Полная версия

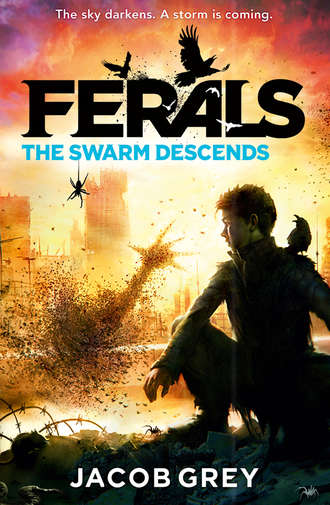

The Swarm Descends

There were about a dozen people present besides Crumb, himself and Pip. Caw recognised a few of the other ferals. There was Ali, dressed in a slim-fitting black suit and still clutching his briefcase, which buzzed softly with the swarm of bees held inside. Racklen, the hulking wolf feral, stood at his side. Caw was disappointed not to see Madeleine, the raven-haired girl in the wheelchair, but he saw two of her squirrels perched in the branches at the edge of the graveyard.

He tried to scan the other faces without staring. There were people of every age. A girl of maybe four or five had a huge Dobermann sitting patiently at her side. An old man was leaning on a stick, though he didn’t seem to be accompanied by any creature. Two boys, who looked identical, stood on either side of a large, floppy-eared hare, its nose twitching. At the back stood a youngish couple with a baby in a pram. A hawk sat perched on the pram’s rim, and beside it, strangely, was a raccoon. Were both parents ferals?

At the head of the grave stood a figure Caw knew very well indeed. Mrs Strickham was dressed in a long black coat with pale gleaming buttons. She looked more severe than he remembered her from two months ago, the lines of her face taut. She acknowledged Caw with a brief nod and a smile that softened her features. She was holding a white rose. “Please, everyone, gather around,” she said.

Caw joined the group, which formed a ring around the empty grave.

No one spoke for several seconds. Caw had never been to a funeral before, let alone a feral one. He wasn’t sure what was supposed to happen. Then he noticed that, one by one, the crowd were turning towards the church. He followed their gaze, up the path, and his eyes fell on the strangest thing.

Not the coffin itself – that was a simple casket, made of tightly woven wicker – but the fact that it was moving, gliding across the uneven ground as if on a cushion of air. Caw suddenly realised what he was seeing. There were centipedes under the coffin, thousands of them, their tiny legs scurrying along.

“They’re carrying her!” he murmured.

“It’s their final duty,” said Crumb.

When they reached the graveside, the centipedes descended the slope down into the earth, taking the coffin with them. As it came to rest at the bottom, Mrs Strickham cleared her throat.

“Thank you all for coming,” she said, speaking over the grave. “Emily would have been honoured to see you here.” Several heads bobbed in acknowledgement. Not for the first time, Caw felt a stranger in the company of the ferals and the history they shared.

“I first met Emily fifteen years ago,” Velma Strickham continued. “Some of you are too young to remember a time before the Dark Summer, when many of our kind were known to one another.” A smile crept over Mrs Strickham’s face as she said the words. “Emily ran a ferals group under the guise of a knitting circle, and many struggling with their powers benefited from her kindness and advice. She was a loving mother to her three girls as well. I say this from personal experience, but it is always hard to know when as a feral parent you should tell your children.” She paused. “When to burden them with their destiny.”

Caw swallowed as a fresh pang of grief rose from his heart. His mother was snatched away before she ever had the chance to speak with him.

His hand stroked the stone in his pocket again and he felt suddenly empty. There was a lot his mother hadn’t told him. He looked around the assembled faces. Surely someone here must know about the stone? But could he really trust them? The words of Quaker flashed through his mind.

Tell no one you have it. Not Crumb, not Lydia, not Velma – no one.

Crumb put his arm around Caw’s shoulder, as if he sensed his discomfort, and Caw let his fingers release the stone.

“Emily was preparing to tell her children about her powers when the Dark Summer fell upon us,” said Mrs Strickham. “You all suffered in those months. We lost many. But few suffered as Emily did.”

The air seemed to have become chillier as a light wind picked up, ruffling the treetops and blowing leaves across the graveyard. Caw saw more birds gathered in the branches – thrushes, woodpeckers, and an owl. All seemed to be watching intently. The old man with the stick shifted a little, and a ferret poked its head from the bottom of his trouser leg.

“Mamba’s snakes were trying to find Emily herself, but instead they found her daughters,” Mrs Strickham said, her voice close to cracking. “Their deaths were quick and that was a small mercy. After that Emily fought on, somehow. Without her, we could never have defeated our enemies during the Dark Summer. But it took all she had and afterwards she was never the same.

“I will not say her twilight years were happy, because we do not need to sugarcoat our existence, and Emily would be contemptuous of such a lie. But nor do I think she died a wretched death. In fact, she told me just a week ago that she was planning to set up her knitting circle once more. That can only mean she had found a sort of peace.”

Mrs Strickham paused. Caw searched the faces of the other mourners, and saw that several were in tears.

“With Emily, the centipede line ends,” said Mrs Strickham. “Hers is a double death, and our world is poorer for her passing. May she rest in peace.”

“Rest in peace,” the crowd muttered, and Caw joined in.

Mrs Strickham threw the rose on to the coffin. Racklen stepped forward and began to shovel earth into the grave. The centipedes, Caw noticed, remained in the ground with their mistress.

“You went to see Quaker, didn’t you?”

The question startled Caw. He whipped his head around to see Pip, then turned back to keep his eyes on Mrs Strickham.

“You followed me!” he whispered.

“You might have got away from the pigeons, but mice can crawl down drains,” said Pip. “We lost track of you when you went up a ladder though.”

Caw let out a silent sigh of relief. The last thing he needed was Crumb finding out about the incident with the police car. He would definitely not approve.

The mourners were beginning to drift away now and Crumb had gone over to speak with the ferret feral, greeting him with a hug. Pip’s mice were scampering around with the raccoon, climbing its fur while it tried to shake them off. Ali’s bees flew lazily around the meadow flowers that lined the graveyard, while their master spoke to the girl with the Dobermann.

“So what did you want with Quaker?” asked Pip. “Don’t worry, I haven’t told Crumb.”

“Do whatever you like,” said Caw. “I just wanted to ask him more about my parents.”

Pip frowned. But before the mouse feral could ask any more questions, Crumb beckoned them over. “You two, come and say hello to Mr Duddle.”

Pip did as he was told without question, but Caw hung back. Why did Crumb have to boss him around all the time? He pretended he hadn’t heard, he went over to the wolf feral instead, who was still shovelling, sweat glistening on his forehead.

The huge man paused as Caw came close and buried the shovel in the ground. “Crow talker,” he said flatly.

Caw wasn’t really sure how to respond. The wolf feral didn’t seem about to carry on digging, but didn’t say anything either. Caw began to wish he’d gone with Pip.

“I just wanted to ask,” Caw said slowly, “about the girl who talks to squirrels. Is she all right?” Caw remembered Racklen was the one pushing Madeleine’s wheelchair that day when he’d first met them.

“Why are you asking me?” rumbled the wolf feral.

Caw shrank back a little. “I … I thought you might be friends,” he said.

Something brushed against Caw’s leg, and when he looked down he saw that it was a fox. Velma Strickham was standing a few paces behind, staring fiercely at Caw.

“Would you come with me a moment please?” she asked. “There’s someone who’d like to say hello.” Without waiting, she turned and headed down the path through the graveyard.

“I guess I should go,” Caw mumbled at Racklen. “I’m sorry.”

The wolf feral’s glare softened, and he shook his head. “No, crow talker,” he said quietly. “I am sorry. Emily was a friend of mine, and today has been hard. Madeleine has a hospital appointment today, but she is doing well.”

Caw nodded.

“And by the way,” said Racklen, “all ferals owe you their thanks. What you did in the Land of the Dead … it was very brave.”

He thrust out a huge, soil-stained paw of a hand. Caw took it, blushing, then ran down the hill after Mrs Strickham. She had already reached her car and opened the door.

Lydia stepped out. Her mass of red hair was loose over her shoulders and her fringe came right to her eyeline, making her delicate face seem even smaller than normal. She was wearing jeans and a long-sleeved T-shirt with a picture of a seal reclining on an iceberg. He studied the words for a moment. It read “Just Chill”. He looked up to see that his friend was beaming at him.

Caw rushed up to her, grinning, then wasn’t sure exactly what to do. She opened her arms and Caw realised she wanted to give him a hug. He leant forward and let her do it, wrapping his arms awkwardly around her. She squeezed him tightly.

“I haven’t seen you for ages,” Lydia said.

Caw shot a glance at Mrs Strickham. Her attention was on the churchyard, but he sensed she was listening to everything he said.

“No,” Caw replied. “I’ve been … erm … busy.”

“Still living at the church?”

Caw nodded. “What’s been happening with you?”

Lydia blew out her cheeks. “A lot, I guess.” She looked across, waiting until her mother had climbed into the car and closed the door. She lowered her voice. “Caw, it’s been terrible! Mum hardly lets me out of the house. I think she’s worried I’ll get into trouble. And Dad’s lost his job.”

“Oh no! Why?” said Caw.

Lydia shrugged. “Supposedly because of the escaped convicts,” said Lydia. “But Dad says it’s political. Something to do with a new Police Commissioner wanting to replace the governor at the prison. We might have to move out of the house. But anyway …” she punched his arm. “You’ve been so busy you couldn’t come and see me?”

Caw could tell she was upset. “We need to get going,” said Lydia’s mother impatiently, hand on the car roof.

“Crumb’s been training me really hard,” said Caw, and he knew at once how lame it sounded. He rolled up his sleeve and showed her his bruises from where Crumb’s pigeons had shoved him over a park bench two days before. There were several others too from the fall off the police car – grazes and a deep purple welt across his wrist.

“Ouch!” she said. “Did you do something to upset him?”

“It’s worse than it looks,” Caw said guiltily. “He’s been teaching me to read too. There’s still lots of words I don’t know, but I’m getting there.”

“That’s great!” said Lydia, though a cloud passed across her face as she spoke. “And how are Screech and Glum?”

“The same,” said Caw. “Well, not quite. I’ve got a new one called Shimmer. She’s cool. Screech really likes her.”

Lydia giggled. “You mean he has a crush.”

I do not! croaked a voice from above. Caw saw Screech was perched on the branch of an elm tree. I just admire her flying ability.

The car’s engine started up. Mrs Strickham had climbed in and shut the door.

“We went to my old house yesterday,” said Caw. “And guess what – we found a girl living there!”

“Oh?” said Lydia, with a small grimace. “What, like squatting?”

“I guess so,” said Caw. “Her name’s Selina. She’s homeless, like I was. I’m going to teach her to scavenge.”

“That’s … that’s cool, Caw,” said Lydia. “Maybe I can come too?”

Caw hadn’t been expecting that. “Why would you want to scavenge? You’ve got proper food, y’know – on a plate.”

“Because it’s fun,” said Lydia. “When are you heading out?”

“Er … I don’t know,” said Caw. “Look, Lydia, maybe it’s best if you don’t. It might not be safe.”

She frowned. “I can look after myself.”

“Last time you got mixed up with me, I almost got you killed,” said Caw.

The stone weighed heavy in his pocket. The dangers of the past might be behind him, but new ones lingered in waiting, he was sure. Until he knew what the stone was, and why Quaker was so scared of it, he couldn’t risk letting Lydia get close again.

The car window opened, and Mrs Strickham’s face appeared. “We need to go now, Lydia. Your father will get suspicious if we’re out shopping much longer.”

“I’m sorry,” said Caw. “I just don’t want to get you into trouble.”

“Come on, sweetheart,” said her mother.

Lydia bit her bottom lip. “Caw, I thought we were friends,” she said.

He blinked at her sudden fierce tone. They’d certainly been through a lot together, but he’d never really had friends, apart from the crows. “We … we are,” he said.

She turned away and opened the car door, climbing inside. As she fastened her seatbelt she shook her head sadly. “Then why don’t you act like it?”

The door slammed before Caw could answer and the car sped off, leaving him standing alone at the edge of the graveyard.

She looked taller tonight, maybe even taller than him, but then he realised she was wearing stacked boots, made of leather and laced up to her ankles. The rest of her clothes were black too, with a knee-length skirt over dark tights and a fitted black jacket zipped up to her chin. He wondered what Lydia would have made of her. She had headphones in her ears and took them out as he approached.

“You’re late,” she said.

Caw pulled out his watch and checked. It was ten past ten. “Sorry,” he said. “There were a ton of police patrols about tonight. I had to come the long way.”

“You’re supposed to put that round your wrist, you know,” she said, pointing at the watch. “Anyway, what’s wrong with the police? You in trouble or something?”

Caw blushed. “It’s not that. I just …” he didn’t know how to finish.

“It’s fine,” she said quickly. “Actually, I wasn’t sure you’d come at all.” She blew into her hands, which were encased in fingerless gloves.

“I said I would. Ready to go?”

“Sure,” she said. “Where d’you take a girl for dinner round here?”

Caw tried not to blush even deeper, but from the heat rising behind his cheeks he knew he had failed miserably. Surely she wasn’t expecting a restaurant. “We’re just scavenging,” he said.

“And I was only joking,” she said. “Tell you what, you show me where to find a good meal, and I’ll work on your sense of humour radar.”

Caw grinned. He knew she was mocking him, but he didn’t mind. “Are you hungry?”

“Always,” said Selina.

“I know a good Chinese place,” said Caw. “They have a really nice table out back by the bins.”

Selina frowned.

“That was a joke too,” said Caw.

Selina clapped. “Oh, right! You’re learning. It sounds divine!”

They set off down the street. Out of habit, Caw stuck to the shadows where he could, but Selina didn’t look worried. She moved with a spring in her step, sometimes straying into the middle of the deserted roads or kicking cans along the street. While Caw’s head jerked at every sound the city made – a far-off dog barking, the revving of a motorbike engine – Selina didn’t even seem to notice them.

They soon reached an area littered with building machinery and cranes. It had been a forgotten construction site for as long as Caw could remember, probably abandoned in the aftermath of the Dark Summer. Caw took off his jacket and laid it over the barbed wire at the top of a fence.

“This is the quickest way into the city centre,” he said, hoisting himself to the top. Straddling the fence, he reached down to Selina.

He needn’t have bothered. “I’m fine, thanks,” she said, ignoring the hand and scampering up. She swung her body over the top, then dropped into a crouch on the other side. “So where did you say you lived again?” she asked.

Caw climbed down as well. “Er … I didn’t,” he said. “I move around.”

Caw didn’t want to keep secrets from her – but he still wasn’t ready to tell her about the church. And he was grateful that Selina didn’t push it. He remembered when he’d first met Lydia, and she’d bombarded him with questions.

“I used to live in a tree-house,” he said.

“No way!” she replied. “Where?”

“In the old park, north of here,” said Caw.

“That place is creepy!” said Selina.

“I kind of liked it.” Caw remembered the place fondly now, but in the winter it had sometimes got so cold there was frost on his blanket in the morning. “How are you with heights?” he asked. “The safest way is over the rooftops from here.”

Selina swatted an insect off her shoulder, looking up at the buildings ahead. “I’ll give it a try,” she said.

Caw went first, placing his feet and hands in the cracked mortar and climbing up to a broken first-floor window. This place had been a military barracks, Crumb had told him. Selina made it up easily. Caw was glad he hadn’t invited Lydia – she would have slowed them down. They crossed a long room littered with old papers, then climbed two sets of stairs to the roof fire escape. As they came through, the city spread out beyond.

“Oh, wow!” said Selina.

Caw saw the wonder in her face and felt a rush of pride. This was one of his favourite views as well. He set off at a light jog and Selina followed.

“There’s a jump coming up,” he said. “Not big, but follow my lead.”

He reached the edge of the building and launched himself over the two-metre gap. Then he turned to watch Selina, but she had already jumped, landing neatly beside him.

“You’re a natural,” he said, impressed.

“I take – I took – gymnastics at school,” she said, “before I ran away. It’s cool up here! It’s like being a bird, looking down on everything.”

Caw instinctively checked the sky, surprised that until then he hadn’t thought about his crows at all. He saw Shimmer and Screech sitting on an aerial about twenty metres to his left. Glum would be nearby too. They were keeping their distance.

They continued across the rooftops and Selina didn’t put a foot wrong. Gradually they penetrated closer to the heart of the city.

“So, do you miss school?” Caw asked.

“Er … sure,” said Selina. “Well, I miss my friends.”

“How long have you been away from home?”

He checked her expression to make sure he wasn’t being too nosey, but she looked fine.

“A couple of months,” she said. “I didn’t think I’d be gone this long, really. I just wanted to be on my own for a while at first, but then … well, I found I quite liked it.”

Caw paused at the edge of a building, peering into the road below. He came this way because most of the shops were boarded up and the streetlights were never switched on, but there were still cars about, and a few people.

“So how’ve you got by?” he said. “For food and stuff like that?”

“It’s been hard at times,” she replied. “I begged a bit in the city, did some things I shouldn’t.”

“What do you mean?” asked Caw, nervously.

“Oh, nothing too bad,” she said. “I learnt how to survive, that’s all.”

Caw was glad to let the subject drop. “We have to climb down here,” he said. “There’s a network of alleys that leads to the river – that’s where the restaurant is.” He pointed to a drainpipe. “You OK with that?”

Selina nodded. She touched his arm. “Wait, Caw – I want to ask you something.”

“Yes?”

She paused. “Tell me if it’s none of my business, but … you said that house was yours. Where are your parents?”

“Dead,” Caw replied. “A long time ago.”

“Oh,” said Selina. “I’m sorry.” Again, she didn’t pursue it.

“That’s all right,” said Caw, shrugging. “What about your folks? Why’d you run away?”

Selina’s mouth twisted a little. “My dad walked out before I was born,” she said. “Mum and I have never really got along. She’s got a really important job. Works ridiculous hours. Probably hasn’t even noticed I’m gone.” She smiled. Unconvincingly, Caw thought.

“Do you think you’ll ever go back?” he asked.

Selina lowered herself over the edge of the building, gripping the drainpipe in both hands.

“I don’t know,” she said.

She slid down quickly, and Caw followed.

Struggling to keep up? said Shimmer, tip-toeing along the parapet of the building.

“A bit,” Caw muttered, as he landed beside Selina.

“D’you always talk to yourself?” she asked.

Caw pasted on a grin. “Sometimes – sorry.”

Soon they reached the river, where the giant wharves stood like hulking silhouettes. Caw had never liked the Blackwater. Perhaps it was simply because he couldn’t swim, but there was something about the impenetrable darkness of the water too, like a black abyss. Crumb told him it was so dirty that if you drank a single mouthful, you’d die within a day. He said there were stories in the Blackstone Herald about people falling in and never being seen again. Caw didn’t doubt it. He remembered Miss Wallace giving him a book once about a creature with a woman’s body and a fish’s tail that lived in the river. The water had looked blue though, rather than black and full of filth. As they walked the deserted path that ran alongside the river, he wondered if there were ferals who could talk to fish.

“You OK?” asked Selina.

Caw nodded. She was at his side, looking at him curiously.

There were boats of various sizes moored up – most looked completely abandoned, like floating carcasses butting up against the dockside. Some had names like Fair Maiden, or The Floating Rose, which seemed completely at odds with their peeling paint, or the years’ worth of weed growing up their battered hulls.

One boat, in better repair than most, was unmarked. It had a slightly sunken cabin positioned in the middle of the craft and through a glass window Caw saw a cabin piled with crates and boxes.

“Maybe we’ll find something in there,” said Selina, pointing.

Caw looked up and down the bank nervously. He couldn’t see anyone – the nearest bridge was some distance away, where cars trailed across like streaks of light.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Isn’t that stealing?”

Selina shrugged. “I guess so. Seriously, have you never taken anything before?”

Caw blushed. “Yes,” he said. When he’d been younger and more desperate. Clothes off people’s washing lines, bread from an open truck. But this seemed different. He had other ways to survive.

Selina reached into her pocket and took out something glinting on a leather strap. Caw’s eyes widened and he felt automatically inside his coat. “My watch! How did you –”

Selina gave a crooked grin. “Up there on the roof, when I touched your arm.”

Caw was impressed, and a tiny bit annoyed. “I didn’t even feel it,” he said.

“Well, that’s all I meant when I said I’ve learnt to survive,” she said. “I never took anything off people who’d really suffer.” She handed Caw back the watch and he tucked it deep inside his coat pocket.

“Come on,” urged Selina. “No one will notice – we won’t take much. Plus we don’t have to go all the way into the city.”

She was right, sort of, thought Caw. But it still didn’t feel good. He looked around again and saw the three crows had alighted nearby on another boat’s roof. Caw knew they would side with Selina. Crows didn’t have a lot of time for the finer points of human morals. He wondered what Lydia would say though.