полная версия

полная версияThe History of Salt

Next to muscle, cartilage contains the largest amount of the chloride of sodium, and this especially in the temporary cartilages of the fœtus, its place being taken by the phosphate of lime as it approaches the time of birth. The percentage of the chloride of sodium contained in the ash of the costal cartilage of an adult is about 8·2; in the laryngeal cartilage 11·2; but as the ash does not constitute above 3·4 per cent. of the entire substance the percentage of the chloride of sodium in the latter is, at the most, 0·38 of the whole, or less than that of blood and muscle. Only from 0·7 to 1·5 per cent. could be extracted from the ash of bone.

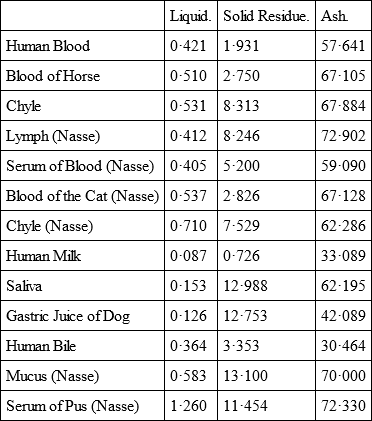

Besides the important uses of the chloride of sodium in the blood to which we have already adverted, it serves the purpose of furnishing the hydrochloric acid required (by many animals, at least) for the gastric secretion; and it likewise supplies the soda-base for the alkaline phosphate, whose presence in the blood appears to serve a most important purpose in the respiratory process. Moreover, there is reason to think, from the experiments of Boussingault upon animals, as well as from other considerations, that the presence of salt in the blood and excreted fluids facilitates the deportation of excrementitious substances from the blood. The proportion in which it occurs in the principal animal fluids is represented by the following table, constructed by Lehmann chiefly from his own analyses; it is highly interesting, and shows us at a glance that it is more important in the economy than any other substance, and is significant of the fact that health cannot exist long if the chloride of sodium is below the normal amount.

Percentage of Chloride of Sodium in various Animal Fluids, their Solid Residue and their Ash.

We have thus proved physiologically that the chloride of sodium holds a most prominent position among the other constituents of the body; that it is present in considerable quantities in muscle as well as in the blood; and that it furnishes the acid, which is necessary for the stomach to perform its functions of digestion. It holds the albumen partly in solution, and its coagulation is dependent more or less on the amount of salt which is present in the blood, and it also possesses the power of preventing the coagulation of the fibrine. In fevers the blood is generally thicker, and has a tendency to coagulate by reason of the partial absence of salt, because a good deal passes off with the perspiration; and fever patients always prefer salt to sugar, for while one refreshes them and helps to restore the usual healthy tone of the palate, by constringing the papillæ of the tongue, the other raises feelings of disgust.

It is also present in cartilage, though in a lesser degree than in blood or muscle, because in cartilage there is no disintegration or waste of tissue, and therefore it does not require such a perpetual supply; there is, on the contrary, a continual loss going on in muscle, especially during exertion. Perspiration is to a certain extent the principal medium which carries off the chloride of sodium, owing to its being held in solution by the liquor-sanguinis; during fatigue, particularly if prolonged, a greater quantity passes off, producing various degrees of thirst. That the normal proportion of the chloride of sodium should be regularly maintained must be obvious.

In febrile disease the fibrine of the blood is materially increased, and there is also a marked decrease of salt, which is dependent on a greater or lesser intensity of the attack, rendering the blood denser, owing to the fact of the tendency of the fibrine to coagulate by reason of the diminution of the chloride of sodium, causing the blood to circulate slowly and with difficulty.

In some other morbid conditions, which we have already noticed, the blood becomes thinner and poorer; and consequently the system degenerates, and we get an anæmic, or chlorotic tendency, especially if there is a scrofulous diathesis. There are other blood diseases, as the reader may suppose, and which are more truly such, than those to which I have just alluded, into the phenomena of which it is not necessary to enter.

In health what a decided difference! the specific gravity of the blood is uniformly equable;58 it circulates with comparative ease; and the whole system is permeated with the life-giving and health-preserving chloride of sodium, and the coagulation of the fibrine is prevented by nothing else but that mineral and inorganic substance – salt, which at the same time purifies and maintains the equalisation of the constituents of the blood. By it also the hydrochloric acid is supplied to the stomach, enabling that organ to perform its functions of digestion in accordance with the laws of health; and it likewise furnishes the alkaline phosphate “whose presence in the blood appears to serve the most important purpose in the respiratory process.”

What stronger evidence do we require to prove the salutary efficacy of salt? No wonder that it is so frequently reverted to in Holy Writ; neither can it be a source of surprise that it has been so carefully cherished and extensively utilised from time immemorial. What is to be regarded as an extraordinary anomaly is that there are not a few who are entire strangers to its virtues, and who prefer impurity and defilement to the luxury of health and cleanliness.

Those who desire more conclusive proof of the utility of salt, of its necessity in the animal economy, and of the peculiar morbid phenomena to which its absence in the system gives rise, I would refer to two articles which appeared at different times in the Medical Press and Circular, and in the Medical Times and Gazette.59 The cases I there mention occurred in different localities, and they demonstrate incontestably that parasites, especially the lumbrici (the tæniæ are well known to infest adults of impure habit), are sometimes the origin of strange and incomprehensible symptoms of a deceptive character, rendering diagnosis extremely difficult and unsatisfactory, and frequently endangering the lives of the sufferers. Is it not a blessing to know that nature has munificently provided a means whereby these distressing evils may be checked and definitely eradicated by a daily use of such an enemy to, and destroyer of, disease as the chloride of sodium, universally known as common salt?

CHAPTER IX

CONCLUSION

It is invariably a relief when one’s task is completed, and more so when it is self-imposed. Putting our thoughts and opinions upon paper for others to peruse and to criticise, is pleasure combined with not a little anxiety; for one cannot with any degree of certainty predict what kind of reception one’s efforts may have from the public, who are frequently led to a choice of books on the recommendation of critics and reviewers; so that an unknown author is placed at a great disadvantage, and at the mercy of those who may laud a book to the skies if they please, satirically criticise another, and pass over a third with a sarcastic smile or a significant shrug of the shoulders. I am afraid that my little volume will unfortunately be found amongst the latter, but I candidly acknowledge that I hope it will be regarded as belonging to the first, or at least to the second.

As I have simply written it in order to point out the virtues of an aliment of the greatest interest in whatever light we may look at it, I trust that if I have not instructed, I have at any rate afforded pleasure to those who have thought it worth their while to glance over its pages; and I shall be quite contented if they have derived as much satisfaction in reading, as I have experienced in writing it.

I have tried to impress upon the reader the advisability, and indeed the necessity, of using the bountiful gifts of nature in a manner consistent with common sense, and not to follow blindly and credulously the whims and conceits of others, but to regard their frantic efforts to indoctrinate the thoughtless, with that dispassionate indifference which is the sign of philosophical complacency and superiority. Lucretius says truly that “nothing is more delightful than to occupy the elevated temples of the wise, well fortified by tranquil learning, whence you may look down upon others and see them straying in every direction, and wandering in search of the path of life.”

Approbation is pleasing, and particularly so when it comes from those who are more able to judge impartially and correctly than others; and censure, if deserved, though far from gratifying, is not of a nature to intimidate or to create discouragement.

With these concluding remarks, and certain misgivings, I now submit my short work to the indulgent consideration of those who read for the sake of obtaining information, those who read for amusement only, and to those who peruse literary productions with the eye of criticism. Lord Bacon advises us to “Read, not to contradict and confute, nor to believe and take for granted, nor to find talk and discourse, but to weigh and consider. Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested. That is, some books are to be read only in parts; others to be read, but not curiously; and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention.”

In conclusion, I must say that I sincerely hope that the candid reader has reaped improvement where the critic may have found only matter for censure.

APPENDIX

A., page 38. “Occasionally lakes are found which have streams flowing into them, but none flowing out. Such lakes are usually salt. The Caspian Sea in Asia is an example. It is called a sea from its great extent, but it is in reality an inland lake of salt water.”

B., page 80. Mr. William Barnard Boddy on “Diet and Cholera”: “The nourishment we derive from the flesh of some animals is not so compatible with the well-being of our constitutional wants as others, particularly the swine, which was altogether prohibited by the Jewish lawgiver, independent of its spiritual enactments, because it produced ‘leprosy.’ Now pork is largely consumed in England, especially by the poorer classes, and in ninety-nine cases out of every hundred is almost invariably succeeded by diarrhœa; and we need not be surprised at this when we look at the filthy habits of this animal; its impure feeding and liability to the diseases of measles and scarlet-fever. But when we know that they are often in this state killed and sold as an article of food, the liability to disease of course is much greater. But this is not all, as relates to this class of society, for almost – I might say positively so – every article upon which they subsist is impoverished by vile adulterations, and worse, putrefactions; their limited means enabling them to procure only the half-decomposed refuse of the vegetable market, and the half-tainted meat from the butchers’ shambles.

“The more wealthy command all the luxuries of life in abundance, and, agreeable to their inclinations and appetites, feast accordingly. Over-indulgence however, often repeated, at last exhausts the healthy tone of the stomach, and blunts the keen edge of desire; and in order to produce a false appetite, condiments of various kinds and degrees are substituted; so that, in fact, the food becomes nearly as vitiated by these additions as that of the poor man’s by subtractions – the one of necessity, the other of choice. Extremes meet, and here ‘the rich and poor meet together;’ for under both circumstances the animal economy must severely suffer, and the ‘blood, which is the life,’ becomes weak and serous; and though for a time, from the great reluctance health has to depart, the growing evils of an impure and unwholesome diet may not be perceived or apprehended, yet insensibly, from the perpetual inroads made upon the constitution, and the delicate seat of life, the efforts to resist disease become weaker and weaker, till at last the whole mass is left without any internal active principle of sound health available to resist or overcome its effects.”

THE END1

The saliva, besides containing water, ptyaline, fatty matter, and albumen, holds in solution chloride of sodium and potassium, besides the sulphate of soda and the phosphates of lime and magnesia. The amount secreted during twenty-four hours has been estimated at from two to three pints.

2

Their food, according to geologists, consisted solely of shell-fish.

3

This sea is called by several names, viz., “The Dead Sea,” “The Sea of the Plain,” or “of the Arabah,” and “The East Sea.” In the 2nd Book of Esdras v. 7, it is called the “Sodomish Sea.” Josephus uses a similar name, ἡ Σοδομύτυς λίμνη – the Sodomite Lake; he also calls it by the same name as Diodorus Siculus, the “Asphaltic Lake” – ἡ Ἀσφαλτίτις λίμνη. It contains 26 per cent. of salt, including large quantities of magnesium compounds; its weight is of course great, a gallon weighing almost 12-1/2 lb.; and its buoyancy is proportionate to the weight, being such that the human body cannot sink in it. At the south side is a mass of crystallised salt, and in it is a very peculiar cavern, extending at least five miles, varying in height from 200 to 400 feet. This sea is 1312 feet below the level of the Mediterranean; the river Jordan, from the Sea of Galilee, flows into it, but no river flows from it.

4

According to C. Velleius Paterculus of Rome, Homer flourished B.C. 968; according to Herodotus, B.C. 884; the Arundelian Marbles fix his era B.C. 907.

5

To show how acute the Greek mind must have been, and how alive the philosophers of that classic country were to everything, whether beautiful or useful, we need only call to mind the quaint observation of Zeno, the founder of the Stoics, who was born about B.C. 300, and who says that “a soul was given to the hog instead of salt, to prevent his body from rotting;” by this we see he was quite cognisant of the preservative properties of salt.

6

Between the Nile and the Red Sea there are quarries of white marble, of porphyry, of basalt, and the beautiful green breccia, known as Verde d’Egitto; in the same locality are found gold, iron, lead, emerald, and copper.

7

A learned author states as follows: “We have seen, too, that the earliest state of Egypt, as seen in the pyramids, and in the tombs of the same age, reveals an orderly society and civilisation, of which the origin is unknown.”

8

No doubt they were proud of their African parentage, and looked upon the hoary monarchy of the Nile with a sentiment of religious awe and unfeigned wonder. Baron Bünsen graphically puts it: “Egypt was to the Greeks a sphinx with an intellectual human countenance.”

9

Probably owing to the existence of salt in Western Thibet and in Lahore, a province of Hindostan, also the Indian Salt Range, which stretches in a sigmoid curve, according to the late researches of Mr. Wynne, from Kalabagh on the Indus to a point north of Tank, both the Chinese and Hindoos may have been equally cognisant of its virtues with the Egyptians, especially when we have it recorded that the Celestials procured it by a process not only original but in a certain degree characteristic of Asiatic combination of ingenuity and clumsiness.

10

Baron Bünsen says that “No nation of the earth has shown so much zeal and ingenuity, so much method and regularity in recording the details of private life, as the Egyptians.” They were also most expert engineers; the canal from the Nile to the Red Sea, which may be called the canal of Rameses II., being protected at the Suez mouth by a system of hydraulic appliances to obviate difficulties arising from the variable levels of the water.

11

“It is a strange fact that the early Egyptians, like the Hindoos, had a religious dread of the sea,”(?); and yet in the reign of Necho, the son of Psammetichus, they actually accomplished the circumnavigation of Africa: the voyage took three years.

12

Dr. Draper’s “History of the Intellectual Development of Europe.”

13

“One momentous consequence of the Shepherd conquest appears to have been that the expelled Shemites carried back with them into Syria the arts and letters of Egypt, which were thence diffused by the maritime Phœnicians over the opposite shores of Greece. Thus Egypt began at this epoch to come in contact at once with the East and the West, with Asia and with Europe.”

14

“Euterpe,” book ii. chap. lxxvii.

15

Lord Bacon mentions somewhere in his works that the ancients discovered that salt water will dissolve salt put into it in less time than fresh water. The same great philosopher also affirms that “salt water passing through earth through ten vessels, one within another, hath not lost its saltness; but drained through twenty, becomes fresh.”

16

The Russians have a custom of presenting bread and salt to the newly-married bride and bridegroom. In archæology we have salt-silver, one penny at the feast of St. Martin, given by the tenants of some manors, as a commutation for the service of carrying their lord’s salt from market to his larder; an old English custom.

17

According to the researches of the late Mr. George Smith, Babylonian literature is of a much more ancient date than the histories of the Bible; which fact would tend to indicate that the intellectual development of that Eastern monarchy may have been coëval with that of the African.

18

Dr. Draper’s “History of the Intellectual Development of Europe.”

19

Leviticus ii. 13.

20

2 Kings ii. 21.

21

Judges ix. 45.

22

2 Chronicles xiii. 5.

23

Numbers xviii. 19.

24

Ezekiel xvi. 4.

25

Job v. 6.

26

St. Mark ix. 50.

27

Ibid.

28

Huxley’s “Physiography.”

29

Sir Robert Christison’s “Treatise on Poisons.”

30

Sea-water contains 2·5 per cent. of the chloride of sodium; some say 4 per cent.; according to others, 5·7.

31

It is well worth remembering that the Thames carries away from its basin above Kingston 548,230 tons of saline matter annually.

32

Hence arose the custom of asking for salt at the Eton Montem.

33

Sir R. S. Murchison, “The Mineral Springs of Gloucestershire and Worcestershire.”

34

Dr. Mantell’s “Wonders of Geology.”

35

There are the noted salt-works near Portobello, Edinburgh, which have been so truthfully presented to us on canvas by Mr. Edward Duncan.

36

In Prussia salt is obtained from the brine-springs of that part of Saxony which is subject to her jurisdiction. It also exists in abundance in Bavaria and Würtemberg; and it is the chief mineral production of the Grand Duchy of Baden.

37

“In one village they only found one earthen pot containing food, which Bruce took possession of, leaving in its place a wedge of salt, which, strange to say, is still used as small money in Gondar and all over Abyssinia.” – Bruce’s “Travels in Abyssinia.”

38

Polymnia, book vii. chap. xxx.

39

The geographical features of this almost unknown country are peculiarly interesting, and are unique when compared with others; the great height of its mountains, its remarkable elevation, the large rivers which take their rise here, and the numerous salt lakes, the altitude of some being from 13,800 to 15,400 feet above the level of the sea, all combine to excite our curiosity, which is increased by the fact that we know next to nothing of the interior or of the habits of the people.

40

“Many springs in Sicily contain muriate of soda; and the ‘fuime salso’ in particular is impregnated with so large a quantity that cattle refuse to drink it. There is a hot spring at St. Nectaire, in Auvergne, which may be mentioned as one of many, containing a large proportion of muriate of soda, together with magnesia and other ingredients.” – Sir Charles Lyell’s “Principles of Geology.”

41

The Jurassic formation presents a remarkable contrast with that of the Triassic, in the profusion of organic remains; for while the latter contains next to none, the former teems with marine fossils, a proof that the strata were unfavourable for the preservation of organic structures. – Dr. Mantell’s “Wonders of Geology.”

42

There is a mountain composed entirely of rock-salt not far from this old Moorish city; it is 500 feet in height and three miles in circumference; it is completely isolated, and gypsum is also present. In other countries there are similar enormous masses, which require to be dug out and pulverised by machinery on account of their hardness.

43

Gypsum, or sulphate of lime, consists of sulphuric acid 46·31, lime 32·90, and water 20·79. The massive gypsum is called Alabaster; the transparent gypsum Selenite; powdered calcined gypsum forms Plaster of Paris. The fibrous gypsum has a silken lustre, and is used for ear-rings, brooches, and other ornaments. Fibrous gypsum of great beauty occurs in Derbyshire; veins and masses of this substance abound in the red marls bordering the valley of the Trent.

44

Geological Journal, vol. iii. p. 257.

45

Pereira’s “Materia Medica,” vol. i. p. 581.

46

Sir Charles Lyell’s “Principles of Geology.”

47

In the great desert of Gobi, which is supposed to have been originally the bed of the sea which communicated through the Caspian with the Baltic, as confirmatory of this theory, salt is found in great quantities mixed with the soil. To go a step further, we may infer that the lake in Western Thibet (called Tsomoriri) may have been in prehistoric times joined with this vanished sea, and if so would account for its being saline.

48

Sir Charles Lyell’s “Principles of Geology.”

49

In rocks of igneous origin, of which there are many and varied sorts in Australia, no fossils are found except in those rare cases where animal or vegetable bodies have become invested in a stream of lava or overwhelmed by a volcanic shower.

50

Pigeons are always attracted by a lump of salt, and there is a kind of bait called a salt-cat which is usually made at salt-works.

51

“Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.”

52

See page 28, chap. iii.

53

During the famine in Armenia in the year 1880 the people were most distressed because they had no means to supply themselves with salt, the want of which they felt even more than the lack of food.

54

It is an interesting fact that the gastric juice varies in different classes of animals, according to the food on which they subsist; thus in birds of prey as kites, hawks, and owls, it only acts on animal matter, and does not dissolve vegetables; in other birds, and in all animals feeding on grass, as oxen, sheep, and hares, it dissolves vegetable matter, as grass, but will not touch flesh of any kind.