полная версия

полная версияThe History of Salt

Though salted provisions solely are not altogether conducive to health, or contributive towards preserving the due equalisation of the constituents of the blood, I cannot see that they entirely originate scurvy, as some assert; I am of an opinion that this disease is caused principally by seamen’s peculiar habits, and the surroundings belonging to a seafaring life, joined, much more frequently than some would like to confess, with the ingestion of animal food just rescued from putrescence by a timely immersion in brine.

Everything, as is well known, can be used and abused, and salt, like other natural productions, owing to human avarice, can be put to a purpose so as to derange and render nugatory the laws of health. We know full well that salt completely arrests the formation of putrescent larvæ in meat, if it is rubbed in when fresh, or if it is well soaked in strong brine; and if the meat is bordering on decomposition, we may prevent it proceeding to a more advanced stage by immersing it in brine; still it is not in a condition fit for human consumption. Such food in my opinion is of a nature calculated to produce disease of a most virulent type; indeed it is quite sufficient to produce the worse form of scurvy, let alone the outbreaks of a milder degree.

I am acquainted with the fact that a diet consisting exclusively of salt pork and salt beef, with very little variation or change, would be, if continued for any length of time, combined with the absence of fresh vegetables, productive of much mischief, and in the end no doubt scurvy would be the result; but for us to assert that every outbreak of this disease is produced by salted provisions, is to run into a very ridiculous error, and we fall into a trap cunningly laid for us by those whose interest it is to keep up this preposterous imposition in the eyes of the not too discerning public. If shipowners took more care in provisioning their ships with wholesome food, instead of allowing them to be stored with bad pork, putrid beef, and rotten biscuits, we should not read the heart-sickening accounts so frequently in the newspapers. It is all very well for them to assert that the disease springs from salt, and the absence of vegetable food; it is to their interest to say so. We can cast their flimsy statements to the winds, however, and give them an emphatic contradiction, for their proceedings in this matter will not bear even a partial investigation.

I have gone more fully into this part of my subject than I intended, for the following reason: the advocates of total abstention from salt invariably bring forward scurvy as a conclusive proof of their argument, and as unanswerable; they have not looked at it, I am afraid, from the above standpoint, and I think if they will take the trouble to go into the matter more thoroughly, they will find that scurvy originates, not from wholesome salted provisions and the want of vegetables, but from impure and putrid food, which too many owners of ships, from pecuniary motives, prefer to supply, not for the passengers – that would of course be unwise policy – but for the men who labour for them on the waters, and who are at the mercy of employers as insatiable and inexorable in obtaining their pounds of flesh as the storm-tossed ocean yawning for its victims.

“Digestion is the process by which those parts of our food which may be employed in the formation and repair of the tissues, or in the production of heat, are made fit to be absorbed and added to the blood.”

I do not think it will be out of place to make a few cursory observations on the process of digestion, for as scurvy is the result of the ingestion of unwholesome food, we cannot do better than consider the process in relation to salt, and its action on animal and vegetable food while it is in the stomach.

When this organ is empty it is completely inactive; there is no secretion of the gastric juice, and the mucus, which is slightly alkaline or neutral, covers the surface; but immediately food is introduced, the mucous membrane, which was pale, at once becomes turgid, owing to the greater influx of blood; because when any organ has work to perform, it requires an increased supply.

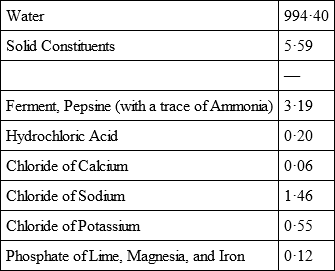

The amount of the gastric juice secreted has been variously estimated to be from ten to twenty pints a day in a healthy adult, and by the following table, we find that salt, or rather the chloride of sodium, is present in a considerable quantity. Looking, then, at the immense secretion of the gastric juice, salt is really in continual requisition, making it self-evident that if the supply is not kept up in the same ratio, digestion is retarded, the food passes out of the stomach in an undigested state into the duodenum, and the stomach is consequently overstrained because of the loss of one of its most important constituents; the supply of salt not being equal to the demand.

Composition of Gastric Juice.

In a sheep’s gastric juice there is to 971·17 of water, 4·36 of chloride of sodium, showing at once how highly necessary it is for cattle to be supplied with it; a sheep will consume on the average half an ounce of salt daily; that it tends to prevent an outbreak of the rot, I have already drawn the attention of the reader.54

There is we see 0.20 of hydrochloric acid to 994.40 of water in the gastric juice, though some are of an opinion that it is lactic acid; the weight of evidence is decidedly in favour of free hydrochloric acid.

Food when it is going through the process of digestion is reduced to a pulp by the solvent properties of the gastric juice, which are due to the presence of the animal matter or pepsine, and the hydrochloric acid; neither of these two constituents can digest separately, they must be together; and they must be in that proportion as we have before us in the preceding table; to act as complete disintegrators and solvents.

The general effect of digestion is the conversion of the food into what is called chyme; and though the various materials of a meal are entirely dissimilar in their composition, whether they are azotised or nitrogenous, and non-azotised or non-nitrogenous; when they are once reduced to this condition, viz., chyme, they hardly admit of recognition.

The reader may naturally suppose “that the readiness with which the gastric fluid acts on the several articles of food, is in some measure determined by the state of division, and the tenderness and moisture of the substance presented to it,” and he may also be aware of the fact, that the readiness with which any substance is acted upon by the gastric juice, does not necessarily imply that it possesses nutritive characteristics, for it stands to reason that a substance may be nutritious, and yet hard to digest; and when this is the case, the gastric follicles supply a greater quantity of fluid, in order to effect the conversion of the food into chyme. Pepsine and the hydrochloric acid, the two indispensable and inseparable solvents, are consequently secreted in greater abundance in order to meet and overcome the difficulty, so that the food may be in a condition fit for assimilation with the various tissues.

Man requires a mixed kind of aliment, therefore he must have animal as well as vegetable food, though there are many instances of people who live wholly on animal or vegetable substances; these of course are anomalies, and therefore their habits are unnatural. Vegetarianism is a foolish freak of the weak-minded and semi-ignorant; the structure of the teeth of man points conclusively to the fact that he is both carnivorous and herbivorous; though these vegetable philosophers would have us believe that he is destined to feed upon cabbages!

Food is divided into two groups, nitrogenous and non-nitrogenous, or animal and vegetable; the only non-nitrogenous organic substances of the animal, or nitrogenous, are furnished by the fat, and in some few cases by those vegetable matters that may happen to be in the organs of digestion of those animals who are eaten whole.

Nutritive or plastic, is given to those principles of food which are converted into fibrine or albumen of blood, and being assimilated by the various tissues through its medium, and those principles comprising the major part of the non-nitrogenous food, in the form of fat, gum, starch, and sugar, and other substances of a similar nature, are supposed to be utilised in the production of heat, and are termed calorifaciant, or sometimes respiratory food. The principal ordinary articles of vegetable food contain identical substances, in composition, with the fibrine, caseine, and albumen, which constitute the chief nutritive materials of animal food; for instance, the gluten which is present in corn is identical in composition with fibrine, and is therefore called vegetable fibrine; legumen, which exists in beans, peas, and other seeds of the leguminosæ, is similar to the caseine of milk; and albumen is most abundant in the seeds and juices of nearly all vegetables.

On carefully analysing the preceding remarks on food and some of its uses after it has been digested, and the composition and properties of the gastric juice, it is obvious that salt is not only a simple adjunct to food, and therefore not of much importance, but is an article of diet in every sense of the word, and as necessary, if not more so, than many aliments which are regarded as essential.

In its relations to animal or nitrogenous, and vegetable or non-nitrogenous, food, salt is in every respect important.

The hydrochloric acid of the gastric juice, which is so bountifully secreted by the glands of the stomach, of course drains the whole system of its salt, and especially does it draw the chloride of sodium from the blood, which contains 3·6 in 1000, being held in solution by the liquor-sanguinis.

Animal or nitrogenous food contains only a minimum of salt, which chiefly exists in the muscular tissue, its principal constituents being albumen and fibrine; if, therefore, it is eaten as a rule without salt, digestion is by no means facilitated, because meat being comparatively tough, the glands have to secrete an increased quantity in order to break down or disintegrate it, and there is, as I have observed, a greater drain on the system.

Vegetable or non-nitrogenous food contains potash; only those vegetables growing near the sea contain soda. The same reasons which apply to animal food hold good as regards vegetable, with this difference: the gluten, the legumen, and their other ingredients are acted upon by the gastric juice more rapidly, and that being the case, a less amount is required, and as a natural consequence less salt, or rather chloride of sodium, is abstracted from the blood; because the more the stomach is called upon to exert itself, a greater flow of blood to that viscus is the result, which takes place only when the food to be acted upon is of a harder or tougher material than ordinary, when the organ is filled to repletion, or when salt is omitted as a rule.

Another fact should be borne in mind: cellulose is a substance invariably present in the vegetable kingdom, and is found both in low and high plants; it is present in the fungus as well as in the palm, in the lichen as well as in the oak; it is not subject to climatic influences nor to atmospheric changes, so that its quantity in all plants is always the same. This cellulose is almost identical in its composition with starch, which is a substance entirely non-nutritious. When in the system starch undergoes a transformation, by some process not as yet clearly defined, into sugar; whether in the stomach or by some action of the liver, physiologists are uncertain, but it is an unexplained physiological fact, nevertheless. Sugar, we know, is a very active agent in the production of fat; therefore it is not desirable for us to have an overplus, but rather to keep it under. Salt is not a fat-producer; it has an opposite effect; therefore it should be used plentifully with vegetable food in order to neutralise the effect of the starch or cellulose.

We thus see that this substance cellulose is identical with starch; that starch is turned into sugar, and that sugar promotes the growth of fat. I have already mentioned that stout and fat persons require more salt than those who are spare; therefore we may see at a glance how necessary it is for us to use salt liberally with oleaginous food, and indeed with all which tends to increase the adipose tissue.

Those who have a predisposition to obesity, and who wish to reduce their bulk, cannot take better means to obtain the object of their desire than to use salt at all their meals, and to take care that their food is of the plainest; then with a proper amount of exercise and attention to the secretions, they will find that instead of carrying a distended, cumbersome abdomen about with them, attended with miserable inconveniences, they will have the felicity of experiencing not only a diminution of size, but a more easy and expeditious locomotion; and they will be enabled to

“Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuffWhich weighs upon the heart.”If they wish to effect their purpose more speedily, Glauber’s salt waters, which contain salt, can be taken with advantage, for they decrease the fat and assist digestion and assimilation. “In the same way chloride of sodium may be shown to be a more important ingredient than is sometimes supposed. It stimulates gently the mucous membrane of the alimentary canal, and also the muscular fibres of the intestines; when absorbed it promotes tissue-change, and apparently aids the cell formation. Its digestive action is well known.”55

According to Dr. Rawitz, who has examined microscopically the products of artificial digestion and the excreta after the same food, cells, both animal and vegetable, pass through the alimentary canal completely unchanged, such as cartilage and fibro-cartilage, except that of fish, which fact is indicative that it is more digestible than any other aliment; elastic fibre is also unchanged, and fat-cells are frequently found altogether unaltered; also after eating fat pork, the pabulum of the lower classes, crystals of cholesterine are invariably to be obtained from the excreta.

Quantities of cell-membrane of vegetables are found in the alvine evacuations, likewise starch-cells, with only part of their contents removed, and the green colouring principle, chlorophylle, is never changed.

From the foregoing we see at once the kind of food necessary, as regards its sustentative and nutritious properties, and that which merely serves as an unimportant adjunct.

Dr. Rawitz does not inform us whether a greater or lesser amount of salt was used in his experiments; being regarded as an unimportant item, he probably may have been indifferent as to whether it was used or not, and took no note of the quantity. As nothing was found in the excreta belonging to fish, we may regard it as favouring the view, that being impregnated with salt, and living in salt water, the facility with which it is digested is mainly owing to the presence of salt. Fresh-water fish, as is well known, are not digested so easily and thoroughly as those which live in the sea. Again, Dr. Rawitz does not tell us whether the fish used in his experiments were salt or fresh; I conclude that they were salt, because the consumption of fresh-water fish is considerably below the number of that caught at sea.

Those who believe that man is an organism of vegetable proclivities, and would have him live upon vegetables exclusively, who point with a triumphant smile to scurvy as resulting solely from long-continued abstention from vegetable food, combined with the ingestion of salted meat, should remember that any kind of food indulged in to the exclusion of others injures the health, reduces the physical strength, and deteriorates the blood. They are right as far as their argument goes, but they lose sight of some very remarkable facts when they describe scurvy as originating from salt.

Vegetables which are generally used as aliment are young and fresh; on board ship, and especially in long voyages, they are in nine cases out of ten old and musty, and those belonging to the compositæ, such as cabbages, rapidly degenerate into decomposition, generating a very poisonous gas, viz. sulphuretted hydrogen; while those belonging to the leguminosæ, as peas and beans, lose their great nutritious principle, legumen, which is identical with the caseine of milk, and which renders them such invaluable articles of diet. Besides, if vegetables are kept for any length of time, even if excluded from the air, they are liable to rapid decomposition immediately they are exposed to its influences. I therefore think, as I have asserted already, that salted meat is not wholly responsible for scurvy, and that it much more frequently arises from its being salted in the early stages of putrescence.

These vegetable reformers and abstainers from salt are, I am afraid, ignorant of these facts.

If mankind were to act in accordance with the wishes of visionaries, and those who are prone to scientific credulity, and who look upon themselves as philanthropic philosophers, we should speedily be reduced to the unenviable condition of the Frenchman’s horse; for to some, animal food is pernicious, salt is in some respects poisonous, water is to be discarded as worse than useless, stimulants in the hour of sickness are to be avoided, and are never to be touched; vegetables are mere woody fibre or starch-cells. They are considerate, however; they have left us fish! This staple of food is not yet ostracised.

Happy is the man who lives according to the dictates of nature, temperately and wholesomely, and who does not run like a thoughtless being into extremes, originating from hare-brained fanatics, and from unpractical utilitarians.

Salt is a preventive of those disfiguring eruptions which frequently affect the young about the face and neck, and which in the majority of cases arise from a defective state of the blood. One need only take a stroll through a crowded thoroughfare to find that this is the fact. These young people, instead of possessing complexions which are indicative of health and purity of blood, carry in their countenances unmistakable marks which cannot escape the eye of an observant and discriminating passer-by. If we were to make inquiries, we should find that they are, with few exceptions, absolute strangers to salt, and that probably they have been brought up from their infancy by their parents never to touch it.

This neglect shows the grossest ignorance on the part of these people, and calls for the most stringent censure; it is almost incredible, to find so many unaccustomed to the use of salt, and who never impress upon their children the need of it, and that the continuance of their health is partly dependent upon a daily use of a substance which is a highly important constituent of the blood.

I have drawn my reader’s attention to the facts that the blood of scrofulous persons is deficient in salt, that the amount is variable, and that the deficiency is at once discernible in the objectionable condition of the skin of the face and neck; but here we have people enjoying a fair share of health, who, owing to ignorance or indifference, are reducing themselves to a state bordering on disease, and who would otherwise be total strangers to those ailments which only attack the impure, the luxurious and intemperate.

We have seen that salt is necessary in the animal economy, otherwise it would not exist as a constituent of the blood. It is equally necessary for the preservation of health; for in the blood of those people who are suffering from disease, we detect a visible decrease. In some cases of fever the diminution is remarkable; if the febrile symptoms increase in severity, we find that there is a corresponding loss of the chloride of sodium. This simple fact alone shows that it is the imperative duty of those who have at heart the well-being of their fellow-creatures, to impress upon them in emphatic language, that if they wish their blood to be in a pure healthy condition, and to be able to ward off the insidious attacks of disease, they must make it a frequent article of diet.

We are all cognisant that disease will be to the end of time one of the scourges of humanity; and at the present day certain maladies are spreading amongst us with the greatest rapidity, all our efforts to eradicate them having been hitherto altogether futile, and the results far from promising. All our medicines, our improved modes of treatment, and our hygienic schemes, ingenious as they undoubtedly are, reflecting the highest honour on their philanthropic originators, have been, and still are to a considerable extent, abortive, and we are still combating with, and succumbing to, this inveterate enemy of mankind.

We do not diet ourselves as we should; in this respect we are far behind the veriest savage, cannibal though he be: he in his natural state obeys the laws and dictates of nature, which we in our civilised state decidedly do not, notwithstanding the assertions of the dreamy philosophers of the day. He sleeps when nature prompts him, regardless of the sun’s heat or midnight dews; he eats when he is hungry, and drinks when he is thirsty; he goes through a certain amount of physical fatigue; his clothing is of the simplest kind; his food on the average is the purest; his drink is that natural fluid which we, owing to our high state of civilisation, so pertinaciously and foolishly discard; he roams at pleasure either on the desert or in the forest; and his impulses, though savage, are never at variance with nature; he is, in fact, as real a child of nature as an average civilised European is the slave of a falsified nature.

Those who have travelled in the islands of the Pacific Ocean have informed us that their inhabitants, with but few exceptions, possess the secret of extracting salt from certain substances, which indicates that even they are fully alive to its virtues, and proves to us, who boast of our superiority, that we are deficient of natural acumen, or that it is marred and stultified by those silly customs arising from that curse of civilisation, fashion, which makes slaves of us all, at least of the weak-minded and frivolous.

At the tables of the wealthy it is perfectly absurd to see the small amount of salt which is placed in the smallest receptacles, as if it were the most expensive article; and it is equally ridiculous to see the host and his guests, in the most finical grotesque manner, help themselves to the almost infinitesimal quantities of salt, as if it were a mark of good breeding and delicacy. This is how we pervert nature; our civilisation is a great good, undoubtedly, but at the same time it is frequently at variance with what is good for us. If the blind votaries of fashion think that it is polite to use the gifts of nature in such a way as to render them comparatively useless, let those who wish to enjoy the blessings of health, pure blood, and a wholesome, transparent skin, refrain from those stupid customs of “good society,” which are truly indicative of mental weakness and most profound ignorance.

I have known people who accustom themselves to the use of salt baths, and who talk very glibly of the luxury of sea-bathing, who yet are in complete ignorance of the virtues of salt as a condiment and as a preserver of health, and who try to prove that salt so used is obnoxious, and consequently to be avoided. These salt baths are popular, not because they are beneficial, but by reason of their comparative novelty; and accordingly, many who would not think of using salt with their food, plunge headlong into the sea or into a salt-water bath, with all the vigour possible.

Salt baths are presumed by some to be of great value in gout; Droitwitch in particular is famous for them; many who were considered as incurable have alleged that after having used them, they have returned home cured.

The topical application of salt water to weak joints, etc., has only just come to the front; and by many it is regarded as quite a new remedy; and I have heard some very disparaging observations on the medical profession regarding its negligence to, or indifference of, the restorative properties of salt water, alleging that it has been reluctantly forced to advise it, in deference to the popular opinion in its favour. It is indeed a fact that until a few years ago, medical men as a rule were utterly unacquainted with salt water as a remedial agent; and the idea no doubt would have been denounced with as much asperity and contumely as the hydropathic treatment is at the present day, and with as much reason. It is a mistake, however, to assume that it is of recent origin, for my father, Mr. Wm. Barnard Boddy, has been in the habit of advising it for over the last sixty years, and with almost uniform success.