полная версия

полная версияTheodore Watts-Dunton: Poet, Novelist, Critic

Had the mass of Mr. Watts-Dunton’s scattered writings been collected into volumes, or had a representative selection from them been made, their unity as to central idea with his imaginative work, and also the importance of that central idea, would have been brought prominently forward, and then there would have been no danger of his contribution to the latest movement – the anti-materialistic movement – of English thought and English feeling being left unrecognized. Lost such teachings as his never could have been, for, as Minto said years ago, their colour tinges a great deal of the literature of our time. The influence of the ‘Athenæum,’ not only in England, but also in America and on the Continent, was always very great – and very great of course must have been the influence of the writer who for a quarter of a century spoke in it with such emphasis. Therefore, if Mr. Watts-Dunton had himself collected or selected his essays, or if he had allowed any of his friends to collect or select them, this book of mine would not have been written, for more competent hands would have undertaken the task. But a study of work which, originally issued in fragments, now lies buried ‘full fathom five’ in the columns of various journals, could, I felt, be undertaken only by a cadet of letters like myself. There are many of us younger men who express views about Mr. Watts-Dunton’s work which startle at times those who are unfamiliar with it. And I, coming forward for the moment as their spokesman, have long had the desire to justify the faith that is in us, and in the wide and still widening audience his imaginative work has won. But I doubt if I should have undertaken it had I realized the magnitude of the task. For it must be remembered that the articles, called ‘reviews,’ are for the most part as unlike reviews as they can well be. No matter what may have been the book placed at the head of the article, it was used merely as an opportunity for the writer to pour forth generalizations upon literature and life, or upon the latest scientific speculations, or upon the latest reverie of philosophy, in a stream, often a torrent, coruscating with brilliancies, and alive with interwoven colours like that of the river in the mountains of Kaf described in his birthday sonnet to Tennyson. Take, for instance, that great essay on the Psalms which I have used as the key-note of this study. The book at the head of the review was not, as might have been supposed, a discourse learned, or philosophical, or emotional, upon the Psalms – but a little unpretentious metrical version of the Psalms by Lord Lorne. Only a clear-sighted and daring editor would have printed such an article as a review. But I doubt if there ever was a more prescient journalist than he who sat in the editorial chair at that time. A man of scholarly accomplishments and literary taste, he knew that an article such as this would be a huge success; would resound through the world of letters. The article, I believe, was more talked about in literary circles than any book that had come out during that month.

Again, take that definition of humour which I seized upon (page 384) to illustrate my exposition of that wonderful character in ‘Aylwin’ – Mrs. Gudgeon, a definition that seems, as one writer has said, to make all other talk about humour cheap and jejune. It is in a review of an extremely futile history of humour. Now let the reader consider the difficult task before a writer in my position – the task of searching for a few among the innumerable half-remembered points of interest that turn up in the most unexpected places. Of course, if the space allotted to me by my publishers had been unlimited, and if my time had been unlimited, I should have been able to give so large a number of excerpts from the articles as to make my selection really representative of what has been called the “modern Sufism of ‘Aylwin.’” But in this regard my publishers have already been as liberal and as patient as possible. After all, the best, as well as the easiest way, to show that ‘Aylwin,’ and ‘The Coming of Love,’ are but the imaginative expression of a poetic religion familiar to the readers of Mr. Watts-Dunton’s criticism for twenty-five years, is to quote an illuminating passage upon the subject from one of the articles in the ‘Athenæum.’ Moreover, I shall thus escape what I confess I dread – the sight of my own prose at the end of my book in juxtaposition to the prose of a past master of English style: —

“The time has not yet arrived for poetry to utilize even the results of science; such results as are offered to her are dust and ashes. Happily, however, nothing in science is permanent save mathematics. As a great man of science has said, ‘everything is provisional.’ Dr. Erasmus Darwin, following the science of his day, wrote a long poem on the ‘Loves of the Plants,’ by no means a foolish poem, though it gave rise to the ‘Loves of the Triangles,’ and though his grandson afterwards discovered that the plants do not love each other at all, but, on the contrary, hate each other furiously – ‘struggle for life’ with each other, ‘survive’ against each other – just as though they were good men and ‘Christians.’ But if a poet were to set about writing a poem on the ‘Hates of the Plants,’ nothing is more likely than that, before he could finish it, Mr. Darwin will have discovered that the plants do love after all; just as – after it was a settled thing that the red tooth and claw did all the business of progression – he delighted us by discovering that there was another factor which had done half the work – the enormous and very proper admiration which the females have had for the males from the very earliest forms upwards. In such a case, the ‘Hates of the Plants’ would have become ‘inadequate.’ Already, indeed, there are faint signs of the physicists beginning to find out that neither we nor the plants hate each other quite so much as they thought, and that Nature is not quite so bad as she seems. ‘She is an Æolian harp,’ says Novalis, ‘a musical instrument whose tones are the re-echo of higher strings within us.’ And after all there are higher strings within us just as real as those which have caused us to ‘survive,’ and poetry is right in ignoring ‘interpretations,’ and giving us ‘Earthly Paradises’ instead. She must wait, it seems; or rather, if this aspiring ‘century’ will keep thrusting these unlovely results of science before her eyes, she must treat them as the beautiful girl Kisāgotamī treated the ugly pile of charcoal. A certain rich man woke up one morning and found that all his enormous wealth was turned to a huge heap of charcoal. A friend who called upon him in his misery, suspecting how the case really stood, gave him certain advice, which he thus acted upon. ‘The Thuthe, following his friend’s instructions, spread some mats in the bazaar, and, piling them upon a large heap of his property which was turned into charcoal, pretended to be selling it. Some people, seeing it, said, “Why does he sell charcoal?” Just at this time a young girl, named Kisāgotamī, who was worthy to be owner of the property, and who, having lost both her parents, was in a wretched condition, happened to come to the bazaar on some business. When she saw the heap, she said, “My lord Thuthe, all the people sell clothes, tobacco, oil, honey, and treacle; how is it that you pile up gold and silver for sale?” The Thuthe said, “Madam, give me that gold and silver.” Kisāgotamī, taking up a handful of it, brought it to him. What the young girl had in her hand no sooner touched the Thuthe’s hand than it became gold and silver.’”

I cannot find a clearer note for the close of this book than that which sounds in one of the latest and one of the finest of Mr. Watts-Dunton’s sonnets. It was composed on the last night of the Nineteenth Century, a century which will be associated with many of the dear friends Mr. Watts-Dunton has lost, and, as I must think, associated also with himself. The lines have a very special charm for me, because they show the turn which the poet’s noble optimism has taken; they show that faith in my own generation which for so many years has illumined his work, and which has endeared him to us all. I wish I could be as hopeful as this nineteenth century poet with regard to the poets who will carry the torch of imagination and romance through the twentieth century; but whether or not there are any poets among us who are destined to bring in the Golden Fleece, it is good to see ‘the Poet of the Sunrise’ setting the trumpet of optimism to his lips, and heralding so cheerily the coming of the new argonauts: —

THE ARGONAUTS OF THE NEW AGEthe poet[In starlight, listening to the chimes in thedistance, which sound clear through theleafless trees.Say, will new heroes win the ‘Fleece,’ ye spheresWho – whether around some King of Suns ye rollOr move right onward to some destined goalIn Night’s vast heart – know what Great Morning nears?the starsSince Love’s Star rose have nineteen hundred yearsWritten such runes on Time’s remorseless scroll,Impeaching Earth’s proud birth, the human soul,That we, the bright-browed stars, grow dim with tears.Did those dear poets you loved win Light’s release?What ‘ship of Hope’ shall sail to such a world?[The night passes, and morning breaksgorgeously over the tree top.the poetYe fade, ye stars, ye fade with night’s decease!Above yon ruby rim of clouds empearled —There, through the rosy flags of morn unfurled —I see young heroes bring Light’s ‘Golden Fleece.’The End1

‘Studies in Prose.’

2

‘Chambers’s Encyclopædia,’ vol. x., p. 581.

3

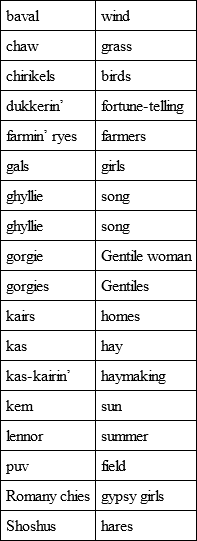

The meanings of the gypsy words are:

4

‘Notes and Queries,’ August 2, 1902.

5

Among the gypsies of all countries the happiest possible ‘Dukkeripen’ (i.e. prophetic symbol of Natura Mystica) is a hand-shaped golden cloud floating in the sky. It is singular that the same idea is found among races entirely disconnected with them – the Finns, for instance, with whom Ukko, the ‘sky god,’ or ‘angel of the sunrise,’ was called the ‘golden king’ and ‘leader of the clouds,’ and his Golden Hand was more powerful than all the army of Death. The ‘Golden Hand’ is sometimes called the Lover’s Dukkeripen.

6

Good-luck.

7

Child.

8

Pretty mouth.

9

A famous swimming dog belonging to the writer.

10

‘Notes and Queries,’ June 7, 1902.

11

Bosom.

12

I think I am not far wrong in saying that he whom Mr. Benson heard make this remark was a more illustrious poet than even D. G. Rossetti, the greatest poet indeed of the latter half of the nineteenth century, the author of ‘Erechtheus’ and ‘Atalanta in Calydon.’

13

As Mr. Swinburne has pronounced Mr. Stone’s translation to be in itself so fine as to be almost a work of genius, I will quote it here: —

Θειος ἀοιδόςFelix, qui potuit gentem illustrare canendo,quique decus patriae claris virtutibus additsuccurritque laboranti, tutamque pericliseruit, hostilesque minas avertit acerbodente lacessitae; bene, quicquid fecerit audax,explevisse iuvat: metam tenet ille quadrigis,praemia victor habet, quamvis tuba vivida famaeignoret titulos, vel si flammante sagittaoppugnet Livor quam mens sibi muniit arcem.quod si fata mihi virtutis gaudia tantaeinvideant, nec fas Anglorum extendere fineslatius, et nitidae primordia libertatis,Anglia cui praecepit iter, cantare poetae;si numeris laudare meam vel marte Parentemnon mihi contingat, nec Divom adsumere viresatque inconcessos sibi vindicet alter honores,dignior ille mihi frater, quem iure saluto —illum divino praestantem numine amabo.14

Philip Bourke Marston.

15

According to a Mohammedan tradition, the mountains of Kaf are entirely composed of gems, whose reflected splendours colour the sky.

16

‘Tennyson: A Memoir,’ by his son (1897), vol. ii. p. 479.

17

“Tanto è vero, che ‘Aylwin’ fu cominciato a scrivere in versi, e mutato di forma soltanto quando l’intreccio, in certo modo prendendo la mano al poeta, rese necessario un genere di sua natura meno astretto alla rappresentazione di scorcio; e che l’Avvento d’amore, ove le circostanze di fatto sono condensate in modo da dar pieno risalto al motivo filosofico, riesce una cosa, a mio credere, più perfetta.”

18

‘Notes and Queries,’ June 7, 1902.

19

‘England is a country that can never be conquered while the Sovereign thereof has the command of the sea.’ – Raleigh.