полная версия

полная версияThe Heart of the White Mountains, Their Legend and Scenery

Samuel Adams Drake

The Heart of the White Mountains, Their Legend and Scenery / Tourist's Edition

To JOHN G. WHITTIER:

An illustrious and venerated bard, who shares with you the love and honor of his countrymen, tells us that the poets are the best travelling companions. Like Orlando in the forest of Arden, they “hang odes on hawthorns and elegies on thistles.”

In the spirit of that delightful companionship, so graciously announced, it is to you, who have kindled on our aged summits that this volume is affectionately dedicated by

“The light that never was on sea or land,The consecration and the poet’s dream.”THE AUTHOR.PREFACE

THE very flattering reception which the sumptuous holiday edition of “The Heart of the White Mountains” received on its début has decided the Messrs. Harper to re-issue it in a more convenient and less expensive form, with the addition of a Tourist’s Appendix, and an Index farther adapting it for the use of actual travellers. While all the original features remain intact, these additions serve to render the references in the text intelligible to the uninstructed reader, and at the same time help to make a practical working manual. One or two new maps contribute to the same end.

I take the opportunity thus afforded me to say that, when “The Heart of the White Mountains” was originally prepared, I hoped it might go into the hands of those who, making the journey for the first time, feel the need of something different from the conventional guide-book of the day, and for whom it would also be, during the hours of travel or of leisure among the mountains, to some extent an entertaining as well as a useful companion. So far as author and publisher are concerned, that purpose is now realized.

Finally, I wrote the book because I could not help it.

Samuel Adams Drake.Melrose, January, 1882.

FIRST JOURNEY

I.

MY TRAVELLING COMPANIONS

“Si jeunesse savait! si viellesse pouvait!”ONE morning in September I was sauntering up and down the railway-station waiting for the slow hands of the clock to reach the hour fixed for the departure of the train. The fact that these hands never move backward did not in the least seem to restrain the impatience of the travellers thronging into the station, some with happy, some with anxious faces, some without trace of either emotion, yet all betraying the same eagerness and haste of manner. All at once I heard my name pronounced, and felt a heavy hand upon my shoulder.

“What!” I exclaimed, in genuine surprise, “is it you, colonel?”

“Myself,” affirmed the speaker, offering his cigar-case.

“And where did you drop from” – accepting an Havana; “the Blue Grass?”

“I reckon.”

“But what are you doing in New England, when you should be in Kentucky?”

“Doing, I? oh, well,” said my friend, with a shade of constraint; then with a quizzical smile, “You are a Yankee; guess.”

“Take care.”

“Guess.”

“Running away from your creditors?”

The colonel’s chin cut the air contemptuously.

“Running after a woman, perhaps?”

My companion quickly took the cigar from his lips, looked at me with mouth half opened, then stammered, “What in blue brimstone put that into your head?”

“Evidently you are going on a journey, but are dressed for an evening party,” I replied, comprising with a glance the colonel’s black suit, lavender gloves, and white cravat.

“Why,” said the colonel, glancing rather complacently at himself – “why we Kentuckians always travel so at home. But it’s now your turn; where are you going yourself?”

“To the mountains.”

“Good; so am I: White Mountains, Green Mountains, Rocky Mountains, or Mountains of the Moon, I care not.”

“What is your route?”

“I’m not at all familiar with the topography of your mountains. What is yours?”

“By the Eastern to Lake Winnipiseogee, thence to Centre Harbor, thence by stage and rail to North Conway and the White Mountain Notch.”

My friend purchased his ticket by the indicated route, and the train was soon rumbling over the bridges which span the Charles and Mystic. Farewell, Boston, city where, like thy railways, all extremes meet, but where I would still rather live on a crust moistened with east wind than cast my lot elsewhere.

When we had fairly emerged into the light and sunshine of the open country, I recognized my old acquaintance George Brentwood. At a gesture from me he came and sat opposite to us.

George Brentwood was a blond young man of thirty-four or thirty-five, with brown hair, full reddish beard, shrewdish blue eyes, a robust frame, and a general air of negligent repose. In a word, he was the antipodes of my companion, whose hair, eyebrows, and mustache were coal-black, eyes dark and sparkling, manner nervous, and his attitudes careless and unconstrained, though not destitute of a certain natural grace. Both were men to be remarked in a crowd.

“George,” said I, “permit me to introduce my friend Colonel Swords.”

After a few civil questions and answers, George declared his destination to be ours, and was cordially welcomed to join us. By way of breaking the ice, he observed,

“Apropos of your title, colonel, I presume you served in the Rebellion?”

The colonel hitched a little on his seat before replying. Knowing him to be a very modest man, I came to his assistance. “Yes,” said I, “the colonel fought hard and bled freely. Let me see, where were you wounded?”

“Through the chest.”

“No, I mean in what battle?”

“Spottsylvania.”

“Left on the field for dead, and taken prisoner,” I finished.

George is a fellow of very generous impulses. “My dear sir,” said he, effusively, grasping the colonel’s hand, “after what you have suffered for the old flag, you can need no other passport to the gratitude and friendship of a New-Englander. Count me as one of your debtors. During the war it was my fortune – my misfortune, I should say – to be in a distant country; otherwise we should have been found fighting shoulder to shoulder under Grant, or Sherman, or Sheridan, or Thomas.

The colonel’s color rose. He drew himself proudly up, cleared his throat, and said, laconically, “Hardly, stranger, seeing that I had the honor to fight under the Confederate flag.”

You have seen a tortoise suddenly draw back into his shell. Well, George as suddenly retreated into his. For an instant he looked at the Southron as one might at a confessed murderer; then stammered out a few random and unmeaning words about mistaken sense of duty – gallant but useless struggle, you know – drew a newspaper from his pocket, and hid his confusion behind it.

Fearing my fiery Kentuckian might let fall some unlucky word that would act like a live coal dropped on the tortoise’s back, I hastened to interpose. “But really, colonel,” I urged, returning to the charge, “with the Blue Ridge always at your back, I wager you did not come a thousand miles merely to see our mountains. Come, what takes you from Lexington?”

“A truant disposition.”

“Nothing else?”

His dark face grew swarthy, then pale. He looked at me doubtfully a moment, and then leaned close to my ear. “You guessed it,” he whispered.

“A woman?”

“Yes; you know that I was taken prisoner and sent North. Through the influence of a friend who had known my family before the war, I was allowed to pass my first days of convalescence in a beautiful little village in Berkshire. There I was cured of the bullet, but received a more mortal wound.”

“What a misfortune!”

“Yes; no; confound you, let me finish.”

“Helen, the daughter of the gentleman who procured my transfer from the hospital to his pleasant home” (the proud Southerner would not say his benefactor), “was a beautiful creature. Let me describe her to you.”

“Oh,” I hastened to say, “I know her.” Like all lovers, that subject might have a beginning but no ending.

“You?”

“Of course. Listen. Yellow hair, rippling ravishingly from an alabaster forehead, pink cheeks, pouting lips, dimpled chin, snowy throat – ”

The colonel made a gesture of impatience. “Pshaw, that’s a type, not a portrait. Well, the upshot of it was that I was exchanged, and ordered to report at Baltimore for transportation to our lines. Imagine my dismay. No, you can’t, for I was beginning to think she cared for me, and I was every day getting deeper and deeper in love. But to tell her! That posed me. When alone with her, my cowardly tongue clove to the roof of my mouth. Once or twice I came very near bawling out, ‘I love you!’ just as I would have given an order to a squadron to charge a battery.”

“Well; but you did propose at last?”

“Oh yes.”

“And was accepted.”

The colonel lowered his head, and his face grew pinched.

“Refused gently, but positively refused.”

“Come,” I hazarded, thinking the story ended, “I do not like your Helen.”

“Why?”

“Because either you are mistaken, or she seems just a little of a coquette.”

“Oh, you don’t know her,” said the colonel, warmly; “when we parted she betrayed unusual agitation – for her; but I was cut to the quick by her refusal, and determined not to let her see how deeply I felt it. After the Deluge – you know what I mean – after the tragedy at Appomattox, I went back to the old home. Couldn’t stay there. I tried New Orleans, Cuba. No use.”

Something rose in the colonel’s throat, but he gulped it down and went on:

“The image of that girl pursues me. Did you ever try running away from yourself? Well, after fighting it out with myself until I could endure it no longer, I put pride in my pocket, came straight to Berkshire, only to find Helen gone.”

“That was unlucky; where?”

“To the mountains, of course. Everybody seems to be going there; but I shall find her.”

“Don’t be too sanguine. It will be like looking for a needle in a hay-stack. The mountains are a perfect Dædalian labyrinth,” I could not help saying, in my vexation. Instead of an ardent lover of nature, I had picked up the “baby of a girl.” But there was George Brentwood. I went over and sat by George.

It was generally understood that George was deeply enamored of a young and beautiful widow who had long ceased to count her love affairs, who all the world, except George, knew loved only herself, and who had therefore nothing left worth mentioning to bestow upon another. By nature a coquette, passionately fond of admiration, her self-love was flattered by the attentions of such a man as George, and he, poor fellow, driven one day to the verge of despair, the next intoxicated with the crumbs she threw him, was the victim of a species of slavery which was fast undermining his buoyant and generous disposition. The colonel was in hot pursuit of his adored Helen. Two words sufficed to acquaint me that George was escaping from his beautiful tormentor. At all events, I was sure of him.

“How charming the country is! What a delightful sense of freedom!” George drew a deep breath, and stretched his limbs luxuriously. “Shall we have an old-fashioned tramp together?” He continued, with assumed vivacity, “The deuce take me if I go back to town for a twelve-month. How we creep along! I feel exultation in putting the long miles between me and the accursed city,” said George, at last.

“You experience no regret, then, at leaving the city?”

George merely looked at me; but he could not have spoken more eloquently.

The train had just left Portsmouth, when the conductor entered the car holding aloft a yellow envelope. Every eye was instantly riveted upon it. Conversation ceased. For whom of the fifty or sixty occupants of the car had this flash overtaken the express train? In that moment the criminal realized the futility of flight, the merchant the uncertainty of his investments, the man of leisure all the ordinary contingencies of life. The conductor put an end to the suspense by demanding,

“Is Mr. George Brentwood in this car?”

In spite of an heroic effort at self-control, George’s hand trembled as he tore open the envelope; but as he read his face became radiant. Had he been alone I believe he would have kissed the paper.

“Your news is not bad?” I ventured to ask, seeing him relapse into a fit of musing, and noting the smile that came and went like a ripple on still water.

“Thank you, quite the contrary; but it is important that I should immediately return to Boston.”

“How unfortunate!”

George turned on me a fixed and questioning look, but made no reply.

“And the mountains?” I persisted.

“Oh, sink the mountains!”

I last saw George striding impatiently up and down the platform of the Rochester station, watch in hand. Without doubt he had received his recall. However, there was still the lovelorn colonel.

Never have I seen a man more thoroughly enraptured with the growing beauty of the scenery. I promised myself much enjoyment in his society, for his comments were both original and picturesque; so that by the time we arrived at Wolfborough I had already forgotten George and his widow.

There was the usual throng of idlers lounging about the pier with their noses in the air, and their hands in their pockets; perhaps more than the usual confusion, for the steamer merely touched to take and leave passengers. We went on board. As the bell tolled the colonel uttered an exclamation. He became all on a sudden transformed from a passive spectator into an excited and prominent actor in the scene. He gesticulated wildly, swung his hat, and shouted in a frantic way, apparently to attract the attention of some one in the crowd; failing in which he seized his luggage, took the stairs in two steps, and darting like a rocket among the astonished spectators, who divided to the right and left before his impetuous onset, was in the act of vigorously shaking hands with a hale old gentleman of fifty odd when the boat swung clear. He waved his unoccupied hand, and I saw his face wreathed in smiles. I could not fail to interpret the gesture as an adieu.

“Halloo!” I shouted, “what of the mountains?”

II.

INCOMPARABLE WINNIPISEOGEE

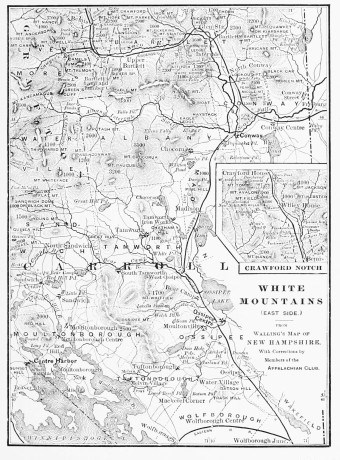

First a lakeTinted with sunset, next the wavy linesOf far receding hills. – Whittier.WHEN the steamer glides out of the land-locked inlet at the bottom of which Wolfborough is situated, one of those pictures, forever ineffaceable, presents itself. In effect, all the conditions of a picture are realized. Here is the shining expanse of the lake stretching away in the distance, and finally lost among tufted inlets and foliage-rounded promontories. To the right are the Ossipee mountains, dark, vigorously outlined, and wooded to their summits. To the left, more distant, rise the twin domes of the Belknap peaks. In front, and closing the view, the imposing Sandwich summits dominate the scene.

All these mountains seem advancing into the lake. They possess a special character of color, outline, or physiognomy which fixes them in the memory, not confusedly, but in the place appropriate to this beautiful picture, to its fine proportions, exquisite harmony, and general effectiveness. Even M. Chateaubriand, who maintains that mountains should only be seen from a distance – even he would have found in Winnipiseogee the perfection of his ideal mise en scène; for here they stand well back from the lake, so as to give the best effect of perspective.

Lovely as the lake is, the eye will rove among the mountains that we have come to see. They, and they alone, are the objects which have enticed us – entice us even now with a charm and mystery that we cannot pretend to explain. We do not wish it explained. We know that we are as free, as light of heart, as the birds that skim the placid surface of the lake, and coquet with their own shadows. The memory of those mountains is like snatches of music that come unbidden and haunt you perpetually.

Having taken in the grander features, the eye is occupied with its details. We see the lake quivering in sunshine. From bold summit to beautiful water the shores are clothed in most vivid green. The islands, which we believe to be floating gardens, are almost tropical in the luxuriance and richness of their vegetation. The deep shadows they fling down image each islet so faithfully that it seems, like Narcissus, gloating over its own beauty. Here and there a glimmer of water through the trees denotes secluded little havens. Boats float idly on the calm surface. Water-fowl rise and beat the glossy, dark water with startled wings. White tents appear, and handkerchiefs flutter from jutting points or headlands. Over all tower the mountains.

The steamer glided swiftly and noiselessly on, attended by the echo of her paddles from the shores. Dimpled waves, parting from her prow, rolled indolently in, and broke on the foam-fretted rocks. There was a warmth of color about these rocks, a pure transparency to the water, a brightness to the foliage, an invigorating strength in the mountains that exerted a cheerful influence upon our spirits.

As we advanced up the lake new and rare vistas rapidly succeeded. After leaving Long Island behind, the near ranges drew apart, holding us admiring and absorbed spectators of a moving panorama of distant summits. An opening appeared, through which Mount Washington burst upon us blue as lapis-lazuli, a chaplet of clouds crowning his imperial front. Slowly, majestically, he marches by, and now Chocorua scowls upon us. A murmur of admiration ran from group to group as these monumental figures were successively unveiled. Men kept silence, but women could not repress the exclamation, “How beautiful!” The two grandest types which these mountains enclose were thus displayed in the full splendor of noonday.

I should add that those who now saw Mount Washington for the first time, and whose curiosity was whetted by the knowledge that it was the highest peak of the whole family of mountains, openly manifested their disappointment. That Mount Washington! It was in vain to remind them that the eye traversed forty miles in its flight from lake to summit. Fault of perspective or not, the mountain was not nearly so high as they imagined. Chocorua, on the contrary, with its ashen spire and olive-green flanks, realized more fully their idea of a high mountain. One was near, the other far. Imagination fails to make a mountain higher than it looks. The mind takes its measure after the eye.

Our boat was now rapidly nearing Centre Harbor. On the right its progress gradually unmasking the western slopes of the Ossipee range, more fully opened the view of Chocorua and his dependent peaks. We were looking in the direction of Tamworth. Ossipee, and Conway. Red Hill, a detached mountain at the head of the lake, now moved into the gap, excluding further views of distant summits. Moosehillock, lofty but unimpressive, has for some time showed its flattened heights over the Sandwich Mountains, but is now sinking behind them. To the west, thronged with islands, is the long reach of water toward the outlet of the lake at Weirs.1

This lake was the highway over which Indian war-parties advanced or retreated during their predatory incursions from Canada. Many captives must have crossed it whom its mountain walls seemed forever destined to separate from friends and kindred. The Indians who inhabited villages at Winnipiseogee (Weirs), Ossipee, and Pigwacket (Fryeburg), were hostile; and from time to time during the old wars troops were marched from the English settlements to subdue them. These scouting-parties found the woods well stocked with bear, moose, and deer, and the lake with salmon-trout, some of which, according to the narrative before me, were three feet long, and weighed twelve pounds each.

Traces of Indian occupation remained up to the present century. Fishing-weirs and woodland paths were frequently discovered by the whites; but a greater curiosity than either is mentioned by Dr. Belknap, in his “History of New Hampshire,” who there tells of a pine-tree, standing on the shore of Winnipiseogee River, on which was carved a canoe with two men in it, supposed to have been a mark of direction to those who were expected to follow. Another was a tree in Moultonborough, standing near a carrying-place between two ponds. On this tree was a representation of one of their expeditions. The number of killed and the prisoners were shown by rude drawings of human beings, the former being distinguished by the mark of a knife across the throat. Even the distinction of sex was preserved in the drawing.

Centre Harbor is advantageously situated for a sojourn more or less prolonged. Although settled as early as 1755, it is, in common with the other lake towns, barren of history or tradition. Its greatest impulse is, beyond question, the tide of tourists which annually ebbs and flows among the most sequestered nooks, enriching this charming region like an inundation of the Nile. An anecdote will, however, serve to illustrate the character of the men who first subdued this wilderness. Our anecdote represents its hero a man of resources. His career proves him a man of courage. Although a veritable personage, let us call him General Hampton.

The fact that General Hampton lived in that only half-cleared atmosphere following the age of credulity and superstition, naturally accounts for the extraordinary legend concerning him which, for the rest, had its origin among his own friends and neighbors, who merely shared the general belief in the practice of diabolic arts, through compacts with the arch-enemy of mankind himself, universally prevailing in that day – yes, prevailing all over Christendom. By a mere legend, we are thus able to lay hold of the thread which conducts us back through the dark era of superstition and delusion, and which is now so amazing.

The general, says the legend, encountered a far more notable adversary than Abenaki warriors or conjurers, among whom he had lived, and whom it was the passion of his life to exterminate.

In an evil hour his yearning to amass wealth suddenly led him to declare that he would sell his soul for the possession of unbounded riches. Think of the devil, and he is at your elbow. The fatal declaration was no sooner made – the general was sitting alone by his fireside – than a shower of sparks came down the chimney, out of which stepped a man dressed from top to toe in black velvet. The astonished Hampton noticed that the stranger’s ruffles were not even smutted.

“Your servant, general,” quoth the stranger, suavely, “but let us make haste, if you please, for I am expected at the governor’s in a quarter of an hour,” he added, picking up a live coal with his thumb and forefinger and consulting his watch with it.

The general’s wits began to desert him. Portsmouth was five leagues, long ones at that, from Hampton House, and his strange visitor talked, with the utmost unconcern, of getting there in fifteen minutes. His astonishment caused him to stammer out,

“Then you must be the – ”

“Tush! what signifies a name?” interrupted the stranger, with a deprecating wave of the hand. “Come, do we understand each other? is it a bargain or not?”

At the talismanic word “bargain” the general pricked up his ears. He had often been heard to say that neither man nor devil could get the better of him in a trade. He took out his jack-knife and began to whittle. The devil took out his, and began to pare his nails.

“But what proof have I that you can perform what you promise?” demanded Hampton, pursing up his mouth, and contracting his bushy eyebrows.

The fiend ran his fingers carelessly through his peruke; a shower of golden guineas fell to the floor, and rolled to the four corners of the room. The general quickly stooped to pick up one; but no sooner had his fingers closed upon it than he uttered a yell. It was red-hot.

The devil chuckled. “Try again,” he said.

But Hampton shook his head, and retreated a step.

“Don’t be afraid.”

Hampton cautiously touched a coin. It was cool. He weighed it in his hand, and rung it on the table. It was full weight and true ring. Then he went down on his hands and knees, and began to gather up the guineas with feverish haste.