полная версия

полная версияOld Boston Taverns and Tavern Clubs

After Braddock’s crushing defeat in the West, a young Virginian colonel, named George Washington, was sent by Governor Dinwiddie to confer with Governor Shirley, who was the great war governor of his day, as Andrew was of our own, with the difference that Shirley then had the general direction of military affairs, from the Ohio to the St. Lawrence, pretty much in his own hands. Colonel Washington took up his quarters at Brackett’s, little imagining, perhaps, that twenty years later he would enter Boston at the head of a victorious republican army, after having quartered his troops in Governor Shirley’s splendid mansion.

Major-General the Marquis Chastellux, of Rochambeau’s auxiliary army, also lodged at the Cromwell’s Head when he was in Boston in 1782. He met there the renowned Paul Jones, whose excessive vanity led him to read to the company in the coffee-room some verses composed in his own honor, it is said, by Lady Craven.

From the tavern of the gentry we pass on to the tavern of the mechanics, and of the class which Abraham Lincoln has forever distinguished by the title of the common people.

Among such houses the Salutation, which stood at the junction of Salutation with North Street, is deserving of a conspicuous place. Its vicinity to the shipyards secured for it the custom of the sturdy North End shipwrights, caulkers, gravers, sparmakers, and the like, – a numerous body, who, while patriots to the backbone, were also quite clannish and independent in their feelings and views, and consequently had to be managed with due regard to their class prejudices, as in politics they always went in a body. Shrewd politicians, like Samuel Adams, understood this. Governor Phips owed his elevation to it. As a body, therefore, these mechanics were extremely formidable, whether at the polls or in carrying out the plans of their leaders. To their meetings the origin of the word caucus is usually referred, the word itself undoubtedly having come into familiar use as a short way of saying caulkers’ meetings.

The Salutation became the point of fusion between leading Whig politicians and the shipwrights. More than sixty influential mechanics attended the first meeting, called in 1772, at which Dr. Warren drew up a code of by-laws. Some leading mechanic, however, was always chosen to be the moderator. The “caucus,” as it began to be called, continued to meet in this place until after the destruction of the tea, when, for greater secrecy, it became advisable to transfer the sittings to another place, and then the Green Dragon, in Union Street, was selected.

The Salutation had a sign of the sort that is said to tickle the popular fancy for what is quaint or humorous. It represented two citizens, with hands extended, bowing and scraping to each other in the most approved fashion. So the North-Enders nicknamed it “The Two Palaverers,” by which name it was most commonly known. This house, also, was a reminiscence of the Salutation in Newgate Street, London, which was the favorite haunt of Lamb and Coleridge.

The Green Dragon will probably outlive all its contemporaries in the popular estimation. In the first place a mural tablet, with a dragon sculptured in relief, has been set in the wall of the building that now stands upon some part of the old tavern site. It is the only one of the old inns to be so distinguished. Its sign was the fabled dragon, in hammered metal, projecting out above the door, and was probably the counterpart of the Green Dragon in Bishopsgate Street, London.

As a public house this one goes back to 1712, when Richard Pullen kept it; and we also find it noticed, in 1715, as a place for entering horses to be run for a piece of plate of the value of twenty-five pounds. In passing, we may as well mention the fact that Revere Beach was the favorite race-ground of that day. The house was well situated for intercepting travel to and from the northern counties.

To resume the historical connection between the Salutation and Green Dragon, its worthy successor, it appears that Dr. Warren continued to be the commanding figure after the change of location; and, if he was not already the popular idol, he certainly came little short of it, for everything pointed to him as the coming leader whom the exigency should raise up. Samuel Adams was popular in a different way. He was cool, far-sighted, and persistent, but he certainly lacked the magnetic quality. Warren was much younger, far more impetuous and aggressive, – in short, he possessed all the more brilliant qualities for leadership which Adams lacked. Moreover, he was a fluent and effective speaker, of graceful person, handsome, affable, with frank and winning manners, all of which added no little to his popularity. Adams inspired respect, Warren confidence. As Adams himself said, he belonged to the “cabinet,” while Warren’s whole make-up as clearly marked him for the field.

In all the local events preliminary to our revolutionary struggle, this Green Dragon section or junto constituted an active and positive force. It represented the muscle of the Revolution. Every member was sworn to secrecy, and of them all one only proved recreant to his oath.

These were the men who gave the alarm on the eve of the battle of Lexington, who spirited away cannon under General Gage’s nose, and who in so many instances gallantly fought in the ranks of the republican army. Wanting a man whom he could fully trust, Warren early singled out Paul Revere for the most important services. He found him as true as steel. A peculiar kind of friendship seems to have sprung up between the two, owing, perhaps, to the same daring spirit common to both. So when Warren sent word to Revere that he must instantly ride to Lexington or all would be lost, he knew that, if it lay in the power of man to do it, the thing would be done.

Besides the more noted of the tavern clubs there were numerous private coteries, some exclusively composed of politicians, others more resembling our modern debating societies than anything else. These clubs usually met at the houses of the members themselves, so exerting a silent influence on the body politic. The non-importation agreement originated at a private club in 1773. But all were not on the patriot side. The crown had equally zealous supporters, who met and talked the situation over without any of the secrecy which prudence counselled the other side to use in regard to their proceedings. Some associations endeavored to hold the balance between the factions by standing neutral. They deprecated the encroachments of the mother-country, but favored passive obedience. Dryden has described them:

“Not Whigs nor Tories they, nor this nor that,Nor birds nor beasts, but just a kind of bat, —A twilight animal, true to neither cause,With Tory wings but Whiggish teeth and claws.”It should be mentioned that Gridley, the father of the Boston Bar, undertook, in 1765, to organize a law club, with the purpose of making head against Otis, Thatcher, and Auchmuty. John Adams and Fitch were Gridley’s best men. They met first at Ballard’s, and subsequently at each other’s chambers; their “sodality,” as they called it, being for professional study and advancement. Gridley, it appears, was a little jealous of his old pupil, Otis, who had beaten him in the famous argument on the Writs of Assistance. Mention is also made of a club of which Daniel Leonard (Massachusettensis), John Lowell, Elisha Hutchinson, Frank Dana, and Josiah Quincy were members. Similar clubs also existed in most of the principal towns in New England.

The Sons of Liberty adopted the name given by Colonel Barré to the enemies of passive obedience in America. They met in the counting-room of Chase and Speakman’s distillery, near Liberty Tree.3 Mackintosh, the man who led the mob in the Stamp Act riots, is doubtless the same person who assisted in throwing the tea overboard. We hear no more of him after this. The “Sons” were an eminently democratic organization, as few except mechanics were members. Among them were men like Avery, Crafts, and Edes the printer. All attained more or less prominence. Edes continued to print the Boston Gazette long after the Revolution. During Bernard’s administration he was offered the whole of the government printing, if he would stop his opposition to the measures of the crown. He refused the bribe, and his paper was the only one printed in America without a stamp, in direct violation of an Act of Parliament. The “Sons” pursued their measures with such vigor as to create much alarm among the loyalists, on whom the Stamp Act riots had made a lasting impression. Samuel Adams is thought to have influenced their proceedings more than any other of the leaders. It was by no means a league of ascetics, who had resolved to mortify the flesh, as punch and tobacco were liberally used to stimulate the deliberations.

No important political association outlived the beginning of hostilities. All the leaders were engaged in the military or civil service on one or the other side. Of the circle that met at the Merchants’ three were members of the Philadelphia Congress of 1774, one was president of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, the career of two was closed by death, and that of Otis by insanity.

IV.

SIGNBOARD HUMOR

Another tavern sign, though of later date, was that of the Good Woman, at the North End. This Good Woman was painted without a head.

Still another board had painted on it a bird, a tree, a ship, and a foaming can, with the legend, —

“This is the bird that never flew,This is the tree which never grew,This is the ship which never sails,This is the can which never fails.”The Dog and Pot, Turk’s Head, Tun and Bacchus, were also old and favorite emblems. Some of the houses which swung these signs were very quaint specimens of our early architecture. So, also, the signs themselves were not unfrequently the work of good artists. Smibert or Copley may have painted some of them. West once offered five hundred dollars for a red lion he had painted for a tavern sign.

Not a few boards displayed a good deal of ingenuity and mother-wit, which was not without its effect, especially upon thirsty Jack, who could hardly be expected to resist such an appeal as this one of the Ship in Distress:

“With sorrows I am compass’d round;Pray lend a hand, my ship’s aground.”We hear of another signboard hanging out at the extreme South End of the town, on which was depicted a globe with a man breaking through the crust, like a chicken from its shell. The man’s nakedness was supposed to betoken extreme poverty.

So much for the sign itself. The story goes that early one morning a continental regiment was halted in front of the tavern, after having just made a forced march from Providence. The men were broken down with fatigue, bespattered with mud, famishing from hunger. One of these veterans doubtless echoed the sentiments of all the rest when he shouted out to the man on the sign, “’List, darn ye! ’List, and you’ll get through this world fast enough!”

In time of war the taverns were favorite recruiting rendezvous. Those at the waterside were conveniently situated for picking up men from among the idlers who frequented the tap-rooms. Under date of 1745, when we were at war with France, bills were posted in the town giving notice to all concerned that, “All gentlemen sailors and others, who are minded to go on a cruise off of Cape Breton, on board the brigantine Hawk, Captain Philip Bass commander, mounting fourteen carriage, and twenty swivel guns, going in consort with the brigantine Ranger, Captain Edward Fryer commander, of the like force, to intercept the East India, South Sea, and other ships bound to Cape Breton, let them repair to the Widow Gray’s at the Crown Tavern, at the head of Clark’s Wharf, to go with Captain Bass, or to the Vernon’s Head, Richard Smith’s, in King Street, to go in the Ranger.” “Gentlemen sailors” is a novel sea-term that must have tickled an old salt’s fancy amazingly.

The following notice, given at the same date in the most public manner, is now curious reading. “To be sold, a likely negro or mulatto boy, about eleven years of age.” This was in Boston.

The Revolution wrought swift and significant change in many of the old, favorite signboards. Though the idea remained the same, their symbolism was now put to a different use. Down came the king’s and up went the people’s arms. The crowns and sceptres, the lions and unicorns, furnished fuel for patriotic bonfires or were painted out forever. With them disappeared the last tokens of the monarchy. The crown was knocked into a cocked-hat, the sceptre fell at the unsheathing of the sword. The heads of Washington and Hancock, Putnam and Lee, Jones and Hopkins, now fired the martial heart instead of Vernon, Hawk, or Wolfe. Allegiance to old and cherished traditions was swept away as ruthlessly as if it were in truth but the reflection of that loyalty which the colonists had now thrown off forever. They had accepted the maxim, that, when a subject draws his sword against his king, he should throw away the scabbard.

Such acts are not to be referred to the fickleness of popular favor which Horace Walpole has moralized upon, or which the poet satirizes in the lines, —

“Vernon, the Butcher Cumberland, Wolfe, Hawke,Prince Ferdinand, Granby, Burgoyne, Keppell, Howe,Evil and good have had their tithe of talk,And filled their sign-post then like Wellesly now.”Rather should we credit it to that genuine and impassioned outburst of patriotic feeling which, having turned royalty out of doors, indignantly tossed its worthless trappings into the street after it.

Not a single specimen of the old-time hostelries now remains in Boston. All is changed. The demon demolition is everywhere. Does not this very want of permanence suggest, with much force, the need of perpetuating a noted house or site by some appropriate memorial? It is true that a beginning has been made in this direction, but much more remains to be done. In this way, a great deal of curious and valuable information may be picked up in the streets, as all who run may read. It has been noticed that very few pass by such memorials without stopping to read the inscriptions. Certainly, no more popular method of teaching history could well be devised. This being done, on a liberal scale, the city would still hold its antique flavor through the records everywhere displayed on the walls of its buildings, and we should have a home application of the couplet:

“Oh, but a wit can study in the streets,And raise his mind above the mob he meets.”APPENDIX.

BOSTON TAVERNS TO THE YEAR 1800

The Anchor, or Blue Anchor. Robert Turner, vintner, came into possession of the estate (Richard Fairbanks’s) in 1652, died in 1664, and was succeeded in the business by his son John, who continued it till his own death in 1681; Turner’s widow married George Monck, or Monk, who kept the Anchor until his decease in 1698; his widow carried on the business till 1703, when the estate probably ceased to be a tavern. The house was destroyed in the great fire of 1711. The old and new Globe buildings stand on the site. [See communication of William R. Bagnall in Boston Daily Globe of April 2, 1885.] Committees of the General Court used to meet here. (Hutchinson Coll., 345, 347.)

Admiral Vernon, or Vernon’s Head, corner of State Street and Merchants’ Row. In 1743, Peter Faneuil’s warehouse was opposite. Richard Smith kept it in 1745, Mary Bean in 1775; its sign was a portrait of the admiral.

American Coffee-House. See British Coffee-House.

Black Horse, in Prince Street, formerly Black Horse Lane, so named from the tavern as early as 1698.

Brazen-Head. In Old Cornhill. Though not a tavern, memorable as the place where the Great Fire of 1760 originated.

Bull, lower end of Summer Street, north side; demolished 1833 to make room “for the new street from Sea to Broad,” formerly Flounder Lane, now Atlantic Avenue. It was then a very old building. Bull’s Wharf and Lane named for it.

British Coffee-House, mentioned in 1762. John Ballard kept it. Cord Cordis, in 1771.

Bunch of Grapes. Kept by Francis Holmes, 1712; William Coffin, 1731-33; Edward Lutwych, 1733; Joshua Barker, 1749; William Wetherhead, 1750; Rebecca Coffin, 1760; Joseph Ingersoll, 1764-72. [In 1768 Ingersoll also had a wine-cellar next door.] Captain John Marston was landlord 1775-78; William Foster, 1782; Colonel Dudley Colman, 1783; James Vila, 1789, in which year he removed to Concert Hall; Thomas Lobdell, 1789. Trinity Church was organized in this house. It was often described as being at the head of Long Wharf.

Castle Tavern, afterward the George Tavern. Northeast by Wing’s Lane (Elm Street), front or southeast by Dock Square. For an account of Hudson’s marital troubles, see Winthrop’s New England, II. 249. Another house of the same name is mentioned in 1675 and 1693. A still earlier name was the “Blew Bell,” 1673. It was in Mackerel Lane (Kilby Street), corner of Liberty Square.

Cole’s Inn. See the referred-to deed in Proc. Am. Ant. Soc., VII. p. 51. For the episode of Lord Leigh consult Old Landmarks of Boston, p. 109.

Cromwell’s Head, by Anthony Brackett, 1760; by his widow, 1764-68; later by Joshua Brackett. A two-story wooden house advertised to be sold, 1802.

Crown Coffee-House. First house on Long Wharf. Thomas Selby kept it 1718-24; Widow Anna Swords, 1749; then the property of Governor Belcher; Belcher sold to Richard Smith, innholder, who in 1751 sold to Robert Sherlock.

Crown Tavern. Widow Day’s, head of Clark’s Wharf; rendezvous for privateersmen in 1745.

Cross Tavern, corner of Cross and Ann Streets, 1732; Samuel Mattocks advertises, 1729, two young bears “very tame” for sale at the Sign of the Cross. Cross Street takes its name from the tavern. Perhaps the same as the Red Cross, in Ann Street, mentioned in 1746, and then kept by John Osborn. Men who had enlisted for the Canada expedition were ordered to report there.

Dog and Pot, at the head of Bartlett’s Wharf in Ann (North) Street, or, as then described, Fish Street. Bartlett’s Wharf was in 1722 next northeast of Lee’s shipyard.

Concert Hall was not at first a public house, but was built for, and mostly used as, a place for giving musical entertainments, balls, parties, etc., though refreshments were probably served in it by the lessee. A “concert of musick” was advertised to be given there as early as 1755. (See Landmarks of Boston.) Thomas Turner had a dancing and fencing academy there in 1776. As has been mentioned, James Vila took charge of Concert Hall in 1789. The old hall, which formed the second story, was high enough to be divided into two stories when the building was altered by later owners. It was of brick, and had two ornamental scrolls on the front, which were removed when the alterations were made.

Great Britain Coffee-House, Ann Street, 1715. The house of Mr. Daniel Stevens, Ann Street, near the drawbridge. There was another house of the same name in Queen (Court) Street, near the Exchange, in 1713, where “superfine bohea, and green tea, chocolate, coffee-powder, etc.,” were advertised.

George, or St. George, Tavern, on the Neck, near Roxbury line. (See Landmarks of Boston.) Noted as early as 1721. Simon Rogers kept it 1730-34. In 1769 Edward Bardin took it and changed the name to the King’s Arms. Thomas Brackett was landlord in 1770. Samuel Mears, later. During the siege of 1775 the tavern was burnt by the British, as it covered our advanced line. It was known at that time by its old name of the George.

Golden Ball. Loring’s Tavern, Merchants’ Row, corner of Corn Court, 1777. Kept by Mrs. Loring in 1789.

General Wolfe, Town Dock, north side of Faneuil Hall, 1768. Elizabeth Coleman offers for sale utensils of Brew-House, etc., 1773.

Green Dragon, also Freemason’s Arms. By Richard Pullin, 1712; by Mr. Pattoun, 1715; Joseph Kilder, 1734, who came from the Three Cranes, Charlestown. John Cary was licensed to keep it in 1769; Benjamin Burdick, 1771, when it became the place of meeting of the Revolutionary Club. St. Andrews Lodge of Freemasons bought the building before the Revolution, and continued to own it for more than a century. See p. 46.

Hancock House, Corn Court; sign has Governor Hancock’s portrait, – a wretched daub; said to have been the house in which Louis Philippe lodged during his short stay in Boston.

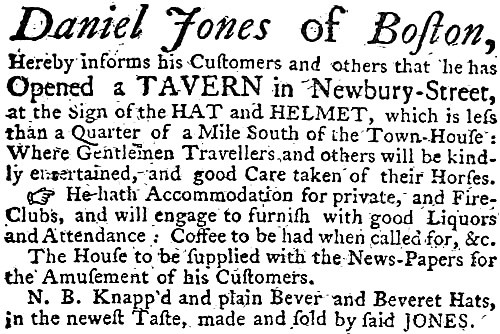

Hat and Helmet, by Daniel Jones; less than a quarter of a mile south of the Town-House.

Indian Queen, Blue Bell, and – stood on the site of the Parker Block, Washington Street, formerly Marlborough Street. Nathaniel Bishop kept it in 1673. After stages begun running into the country, this house, then kept by Zadock Pomeroy, was a regular starting-place for the Concord, Groton, and Leominster stages. It was succeeded by the Washington Coffee-House. The Indian Queen, in Bromfield Street, was another noted stage-house, though not of so early date. Isaac Trask, Nabby, his widow, Simeon Boyden, and Preston Shepard kept it. The Bromfield House succeeded it, on the Methodist Book Concern site.

BOSTON NEWS-LETTER, FEB. 15, 1770

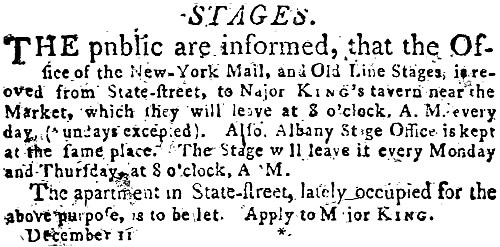

COLUMBIAN CENTINEL. DEC. 11, 1799

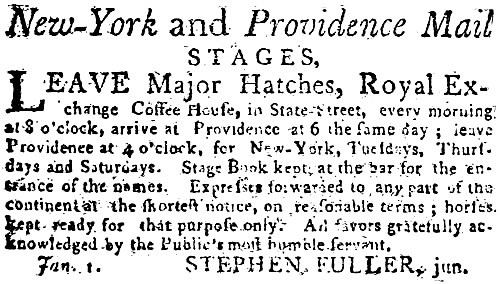

COLUMBIAN CENTINEL, JAN. 1, 1800

Julien’s Restorator, corner of Congress and Milk streets. One of the most ancient buildings in Boston, when taken down in 1824, it having escaped the great fire of 1759. It stood in a grass-plot, fenced in from the street. It was a private dwelling until 1794. Then Jean Baptiste Julien opened in it the first public eating-house to be established in Boston, with the distinctive title of “Restorator,” – a crude attempt to turn the French word restaurant into English. Before this time such places had always been called cook-shops. Julien was a Frenchman, who, like many of his countrymen, took refuge in America during the Reign of Terror. His soups soon became famous among the gourmands of the town, while the novelty of his cuisine attracted custom. He was familiarly nicknamed the “Prince of Soups.” At Julien’s death, in 1805, his widow succeeded him in the business, she carrying it on successfully for ten years. The following lines were addressed to her successor, Frederick Rouillard:

JULIEN’S RESTORATORI knew by the glow that so rosily shoneUpon Frederick’s cheeks, that he lived on good cheer;And I said, “If there’s steaks to be had in the town,The man who loves venison should look for them here.”’Twas two; and the dinners were smoking around,The cits hastened home at the savory smell,And so still was the street that I heard not a soundBut the barkeeper ringing the Coffee-House bell.“And here in the cosy Old Club,”4 I exclaimed,“With a steak that was tender, and Frederick’s best wine,While under my platter a spirit-blaze flamed,How long could I sit, and how well could I dine!“By the side of my venison a tumbler of beerOr a bottle of sherry how pleasant to see,And to know that I dined on the best of the deer,That never was dearer to any than me!”King’s Head, by Scarlet’s Wharf (northwest corner Fleet and North streets); burnt 1691, and rebuilt. Fleet Street was formerly Scarlet’s Wharf Lane. Kept by James Davenport, 1755, and probably, also, by his widow. “A maiden dwarf, fifty-two years old,” and only twenty-two inches high, was “to be seen at Widow Bignall’s,” next door to the King’s Head, in August, 1771. The old King’s Head, in Chancery Lane, London, was the rendezvous of Titus Oates’ party. Cowley the poet was born in it.