полная версия

полная версияMusic in the History of the Western Church

The chant appears to be the natural and fundamental form of music employed in all liturgical systems the world over, ancient and modern. The sacrificial song of the Egyptians, the Hebrews, and the Greeks was a chant, and this is the form of music adopted by the Eastern Church, the Anglican, and every system in which worship is offered in common and prescribed forms. The chant form is chosen because it does not make an independent artistic impression, but can be held in strict subordination to the sacred words; its sole function is to carry the text over with greater force upon the attention and the emotions. It is in this relationship of text and tone that the chant differs from true melody. The latter obeys musical laws of structure and rhythm; the music is paramount and the text accessory, and in order that the musical flow may not be hampered, the words are often extended or repeated, and may be compared to a flexible framework on which the tonal decoration is displayed. In the chant, on the other hand, this relation of text and tone is reversed; there is no repetition of words, the laws of structure and rhythm are rhetorical laws, and the music never asserts itself to the concealment or subjugation of the meaning of the text. The “jubilations” or “melismas,” which are frequent in the choral portions of the Plain Song system, particularly in the richer melodies of thee Mass, would seem at first thought to contradict this principle; in these florid melodic phrases the singer would appear to abandon himself to a sort of inspired rapture, giving vent to the emotions aroused in him by the sacred words. Here musical utterance seems for the moment to be set free from dependence upon word and symbol and to assert its own special prerogatives of expression, adopting the conception that underlies modern figurate music. These occasional ebullitions of feeling permitted in the chant are, however, only momentary; they relieve what would otherwise be an unvaried austerity not contemplated in the spirit of Catholic art; they do not violate the general principle of universality and objectiveness as opposed to individual subjective expression, – subordination to word and rite rather than purely musical self-assertion, – which is the theoretic basis of the liturgic chant system.

Chant is speech-song, probably the earliest form of vocal music; it proceeds from the modulations of impassioned speech; it results from the need of regulating and perpetuating these modulations when certain exigencies require a common and impressive form of utterance, as in religious rites, public rejoicing or mourning, etc. The necessity of filling large spaces almost inevitably involves the use of balanced cadences. Poetic recitation among ancient and primitive peoples is never recited in the ordinary level pitch of voice in speech, but always in musical inflections, controlled by some principle of order. Under the authority of a permanent corporate institution these inflections are reduced to a system, and are imposed upon all whose office it is to administer the public ceremonies of worship. This is the origin of the liturgic chant of ancient peoples, and also, by historic continuation, of the Gregorian melody. The Catholic chant is a projection into modern art of the altar song of Greece, Judaea, and Egypt, and through these nations reaches back to that epoch of unknown remoteness when mankind first began to conceive of invisible powers to be invoked or appeased. A large measure of the impressiveness of the liturgic chant, therefore, is due to its historic religious associations. It forms a connecting link between ancient religion and the Christian, and perpetuates to our own day an ideal of sacred music which is as old as religious music itself. It is a striking fact that only within the last six hundred or seven hundred years, and only within the bounds of Christendom, has an artificial form of worship music arisen in which musical forms have become emancipated from subjection to the rhetorical laws of speech, and been built up under the shaping force of inherent musical laws, gaining a more or less free play for the creative impulses of an independent art. The conception which is realized in the Gregorian chant, and which exclusively prevailed until the rise of the modern polyphonic system, is that of music in subjection to rite and liturgy, its own charms merged and, so far as conscious intention goes, lost in the paramount significance of text and action. It is for this reason, together with the historic relation of chant and liturgy, that the rulers of the Catholic Church have always labored so strenuously for uniformity in the liturgic chant as well as for its perpetuity. There are even churchmen at the present time who urge the abandonment of all the modern forms of harmonized music and the restoration of the unison chant to every detail of the service. A notion so ascetic and monastic can never prevail, but one who has fully entered into the spirit of the Plain Song melodies can at least sympathize with the reverence which such a reactionary attitude implies. There is a solemn unearthly sweetness in these tones which appeals irresistibly to those who have become habituated to them. They have maintained for centuries the inevitable comparison with every other form of melody, religious and secular, and there is reason to believe that they will continue to sustain all possible rivalry, until they at last outlive every other form of music now existing.

No one can obtain any proper conception of this magnificent Plain Song system from the examples which one ordinarily hears in Catholic churches, for only a minute part of it is commonly employed at the present day. Only in certain convents and a few churches where monastic ideas prevail, and where priests and choristers are enthusiastic students of the ancient liturgic song, can we hear musical performances which afford us a revelation of the true affluence of this mediaeval treasure. What we customarily hear is only the simpler intonings of the priest at his ministrations, and the eight “psalm tones” sung alternately by priest and choir. These “psalm tones” or “Gregorian tones” are plain melodic formulas, with variable endings, and are appointed to be sung to the Latin psalms and canticles. When properly delivered, and supported by an organist who knows the secret of accompanying them, they are exceedingly beautiful. They are but a hint, however, of the rich store of melodies, some of them very elaborate and highly organized, which the chantbooks contain, and which are known only to special students. To this great compendium belong the chants anciently assigned to those portions of the liturgy which are now usually sung in modern settings, – the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnus Dei, and the variable portions of the Mass, such as the Introits, Graduals, Prefaces, Offertories, Sequences, etc., besides the hymns sung at Vespers and the other canonical hours. Few have ever explored the bulky volumes which contain this unique bequest of the Middle Age; but one who has even made a beginning of such study, or who has heard the florid chants worthily performed in the traditional style, can easily understand the enthusiasm which these strains arouse in the minds of those who love to penetrate to the innermost shrines of Catholic devotional expression.

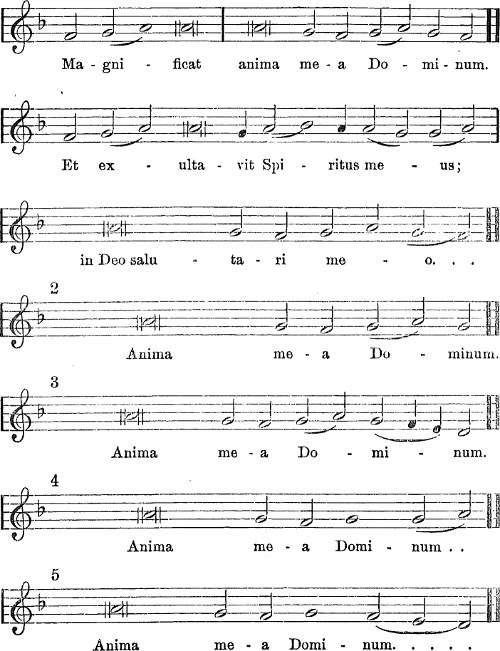

Example of Gregorian Tones. First Tone with its Endings.

[play]

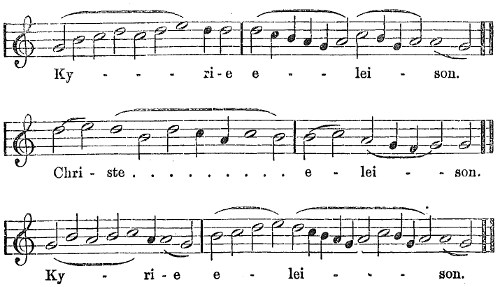

Example of a Florid Chant.

[play]

The theory and practice of the liturgic chant is a science of large dimensions and much difficulty. In the course of centuries a vast store of chant melodies has been accumulated, and in the nature of the case many variants of the older melodies – those composed before the development of a precise system of notation – have arisen, so that the verification of texts, comparison of authorities, and the application of methods of rendering to the needs of the complex ceremonial make this subject a very important branch of liturgical science.

The Plain Song may be divided into the simple and the ornate chants. In the first class the melodies are to a large extent syllabic (one note to a syllable), rarely with more than two notes to a syllable. The simplest of all are the tones employed in the delivery of certain prayers, the Epistle, Prophecy, and Gospel, technically known as “accents,” which vary but little from monotone. The most important of the more melodious simple chants are the “Gregorian tones” already mentioned. The inflections sung to the versicles and responses are also included among the simple chants.

The ornate chants differ greatly in length, compass, and degree of elaboration. Some of these melodies are exceedingly florid and many are of great beauty. They constitute the original settings for all the portions of the Mass not enumerated among the simple chants, viz., the Kyrie, Gloria, Introit, Prefaces, Communion, etc., besides the Sequences and hymns. Certain of these chants are so elaborate that they may almost be said to belong to a separate class. Examination of many of these extended melodies will often disclose a decided approach to regularity of form through the recurrence of certain definite melodic figures. “In the Middle Age,” says P. Wagner, “nothing was known of an accompaniment; there was not the slightest need of one. The substance of the musical content, which we to-day commit to interpretation through harmony, the old musicians laid upon melody. The latter accomplished in itself the complete utterance of the artistically aroused fantasy. In this particular the melismas, which carry the extensions of the tones of the melody, are a necessary means of presentation in mediaeval art; they proceed logically out of the principle of the unison melody.” “Text repetition is virtually unknown in the unison music of the Middle Age. While modern singers repeat an especially emphatic thought or word, the old melodists repeat a melody or phrase which expresses the ground mood of the text in a striking manner. And they not only repeat it, but they make it unfold, and draw out of it new tones of melody. This method is certainly not less artistic than the later text repetition; it comes nearer, also, to the natural expression of the devotionally inspired heart.”54

The ritual chant has its special laws of execution which involve long study on the part of one who wishes to master it. Large attention is given in the best seminaries to the purest manner of delivering the chant, and countless treatises have been written upon the subject. The first desideratum is an accurate pronunciation of the Latin, and a facile and distinct articulation. The notes have no fixed and measurable value, and are not intended to give the duration of the tones, but only to guide the modulation of the voice. The length of each tone is determined only by the proper length of the syllable. In this principle lies the very essence of Gregorian chant, and it is the point at which it stands in exact contradiction to the theory of modern measured music. The divisions of the chant are given solely by the text. The rhythm, therefore, is that of speech, of the prose text to which the chant tones are set. The rhythm is a natural rhythm, a succession of syllables combined into expressive groups by means of accent, varied pitch, and prolongations of tone. The fundamental rule for chanting is: “Sing the words with notes as you would speak them without notes.” This does not imply that the utterance is stiff and mechanical as in ordinary conversation; there is a heightening of the natural inflection and a grouping of notes, as in impassioned speech or the most refined declamation. Like the notes and divisions, the pauses also are unequal and immeasurable, and are determined only by the sense of the words and the necessity of taking breath.

In the long florid passages often occurring on a single vowel analogous rules are involved. The text and the laws of natural recitation must predominate over melody. The jubilations are not to be conceived simply as musical embellishments, but, on the contrary, their beauty depends upon the melodic accents to which they are joined in a subordinate position. These florid passages are never introduced thoughtlessly or without meaning, but they are strictly for emphasizing the thought with which they are connected; “they make the soul in singing fathom the deeper sense of the words, and to taste of the mysteries hidden within them.”55 The particular figures must be kept apart and distinguished from each other, and brought into union with each other, like the words, clauses, and sentences of an oration. Even these florid passages are dependent upon the influence of the words and their character of prayer.

The principles above cited concern the rhythm of the chant. Other elements of expression must also be taken into account, such as prolonging and shortening tones, crescendos and diminuendos, subtle changes of quality of voice or tone color to suit different sentiments. The manner of singing is also affected by the conditions of time and place, such as the degree of the solemnity of the occasion, and the dimensions and acoustic properties of the edifice in which the ceremony is held.

In the singing of the mediaeval hymn melodies, many beautiful examples of which abound in the Catholic office books, the above rules of rhythm and expression are modified as befits the more regular metrical character which the melodies derive from the verse. They are not so rigid, however, as would be indicated by the bar lines of modern notation, and follow the same laws of rhythm that would obtain in spoken recitation.

The liturgic chant of the Catholic Church has already been alluded to under its more popular title of “Gregorian.” Throughout the Middle Age and down to our own day nothing in history has been more generally received as beyond question than that the Catholic chant is entitled to this appellation from the work performed in its behalf by Pope Gregory I., called the Great. This eminent man, who reigned from 590 to 604, was the ablest of the succession of early pontiffs who formulated the line of policy which converted the barbarians of the North and West, brought about the spiritual and political autonomy of the Roman See, and confirmed its supremacy over all the churches of the West.

In addition to these genuine services historians have generally concurred in ascribing to him a final shaping influence upon the liturgic chant, with which, however, he probably had very little to do. His supposed work in this department has been divided into the following four details:

(1) He freed the church song from the fetters of Greek prosody.

(2) He collected the chants previously existing, added others, provided them with a system of notation, and wrote them down in a book which was afterwards called the Antiphonary of St. Gregory, which he fastened to the altar of St. Peter’s Church, in order that it might serve as an authoritative standard in all cases of doubt in regard to the true form of chant.

(3) He established a singing school in which he gave instruction.

(4) He added four new scales to the four previously existing, thus completing the tonal system of the Church.

The prime authority for these statements is the biography of Gregory I., written by John the Deacon about 872. Detached allusions to this pope as the founder of the liturgic chant appear before John’s day, the earliest being in a manuscript addressed by Pope Hadrian I. to Charlemagne in the latter part of the eighth century, nearly two hundred years after Gregory’s death. The evidences which tend to show that Gregory I. could not have had anything to do with this important work of sifting, arranging, and noting the liturgic melodies become strong as soon as they are impartially examined. In Gregory’s very voluminous correspondence, which covers every known phase of his restless activity, there is no allusion to any such work in respect to the music of the Church, as there almost certainly would have been if he had undertaken to bring about uniformity in the musical practice of all the churches under his administration. The assertions of John the Deacon are not confirmed by any anterior document. No epitaph of Gregory, no contemporary records, no ancient panegyrics of the pope, touch upon the question. Isidor of Seville, a contemporary of Gregory, and the Venerable Bede in the next century, were especially interested in the liturgic chant and wrote upon it, yet they make no mention of Gregory in connection with it. The documents upon which John bases his assertion, the so-called Gregorian Antiphonary, do not agree with the ecclesiastical calendar of the actual time of Gregory I.

In reply to these objections and others that might be given there is no answer but legend, which John the Deacon incorporated in his work, and which was generally accepted toward the close of the eleventh century. That this legend should have arisen is not strange. It is no uncommon thing in an uncritical age for the achievement of many minds in a whole epoch to be attributed to the most commanding personality in that epoch, and such a personality in the sixth and seventh centuries was Gregory the Great.

What, then, is the origin of the so-called Gregorian chant? There is hardly a more interesting question in the whole history of music, for this chant is the basis of the whole magnificent structure of mediaeval church song, and in a certain sense of all modern music, and it can be traced back unbroken to the earliest years of the Christian Church, the most persistent and fruitful form of art that the modern world has known. The most exhaustive study that has been devoted to this obscure subject has been undertaken by Gevaert, director of the Brussels Conservatory of Music, who has brought forward strong representation to show that the musical system of the early Church of Rome was largely derived from the secular forms of music practised in the private and social life of the Romans in the time of the empire, and which were brought to Rome from Greece after the conquest of that country B.C. 146. “No one to-day doubts,” says Gevaert, “that the modes and melodies of the Catholic liturgy are a precious remains of antique art.” “The Christian chant took its modal scales to the number of four, and its melodic themes, from the musical practice of the Roman empire, and particularly from the song given to the accompaniment of the kithara, the special style of music cultivated in private life. The most ancient monuments of the liturgic chant go back to the boundary of the fourth and fifth centuries, when the forms of worship began to be arrested in their present shape. Like the Latin language, the Greco-Roman music entered in like manner into the Catholic Church. Vocabulary and syntax are the same with the pagan Symmachus and his contemporary St. Ambrose; modes and rules of musical composition are identical in the hymns which Mesomedes addresses to the divinities of paganism and in the cantilenas of the Christian singers.” “The compilation and composition of the liturgic songs, which was traditionally ascribed to St. Gregory I., is in truth a work of the Hellenic popes at the end of the seventh and the beginning of the eighth centuries. The Antiphonarium Missarum received its definitive form between 682 and 715; the Antiphonarium Officii was already fixed under Pope Agathon (678-681).” In the fourth century, according to Gevaert, antiphons were already known in the East. St. Ambrose is said to have transplanted them into the West. Pope Celestine I. (422-472) has been called the founder of the antiphonal song in the Roman Church. Leo the Great (440-461) gave the song permanence by the establishment of a singing school in the neighborhood of St. Peter’s. Thus from the fifth century to the latter part of the seventh grew the treasure of melody, together with the unfolding of the liturgy. The four authentic modes were adaptations of four modes employed by the Greeks. The oldest chants are the simplest, and of those now in existence the antiphons of the Divine Office can be traced farthest back to the transition point from the Greco-Roman practice to that of the Christian Church. The florid chants were of later introduction, and were probably the contribution of the Greek and Syrian Churches.56

The Christian chants were, however, no mere reproductions of profane melodies. The groundwork of the chant is allied to the Greek melody; the Christian song is of a much richer melodic movement, bearing in all its forms the evidence of the exuberant spiritual life of which it is the chosen expression. The pagan melody was sung to an instrument; the Christian was unaccompanied, and was therefore free to develop a special rhythmical and melodic character unconditioned by any laws except those involved in pure vocal expression. The fact also that the Christian melodies were set to unmetrical texts, while the Greek melody was wholly confined to verse, marked the emancipation of the liturgic song from the bondage of strict prosody, and gave a wider field to melodic and rhythmic development.

It would be too much to say that Gevaert has completely made out his case. The impossibility of verifying the exact primitive form of the oldest chants, and the almost complete disappearance of the Greco-Roman melodies which are supposed to be the antecedent or the suggestion of the early Christian tone formulas, make a positive demonstration in such a case out of the question. Gevaert seems to rely mainly upon the identity of modes or keys which exists between the most ancient church melodies and those most in use in the kithara song. Other explanations, more or less plausible, have been advanced, and it is not impossible that the simpler melodies may have arisen in an idealization of the natural speech accent, with a view to procuring measured and agreeable cadences. Both methods – actual adaptations of older tunes and the spontaneous enunciation of more obvious melodic formulas – may have been allied in the production of the earlier liturgic chants. The laws that have been found valid in the development of all art would make the derivation of the ecclesiastical melodies from elements existing in the environment of the early Church a logical and reasonable supposition, even in the absence of documentary evidence.

There is no proof of the existence of a definite system of notation before the seventh century. The chanters, priests, deacons, and monks, in applying melodies to the text of the office, composed by aid of their memories, and their melodies were transmitted by memory, although probably with the help of arbitrary mnemonic signs. The possibility of this will readily be granted when we consider that special orders of monks made it their sole business to preserve, sing, and teach these melodies. In the confusion and misery following the downfall of the kingdom of the Goths in the middle of the sixth century the Church became a sanctuary of refuge from the evils of the time. With the revival of religious zeal and the accession of strength the Church flourished, basilicas and convents were multiplied, solemnities increased in number and splendor, and with other liturgic elements the chant expanded. A number of popes in the seventh century were enthusiastic lovers of Church music, and gave it the full benefit of their authority. Among these were Gregory II. and Gregory III., one of whom may have inadvertently given his name to the chant.

The system of tonality upon which the music of the Middle Age was based was the modal or diatonic. The modern system of transposing scales, each major or minor scale containing the same succession of steps and half steps as each of its fellows, dates no further back than the first half of the seventeenth century. The mediaeval system comprises theoretically fourteen, in actual use twelve, distinct modes or keys, known as the ecclesiastical modes or Gregorian modes. These modes are divided into two classes – the “authentic” and “plagal.” The compass of each of the authentic modes lies between the keynote, called the “final,” and the octave above, and includes the notes represented by the white keys of the pianoforte, excluding sharps and flats. The first authentic mode begins on D, the second on E, and so on. Every authentic mode is connected with a mode known as its plagal, which consists of the last four notes of the authentic mode transposed an octave below, and followed by the first five notes of the authentic, the “final” being the same in the two modes. The modes are sometimes transposed a fifth lower or a fourth higher by means of flatting the B. During the epoch of the foundation of the liturgic chant only the first eight modes (four authentic and four plagal) were in use. The first four authentic modes were popularly attributed to St. Ambrose, bishop of Milan in the fourth century, and the first four plagal to St. Gregory, but there is no historic basis for this tradition. The last two modes are a later addition to the system. The Greek names are those by which the modes are popularly known, and indicate a hypothetical connection with the ancient Greek scale system.