow, him who droveMy footsteps from the Dell and haunted Grove —They bring the mighty Mother’s new-year greeting:‘All save great Nature is a vision fleeting’ —So says the scripture of those orbs above.‘All, all,’ I cry, ‘except man’s dower of love! —Love is no child of Nature’s mystic cheating!’And yet it comes again, the old desireTo read what yonder constellations writeOn river and ocean – secrets of the night —To feel again the spirit’s wondering fireWhich, ere this passion came, absorbed me quite,To catch the master-note of Nature’s lyre.New Year, the stars do not forget the Old!And yet they say to me, most sorely stungBy Fate and Death, ‘Nature is ever young,Clad in new riches, as each morning’s goldBlooms o’er a blasted land: be thou consoled:The Past was great, his harp was greatly strung;The Past was great, his songs were greatly sung;The Past was great, his tales were greatly told;The Past has given to man a wondrous world,But curtains of old Night were being upcurledWhilst thou wast mourning Rhona; things sublimeIn worlds of worlds were breaking on the sightOf Youth’s fresh runners in the lists of Time.Arise, and drink the wine of Nature’s light!’Finally, a dream prepares the sorrowing lover for the true reading of ‘The Promise of the Sunrise’ and the revelation of ‘Natura Benigna’: —

Beneath the loveliest dream there coils a fear:Last night came she whose eyes are memories now;Her far-off gaze seemed all forgetful howLove dimmed them once, so calm they shone and clear.‘Sorrow,’ I said, ‘has made me old, my dear;’Tis I, indeed, but grief can change the brow:Beneath my load a seraph’s neck might bow,Vigils like mine would blanch an angel’s hair.’Oh, then I saw, I saw the sweet lips move!I saw the love-mists thickening in her eyes —I heard a sound as if a murmuring doveFelt lonely in the dells of Paradise;But when upon my neck she fell, my love,Her hair smelt sweet of whin and woodland spice.And now ‘Natura Benigna’ reveals to him her mystic consolation: —

What power is this? What witchery wins my feetTo peaks so sheer they scorn the cloaking snow,All silent as the emerald gulfs below,Down whose ice-walls the wings of twilight beat?What thrill of earth and heaven – most wild, most sweet —What answering pulse that all the senses know,Comes leaping from the ruddy eastern glowWhere, far away, the skies and mountains meet?Mother, ’tis I, reborn: I know thee well:That throb I know and all it prophesies,O Mother and Queen, beneath the olden spellOf silence, gazing from thy hills and skies!Dumb Mother, struggling with the years to tellThe secret at thy heart through helpless eyes.This is not the pathetic fallacy. It is the poetic interpretation of the latest discovery of science, to wit, that dead matter is alive, and that the universe is an infinite stammering and whispering, that may be heard only by the poet’s finer ear.

The extracts I have given are sufficient to show the originality of Mr. Watts-Dunton’s poetry, both in subject and in form. The originality of any poet is seen, not in fantastic metrical experiments, but rather in new and original treatment of the metres natural to the genius of the language. In ‘The Coming of Love’ the poet has invented a new poetic form. Its object is to combine the advantages and to avoid the disadvantages of lyrical narrative, of poetic drama, of the prose novel, and of the prose play. In Tennyson’s ‘Maud’ and in Mr. Watts-Dunton’s other lyrical drama, “Christmas at the ‘Mermaid,’” the special functions of all the above mentioned forms are knit together in a new form. The story is told by brief pictures. In ‘The Coming of Love’ this method reaches its perfection. Lyrics, songs, elegaic quatrains, and sonnets, are used according to an inner law of the poet’s mind. The exaltation of these moments is intensified by the business parts of the narrative being summarized in bare prose. The interplay of thought, mood, and passion is revealed wholly by swift lyrical visions. In Dante’s ‘Vita Nuova’ a method something like this is adopted, but there the links are in a kind of poetical prose akin to the verse, and as Dante’s poems are all sonnets, there is no harmonic scheme of metrical music like that in ‘The Coming of Love.’ Here the very ‘rhyme-colour’ and the subtle variety of vowel sounds from beginning to end are evidently part of the metrical composition. Wagner’s music is the only modern art-form which is comparable with the metrical architecture of ‘The Coming of Love,’ and “Christmas at the ‘Mermaid.’” No one can fully understand the rhythmic triumph of these great poems who has not studied it by the light of Mr. Watts-Dunton’s theory of elaborate rhythmic effects in music formulated in his treatise on Poetry in the ‘Encyclopædia Britannica’ – a theory which shows that metrical and rhythmical art, as compared with the art of music, is still developing. Both these lyrical dramas ought to be carefully studied by all students of English metres.