полная версия

полная версияA Girl's Ride in Iceland

After dinner, we visited the small Lutheran Church. Unfortunately we had no opportunity of attending a service, though, to judge from the plainness of the ecclesiastical buildings, such must be very simple. The clergyman wears a black gown, and an enormous white Elizabethan frill, with a tight-fitting black cap. This little church accommodates about 100 persons, and in place of pews, has merely wooden forms. Over the altar was an old painting of the crucifixion, done by a native artist, and surrounded by a little rail. The walls were plainly whitewashed, the windows bare, and no musical instrument was visible. There was, however, both a font and a pulpit.

The town boasts of a hospital, a free library, and two printing establishments. At night we returned to our ship quarters.

The next day, there being nothing more to be seen in Akureyri, we decided to take a ride, in order to visit a waterfall, which Mr Stephenson told us would repay the fatigue, and also give us some idea of what an Icelandic expedition was like. Truly that first ride is a never-to-be-forgotten experience. Our road lay over rough stones, and 'frost-mounds.' These latter are a recognised feature in Icelandic travel; they are small earth hillocks, about 2½ feet wide and 2 feet high, caused, according to Professor Geikie, by the action of the frost. In some parts these mounds cover the ground, lying close to each other, so as to leave little or no room for the ponies to step between, and they have to walk over them, a movement which sways the rider from side to side, causing many a tumble even to experienced native horsemen. It is like riding over a country graveyard,

'Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap.'

As to road, there was none, nor is there such a thing in Iceland worthy of the name. The rider merely turns his pony's head in the direction he wishes to go, and it picks its own way far better than he could guide it. The bridle used is a curious workmanship of knotted rope or thick string with a brass curb or bit, ornamented by some queer head or device. The saddles are equally quaint. Those of the women I have already described; those of the men are made very high, both in front and behind, somewhat like a Mexican saddle, there being a hollow in the centre. A crupper is always used, and straps are attached to the back of the saddle, from which the farmer hangs his sealskin bags, containing an omnium gatherum of his lighter goods.

The ponies are very slightly girthed, nor, indeed, would it do to tighten them, so old and rotten is the usual paraphernalia for their equipment that an attempt in this direction would bring the whole thing to grief, which species of contretemps we met with more than once during our rides. In fact, a small English side-saddle and bridle would be not only a most useful addition to a lady's luggage, but add much to her safety and comfort.

While at Akureyri, Mr Stephenson kindly lent us two ladies' saddles, or we should never have accomplished that first ride. They were old-fashioned two-pommeled ones, with gorgeously-embroidered cushions, on which we were supposed to sit, and marvellous saddle-cloths; and we realised we were travellers in earnest when once we mounted and started. Icelandic ponies walk well, and are also trained to pace, a movement closely resembling that of an American runner. This is a motion which requires experience, as it is too quick to rise without practice, and too rough to sit still in the saddle. Some of the ponies trotted, others cantered well, but one had to make them understand one wanted them to do so, as the usual Icelandic mode of riding is that of 'pacing,' at which the animals continue for hours. Later in our trip, when we visited the Geysers, we had to ride over 40 miles a day, in order to cover the distance in time to catch our steamer on its return voyage, and thus became well acquainted with pony riding in all its various modes of procedure.

It did not take us long to reach the Gléra waterfall, which was very pretty, about a mile from the fjord, and formed by the river: trout can sometimes be caught in the pool beneath the fosse.

Perhaps the most noticeable feature of Akureyri was the shark oil manufactory between that little town and Oddeyri, the stench of which was something so fearful that I know of nothing that could possibly compare with it. In certain winds it can be smelt for miles. The manufacture of cod liver oil is bad enough, but that of shark oil is even worse. Luckily, the establishments where such oil is made are not numerous, and are principally confined to such out-of-the-way regions as Iceland and Greenland.

At Oddeyri there was another store of great importance to the natives, viz., a large meat preserving place, where great preparations were in active progress for the coming winter.

Not far distant from here lives a very remarkable man, a self-taught artist of considerable power, who has never been out of the Island, consequently has but rarely seen a picture, and yet his artistic instincts and power of representation are of no mean order; and more especially displayed in his altar pieces. I wonder what he would say to those of Rubens or Vandyck! This man has the greatest love of animals, and was surrounded, when we visited him, by a number of dogs of the Icelandic breed, small animals closely resembling the Pomeranian, with long coats and sharp stand-up ears, which always give a knowing look to the canine head. Most of them seemed to be black, though not a few were a rich sable brown. They are pretty beasts. I don't believe there is a cat in the Island, leastways we never saw one, wild or tame, during our sojourn there. The domesticated cat, fowls, and pigs are practically unknown in these climes.

Some 20 miles from Akureyri once lived another interesting man, Sira Jon Thorlackson, a wellknown native poet, many of whose verses are dear to his countrymen; in his lifetime he undertook and accomplished a translation of Milton's 'Paradise Lost'

There are some 20,000 specimens of butterflies scattered over the world, and yet in Iceland these species are unknown, although insects of certain kinds do exist, especially mosquitos, as we learnt to our cost. Although there are no butterflies, and but few insects, flowers abound.

An Agricultural College has lately been established in the vicinity of Akureyri, the headmaster having formerly been one of the librarians of the Advocates' Library in Edinburgh. No doubt the natives will learn to drain their bogs and swamps, level their frost mounds, and produce more out of the earth than at present, with the help of this much needed institution.

How terribly soon that curse of modern civilisation, drunkenness, spreads! It was Sunday when we first landed at Akureyri, and I am sorry to say not a few of its inhabitants had imbibed more corn brandy than was good for them; it seemed to have the effect of making them maudlingly affectionate, or else anxious to wrestle with everybody.

The two days the Camoens lay off Akureyri gave us no time for prolonged excursions, but was more than sufficient to lionise the little town, so we were not sorry when the steamer's whistle summoned us to return to our floating home.

Ten hours' further journey and our anchor was dropped opposite Sauderkrok, an even smaller town than Akureyri, with its 1000 inhabitants, but which interested us more from its very primitive population, If the reader will follow the steamer's course in the map, he will find Sauderkrok marked in its direct course.

CHAPTER V.

HISTORICAL NOTES

Before proceeding to narrate more of our own experiences of Iceland, I have ventured to collate the following memoranda of the early history of the Island, from Mr George Lock's, F.R.G.S., 'Guide to Iceland,' a most valuable appendage to a traveller's luggage in that Island; the few notes gathered from its pages and other guide-books will enable my readers to follow my narrative with greater interest; whilst I trust this open acknowledgment of my piracy will be forgiven.

It has been ascertained that before the year 874 Iceland was almost an uninhabited Island, being occupied only by a few natives, Culdee Monks, who having seceded from the Roman Catholic faith, retired there for safety and quiet.

Prior to its settlement it was circumnavigated by a Swede, who landed, it is said, and wintered there, and in 868, Flóki Vilgertharsson, a mighty Viking, visited it, who gave it the present name of Iceland.

The first permanent settlers were of the Norse race; two men who, banished from their country, fitted out a ship and sailed to Iceland, where in 874 they made a settlement in the south of the island.

Later Harold Haarfager, a tyrannical and warlike spirit, who was fast extending his kingdom over Norway, so offended many of his subjects, among them several powerful chiefs, that the latter, to avoid further warfare, quitted the land of their birth, and went to settle in Iceland.

This emigration in due time peopled it, until sixty years later its population was calculated at 50,000, which has now increased to 72,000. Most of the settlers came from Norway, supplemented by a few from the Orkneys, Scotland, and Ireland. One of the fjords bears the name of 'Patrick's Fjord,' after an Irish Bishop.

The climate of Iceland at this early date seems to have been a far more moderate one than at the present time, a fact established by scientific research.

In the early days of the Island, the Norse chiefs who took possession of it appropriated to themselves large tracts of country, distributing them among their own retainers; these latter in return swore allegiance to their separate chiefs, undertaking to support them in their private quarrels, whilst they were themselves in this manner protected from aggression.

Every Norse chieftain of any note established a 'Hof' or Temple in his own lands, whilst the yearly sacrificial feasts were supported by a tax gathered from the people. Each chief reigned supreme within his own jurisdiction, and could take life or confiscate property at will. At given periods these feudal rulers met to discuss affairs of importance, or to promulgate laws for the better government of the community; but they had no written laws, or any general accepted body of lawgivers, hence, as may easily be supposed, constant differences of opinion existed, which per force was settled by an appeal to arms. Such a state of things, where 'might became right,' could not continue long amid such a warlike nation as the Norsemen, and in 926 the principal chiefs of the Island took steps to form a Commonwealth, and established a code of laws for its government. It was for some time a question where this primitive national assembly should meet, and finally a rocky enclosure, situated in a sunken plain, cut off by deep rifts from the surrounding country, was selected. This spot, so romantic in position, so safe from intrusion, so associated with the early government of the Island, was called 'Thingfield,' or 'speaking place' – Thingvaller it is now termed – and here the first Althing was held in 929; at the same period 'Logmen' or law-givers were appointed, to whom universal reference on legal questions was referred.

This 'Althing' combined both the power of a High Parliament and that of a Court of Justice, and before the introduction of Christianity into the Island, its members were called upon to swear upon a sacred ring, brought for the purpose from the temple of the High Priest, to administer both 'with justice and clemency.'

About the time William of Normandy invaded England, Godred Crovan, son of Harold the Black of Iceland, conquered the Isle of Man, in whose family it remained for some centuries. Probably through this Norse connection the custom of proclaiming the laws to the people in this latter Isle from a hill in the open air was first introduced, although now discarded by the Althing in Iceland and in various Northern Isles. In the Isle of Man the laws are still read to the people on 5th July on Tynwald Hill; of late years they have only been read in English, but until 1865 they were also proclaimed in the Manx language (which is nearly related to Gaelic), many of the natives not speaking or even understanding English.

According to Joseph Train's 'Historical Notes on the Isle of Man,' 'the great annual assembly of the Islanders at the Tynwald Hill, on the Feast day of St John the Baptist, is thus described in the Statute Book, – "Our doughtful and gracious Lord, this is the Constitution of old time, the which we have given in our days: First, you shall come thither in your Royal Array, as a King ought to do, by the Prerogatives and Royalties of the Land of Mann; and upon the Hill of Tynwald sitt in a chaire, covered with the royall cloath and cushions, and your visage unto the east, and your sword before you, holden with the point upwards; your barrons in the third degree sitting beside you, and your beneficed men and your Deemsters before you sitting; and your Clarke, Knights, Esquires, and Yeomen, and yeoman about you in the third degree; and the worthiest man in your Land (these are the twenty-four Keys) to be called in before your Deemsters, if you will ask any Thing of them, and to hear the Government of your Land and your will; and the Commons to stand without the circle of the Hill with three Clarkes in their surplisses."'

Even at the present day this ceremony continues in the Isle of Man, as above said. When the officials arrive at the Tynwald Hill, the Governor and Bishops take their seats, surrounded by the Council and the Keys, the people being assembled on the outside to listen.

From the establishment of the Althing until the 11th century, the Icelanders seem to have managed their internal affairs with moderation and discretion; at least little of importance connected with the Island is recorded until the discovery of Greenland by Eric the Red, which subsequently led to that of America, towards the end of the 10th century, by Biono Herioljorm, and before the time of Columbus.

CHRONOLOGICAL DATESColonised, 874.

First Althing sat, 929.

Christianity introduced, 1000.

Snorri Sturlusson murdered, 1241, 22d Sept.

Had a republic and a flourishing literature, till subjected to Hakon, King of Norway, 1264. Iceland fell under Danish rule, 1380.

Protestantism (Lutheranism) introduced about 1551.

Famine through failure of crops, 1753-54.

Greatest volcanic eruptions, 1783.

New Constitution signed by the King Christian of Denmark on his visit to Iceland when the 1000th anniversary of the colonisation of Iceland was celebrated, 1874, 1 Aug.

Eruption of 1783 destroyed 10,000 men.

" " 28,000 ponies.

" " 11,500 cows.

" " 200,000 sheep.

Latest great eruption 1875.

The following curious custom is copied from Dr Kneeland's book: —

'In their pagan age, it was the custom for the father to determine, as soon as a child was born, whether it should be exposed to death or brought up; and this not because the rearing of a deformed or weak child would deteriorate a race which prided itself on strength and courage, but from the inability of the parents, from poverty, to bring up their offspring. The newly born child was laid on the ground, and there remained untouched until its fate was decided by the father or nearest male relative; if it was to live, it was taken up and carried to the father, who, by placing it in his arms, or covering it with his cloak, made himself publicly responsible for its maintenance. It was then sprinkled with water, and named. This was regarded in pagan times as sacred as the rite of baptism by Christians, and after its performance it was murder to expose it… The usual mode of desertion was either to place the infant in a covered grave, and there leave it to die, or to expose it in some lonely spot, where wild animals would not be likely to find it. After the introduction of Christianity, such exposure was permitted only in cases of extreme deformity.'

In 997, the first Christian missionary, Thangbrand, landed in Iceland, and preached Christianity to its inhabitants by fire and sword; but the severity with which he tried to enforce his views, failed to convince the people to give up Paganism. Two years later, however, Iceland threw off the heathen yoke, and embraced the Roman Catholic religion. Early in the 11th century, several Icelanders visited Europe to study in its various universities, whilst churches and schools were established in the Island, taught by native bishops and teachers, and with such marvellous rapidity did education spread among the people, that it reached its culminating point in the 13th century, when the literary productions of the Icelanders became renowned through Europe during what was termed the Dark Ages.

'Iceland shone with glorious lore renowned,A northern light when all was gloom around.Montgomery.Towards the end of the 12th century the peace of Iceland was broken up by internal struggles for power, which resulted in the loss of its independence. So wide-spread, in fact, had become these internal feuds, that at last some of the chiefs, refusing to submit to have their differences settled by the laws of the country, visited Norway, and solicited the help of its king, Hakon the Old.

Now this king had long been ambitious to annex Iceland to his dominions, and in lieu of settling the disputes brought before him, by an amicable arrangement between the Icelandic chiefs, he only fomented their quarrels, and finally persuaded a number of them to place Iceland under his sceptre. This they agreed to do, and, after much bloodshed, in 1264 Iceland was annexed to Norway, and its far-famed little republic became extinct.

The history of the Island since that date has been a mournful one. Until thirty years since, the conquest of their Island by Norway, left in its train nothing but apathy and discontent among its inhabitants; in fact, the poor Icelanders, when once they realised their loss of independence, seemed to have neither spirit nor power to rise above the state of suicidal slavery into which they had fallen through their political differences.

In 1848, however, an heroic band of patriots combined, and fought bravely to rescue their country from the degrading condition into which it had fallen; but its long subjection to a foreign yoke has left, it is feared, a lasting impression on the character of its inhabitants, and this, combined with their great poverty, has engendered a sadness and soberness of spirit which they seem unable to overcome.

In 1830, Norway was united to Denmark, and Iceland was transferred to the Danish crown. In 1851 the Icelanders threw off the Roman Catholic supremacy, and embraced the Lutheran form of worship.

In 1800 their time-honoured institution, viz., 'The Althing,' was done away with, and for the subsequent forty-three years Danish rule prevailed. In 1843, however, the former state of government was re-established, but only in a very limited form, the power granted to it being but a shadow of its former self, whilst its sittings were removed from the rocky fortress where it had so long held sway, to the capital, Reykjavik, a large stone building having been erected for its deliberations.

In 1848, when Denmark proclaimed its Constitution, the Icelanders in a body petitioned that the full power of the Althing should be restored. For many years this petition was presented in vain, until King Christian visited the Island, signed a new and separate Constitution for Iceland in January 1873, at the same time retaining certain prerogatives.

In size Iceland is somewhat larger than Ireland, its area being calculated at 38,000 square miles. Geographically it lies south of the south of the Arctic Circle, about 650 miles north-west of Duncansby Head. Its eastern, northern, and north-western coasts are deeply indented with a number of narrow fjords, whilst the southern coast, on the contrary, has not a bay or fjord capable of affording a harbour to even a small vessel.

A group of islands, called Westmannaggar, or Irishmen's Isles, lie off the south coast, and in the various bays on its western coast are innumerable smaller islets.

The interior of the Island is mostly a broad barren plateau, from which rise ice-clad mountains and sleeping volcanoes. Its inhabited regions lie along the coast, where there are small tracts which repay cultivation. The area of the lava deserts, viz., tracts of country covered with lava which has flowed down from volcanic mountains, is computed at 2400 square miles, whilst there are 5000 square miles of vast stony uncultivated wastes – nearly one seventh of the entire area – which apparently increase in extent.

The Island consists of 'Toklar,' or glaciers, and coned heights known as 'Vatna Toklar,' 'Läng Tökull,' 'Dranga,' and 'Glamu Toklar,' and a group of mountains called 'Töklar Guny' in the south of the Island.

The area of pasture land all over Iceland is estimated at 15,000 English miles, but a large part of this is moorland, whilst, sad to say, the pasture land is visibly diminishing, and the sandy wastes increasing. This, to a certain extent, is due to the want of industry of the natives.

In 1875 no less than 1000 square miles was buried beneath an eruption of pumice, but it is considered that the action of the frost and rain upon this porous substance will eventually fertilise the soil and permit of its cultivation. Iceland is the most volcanic region of the earth.

The Island has four large lakes and innumerable small rivers, none of which are navigable beyond a short distance from the mouth. It is not possible to enter here at large on the volcanic features of the Island, but a short chapter has been appended at the end of the volume touching on the principal volcanoes, their action and eruptions.

CHAPTER VI.

SAUDERKROK – RIDING

At a short distance from shore, Sauderkrok, appeared to us at first a most forlorn-looking little settlement, consisting of some few dozen wooden houses and peat hovels. However, on a closer acquaintance with the place, during the two days the steamer remained in port to enable our captain to unload some 200 tons of cargo, we found plenty of things to interest us in the little town.

There being no warehouses, or even sheds, to store the newly arrived goods, they were piled on the beach, and there sold by auction. It was a most amusing scene, the whole population turning out to witness, or take part in, the bidding for the goods thus sold.

The goods were piled up in a half circle, the auctioneer sitting on a table in the middle, assisted by one or two of the chief town's folk. Outside the circle stood men, women, and children from all surrounding parts of the Island; beyond them again, the patient little ponies waiting for the loads they were to carry off inland. Much of the sale was carried on by barter, a system of trading not wholly comprehensible to us strangers, although we saw the natives offer specimens of what they had to exchange. As onlookers, such a novel exhibition afforded a fine field for the study of Icelandic physiognomy, the expressions of anxiety, pleasure, or disappointment being depicted on their faces when the coveted goods were knocked down to the would-be purchaser, or not. To these poor people this must have been a meeting of the greatest importance, as their winter comforts mostly depended thereon; but such is their habitual apathy, that even this great event caused little outward excitement.

No sooner were the goods purchased, than the ship's crew sorted them out, and with the help of an interpreter they were handed over to their owners, some of whom within a few hours were starting off on their homeward journey; a considerable part of the goods, however, still remained on the shore when we left two days later, the purchasers having arranged to return for future loads.

In 1883 the imports amounted to £337,000, from bread, groceries, wines, beer, spirits, tobacco, and stuffs. Trade has been open to all nations since 1854.

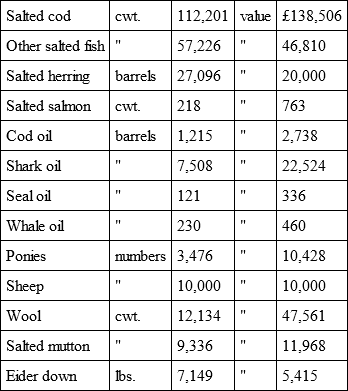

THE EXPORTS OF ICELAND IN 1887

besides woollen stockings and gloves, skins, feathers, tallow, dried fish, sounds, and roes.