Полная версия

The Healthy Thyroid: What you can do to prevent and alleviate thyroid imbalance

Three-quarters of cases of autoimmune disease occur in women. What exactly triggers the immune system in women to attack itself more frequently than in men?

The Family Factor

The tendency for autoimmune diseases to run in families provides one clue. It suggests that a faulty gene or genes may be partly to blame. Indeed, scientists have identified a handful of so-called ‘susceptibility’ genes that render some of us more vulnerable to autoimmune attack. They have also pinpointed several areas – ‘susceptibility regions’ – on chromosomes, the 23 pairs of rod-like structures that carry our genes, that appear to confer a greater risk of autoimmunity.

Many autoimmune diseases, including autoimmune thyroid disease, are strongly associated with a gene for human leukocyte antigens (HLA) found on chromosome 6. Another susceptibility gene, CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-4), is also involved. Both these genes are known as immune-modifying genes – they alter the way in which your immune system behaves. As well as susceptibility genes, researchers are also finding genes that are specifically involved in autoimmune thyroid problems. These ‘thyroid-specific genes’ are thought to work hand-in-hand with susceptibility genes to trigger an autoimmune attack against the thyroid.

As to why women are at greater risk than men, scientists have come up with an intriguing theory that suggests that it may be connected with the continued presence of foreign cells from a fetus in the mother’s bloodstream – and vice versa. Another way to acquire cells that aren’t your own is from a twin, even one you didn’t know you had, because it is now known that a number of pregnancies start out as twin pregnancies, but soon lose one of the embryos. Says Dr J. Lee Nelson, the American scientist who pioneered this theory, ‘Our concept of self has to be modified a little bit. We’re not as completely self as we thought we were.’

Deciphering the Clues

The presence of thyroid autoantibodies in your bloodstream is an important clue that there has been an immune attack on your thyroid. In fact, it was by studying Graves’ disease that scientists acquired some of the earliest clues of what was going on in autoimmunity. The chief culprit in Graves’ disease is an antibody, first discovered in the blood of Graves’ patients as long ago as 1956, dubbed ‘long-active thyroid stimulator’, or ‘LATS’, because in animals, it stimulated thyroid activity for longer than thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Later researchers identified LATS as a type of immunoglobulin G, the main antibody in the bloodstream and, because it stimulates thyroid production by locking onto the TSH receptor, they renamed it TSHR-Ab. This autoantibody is now thought to be responsible for the thyroid overactivity in Graves’ disease, and to play a key role in the development of thyroid eye disease by overstimulating certain cells that line the eye sockets.

A similar process is involved in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis except that, in this case, the rogue antibodies are directed against thyroglobulin (TG), the protein molecule in which thyroid hormone is stored, and thyroid peroxidase (TPO), a key enzyme involved in the early stages of manufacturing thyroid hormone. The autoantibodies block receptors on both TG and TPO, thereby causing underproduction of thyroid hormone.

CHAPTER THREE The Out-of-Balance Thyroid

Given the wide-ranging action of the thyroid, it is hardly surprising that, when something goes wrong, it affects the entire body. Exactly what these effects are depends on whether your thyroid becomes underactive or overactive.

Hypothyroidism, or the underactive thyroid, can produce a long and bewildering list of symptoms (see Table 3.4, page 42). Most of these are non-specific and easily attributable to some other disorder or simply fatigue – one reason why it often takes so long to get a diagnosis. As Camille recalls:

I noticed that my mental energy had gone right down, but I kept rationalizing. The tiredness was dreadful, but I persuaded myself it was because I was overdoing it. I kept saying to myself, ‘If only I’d taken two weeks off at Christmas, I wouldn’t be feeling so tired’. It was only the hair loss that got me in for a test.

Clare has a similar story:

I just thought I was putting on weight. I put on two-and-a-half stone in as many years. Yet, despite going to Weight Watchers and not cheating, I couldn’t shift it. In retrospect, there were other clues. I developed coarse skin but, because I’d had a baby, and my hands were in and out of sterilizing solution, I just thought it was that. My periods were irregular and I was tired all the time, but I put that down to working and having a family. It was sheer vanity that drove me to the surgery in the end.

Jennifer, who developed an underactive thyroid after the birth of her second child, remembers:

My energy levels fluctuated from day to day. I would start the week feeling fine but, by Tuesday, I would be completely exhausted and have to take the day off. I managed to drag myself through Wednesday and Thursday, and Friday I had off. I would spend the weekend in bed. I was so depressed, I would sometimes just lie there and cry. I had constant headaches and sore throats, my muscles ached, my nails were brittle, and I was always getting flu. I couldn’t concentrate; my memory was appalling. I was so cold that, even in the summer, I had to take a hot-water bottle to bed. Our sex life went completely downhill.

The key characteristic of hypothyroidism is that all your systems slow down as a result of metabolism running on near-empty. Your appetite decreases and what you do eat is converted into energy more slowly. You gain weight and feel permanently cold. The smallest task becomes a supreme effort. Your muscles feel weak and stiff, and ache on the slightest exertion. Just walking up the road can leave you exhausted and breathless. You may experience muscle cramps. Your heart beats more slowly and your pulse is slowed while blood pressure rises. Digestion takes longer and you become constipated. You may also experience joint pain and stiffness. Your kidneys work more slowly, leading to water retention and tissue swelling (oedema). Your liver also slows down, resulting in a rise in levels of ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol and other blood fats known as triglycerides. You may succumb to every passing minor infection as the lack of thyroid hormones takes its toll on your immune system. Cuts and bruises take a long time to heal because of the fragility of your blood vessels. You feel miserable, washed out and overwhelmed with fatigue. As Christine observes, ‘It is total; every body system is affected. People often say, “I just feel so ill, but I can’t put my finger on it.”’

Appearance Matters

One of the most distressing aspects of hypothyroidism is the effect on your looks. Even though you have no appetite, the weight piles on unstoppably. Your hair becomes dry, brittle and thin; your skin becomes dry, coarse and puffy. Your waistband nips, your rings become tight and you feel bloated. These symptoms are the result of an autoimmune attack called ‘myxoedema’, where the cells become ‘leaky’, leading to fluid accumulation and mucus deposition beneath the skin. You may become pale due to anaemia, and your complexion may take on a slightly yellowish hue due to the buildup of the yellow pigment beta-carotene in your blood.

Carol, who was initially diagnosed with depression and went for many years before her underactive thyroid was diagnosed, recalls:

I developed nasty sores on my skin, mainly on my arms, but also on my upper thighs, stomach, and neck. It took five years to find out this was a combination of a side-effect from the antidepressants and poor skin-healing due to my thyroid problem.

You may also develop a goitre (see page 56) or, alternatively, your thyroid may shrivel up (atrophy).

Tired All the Time

These physical symptoms are compounded by an almost overwhelming exhaustion, as Maggie, who developed an underactive thyroid after the birth of her first child, relates:

I felt totally paralysed for three days. I was so weak I could barely walk around. That slowly improved, but I still felt slow – the way I imagine an old person must feel. I had no appetite, but even so, the weight piled on. On one occasion, I was actually vomiting for three days and I still put on a pound! I was freezing cold all the time and had to keep the heating turned up high. My face was puffy; I looked as though I had been crying. My head felt as if it was full of cottonwool. I couldn’t focus properly – if I looked at the TV and then tried to look at a newspaper, everything was blurred. I had noises in my ears. I slept very badly. I had pain and tingling in my hands that woke me up. I was also suffering from terrible constipation. I started losing my hair, but I just thought that was the normal hair loss that happens after pregnancy, but what was strange was that I didn’t have to shave my legs or pluck my eyebrows. I felt as if my whole appearance was changing. The smallest task seemed enormous – I had trouble just walking to the corner of the road. Things came to a head when we went for a walk with some friends we were visiting. I was dragging myself along at my usual snail’s pace, several yards behind. Being unable to keep up with the others really brought it home to me that it was more than just the after-effects of having a baby. Something was seriously wrong.

June said, ‘I thought everyone else was going too fast. I didn’t realise it was me that was slow.’

In some cases, the tiredness associated with an underactive thyroid is so troublesome that a number of doctors believe that ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome) and fibromyalgia (pain in the soft tissue and muscles accompanied by exhaustion) may be a result of undiagnosed hypothyroidism. In the absence of hard evidence from studies, there is much debate over this issue. In the US, Dr John Lowe, an expert in fibromyalgia, believes there is a clear link between the two conditions (Clinical Bulletin of Myofascial Therapy, 1997; see also www.thyroid.about.com). In the UK, Dr Charles Shepherd has found that hyper- and hypothyroid problems are associated with ME/CFS. Most conventional doctors tend to pooh-pooh the idea, but many current texts on the thyroid, especially those coming from America, consider the idea to have merit.

The Senses

An underactive thyroid can affect your senses as a result of tissue swelling. You may experience headaches, migraine or blurred vision. You may become slightly deaf or hear constant noises in the ears (tinnitus). Your voice may become deep and husky due to thickening of the vocal cords. Swelling and thickening of the tissues around the wrists and ankles can compress the nerves, causing pins-and-needles in the hands and feet or numbness, a condition known as carpal – tarsal, or carpal tunnel, syndrome. This can make it difficult to use a keyboard or perform other everyday tasks. Thickening of the neck tissue may cause snoring. Digestion may be impaired as the muscular contractions (peristalsis) that propel food through the gastrointestinal tract slow down. Sluggish bowels can cause constipation.

Menstrual Disturbances and Subfertility

Menstrual problems and subfertility – difficulty conceiving and/or maintaining a pregnancy – are both associated with an underactive thyroid (see Chapter 8). It may also be difficult to conceive because your sex life has ground to a halt. When doing anything is an effort, it may be impossible to summon up the energy for sex, especially if you are feeling unattractive due to various physical changes.

If hypothyroidism is a result of pituitary malfunction, you may begin to produce milk from your breasts even though you are not lactating, a result of an abnormal production of the milk-producing hormone prolactin by the pituitary.

Lyn, who was diagnosed with hypothyroidism after the birth of her second baby, says, ‘I was very irritable and my lack of libido didn’t help my marriage.’

Effects on the Heart

One of the most serious consequences of hypothyroidism is that the heart, like every other system in the body, slows down. Sluggish thyroid function causes excess LDL cholesterol to accumulate in the bloodstream, which can lead to atherosclerosis – narrowing and ‘furring’ of the arteries – causing insufficient oxygen to reach the muscles of the heart.

Clues that your heart may be affected include shortness of breath on exertion or, sometimes, chest pain (angina). Another symptom of atherosclerosis is pain in the calf on exertion (intermittent claudication), caused by furred arteries in the leg.

Tests may reveal a slow pulse rate (under 60 beats a minute), unusual in everyone except trained athletes, low blood pressure, unusual in everyone except the very young and/or very fit, and raised levels of ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol and other blood fats called triglycerides.

Mental Effects, Depression and Mood Swings

Mental sluggishness is a commonly reported effect of hypothyroidism. Your brain feels like cottonwool, and you find it difficult to pay attention, to concentrate and to remember. There may be a time lag while you try to recall events, and even familiar names or facts can be elusive – a mental state typically described as ‘feeling in a fog’.

One of the biggest bones of contention is the relationship between thyroid problems, depression and mood swings. In a letter to the British Medical Journal (October 2000), consultant psychiatrist Martin Eales outlined his belief that faulty thyroid function – including so-called mild or subclinical thyroid problems – is a significant factor in triggering depression and the failure of some people to respond to treatment with antidepressants, and can aggravate mood swings in manic-depression (known medically as bipolar disorder). This idea receives some support from the fact that antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, associated with hypothyroidism, have been found in people with manic-depression. In rare instances, there may be more severe mental disturbances, such as paranoia (feelings of persecution). These symptoms – at one time cruelly described as ‘myxoedematous madness’ – quickly disappear once treatment to correct the underactive thyroid is begun.

A Matter of Chemistry

To understand these links, it is necessary to look more closely at the chemistry of the brain and some of the discoveries that have been made concerning how the brain and body ‘talk’ to each other. Depression has been found to be linked to changes in both the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis and the hypo – thalmus – pituitary – adrenal axis – two key hormonal circuits that link the brain and the body.

A major step towards understanding depression came with the discovery that the condition is linked to a shortage of the brain chemical serotonin, sometimes called the ‘happiness hormone’. This led to the development of a new class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which, as the name suggests, selectively block serotonin receptors to cause levels of serotonin – and feelings of wellbeing – to rise. These drugs, of which Prozac is the most well known, are now considered the standard treatment for depression.

Recently, researchers found that people who are depressed tend to have raised levels of thyroxine (T4). At the same time, they have disturbances in their body clock causing lower daytime levels and a lower-than-normal night-time surge of thyroid-stimulating hormone, thought to be due to lack of serotonin. This is yet another example of how the brain and body communicate. Some doctors also suggest that the activity of T3 is also reduced, although this is not as yet supported by any clear evidence.

A number of psychiatrists, particularly in the US, have found that a T3 plus antidepressant ‘cocktail’ helps lift depression faster in the 30–40 per cent of people who seem to be resistant to antidepressants. Interestingly, adding the more usual thyroid treatment, T4, has not proved effective, which suggests that the ability to convert T4 to T3 in the brain may be damaged in depressed people. Although most studies were carried out with the older tricyclic antidepressants that are not as widely used these days, it is thought that adding a dash of T3 to an SSRI might be equally effective.

Sorting It All Out

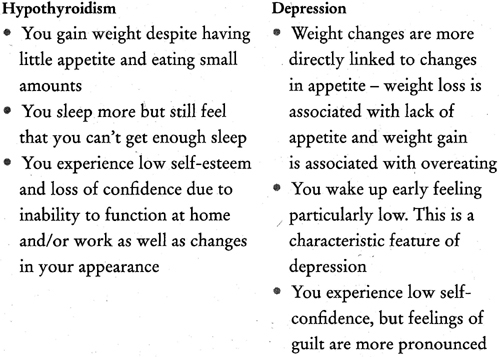

It may not always be easy for you – or your doctor – to distinguish between depression and hypothyroidism because the two conditions have many symptoms in common. In fact, some doctors surmise that an underfunctioning thyroid may be an indicator of depression. Others think that depression can put you more at risk of developing thyroid antibodies by impairing immune function, which may, in turn, lead to hypothyroidism.

Carol’s story is fairly typical:

I felt extremely fatigued, had trouble getting up in the morning and wanted to sleep all day. Sometimes I took a day or two off work and did just that – slept for 24 hours. I was also very tearful and had problems concentrating, making decisions, even thinking. I couldn’t watch TV or read – it was too much effort. I took about three months off work. I had a nice GP at the time and he diagnosed depression. I had a feeling it was something more physical as I didn’t feel depressed in the way it was described in the books. I wanted to do things, but I had no energy. I took antidepressants for five years. They helped my mood, which enabled me to return to work, but I had little energy for anything else.

Table 3.1 Symptoms common to both hypothyroidism and depression

• Feeling miserable and ‘down in the dumps’ • Anxiety • Irritability • Loss of interest or pleasure in things that you used to enjoy, such as sex • Lack of energy • Feeling tired all the time • Weight changes • Appetite changes • Sleep disturbances • Difficulty concentratingTable 3.2 Clues to help you to determine whether you have hypothyroidism or depression

DEPRESSION OR THYROID?

Christine, whose underactive thyroid went undiagnosed for years, urges women not to be fobbed off with a diagnosis of depression if the symptoms don’t improve with antidepressant treatment. She was one of the few who developed myxoedema coma, a potentially life-threatening condition in which body temperature drops severely, brought on by untreated hypothyroidism. It can also cause low blood sugar and seizures, and lead to death. The coma can be triggered by cold, illness, infection or injury, and drugs that suppress the central nervous system. Although rare, it can still happen, as Christine recalls:

After years of to-ing and fro-ing to the doctor, I was referred to a psychiatric unit and diagnosed as chronically depressed. I was prescribed lithium [a drug used to treat manic-depression]. Within six months, I was comatose – my body grinding to a halt and my kidneys failing. I heard the doctors talking outside my room saying it should never have happened.

Although such an occurrence is extremely rare, it does underline the importance of persistence and of getting a proper diagnosis.

Why Does the Thyroid Become Underactive?

There are two main types of hypothyroidism: primary, when the thyroid is the source of problems; and secondary, when a fault in the hypothalamus or pituitary has a knock-on effect on the thyroid.

• Primary hypothyroidism can be brought on by:

• thyroiditis (inflammation of the thyroid), a feature of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (see page 49) and postpartum thyroiditis (PPT)

• surgical or medical treatment for an overactive thyroid (see Chapter 5) or surgery and/or radiotherapy for certain kinds of cancer

• prescription medications and over-the-counter drugs containing iodine (iodides), such as lithium for treating manic-depression, and some cough remedies

• congenital (inborn) problems affecting the thyroid, such as absence or abnormal development of the thyroid or errors of metabolism (see Chapter 9).

• Secondary hypothyroidism is caused by failure of the hypothalamic – pituitary – thyroid hormonal axis leading to deficient secretion of hormones by the hypothalamus or pituitary, caused by:

• known damage to the hypothalamus or pituitary as a result of previous surgery, meningitis, trauma or radiation to the brain

• the development of tumours or cysts.

Variable Symptoms

Although many of the symptoms of an underactive thyroid are common to both primary and secondary hypothyroidism, there are some suggestive differences that either you or your doctor may notice.

Table 3.3Clues to help you determine whether you have primary or secondary hypothyroidism

Primary hypothyroidism Secondary hypothyroidism Periods are likely to be heavier Periods may be absent (amenorrhoea) Skin and hair are coarse Skin and hair are dry; skin may be pale and lacking in pigment Breasts remain normal-sized Breasts may be small and shrunken Heart is enlarged due to pericardial effusion (fluid accumulation in the sac surrounding the heart) Heart is small Blood pressure and blood sugar levels are normal Blood pressure is low, often with low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) due to adrenal insufficiency or a shortage of growth hormoneIs Your Thyroid Underactive?

Symptoms of hypothyroidism are not always easy to detect. Table 3.4 lists some symptoms that you may experience, that others may notice or that your doctor may detect.

Table 3.4 Symptoms suggestive of hypothyroidism

You may experience Anxiety and panic Bloating and fluid retention Blurred vision/difficulty focusing Brittle dry nails Breathlessness/chest pain on exertion Constipation Depression Difficulty in concentrating/conceiving/exercising Discomfort swallowing Dry eyes Dry skin Fatigue Feeling constantly cold Forgetfulness Headaches and migraine Increased infections Joint pain and stiffness Menstrual problems Miscarriage Muscle weakness or stiffness and cramps Sluggish digestion Tingling and numbness in hands and feet (carpal tunnel syndrome) Others might notice You are moody You’ve put on weight You have to peer at a menu to read it You puff and pant when you walk up a hill You seem miserable You don’t seem to be following what they say You’ve lost your enthusiasm You seem unusually irritable You’ve gained weight Your face and eyes appear puffy You’ve started snoring Your skin looks faintly tanned (due to beta-carotene deposited beneath the skin) Your doctor may detect Anaemia Doughy abdomen Goitre Galactorrhoea (milk secretion when you aren’t breastfeeding) due to pituitary dysfunction Loss of muscle power Oedema (swelling) Slowed reflexes Increased pigmentation (due to beta-carotene deposited beneath the skin)