полная версия

полная версияA Girl's Ride in Iceland

Sauderkrok was to witness a new experiment in our mounting arrangements. On our arrival, as usual we intended riding into the interior, and applied at the only inn in the place for ponies, when to our discomfiture we learnt no such thing as a lady's side-saddle was to be obtained. The innkeeper and our party held a long consultation as to what was to be done, during which the inhabitants of the place gathered round us in full force, apparently much interested in our proceedings.

At last one of the lookers-on disappeared, and presently returned in triumph with a chair-saddle, such as already described, used by the native women. This was assigned to Miss T. No second one, however, was obtainable, and I had to choose between remaining behind or overcoming the difficulties of riding lady fashion on a man's saddle. My determination was quickly taken, and much to the amusement of our party, up I mounted, the whole village stolidly watching the proceeding, whilst the absence of pommel contributed considerably to the difficulty I had in keeping my seat.

Off we started, headed by our guide, and as long as the pony walked I felt very comfortable in my new position, so much so that I ventured to try a trot, when round went the saddle and off I slipped. Vaughan came to my rescue, and after readjusting the saddle, and tightening the girths, I remounted, but only with the same result. How was I to get along at this rate?

I had often read that it was the custom for women in South America, and in Albania, who have to accomplish long distances on horseback, to ride man fashion. Indeed, women rode so in England, until side-saddles were introduced by Anne of Bohemia, wife of Richard II., and many continued to ride across the saddle until even a later date. In Iceland I had seen women ride as men, and felt more convinced than ever that this mode was safer and less fatiguing. Although I had ridden all my life, the roughness of the Icelandic roads and ponies made ladywise on a man's saddle impossible, and the sharpness of the pony's back, riding with no saddle equally so. There was no alternative: I must either turn back, or mount as a man. Necessity gives courage in emergencies. I determined therefore to throw aside conventionality, and do in 'Iceland as the Icelanders do.' Keeping my brother at my side, and bidding the rest ride forward, I made him shorten the stirrups, and hold the saddle, and after sundry attempts succeeded in landing myself man fashion on the animal's back. The position felt very odd at first, and I was also somewhat uncomfortable at my attitude, but on Vaughan's assuring me there was no cause for my uneasiness, and arranging my dress so that it fell in folds on either side, I decided to give the experiment a fair trial, and in a very short time got quite accustomed to the position, and trotted along merrily. Cantering was at first a little more difficult, but I persevered, and in a couple of hours was quite at home in my new position, and could trot, pace, or canter alike, without any fear of an upset. The amusement of our party when I overtook them, and boldly trotted past, was intense; but I felt so comfortable in my altered seat that their derisive and chaffing remarks failed to disturb me. Perhaps my boldness may rather surprise my readers; but after full experience, under most unfavourable circumstances, I venture to put on paper the result of my experiment.

Riding man-fashion is less tiring than on a side-saddle, and I soon found it far more agreeable, especially when traversing rough ground. My success soon inspired Miss T. to summon up courage and follow my lead. She had been nearly shaken to pieces in her chair pannier, besides having only obtained a one-sided view of the country through which she rode; and we both returned from a 25 mile ride without feeling tired, whilst from that day till we left the Island, we adopted no other mode of travelling. I am quite sure had we allowed conventional scruples to interfere, we should never have accomplished in four days the 160 miles' ride to the Geysers, which was our ultimate achievement.

I may here mention our riding costume. We had procured very simply made thick blue serge dresses before leaving home, anticipating rough travelling. The skirts being full and loose, hung well down on either side when riding, like a habit on the off and near sides, and we flattered ourselves that, on the whole, we looked both picturesque and practical. Our very long waterproof boots (reaching above the knee) proved a great comfort when fording rivers, which in an Iceland ride are crossed every few miles, sometimes oftener. For the rest, we wore ordinary riding attire.

The crooked position of a side-saddle – for one must sit crooked to look straight – is very fatiguing to a weak back, and many women to whom the exercise would be of the greatest benefit, cannot stand the strain; so this healthy mode of exercise is debarred them, because Society says they must not ride like men. Society is a hard task-master. Nothing is easier than to stick on a side-saddle, of course, and nothing more difficult than to ride gracefully.

For comfort and safety, I say ride like a man. If you have not courage to do this, in visiting Iceland take your own side-saddle and bridle (for a pony), as, except in Reykjavik, horse furniture is of the most miserable description, and the constant breakages cause many delays, while there are actually no side-saddles, except in the capital, and a chair is an instrument of torture only to be recommended to your worst enemy.

On one occasion, while the rest of the party were settling and arranging about ponies, which always occupied some time, I sat down to sketch on a barrel of dried fish, and was at once surrounded by men, women, and children, who stood still and stared, beckoning to all their passing friends to join them, till quite a crowd collected.

They seemed to think me a most extraordinary being. The bolder ones of the party ventured near and touched me, feeling my clothes, discussed the material, and calmly lifted my dress to examine my high riding-boots, a great curiosity to them, as they nearly all wear the peculiar skin shoes already described. The odour of fish not only from the barrel on which I was seated, but also from my admiring crowd, was somewhat appalling as they stood around, nodding and chatting to one another.

Their interest in my sketch was so great I cannot believe they had ever seen such a thing before, and I much regretted my inability to speak their language, so as to answer the many questions I was asked about it all. I fancied they were satisfied, however, for before going away, they one and all shook hands with me, till my hand quite ached from so many friendly grasps.

The men in Iceland always kiss one another when they meet, as also do the women, but I only once saw a man kiss a woman!

'Snuffing' is a great institution. The snuff is kept in a long box, like a gourd, often a walrus tooth, with a long brass mouth. This they put right up the nostril, turning the head to do so – a very dirty and uncouth habit, but one constantly indulged in by both sexes. They also smoke a great deal. On one occasion Vaughan gave a guide some tobacco. He took it, filled his pipe, and put it back in his pocket, shaking his head as much as to say he could not light his pipe in the wind. This dilemma was overcome by Vaughan offering a fusee. The man took it, looked at it, and grinned. So Vaughan showed him how to use it, and struck a light. His astonishment and amusement were so overwhelming that he got off his pony, and rolled about on the ground with delight. He had evidently never seen such a curiosity before.

We rode to Reykir, 10 or 12 miles from Sauderkrok, where there are hot springs. The road was very bad, and it took us nearly three hours to accomplish the distance, but this may be partly accounted for by our stopping every half-hour to mend some one's broken harness. My only girth, a dilapidated old thing, was mended with string, and when trotting along soon after starting, the saddle and I both rolled off together, the only fall I have ever had in my life, and from a little Icelandic pony too! I was thoroughly disgusted at the accident, and my want of balance. However, I soon had occasion to comfort myself on my easy fall, when our guide and pony turned three complete somersaults down a hill, the man disappearing. But he soon rolled out from beneath the animal, shook himself, and mounted once again. How every bone in his body was not broken I can't imagine, so rough and strewn with lava boulders, was the ground on which he fell.

Shortly after our party had left Sauderkrok, a young Icelander was noticed riding after us, and when my fall occurred, he advanced towards us politely, and offered me the use of his pony and saddle, which I gratefully accepted, and he mounted mine, riding without any girths, and gracefully balancing himself in a most marvellous manner. This new addition to our party proved a very valuable one, as he talked English perfectly, and was most intelligent and communicative. He told us he was on his way to Copenhagen to study languages, preparatory to trying for a professorship at Reykjavik, and we found he had already mastered English, French, Latin, and Danish. His name never transpired, but we learnt that as soon as the news reached him that an English party had landed and started for 'Reykir,' he had saddled a pony and ridden after us, wanting to see what we were like, and also to endeavour to make our acquaintance, and thus be able to air his English with English people, for until then he had never spoken it except with his teacher. My fall gave him the opportunity he wanted, as he was then able to offer his services without intrusion, which he did with the politest manners.

The Icelanders are a wonderfully well-educated people. Our new friend told us he did not believe there was a man or woman in the Island who could not read and write, and certainly on our visits to the various farm-houses, we never failed to notice a Lutheran Bible, and many of the old 'Sagas,' by native poets, beside translations of such works as Shakespear, Göethe, John Stuart Mill's 'Political Economy,' and other well-known writings.

Icelandic is the oldest of the present German dialects, being purer than the Norwegian of to-day, and its literature dates from 1057, immediately after the introduction of writing.

The literature has been ascertained to be of so deeply interesting a character, that the fact of establishing an 'Icelandic Chair' in one of our Universities is now, I believe, under consideration. Many of the natives speak, and understand, Danish – indeed the laws are read to them in that language; and between Danish and Icelandic, we ladies succeeded in making our German understood. Icelandic is now given with English and Anglo-Saxon as optional subjects for the examination at Cambridge for the Modern Language Tripos.

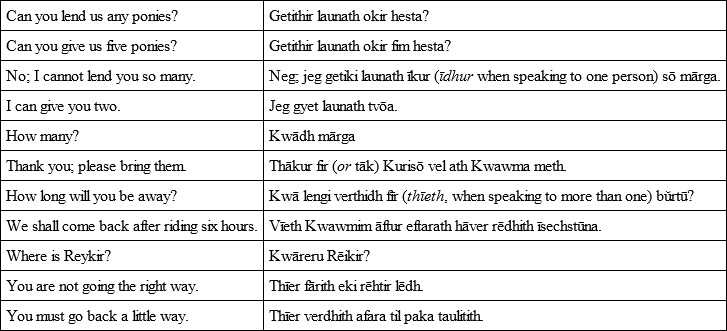

Appended are a few Icelandic sentences, which we found useful in our travels. They are spelt phonetically, as we learnt a few phrases from such of the guides as could speak a little English.

G. C. Locke, in his most interesting work 'The Home of the Eddas,' in speaking of Icelandic literature, says, 'Might not some of the hours so fruitlessly spent in misinterpreting incomprehensible Horace be more fitly devoted to the classics of Northern Europe?.. Snovri Sturluson the author of the "Elder Edda," has no compeer in Europe.'

Our young Icelandic student was very proud of the native Sagas, and justly so. They are works highly esteemed, and of interest to the scholar, embodying the history of the Island, tales of its former chiefs, their laws, their feuds, their adoption of Christianity, the sittings of the Althing, great volcanic eruptions, handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation, until the pastors and learned men committed them to manuscript. They are also full of the most romantic adventures, stirring incidents, and courageous assaults, dear to the heart of every Icelander, and treasured by them as a record of their country's history and its people's hardihood.

CHAPTER VII.

REYKIR

On arriving at Reykir, our guide conducted us to his own dwelling, a fair-sized farm, where he and his wife resided with all their mutual relations, this being the custom in Iceland. In this case they included the wife, her father, mother, grandfather, and sister on the one side; the husband, his two brothers, sister, and mother on the other. Quite a happy little community, as the couple themselves were also blessed with several children.

On entering we were shown into the guest chamber, a small, neatly-furnished apartment, panelled with wood, and containing two windows, neither of which were made to open – a peculiarity not only to be found in Iceland but in some other places, especially in Tyrol. A wooden bedstead stood in one corner, covered with an elaborate patch-work quilt, whilst a table and two chairs constituted the remainder of the furniture. As our party numbered five, some pack boxes were added – not very soft seats after a long jolting ride. A looking-glass hung on the wall; but what a glass! It was quite impossible to recognise your own face in it; I can only liken its reflection to what one would see in a kitchen spoon – not a silver spoon – for there the features, though distorted, would be visible, here they were not. Certainly if such mirrors are the only medium of reflection the people of Reyker possess, they will not grow vain of their personal attractions. The room also contained a barometer and an accordion. In most of the houses we entered we found the latter instrument, which the people, being fond of music, amuse themselves with during the long winter evenings. Curiously enough, there is little or no native music, however. A bookcase on the wall contained quite a small library of Icelandic literature.

Tired with our long ride, we were very glad to rest awhile, while our student friend, our guide, and all the combined families in the house down to the babies and the dogs, stood around us, until the room was so full I don't think another soul could have found entrance.

The Icelanders are on first acquaintance with strangers somewhat reserved; but if treated affably this reserve soon wears off, and their hospitality is unbounded. Even among the poorest a night's lodging is never refused to a traveller.

In outlying districts the farmhouses take the place of inns, whilst the charges are on a most moderate scale.

We brought with us some cheese and biscuits, and a pound of Buzzard's chocolate, which the farmer's wife supplemented with coffee and 'skyr,' the latter served in soup plates.

Skyr is the national dish, taking the place of porridge to a Scotchman, and is nothing less than curded sheep's milk, like German 'dicke-milch,' eaten with sugar, to which cream is added as a luxury. As it was rather sour, we fought shy of it at first, fearing future consequences, but this was unnecessary. It is really excellent, and the natives eat it in large quantities. Huge barrels of this skyr are made during the time the sheep are in full milk, and stored away for winter's use. It is agreeable to the taste, satisfying, and wholesome.

While eating our lunch, our host and his numerous family circle – who all seemed much interested at our presence – did nothing but ply us with continual questions about England, the English people, and the cost of the various articles we either wore or carried with us.

We invited our host and one or two of his friends to taste our cheese and chocolate, when after every mouthful they each shook hands with all the gentlemen of our party; whilst those of the women who shared our repast, after shaking hands with the gentlemen, kissed Miss T. and myself most affectionately.

Class distinction is unknown in Iceland; in fact, there are no gentry, in our acceptation of the term, and little or no wealth among the inhabitants.

I believe the Bishop is the richest man in the Island, and his income is about £150 a year, a sum which these simple-minded folk look upon as riches.

Our coffee and skyr, with attendance for seven people, cost 1s. 7½d., a sum reasonable enough to meet any traveller's purse.

At the ports, however, in Iceland as elsewhere, we found we had to keep our wits about us to avoid being cheated, the English being credited as made of money.

Near to this farmhouse, at Reykir, there were some hot springs which we visited, and we stood and watched with much interest the water bubbling up to the surface.

Close to one of these springs we noticed a large open tub in which the family washing was being done in the natural hot water thus supplied; but the water was yellow, and gave off a sulphureous odour – although it did not seem to discolour the clothes.

The ground around the house was, as usual, piled up with dried fish. It is difficult to realise the stench caused by this food supply, unless one has experienced it. Cod liver oil is made in large quantities in Iceland, and exported to England, where it is then refined for use. If a lover of cod liver oil – and I believe such eccentric persons exist – could once be placed within 500 yards of its manufacture, I feel sure they would never taste it again.

Our guide was one of the largest farmers in Iceland, and owned the adjoining island, namely, 'Lonely Island,' or 'Drangey,' famous as the retreat of the outlawed hero of the 'Gretter-Saga.' The legend states that one Christmas night the chief's fire went out, and having no means of rekindling it, he swam from Drangey Island to the Reykir farm to get a light, a distance which to us, humanly speaking, seems impossible for any man to have done.

The tale goes on to say that an old witch went out in a boat to visit Gretter on Drangey. The boat upset and she was drowned; but a large rock like a boat in full sail rose from the sea a few yards from the Island itself.

The 'Saga' contains many wonderful tales in connection with this locality, specially relative to the high table-land which rises almost perpendicularly above the sea. The scenery in this part of the Island is very fine. On the west side of the 'Skagaffiryr,' a fair-sized river, are seen the peaks of the 'Tindastoll,' a very steep range of mountains intersected with water-worn gorges; while opposite, 'Malmey,' or 'Sandstone Isle,' juts into the sea, north of a rude peninsula with a low isthmus that appears almost like an island.

In the middle of this fjord Drangey is situated. This island, which was the property of our guide, is a huge mass of rock, nearly perpendicular, while at one end is the witch's rock resembling the ship in full sail. Drangey is the home of innumerable eider-ducks, who swim at will in and about the surrounding waters. The drake is a very handsome bird, a large portion of his plumage being white; the hen is smaller, and brown in colour. In disposition the birds are very shy and retiring. The hen builds her nest with down plucked from her own breast; this nest the farmer immediately takes possession of; the poor bird makes a second in like manner, which is likewise confiscated; the third nest he leaves untouched, for by this time the bird's breast is almost bare. Eider-down is very valuable, fetching from 12s. to 20s. per pound. When the farmer desires to catch the eider-duck, he places on the shore, at low water, a small board, carefully set with a series of snares on its surface, and as the birds walk over it they are made prisoners by their feet. There must have been many thousands of eider-duck between Reykir and Drangey, and no gun is allowed to be fired for miles around.

Owing to the uneven nature of the ground, caused by constant earth mounds, even where the soil is good the plough is used with great difficulty. In fact, it can only be utilised by removing the sod and levelling the earth with a spade, until smooth enough for a pony to drag the plough over it. There are very few ploughs, or indeed any farming implements of any size in Iceland, the farmers being too poor to buy them, nor are the latter at all an enterprising class, contenting themselves with the primitive method of cultivating the soil which their forefathers used to adopt. Our guide being a man of more energy than his brethren, and wealthier, had invested in a plough, of which he was very proud, and exhibited to us as a great novelty, evidently thinking we had never seen such a wonderful thing.

Hay was being cut all the time we were in the Island, cut under every possible disadvantage, and yet cut with marvellous persistency. With this labour, of course, the frost mounds interfere, being most disastrous to the scythe, and yet the natives never leave a single blade of grass, cutting round and round, and between these curious little hillocks. On the hay crop so very much depends, for when that fails, ponies die, sheep and cattle have to be killed and the meat preserved, and the farmer is nearly ruined. Hay is therefore looked upon as a treasure to its possessor, and is most carefully stored for the cattle's winter provender; but as during the greater part of the year the Icelanders are snowed up, the cultivation of hay or cereals is a difficult matter.

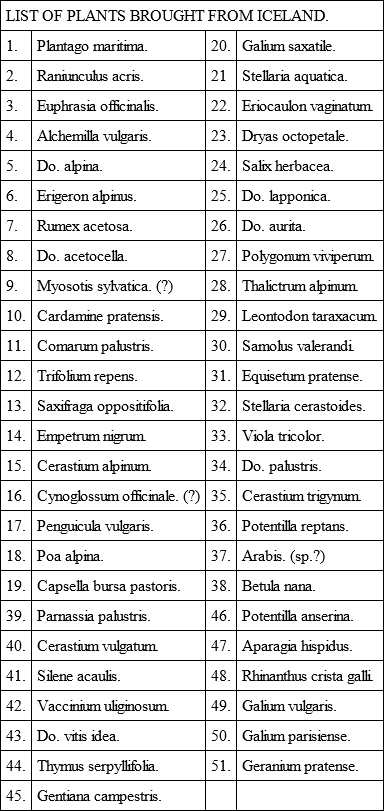

In many parts of Iceland there exist enormous stretches of country covered with dangerous bog, which are, of course, at present undrained. Now, however, that an Agricultural College has been established in the Island, it is hoped a fresh impetus will be given to farming operations in general. At present there are only about 220 acres under cereal cultivation, whilst its inhabitants number over 70,000! Although there are no trees, as before said, there is no scarcity of flowers, indeed the flora is particularly rich, in some instances being composed of specimens not found elsewhere. Often for miles the ground is thickly carpeted with the most beautiful mountain and Arctic flowers, sometimes nestling even in the snow, which lies in patches quite near to the towns. Iceland moss is found on the lava plains.

Mr Gordon was a botanist, and brought home a large collection of specimens; many more, on which he had set great store, were unfortunately lost from the pony's back. The following is a list of those he secured, a great number of which we found growing among huge boulders in high barren places.

Mushrooms grow abundantly in Iceland, and we much enjoyed them, eaten with salt, as a supplement to our meals.

After some hours' rest at Reykir, we remounted, and rode back to Sauderkrok, parting with much regret from our student friend, who had proved a most agreeable and intelligent addition to our party.

That night we were none of us sorry to exchange our saddles for our berths in the Camoens, having been on horseback the greater part of the day, on a road the roughness of which is indescribable.

A further steam of twelve hours up the Hruta Fjord brought us to Bordeyri, a still smaller place than Sauderkrok. Here our captain informed us he should have to wait thirty-six hours for the discharge of further cargo. This fjord is very dangerous, for it has never been surveyed, consequently deep-sea leads were frequently used, the sailors meanwhile chanting a very pretty refrain. When we anchored opposite Bordeyri, we all noticed the anxious look which the captain's face had lately worn had left him, and how pleased he seemed to have brought his steamer safely to her moorings.

We landed in a boat which came alongside the Camoens, and commenced at once to take a survey of the place. A few dozen houses or so, with a large store, where every necessary of life was supposed to be procurable (at least an Icelander's necessities), constituted the town. We entered the store in search of some native curiosities to carry home. A brisk trade was being carried on in sugar candy, large sacks of which were purchased by the farmers, who had come to meet the steamer and barter their goods for winter supplies. Never was any shopping done under greater difficulties than our own, and we almost despaired of making ourselves understood. The store-man, however, grinned most good-naturedly when we failed to do so, and we at last unearthed some finely-carved drinking-horns, and a couple of powder flasks, which we thought would help to decorate a London hall.