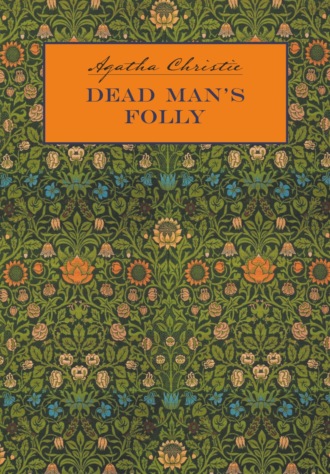

Полная версия

Причуда мертвеца / Dead Man's Folly. Книга для чтения на английском языке

‘Yes, indeed. What’s the good of a woman like that? What contribution has she ever made to society? Has she ever had an idea in her head that wasn’t of clothes or furs or jewels? As I say, what good is she?’

‘You and I,’ said Poirot blandly, ‘are certainly much more intelligent than Lady Stubbs. But’—he shook his head sadly—‘it is true, I fear, that we are not nearly so ornamental.’

‘Ornamental…’ Alec was beginning with a fierce snort, but he was interrupted by the re-entry of Mrs Oliver and Captain Warburton through the window.

CHAPTER 4

‘You must come and see the clues and things for the Murder Hunt, M. Poirot,’ said Mrs Oliver breathlessly.

Poirot rose and followed them obediently.

The three of them went across the hall and into a small room furnished plainly as a business office.

‘Lethal weapons to your left,’ observed Captain Warburton, waving his hand towards a small baize-covered card table. On it were laid out a small pistol, a piece of lead piping with a rusty sinister stain on it, a blue bottle labelled Poison, a length of clothes line and a hypodermic syringe.

‘Those are the Weapons,’ explained Mrs Oliver, ‘and these are the Suspects.’

She handed him a printed card which he read with interest.

Suspects

Estelle Glynne – a beautiful and mysterious young woman, the guest of

Colonel Blunt – the local Squire, whose daughter Joan – is married to

Peter Gaye – a young Atom Scientist.

Miss Willing – a housekeeper.

Quiett – a butler.

Maya Stavisky – a girl hiker.

Esteban Loyola – an uninvited guest.

Poirot blinked and looked towards Mrs Oliver in mute incomprehension.

‘A magnificent Cast of Characters,’ he said politely. ‘But permit me to ask, Madame, what does the Competitor do?’

‘Turn the card over,’ said Captain Warburton.

Poirot did so.

On the other side was printed:

Name and address .........................

Solution:

Name of Murderer: ........................

Weapon: .............................................

Motive: ...............................................

Time and Place: ..............................

Reasons for arriving at your conclusions:

...............................................................

‘Everyone who enters gets one of these,’ explained Captain Warburton rapidly. ‘Also a notebook and pencil for copying clues. There will be six clues. You go on from one to the other like a Treasure Hunt, and the weapons are concealed in suspicious places. Here’s the first clue. A snapshot. Everyone starts with one of these.’

Poirot took the small print from him and studied it with a frown. Then he turned it upside down. He still looked puzzled. Warburton laughed.

‘Ingenious bit of trick photography, isn’t it?’ he said complacently. ‘Quite simple once you know what it is.’

Poirot, who did not know what it was, felt a mounting annoyance.

‘Some kind of barred window?’ he suggested.

‘Looks a bit like it, I admit. No, it’s a section of a tennis net.’

‘Ah.’ Poirot looked again at the snapshot. ‘Yes, it is as you say—quite obvious when you have been told what it is!’

‘So much depends on how you look at a thing,’ laughed Warburton.

‘That is a very profound truth.’

‘The second clue will be found in a box under the centre of the tennis net. In the box are this empty poison bottle—here, and a loose cork.’

‘Only, you see,’ said Mrs Oliver rapidly, ‘it’s a screw-topped bottle[52], so the cork is really the clue.’

‘I know, Madame, that you are always full of ingenuity,

but I do not quite see—’

Mrs Oliver interrupted him.

‘Oh, but of course,’ she said, ‘there’s a story. Like in a magazine serial—a synopsis.’ She turned to Captain Warburton. ‘Have you got the leaflets?’

‘They’ve not come from the printers yet.’

‘But they promised!’

‘I know. I know. Everyone always promises. They’ll be ready this evening at six. I’m going in to fetch them in the car.’

‘Oh, good.’

Mrs Oliver gave a deep sigh and turned to Poirot.

‘Well, I’ll have to tell it you, then. Only I’m not very good at telling things. I mean if I write things, I get them perfectly clear, but if I talk, it always sounds the most frightful muddle; and that’s why I never discuss my plots with anyone. I’ve learnt not to, because if I do, they just look at me blankly and say “—er—yes, but—I don’t see what happened—and surely that can’t possibly make a book.” So damping. And not true, because when I write it, it does!’

Mrs Oliver paused for breath, and then went on:

‘Well, it’s like this. There’s Peter Gaye who’s a young Atom Scientist and he’s suspected of being in the pay of the Communists, and he’s married to this girl, Joan Blunt, and his first wife’s dead, but she isn’t, and she turns up because she’s a secret agent, or perhaps not, I mean she may really be a hiker—and the wife’s having an affair, and this man Loyola turns up either to meet Maya, or to spy upon her, and there’s a blackmailing letter which might be from the housekeeper, or again it might be the butler, and the revolver’s missing, and as you don’t know who the blackmailing letter’s to, and the hypodermic syringe[53] fell out at dinner, and after that it disappeared…’

Mrs Oliver came to a full stop, estimating correctly Poirot’s reaction.

‘I know,’ she said sympathetically. ‘It sounds just a muddle, but it isn’t really—not in my head—and when you see the synopsis leaflet, you’ll find it’s quite clear.

‘And, anyway,’ she ended, ‘the story doesn’t really matter, does it? I mean, not to you. All you’ve got to do is to present the prizes—very nice prizes, the first’s a silver cigarette case shaped like a revolver—and say how remarkably clever the solver has been.’

Poirot thought to himself that the solver would indeed have been clever. In fact, he doubted very much that there would be a solver. The whole plot and action of the Murder Hunt seemed to him to be wrapped in impenetrable fog[54].

‘Well,’ said Captain Warburton cheerfully, glancing at his wrist-watch, ‘I’d better be off to the printers and collect.’

Mrs Oliver groaned.

‘If they’re not done—’

‘Oh, they’re done all right. I telephoned. So long.’

He left the room.

Mrs Oliver immediately clutched Poirot by the arm and demanded in a hoarse whisper:

‘Well?’

‘Well—what?’

‘Have you found out anything? Or spotted anybody?’

Poirot replied with mild reproof in his tones:

‘Everybody and everything seems to me completely normal.’

‘Normal?’

‘Well, perhaps that is not quite the right word. Lady Stubbs, as you say, is definitely subnormal, and Mr Legge would appear to be rather abnormal.’

‘Oh, he’s all right,’ said Mrs Oliver impatiently. ‘He’s had a nervous breakdown.’

Poirot did not question the somewhat doubtful wording of this sentence but accepted it at its face value.

‘Everybody appears to be in the expected state of nervous agitation, high excitement, general fatigue, and strong irritation, which are characteristic of preparations for this form of entertainment. If you could only indicate—’

‘Sh!’ Mrs Oliver grasped his arm again. ‘Someone’s coming.’

It was just like a bad melodrama, Poirot felt, his own irritation mounting.

The pleasant mild face of Miss Brewis appeared round the door.

‘Oh, there you are, M. Poirot. I’ve been looking for you to show you your room.’

She led him up the staircase and along a passage to a big airy room looking out over the river.

‘There is a bathroom just opposite. Sir George talks of adding more bathrooms, but to do so would sadly impair the proportions of the rooms. I hope you’ll find everything quite comfortable.’

‘Yes, indeed.’ Poirot swept an appreciative eye over the small bookstand, the reading-lamp and the box labelled ‘Biscuits’ by the bedside. ‘You seem, in this house, to have everything organized to perfection. Am I to congratulate you, or my charming hostess?’

‘Lady Stubbs’ time is fully taken up in being charming,’ said Miss Brewis, a slightly acid note in her voice.

‘A very decorative young woman,’ mused Poirot.

‘As you say.’

‘But in other respects is she not, perhaps…’ He broke off. ‘Pardon. I am indiscreet. I comment on something I ought not, perhaps, to mention.’

Miss Brewis gave him a steady look. She said dryly:

‘Lady Stubbs knows perfectly well exactly what she is doing. Besides being, as you said, a very decorative young woman, she is also a very shrewd one.’

She had turned away and left the room before Poirot’s eyebrows had fully risen in surprise. So that was what the efficient Miss Brewis thought, was it? Or had she merely said so for some reason of her own? And why had she made such a statement to him—to a newcomer? Because he was a newcomer, perhaps? And also because he was a foreigner. As Hercule Poirot had discovered by experience, there were many English people who considered that what one said to foreigners didn’t count!

He frowned perplexedly, staring absentmindedly at the door out of which Miss Brewis had gone. Then he strolled over to the window and stood looking out. As he did so, he saw Lady Stubbs come out of the house with Mrs Folliat and they stood for a moment or two talking by the big magnolia tree. Then Mrs Folliat nodded a goodbye, picked up her gardening basket and gloves and trotted off down the drive. Lady Stubbs stood watching her for a moment, then absentmindedly pulled off a magnolia flower, smelt it and began slowly to walk down the path that led through the trees to the river. She looked just once over her shoulder before she disappeared from sight. From behind the magnolia tree Michael Weyman came quietly into view, paused a moment irresolutely and then followed the tall slim figure down into the trees.

A good-looking and dynamic young man, Poirot thought. With a more attractive personality, no doubt, than that of Sir George Stubbs…

But if so, what of it[55]? Such patterns formed themselves eternally through life. Rich middle-aged unattractive husband, young and beautiful wife with or without sufficient mental development, attractive and susceptible young man. What was there in that to make Mrs Oliver utter a peremptory summons through the telephone? Mrs Oliver, no doubt, had a vivid imagination, but…

‘But after all,’ murmured Hercule Poirot to himself, ‘I am not a consultant in adultery—or in incipient adultery.’

Could there really be anything in this extraordinary notion of Mrs Oliver’s that something was wrong? Mrs Oliver was a singularly muddle-headed woman, and how she managed somehow or other to turn out coherent detective stories was beyond him, and yet, for all her muddle-headedness she often surprised him by her sudden perception of truth.

‘The time is short—short,’ he murmured to himself. ‘Is there something wrong here, as Mrs Oliver believes? I am inclined to think there is. But what? Who is there who could enlighten me? I need to know more, much more, about the people in this house. Who is there who could inform me?’

After a moment’s reflection he seized his hat (Poirot never risked going out in the evening air with uncovered head), and hurried out of his room and down the stairs. He heard afar the dictatorial baying of Mrs Masterton’s deep voice. Nearer at hand, Sir George’s voice rose with an amorous intonation.

‘Damned becoming that yashmak[56] thing. Wish I had you in my harem[57], Sally. I shall come and have my fortune told a good deal tomorrow. What’ll you tell me, eh?’

There was a slight scuffle and Sally Legge’s voice said breathlessly:

‘George, you mustn’t.’

Poirot raised his eyebrows, and slipped out of a conveniently adjacent side door. He set off at top speed down a back drive which his sense of locality enabled him to predict would at some point join the front drive.

His manoeuvre was successful and enabled him—panting very slightly—to come up beside Mrs Folliat and relieve her in a gallant manner of her gardening basket.

‘You permit, Madame?’

‘Oh, thank you, M. Poirot, that’s very kind of you. But it’s not heavy.’

‘Allow me to carry it for you to your home. You live near here?’

‘I actually live in the lodge by the front gate. Sir George very kindly rents it to me.’

The lodge by the front gate of her former home… How did she really feel about that, Poirot wondered. Her composure was so absolute that he had no clue to her feelings. He changed the subject by observing:

‘Lady Stubbs is much younger than her husband, is she not?’

‘Twenty-three years younger.’

‘Physically she is very attractive.’

Mrs Folliat said quietly:

‘Hattie is a dear good child.’

It was not an answer he had expected. Mrs Folliat went on:

‘I know her very well, you see. For a short time she was under my care[58].’

‘I did not know that.’

‘How should you? It is in a way a sad story. Her people had estates, sugar estates[59], in the West Indies. As a result of an earthquake, the house there was burned down and her parents and brothers and sisters all lost their lives. Hattie herself was at a convent in Paris and was thus suddenly left without any near relatives. It was considered advisable by the executors that Hattie should be chaperoned and introduced into society after she had spent a certain time abroad. I accepted the charge of her.’ Mrs Folliat added with a dry smile: ‘I can smarten myself up on occasions and, naturally, I had the necessary connections—in fact, the late Governor had been a close friend of ours.’

‘Naturally, Madame, I understand all that.’

‘It suited me very well—I was going through a difficult time. My husband had died just before the outbreak of war. My elder son who was in the navy went down with his ship, my younger son, who had been out in Kenya, came back, joined the commandos and was killed in Italy. That meant three lots of death duties and this house had to be put up for sale. I myself was very badly off[60] and I was glad of the distraction of having someone young to look after and travel about with. I became very fond of Hattie, all the more so, perhaps, because I soon realized that she was—shall we say—not fully capable of fending for herself[61]? Understand me, M. Poirot, Hattie is not mentally deficient, but she is what country folk describe as “simple.” She is easily imposed upon, over docile, completely open to suggestion. I think myself that it was a blessing that there was practically no money. If she had been an heiress her position might have been one of much greater difficulty. She was attractive to men and being of an affectionate nature was easily attracted and influenced—she had definitely to be looked after. When, after the final winding up of her parents’ estate, it was discovered that the plantation was destroyed and there were more debts than assets, I could only be thankful that a man such as Sir George Stubbs had fallen in love with her and wanted to marry her.’

‘Possibly—yes—it was a solution.’

‘Sir George,’ said Mrs Folliat, ‘though he is a self-made man and—let us face it—a complete vulgarian, is kindly and fundamentally decent, besides being extremely wealthy. I don’t think he would ever ask for mental companionship from a wife, which is just as well. Hattie is everything he wants. She displays clothes and jewels to perfection, is affectionate and willing, and is completely happy with him. I confess that I am very thankful that that is so, for I admit that I deliberately influenced her to accept him. If it had turned out badly’—her voice faltered a little—‘it would have been my fault for urging her to marry a man so many years older than herself. You see, as I told you, Hattie is completely suggestible. Anyone she is with at the time can dominate her.’

‘It seems to me,’ said Poirot approvingly, ‘that you made there a most prudent arrangement for her. I am not, like the English, romantic. To arrange a good marriage, one must take more than romance into consideration.’

He added:

‘And as for this place here, Nasse House, it is a most beautiful spot. Quite, as the saying goes, out of this world.’

‘Since Nasse had to be sold,’ said Mrs Folliat, with a faint tremor in her voice, ‘I am glad that Sir George bought it. It was requisitioned during the war by the Army and afterwards it might have been bought and made into a guest house or a school, the rooms cut up and partitioned, distorted out of their natural beauty. Our neighbours, the Fletchers, at Hoodown, had to sell their place and it is now a Youth Hostel. One is glad that young people should enjoy themselves—and fortunately Hoodown is late-Victorian[62], and of no great architectural merit, so that the alterations do not matter. I’m afraid some of the young people trespass on our grounds. It makes Sir George very angry. It’s true that they have occasionally damaged the rare shrubs by hacking them about—they come through here trying to get a short cut to the ferry across the river.’

They were standing now by the front gate. The lodge, a small white one-storied building, lay a little back from the drive with a small railed garden round it.

Mrs Folliat took back her basket from Poirot with a word of thanks.

‘I was always very fond of the lodge,’ she said, looking at it affectionately. ‘Merdle, our head gardener for thirty years, used to live there. I much prefer it to the top cottage, though that has been enlarged and modernized by Sir George. It had to be; we’ve got quite a young man now as head gardener, with a young wife—and these young women must have electric irons and modern cookers and television, and all that. One must go with the times…’ She sighed. ‘There is hardly a person left now on the estate from the old days—all new faces.’

‘I am glad, Madame,’ said Poirot, ‘that you at least have found a haven.’

‘You know those lines of Spenser’s[63]? “Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas, ease after war, death after life, doth greatly please…”[64]’

She paused and said without any change of tone: ‘It’s a very wicked world, M. Poirot. And there are very wicked people in the world. You probably know that as well as I do. I don’t say so before the younger people, it might discourage them, but it’s true… Yes, it’s a very wicked world…’

She gave him a little nod, then turned and went into the lodge. Poirot stood still, staring at the shut door.

CHAPTER 5

In a mood of exploration Poirot went through the front gates and down the steeply twisting road that presently emerged on a small quay. A large bell with a chain had a notice upon it: ‘Ring for the Ferry.’ There were various boats moored by the side of the quay. A very old man with rheumy eyes, who had been leaning against a bollard, came shuffling towards Poirot.

‘Du ee[65] want the ferry, sir?’

‘I thank you, no. I have just come down from Nasse House for a little walk.’

‘Ah, ’tis[66] up at Nasse yu[67] are? Worked there as a boy, I did, and my son, he were head gardener there. But I did use to look after the boats. Old Squire Folliat, he was fair mazed about boats. Sail in all weathers, he would. The Major, now, his son, he didn’t care for sailing. Horses, that’s all he cared about. And a pretty packet went on ’em. That and the bottle—had a hard time with him, his wife did. Yu’ve seen her, maybe—lives at the Lodge now, she du[68].’

‘Yes, I have just left her there now.’

‘Her be a Folliat, tu[69], second cousin from over Tiverton way. A great one for the garden, she is, all them there flowering shrubs she had put in. Even when it was took over during the war, and the two young gentlemen was gone to the war, she still looked after they shrubs and kept ’em from being over-run.’

‘It was hard on her, both her sons being killed.’

‘Ah, she’ve had a hard life, she have, what with this and that. Trouble with her husband, and trouble with the young gentlemen, tu. Not Mr Henry. He was as nice a young gentleman as yu could wish, took after his grandfather, fond of sailing and went into the Navy as a matter of course, but Mr James, he caused her a lot of trouble. Debts and women it were, and then, tu, he were real wild in his temper. Born one of they as can’t go straight[70]. But the war suited him, as yu might say—give him his chance. Ah! There’s many who can’t go straight in peace who dies bravely in war.’

‘So now,’ said Poirot, ‘there are no more Folliats at Nasse.’

The old man’s flow of talk died abruptly.

‘Just as yu say, sir.’

Poirot looked curiously at the old man.

‘Instead you have Sir George Stubbs. What is thought locally of him?’

‘Us understands,’ said the old man, ‘that he be powerful rich.’

His tone sounded dry and almost amused.

‘And his wife?’

‘Ah, she’s a fine lady from London, she is. No use for gardens, not her. They du say, tu, as her du be wanting up here.’

He tapped his temple significantly[71].

‘Not as her isn’t always very nice spoken and friendly. Just over a year they’ve been here. Bought the place and had it all done up like new. I remember as though ’twere[72] yesterday them arriving. Arrived in the evening, they did, day after the worst gale as I ever remember. Trees down right and left—one down across the drive and us had to get it sawn away in a hurry to get the drive clear for the car. And the big oak up along, that come down and brought a lot of others down with it, made a rare mess, it did.’

‘Ah, yes, where the Folly stands now?’

The old man turned aside and spat disgustedly.

‘Folly ’tis called and Folly ’tis—new-fangled nonsense. Never was no Folly in the old Folliats’ time. Her ladyship’s idea that Folly was[73]. Put up not three weeks after they first come, and I’ve no doubt she talked Sir George into it. Rare silly it looks stuck up there among the trees, like a heathen temple. A nice summer-house now, made rustic like with stained glass. I’d have nothing against that.’

Poirot smiled faintly.

‘The London ladies,’ he said, ‘they must have their fancies. It is sad that the day of the Folliats is over.’

‘Don’t ee never believe that, sir.’ The old man gave a wheezy chuckle. ‘Always be Folliats at Nasse.’

‘But the house belongs to Sir George Stubbs.’

‘That’s as may be—but there’s still a Folliat here. Ah! Rare and cunning the Folliats are!’

‘What do you mean?’

The old man gave him a sly sideways glance.

‘Mrs Folliat be living up tu[74] Lodge, bain’t[75] she?’ he demanded.

‘Yes,’ said Poirot slowly. ‘Mrs Folliat is living at the Lodge and the world is very wicked, and all the people in it are very wicked.’

The old man stared at him.

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Yu’ve got something there, maybe.’

He shuffled away again.

‘But what have I got?’ Poirot asked himself with irritation as he slowly walked up the hill back to the house.

II

Hercule Poirot made a meticulous toilet, applying a scented pomade to his moustaches and twirling them to a ferocious couple of points. He stood back from the mirror and was satisfied with what he saw.

The sound of a gong resounded through the house, and he descended the stairs.

The butler, having finished a most artistic performance, crescendo, forte, diminuendo, rallentando[76], was just replacing the gong stick on its hook. His dark melancholy face showed pleasure.

Poirot thought to himself: ‘A blackmailing letter from the housekeeper—or it may be the butler…’ This butler looked as though blackmailing letters would be well within his scope. Poirot wondered if Mrs Oliver took her characters from life.

Miss Brewis crossed the hall in an unbecoming flowered chiffon dress and he caught up with her, asking as he did so:

‘You have a housekeeper here?’

‘Oh, no, M. Poirot. I’m afraid one doesn’t run to niceties of that kind nowadays, except in a really large establishment, of course. Oh, no, I’m the housekeeper—more housekeeper than secretary, sometimes, in this house.’

She gave a short acid laugh.

‘So you are the housekeeper?’ Poirot considered her thoughtfully.

He could not see Miss Brewis writing a blackmailing letter. Now, an anonymous letter—that would be a different thing. He had known anonymous letters written by women not unlike Miss Brewis—solid, dependable women, totally unsuspected by those around them.