полная версия

полная версияNarrative of the Voyages and Services of the Nemesis from 1840 to 1843

The distance of Nankin from Woosung is about one hundred and seventy miles, and a very accurate survey was ultimately completed of this beautiful river, as far as that ancient capital. Even there the river is very broad and the channel deep, so that the Cornwallis was able to lie within one thousand yards of the walls of the city. It is, perhaps, to be regretted that the river was not examined for some distance above the city, for it could not be doubted that, with the assistance of steamers, even large ships would be able to ascend several hundred miles further. But the conclusion of the peace followed so soon after the arrival of our forces before the ancient capital, that there was no opportunity of continuing our discoveries further into the interior, without compromising our character for sincerity, while the negotiations were in progress. It could not have failed, however, had circumstances permitted, of furnishing much interesting information respecting the interior of this extraordinary country.

There are few rivers in the world to be compared with the Yangtze, in point of extent, and the richness of the provinces through which it flows. Supposed to take its rise at a distance of more than three thousand miles from the sea, among the furthest mountains of Thibet, it traverses the whole empire of China from west to east, turning a little to the northward, and is believed to be navigable through the whole of these valuable provinces.69

The navigation of this river was found less difficult than might have been expected. There are, indeed, numerous sand-banks, some of which change their places, owing to the rapidity of the current; and at the upper part of the river, towards Chin-keang-foo, there is some danger from rocks; but the greatest obstacle to the navigation is the rapidity of the current, which, even when beyond the influence of the tide, runs down at the rate of three and a half to four miles an hour. It is not surprising that almost every ship of the squadron should have touched the ground; but, as the bottom was generally soft mud, no serious damage was sustained. The steamers were of course indispensable, and the assistance of two or three of them together was, in some instances, requisite to haul the ships off.

One of the largest transports, the Marion, having the head-quarters and staff on board, was thrown upon the rocks by the force of the current, on the way down from Nankin, and would certainly have been lost, but for the aid rendered by two steamers, the Nemesis and the Memnon, and the valuable experience already gained by the former in the Chinese rivers.

Sir William Parker's arrangements for the merchant transports were perfect; their orders were definite, and were generally obeyed with alacrity; boats were always in readiness, and signals carefully watched. Probably, if it were required to point out any one circumstance which redounded more than another to the honour of the British service, it would be that of having carried a fleet of nearly eighty sail up to the walls of the city of Nankin and brought it safely back again.

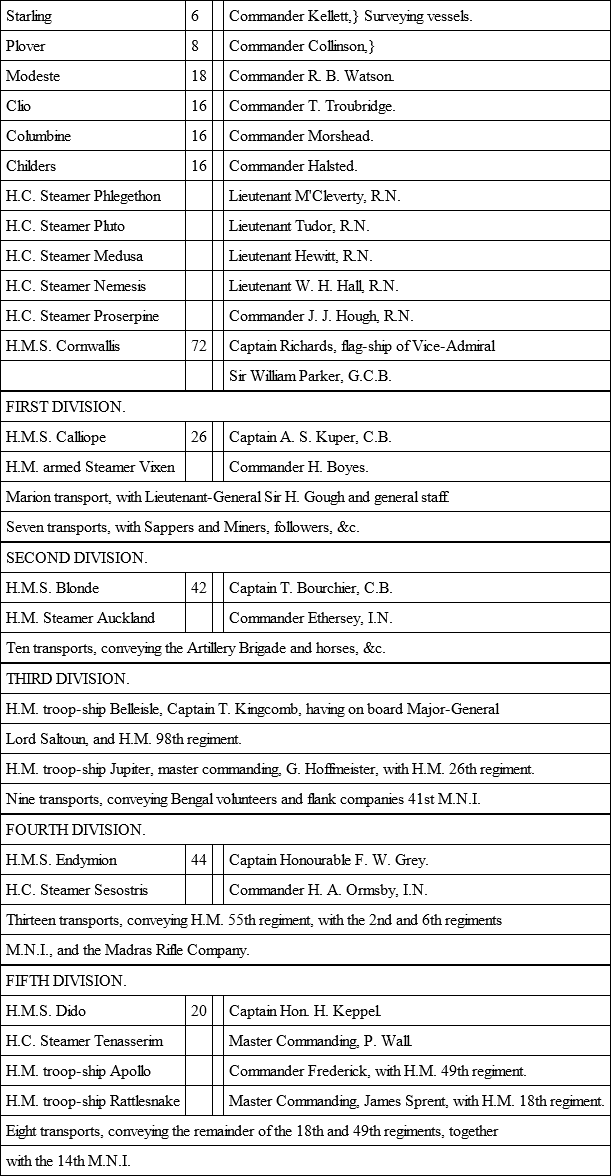

At the beginning of July, the weather became very favourable for the ascent of the river, and the Phlegethon, having returned with the intelligence that a clear and deep channel had been found as far as Golden Island, close to the entrance of the Grand Canal, and that buoys had been laid down to facilitate the navigation, orders were given that the fleet should be in readiness to get under weigh on the morning of the 6th. It was formed into five divisions, each consisting of from eight to twelve transports, conducted by a ship-of-war, and under the orders of her captain; and to each division also a steamer was attached, to render assistance when required.

In addition to the steamers so employed, the Phlegethon, Medusa, and Pluto were in attendance, principally upon the advanced squadron, and in readiness to assist any other ship which stood in need of it. The Nemesis and Proserpine also accompanied the fleet. Thus there were not less than ten steamers attached to the squadron when it set sail from Woosung, and they were afterwards joined up the river (but not until hostilities had ceased) by two other powerful steamers, the Driver and the Memnon.

A list of all her majesty's ships of war and steam vessels, together with those belonging to the East India Company, which were present in the Chinese waters at the conclusion of the peace, will be given in its proper place. The following was the order of sailing of the squadron on leaving Woosung, each division being about two or three miles in advance of the next one. The North Star, Captain Sir E. Home, Bart., was left at Woosung to blockade that river, with orders to detain all merchant junks which might attempt to pass up the Yangtze, or into the Woosung, laden with provisions.

It was a curious sight afterwards to look at the numerous fleet of junks, some of them of large size, which were collected at that anchorage, and for some time it was no easy matter for the North Star to prevent them from attempting to make their escape; but when a round shot or two had been sent through some of the most refractory, and a few of the captains had been brought on board the North Star and strictly warned, they all became "very submissively obedient," and patiently awaited the permission to depart, which was not accorded to them until the peace had been proclaimed.

The advanced squadron consisted of the —

The Chinese had prepared no means of resisting the advance of our squadron up the river; and even the few guns which had previously been mounted on two small forts on the right bank of the river, adjoining the towns of Foushan and Keang-yin, were withdrawn on the approach of our forces, in order to avert the injury which might have been done to those towns had any show of resistance been offered.

The country along the lower part of the Yangtze is altogether alluvial, and intersected by innumerable canals and water-courses. In most parts it is highly cultivated, but in others less so than we were led to expect. On one occasion, I walked for the distance of five or six miles into the interior, attended by crowds of the peasantry, who appeared to be a strong, hardy, well-disposed race, and offered no kind of violence or insult. They appeared to be solely influenced by curiosity, and a few of them brought us poultry for sale, but the greater part seemed afraid to have any dealings with us. The small cotton plant was cultivated very extensively, and at nearly every cottage-door an old woman was seated, either picking the cotton or spinning it into yarn. The hop plant was growing abundantly in a wild state, and was apparently not turned to any use.

The small town of Foushan, at the base of a partially fortified hill, and a conical mountain with a pagoda upon its summit, situated upon the opposite side of the river, form the first striking objects which meet the eye, and relieve the general monotony of the lower part of the river. Above this point, the scenery becomes more interesting, and gradually assumes rather a mountainous character.

Compared with the neighbourhood of Ningpo, or Chapoo, you are inclined to be disappointed in the aspect of the country generally; you find it less carefully and economically cultivated, and perhaps one of your first hasty impressions would be to doubt whether the population of China can be so dense as the best-received accounts lead us to suppose. When you consider the immense extent of country through which this magnificent river flows, and the alluvial nature of the great belt of land which runs along the sea-coast, you are prepared to expect that here, if anywhere, a great mass of people would be congregated, and that town would succeed town, and village follow village, along the whole course of this great artery.

About twenty-five miles above Foushan, stands the rather considerable town of Keang-yin, situated in a very picturesque valley, about a mile distant from the river side; but there is a small village close to the landing-place. The river suddenly becomes narrow at this spot, but soon again spreads out to nearly its former breadth. The town of Keang-yin is distinguished by a remarkable pagoda, to which, with great difficulty, we persuaded a venerable-looking priest to conduct us. He hesitated a long time before he could be induced to lead us into the town, which was surrounded by a very high, thick, parapeted wall, banked up with earth on the inside. No soldiers were to be seen, and many of the inhabitants began very hastily to shut up their shops the moment they saw us enter the streets.

The pagoda appeared to be the only striking object in the place, and from the peculiarity of its construction was well worth seeing. It was built of red brick, in the usual octagonal form, gradually inclining upwards, but was so constructed in the inside, that each story slightly overhung the one below it, although the outside appeared quite regular. The building was partly in ruins, but looked as if it had never been perfectly finished. Not far from it was a well of clear, delicious water, some of which was brought to us in basins, with marks of good-nature, as if the people intended to surprise us with a treat. We afterwards learned that good water is rarely found in the neighbourhood of the river, and that the inhabitants are in the habit of purifying it by dissolving in it a small portion of alum. It was also stated that fish caught in the river are considered unwholesome.

The distance from Keang-yin to Chin-keang-foo is about sixty-six miles by the river, but not much more than half that distance by land, the course of the former being very tortuous. The country gradually increases in interest, becoming more hilly and picturesque the higher you ascend.

At Seshan, which is about fifteen miles below Chin-keang-foo, some show of opposition was offered by two or three small batteries, mounting twenty guns, situated at the foot of a remarkable conical hill. They opened fire at first upon the Pluto and Nemesis steamers, which were at that time employed on the surveying service. The day afterwards they opened fire also upon the Phlegethon and Modeste, which were sent forward to attack them. The garrison were, however, soon driven out, and could be seen throwing off their outer wadded jackets, to enable them to escape with greater nimbleness. The guns, magazines, and barracks, were destroyed.

A little way below Chin-keang-foo, the channel is much narrowed by the island of Seung-shan, and the current is consequently extremely rapid, so that the utmost skill and care, aided by a strong breeze, are necessary to enable a vessel to stem the stream and overcome the strength of the eddies and whirlpools. Seung-shan, or Silver Island, is all rocky, but rendered picturesque by the trees which are planted in the hollows. It is devoted to religious purposes, being ornamented with temples, and it was formerly honoured by the visits of the Emperors, to whom it is said still to belong.

Nearly the same description will also apply to Kinshan, or Golden Island, situated higher up the river, nearly opposite the mouth of the Grand Canal. It is distinguished by a pagoda which crowns its summit, and by its numerous yellow tiled temples. The decayed condition of some of the pavilions, and the remnants of former splendour which once decorated their walls, together with the imperial chair itself, ornamented with well-carved dragons all over its back and sides, attest the importance which this island and the environs of the great southern capital possessed in times long past, and the low estate into which this interesting part of the country has fallen since Pekin became the metropolis of China, and the Imperial residence of its Conquerors.

On the 16th, Sir William Parker and Sir Hugh Gough proceeded up the river in H.M. steamer Vixen, followed by the little Medusa, to reconnoitre the approaches to Chin-keang-foo. They passed up above the city without any opposition, approaching very near the entrance of the Imperial Canal, which takes its course close under the city walls. No preparations for resistance were apparent – at least, there were no soldiers visible upon the city walls, and the inhabitants, who came out in great numbers, were evidently attracted only by curiosity. Hence the first impression was, that no resistance would be offered, and the information obtained through the interpreters tended to encourage the same conclusion.

The walls of the city, which is situated on the right bank of the river, were, however, in good repair, and the distance from the river was not too great to enable the ships to bombard it if requisite. But the general feeling was, that the attack (if indeed any resistance at all were offered) was to be left entirely to the military arm of the expedition, the more particularly as the engagement at Woosung had been entirely monopolized by the navy, and an opportunity was desired by the army to achieve for itself similar honours. A second reconnoissance, made from the top of the pagoda on Golden Island, brought to view three encampments on the slope of the hills, a little to the south-west of the city, which rather tended to confirm the impression that the troops had moved out of the town.

The advanced squadron, under Captain Bourchier, had been sent a little higher up, to blockade the entrances of the Grand Canal, and the other water-communications by which the commerce of the interior is maintained. On the 19th, the Cornwallis was enabled to take up a position close off the city, near the southern entrance of the Grand Canal; and on the 20th, the whole of the fleet had assembled in that neighbourhood.

It has been already stated that little or no resistance was expected in the town itself; but the ships might have easily thrown a few shells into it, to make the enemy shew themselves, or have regularly bombarded the place if necessary. It seems, however, to have been settled that it should be altogether a military affair; and with the exception of some boats, which were sent up the canal, and a body of seamen who were landed, and did gallant service under Captain Peter Richards and Captain Watson, the naval branch of the expedition had little to do. From documents subsequently found within the city, it was ascertained that there were actually about two thousand four hundred fighting men within the walls, of whom one thousand two hundred were resident Tartar soldiers, and four hundred Tartars sent from a distant province. Very few guns were mounted, as the greater part of them had been carried down for the defence of Woosung.

Outside the walls there were three encampments, at some distance from the town, in which there was a force altogether of something less than three thousand men, with several guns, and a quantity of ginjals. As the adult Tartar population of every city are, in fact, soldiers by birth, it may be supposed that even those who do not belong to the regular service are always ready to take up arms in defence of their hearths; and in this way some of our men suffered, because they did not know, from their external appearance, which were the ordinary inhabitants, and which were the Tartars.

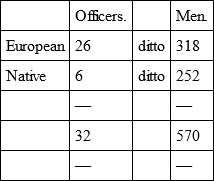

On our side, the whole force engaged at Chin-keang-foo, though very much larger than any hitherto brought into the field in China, did not amount to seven thousand men, including officers, non-commissioned officers, and rank and file. The exact numbers, according to the field list, amounted to six thousand six hundred and sixty-four men, besides officers. They were divided into four brigades.

ARTILLERY BRIGADEUnder Lieutenant-Colonel Montgomerie, C.B., Madras Artillery.

Captain Balfour, M.A., Brigade-Major.

Captain Greenwood, R.A., Commanding Royal Artillery.

Major-General Lord Saltoun, C.B.

Captain Cunynghame, 3rd Buffs, A.D.C.

J. Hope Grant, 9th Lancers, Brigade-Major.

26th Cameronians, Lieutenant-Colonel Pratt.

98th regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell.

Bengal Volunteers, Lieutenant-Colonel Lloyd.

41st M.N.I. Flank Companies, Major Campbell.

Total, 83 officers. – 2235 other ranks.

SECOND BRIGADEMajor-General Schoedde, 55th.

Captain C. B. Daubeney, 55th, Brigade-Major.

55th regiment, Major Warren.

6th M.N.I. Lieutenant-Colonel Drever.

2nd M.N.I., Lieutenant-Colonel Luard.

Rifles of 36th M.N.I., Captain Simpson.

Total, 60 officers – 1772 other ranks.

THIRD BRIGADEMajor-General Bartley, 49th.

Captain W. P. K. Browne, 49th Brigade-Major.

18th Royal Irish, Major Cowper.

49th regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Stevens.

14th M.N.I., Major Young.

Total, 68 officers – 2087 other ranks.

GENERAL STAFFAides-de-Camp to the General Commanding-in-Chief:

Captain Whittingham, 26th regiment.

Lieutenant Gabbett, Madras Artillery.

Adjutant-General, Lieutenant-Colonel Mountain, 26th.

Assistant ditto, Captain R. Shirreff, 2nd M.N.I.

Deputy Assistant ditto, Lieutenant Heatly, 49th.

Deputy Quartermaster-General, Major Gough.

Field Engineer, Captain Pears, M.E.

Commissary of Ordnance, Lieutenant Barrow.

On the evening of the 20th, all the arrangements were completed for the attack upon the city and upon the encampments beyond it, to take place on the following morning at daylight. It has been already stated, that it was not proposed that the ships should bombard the town; and the only vessel which fired into it was the Auckland steamer, which covered the landing, and threw a few shot and shells into the city. But a body of seamen and marines of the squadron (as will presently be described) took an active share in the work of the day, under Captain Peter Richards and other officers; and Sir William Parker himself accompanied the general, and forced his way with him through the city gate.

The plan adopted by Sir Hugh Gough was to endeavour to cut off the large body of Chinese troops encamped upon the slope of the hills; for which purpose the first and third brigades, together with part of the artillery, were to be landed in the western suburbs of the city, opposite Golden Island, near where a branch of the Grand Canal runs close under the city walls; Lord Saltoun, with the first brigade, was to attack the encampments; while Sir Hugh Gough, in person, with the third brigade and the rest of the artillery, proposed to operate against the west gate, and the western face of the walls.

The second brigade, under Major-General Schoedde, was to land under a bluff point somewhat to the northward of the city, where there were two small hills which commanded the walls on that side. The object was to create a diversion, and draw the attention of the enemy towards that side, while the real attack was to be made upon the western gate, which was to be blown in by powder-bags. General Schoedde was directed to use his own discretion, as to turning his diversion into a real attack, should he think proper to do so.

There was found to be more difficulty in landing the troops than had been expected, many of the transports lying at a considerable distance, and the great strength of the current rendering the operation troublesome and protracted. The first brigade, under Lord Saltoun, succeeded in driving the enemy completely over the hills, after receiving a distant and ineffectual fire as they advanced; but they met with a more determined resistance from a column of the enemy, who were in great danger of being cut off. Several casualties occurred on our side, in this encounter. Upon the walls of the town itself, few soldiers shewed themselves, and the resistance which was soon experienced was not at all expected.

General Schoedde, with a portion of the second brigade, took possession of a joss-house, or temple, upon the hill overlooking the northern and eastern face of the walls, near the river, and there awaited the landing of the rest of his brigade, being received by a spirited fire of guns, ginjals, and matchlocks, which was opened from the city walls; this was returned by a fire of rockets.

As soon as a sufficient force had been collected, the rifles, under Captain Simpson, descended from a small wooded hill which they occupied, and crept up close under the walls, keeping up a well sustained fire upon the Tartars. Major-General Schoedde now gave orders for escalading the wall, although, from its not having been part of the regular plan of attack, only three scaling ladders were provided. The grenadier company of the 55th, with two companies of the 6th Madras Native Infantry, advanced to the escalade, under the command of Brevet-Major Maclean, of the 55th. The first man who mounted the walls was Lieutenant Cuddy, of the 55th, who remained sitting upon the wall, assisting the others to get up, with astonishing coolness. He was shortly afterwards wounded in the foot by a matchlock ball.

The 55th and the 6th Madras Native Infantry vied with each other in gallantly mounting the ladders, together with the rifles; but the Tartars fought desperately. As they retreated along the wall, they made a stand at every defensible point, sheltering themselves behind the large guard stations and watch-boxes, which are found at intervals upon most of the Chinese walls.

Many anecdotes are told by those who were present, of the desperate determination with which the Tartars fought. Many of them rushed upon the bayonets. In some instances, they got within the soldiers' guard, and seizing them by the body, dragged their enemies with themselves over the walls; and in one or two instances succeeded in throwing them over, before they were themselves bayoneted. The Tartars were fine muscular men, and looked the more so from the loose dresses which they wore. They did not shrink from sword combats, or personal encounters of any kind; and had they been armed with weapons similar to those of our own troops, even without much discipline, upon the top of walls where the front is narrow, and the flanks cannot be turned, they would have probably maintained their ground for a much longer time, and perhaps even, until they were attacked by another body in the rear. Major Warren and Captain Simpson were wounded, as well as Lieutenant Cuddy.

As soon as the wall was scaled, one body of our troops proceeded to clear the walls to the right, and the other to the left; and the latter, as they scoured the walls, afterwards fell in with the third brigade, with the General and the Admiral at their head, who had just forced their way in at the gateway. While these important successes had been gained by General Schoedde with the second brigade, two other operations had been conducted at the western gate, one by the third brigade, and the other by a small body of marines and seamen, under Captain Peter Richards. These are now to be detailed.

Sir Hugh Gough, as soon as he had been joined by the 18th and the greater part of the 49th, with the 26th, which had not accompanied Lord Saltoun's brigade, gave orders to blow in the west gate with powder-bags. The canal which runs along the walls on that side was found not to be fordable; and this was ascertained by four officers who volunteered to swim across it to ascertain the fact. Sir Hugh Gough was at this time with the third brigade, under Major-General Bartley, at about midway between the south and west gates, but determined to storm the latter, because the suburbs afforded shelter for the men to approach it, with little exposure. A few Tartar soldiers only appeared upon the walls at this point, as the main body had probably been marched off to reinforce those who were opposed to our troops, after the escalade of the walls on the northern side.

Two guns, under Lieutenant Molesworth, were placed so as to command the approach to the gate, and to cover the advance of a party of sappers and miners, under Captain Pears, who were to fix the powder-bags against the gate. This operation was perfectly successful; and the General, putting himself at the head of the 18th, who had just come up, rushed in over the rubbish, the grenadiers forming the advance, and entered a long archway, which led into what might be called an outwork, from which there was a second gate, conducting into the town itself.

It appears that in Chinese fortifications, as before described, there are always two gateways; the outer one placed at right angles to the main wall of the town, so as to be flanked by it, and leading into a large court, surrounded by walls similar to the walls of the town, and in which there are commonly cells for prisoners, &c. The second gate and archway leads from it directly into the body of the place, and is surmounted by a guard-house upon the top of the gateway, to which you ascend by a flight of stone steps on either side.