Полная версия

The Healthy Thyroid: What you can do to prevent and alleviate thyroid imbalance

The Healthy Thyroid

What you can do to prevent and alleviate thyroid imbalance

Patsy Westcott

Copyright

Thorsons Element

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

and Thorsons are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published as Thyroid Problems by Thorsons 1995 This revised edition published by Thorsons 2003

© Patsy Westcott 2003

Patsy Westcott asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007146611

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007392001

Version: 2016-02-29

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1 The Hidden Illness

Chapter 2 Understanding Thyroid Problems

Chapter 3 The Out-of-Balance Thyroid

Chapter 4 Getting a Diagnosis

Chapter 5 Treatment Options

Chapter 6 I Just Want to Feel Normal Again

Chapter 7 Integrated Treatment: Complementary Therapies

Chapter 8 The Eyes Have It: Thyroid Eye Disease

Chapter 9 Thyroid Problems and Reproduction

Chapter 10 The Menopause and Beyond

Chapter 11 Questions and Conundrums

Glossary

Resources

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE The Hidden Illness

Thyroid disease is common and affects women more frequently than men.

Many books and articles on thyroid problems for both the general public and medical profession begin with these or similar words. But this bland statement barely begins to suggest the number of women afflicted by thyroid problems or the impact of thyroid disorders on our lives. In fact, according to a review in the British Medical Journal, taken together, underactive and overactive thyroid conditions represent the most common hormonal problem – and this problem overwhelmingly affects women.

In terms of statistics alone, thyroid problems in women deserve to be taken seriously:

• Four out of five people with thyroid disorders are women.

• One in 10 women will develop a thyroid disorder at some stage in her life.

• Between one and two in 100 women in the UK will develop an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism), a condition 10 times more common in women than men.

• Two out of every 25 women – and one in 10 past the menopause – have so-called mild thyroid failure that is considered borderline on blood tests. These ‘subclinical’ problems are linked with nagging ill health, such as fatigue, mood swings and overweight, as well as more serious medical problems such as depression, heart disease and osteoporosis.

• Overactive thyroid conditions (hyperthyroidism) are also common in women, affecting between five in every 1000 to one in 50 – or 10 times more women than men.

• One in every 100 people in the UK will develop an autoimmune thyroid disorder, when the body turns against itself to cause the thyroid to become either underactive or overactive. Autoimmune disorders, including those affecting the thyroid, are estimated to be the third biggest killer after heart disease and cancer.

• Having a personal or family history of autoimmune disorders, such as diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis, gives you a 25 per cent greater risk of developing a thyroid disease than someone without such a history.

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis – an autoimmune disorder causing an underactive thyroid – may account for up to one-third of such cases in this country and is five times more common in women than men.

• Graves’ disease – an autoimmune condition causing an overactive thyroid – is 15 times more likely to affect you if you are a woman.

• Goitre (a swollen or enlarged thyroid gland) is four times more common in women than in men.

• Thyroid nodules or lumps are also more common in women – estimated to affect about one in 20 women.

• Thyroid cancer, although rare, is also more likely to develop if you are a woman.

Only as Healthy as Your Thyroid?

Thyroid problems can affect a woman at any age or stage in life – from the teens to retirement. Throughout this time, they are a source of much ill health and unhappiness. During the reproductive years and after the menopause, they can exacerbate other female health problems as well as create a host of debilitating symptoms that affect every system of the body:

• Thyroid problems can cause menstrual disturbances, such as heavy or absent periods, and worsen problems such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

• Thyroid problems are an underrecognized cause of fertility problems and miscarriage.

• During pregnancy, thyroid disorders are the most common hormonal problem.

• Even a mild shortage of thyroid hormone during pregnancy may affect the unborn child’s future IQ (intelligence quotient). Research shows that children, aged seven to nine, whose mothers had untreated hypothyroidism during pregnancy scored about seven points lower on IQ tests.

• According to US research, women with faulty thyroid function are more likely to give birth to babies with defects of the heart, brain or kidney, or have abnormalities such as a cleft lip or palate, or extra fingers.

• Babies whose mothers have an underactive thyroid have an increased risk of heart problems – even if their mothers are being treated for the condition. Yet, at the time of writing, the NHS still does not routinely test thyroid function in pregnancy.

• One in 10 young women have thyroid problems after giving birth, with symptoms such as depression, tiredness and a lack of zest that cast a shadow over the first months of parenthood. Such symptoms are often misdiagnosed as ‘the baby blues’, thus depriving women of treatment that would help.

• Later in life, thyroid disease becomes even more common. An estimated one in 10 women over 40 may have undiagnosed thyroid disease, which is particularly worrying as thyroid problems are associated with an increased risk of two very significant causes of female ill health in later life: heart disease and osteoporosis (brittle-bone disease).

• One in five women over 60 suffer thyroid problems. With the ‘baby-boomers’ reaching this age, thyroid disorders will become an increasingly major health challenge.

• Thyroid disease in older women is more likely to be ‘silent’, producing few or vague symptoms. But compared with, say, high blood pressure – another ‘silent’ disease with serious consequences – thyroid problems are far less likely to be suspected or tested for.

These facts and figures alone put thyroid disease on a par with conditions like diabetes, estimated to affect one to two in every 100 people, and breast cancer, which strikes one in eight women. However, thyroid problems attract only a fraction of the research funding given to these high-profile conditions, and have until only recently relatively poor media coverage. That this is now beginning to change was reflected by an editorial in the prestigious British medical journal The Lancet that declared ‘you’re only as healthy as your thyroid’.

Are Times Changing?

During the writing of the first edition of this book more than seven years ago, there was little awareness – even among journalists specializing in women’s health – of just how common thyroid problems are and of the misery they can cause. A small request for help placed in The Guardian newspaper resulted in a deluge of phone calls: 200 over two days.

Revisiting thyroid problems now, has anything changed? The good news is that there has been a shift in knowledge and attitudes. A great deal more is becoming understood in terms of how thyroid problems are caused and how they may best be treated. And certainly, many more people are now aware of thyroid disease than in 1995.

Part of this new awareness is thanks to a number of books drawing attention to the wide-ranging effects of thyroid problems and the misery they can cause. The advent of the Internet has also done much to fill the information gap. There are now several excellent websites where women with thyroid problems can get information and communicate with others who have the same condition. This is good news for the millions of women living with a faulty thyroid.

However, in other aspects, the changes have been pitifully few. Thyroid disease is still a ‘Cinderella’ disorder, despite being the cause of so much depression, tiredness, discomfort and feeling well below par. Even nowadays, women often soldier on for long periods before anyone takes their complaints seriously – hardly surprising given that the average medical student only has a lecture or two on thyroid problems, if they’re lucky. And although there are more post-training courses for interested doctors, endocrinology (the study of hormones) is still not a core subject in most basic medical courses.

Like their ‘sisters’ in 1995, many of the women interviewed for this new edition had struggled on for months, even years, with crippling symptoms before being diagnosed. Once diagnosed, they had to cope with unsympathetic doctors and endure treatments that were uncertain, took time to get right and sometimes didn’t work at all.

Just like seven years ago, many women also spoke of the dilemmas posed by treatment – how long it had taken for medications to start working, the uncertainty of their effects, the agony of deciding whether to opt for surgery or radioiodine therapy, or whether different forms of medication might be more effective. All related stories of how difficult it was to obtain relevant information and how alone they felt with this unpredictable disease.

Others told poignant stories of how the disease had affected their daily lives and relationships in the face of the pressures of holding down a job while battling overwhelming fatigue, the difficulties encountered with partners, friends and children who did not always understand why the person they loved had undergone such a major personality change, of being overweight or underweight, of the self-consciousness endured because of bulging eyes, thinning hair and thickened skin, and the effects these had on their self-esteem. Some described the heartache of not being recognized by friends they had not seen for some time.

These physical problems are often dismissed as trivial but, in a world where the pressure to look young and attractive is intense, they can become the cause of a huge amount of distress and self-loathing. They can also lead to other women’s health problems such as eating disorders.

Tip of the Iceberg?

In recent years, it has become apparent that thyroid problems may be even more common than ever imagined. The availability of more sophisticated methods of testing thyroid function has revealed that many seemingly healthy women with apparently normal thyroid function have, in fact, abnormal levels of hormones and antibodies against the thyroid gland. This also suggests that the cases of thyroid disease identified and treated may be only a fraction of what is actually out there.

Since 1995, such cases of mild or low-grade thyroid disease have received a great deal of attention in the medical and public media. Medical journals, such as the influential New England Journal of Medicine, have carried major articles on subclinical thyroid disease, while the shelves of bookshops now carry stacks of books about thyroid problems aimed at the general public. Many put forward the view that hidden thyroid problems are a factor in a host of conditions reaching epidemic proportions in the 21st century, including:

• Chronic fatigue

• Depression, anxiety and mood swings

• Difficulty in losing weight

• Eating disorders

• Menstrual problems

• Fertility problems, miscarriage and premature births

• Perimenopausal and menopausal problems

• Changes in libido

• Heart disease

• Osteoporosis

• Ageing.

There is much controversy surrounding the issue of mild thyroid disease – or should it be called early or pre-thyroid disease? Despite being more widely recognized, there is little consensus on its significance and whether or how it should be treated. No one truly knows how important it is as a cause of ill health or how often it might lead to full-blown thyroid disease. Other questions remain, too: Should it be tested for in the absence of symptoms? Should women with symptoms suggestive of thyroid problems, such as tiredness and depression, be treated even if blood tests are apparently normal? Should widespread thyroid screening be introduced and, if so, at what age and how often should testing be performed?

Just as in 1995, there is a lot of debate, but no definitive answers.

Why Me?

Almost every woman included in this book wanted to know why she, in particular, had developed a thyroid disease. Unfortunately, there are no simple answers to this question. Despite its prevalence, the experts themselves still do not fully understand what causes the thyroid to misbehave. As with so many illnesses, one of the most pressing questions is whether nature or nurture lies at the root of the problem.

The cracking of the human genome, the inherited ‘database’ of some 40,000 to 50,000 genes containing all of the instructions for life, has led to an explosion of genetic research – and some interesting insights into the origin of certain kinds of thyroid problems. Some of the genes involved in certain kinds of thyroid cancer have been identified as well as other possible ‘candidate’ genes that may lead to an increased risk of developing an autoimmune thyroid disease.

However, although genes undoubtedly play a role, they are not the whole story. As with any illness with a genetic component, possessing one or more of these predisposing genes may give you a tendency to develop a particular problem – in this case, thyroid disease – but it is your environment and individual lifestyle that may yet determine whether you actually will.

The Immune Connection

The role played by the immune system in triggering a number of thyroid disorders remains a controversial topic. Autoimmune thyroid disease, which underlies both hypo- and hyperthyroidism, is caused by failure of a fundamental mechanism: the body’s ability to recognize its own organs and tissues as belonging to itself.

If the body fails to recognize itself, it produces self-attacking proteins – known as autoantibodies – to destroy its own tissue. Experts are becoming increasingly aware of a number of diverse thyroid problems due to the production of such autoantibodies, including:

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which causes an underactive thyroid

• Graves’ disease, which causes an overactive thyroid

• Myxoedema, or generalized swelling of the skin and other tissue

• Subclinical hypo-/hyperthyroidism, mild or hidden thyroid under-/overactivity

• Thyroiditis, or inflammation of the thyroid

• Postpartum thyroiditis, or inflammation of the thyroid after childbirth

• Thyroid eye disease (TED).

Putting the Clues Together

Women, as we already know, are much more likely than men to develop thyroid disease. Many of those interviewed for this book added, almost as an afterthought, ‘My mother (or sister, or daughter) has thyroid problems, too.’ In particular, Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis seem to cluster in families. In the past, this was dismissed as a coincidence. Recently, however, the new science of molecular genetics has led a number of researchers to look for an underlying inheritance factor in the development of autoimmunity. It is now generally agreed that as much as 10–15 per cent of us inherit an immune system with the potential to turn against itself.

Nevertheless, the development of thyroid problems is not just a matter of inheriting a faulty set of genes. Many people possess autoantibodies and do not go on to develop full-blown thyroid disease. In fact, it is estimated that only about one in 10 of those with an inherited tendency to develop thyroid antibodies will actually have thyroid problems.

One of the main aims of research, therefore, is to discover the possible triggers of thyroid problems. We know that the immune system can be damaged by many aspects of the 21st-century lifestyle that seem to have potential roles in the development of thyroid disease. Pollution, ageing, diet, stress, viral and bacterial infections, and habits like smoking and drinking are just some of the factors being explored by scientists in the hopes of finding out why the thyroid becomes faulty. Since 1995, much more information has been accrued on the roles these factors may play in triggering thyroid disease – and one important risk factor could simply lie in being female.

The Hormone Connection

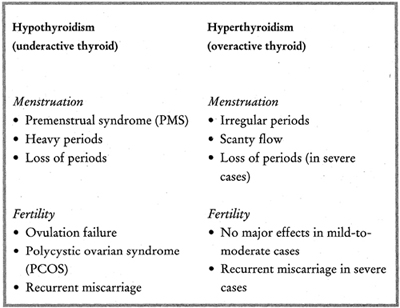

The thyroid gland is involved in virtually every bodily process, including those of the reproductive system, and thyroid disease is linked to a number of specifically female problems (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Links between thyroid disorders and the reproductive system

The first clue that something may be wrong with the thyroid gland is often when a woman consults the doctor on a ‘woman’s problem’, such as menstrual irregularities, difficulty in getting pregnant, miscarriage, postnatal depression or menopausal symptoms. It is also increasingly recognized that thyroid problems may be confused with or aggravate the symptoms of women’s problems such as PMS and the menopause.

With so many women’s problems being linked to thyroid disease and, conversely, so many thyroid problems being associated with the reproductive cycle, could it be that the female hormones play a part in susceptibility to thyroid disease? The answer is most likely yes. Research suggests that the two main female sex hormones, oestrogen and progesterone, moderate the activity of the immune system – hence the preponderance of thyroid disease in women.

The involvement of hormones and the immune system could also explain why the thyroid may misbehave for the first time during pregnancy and after birth. It also provides a reason for why so many women develop debilitating postpartum thyroiditis (PPT), which is often confused with postnatal depression.

One of the most striking developments since the first edition of this book has been the increasing awareness that the brain and nervous system, the immune system and endocrine (hormonal) system, all previously thought to be completely separate systems, do not work in isolation. This has led to the development of new fields of study such as psychoneuroendocrinology and psychoneuroimmunology, which are dedicated to exploring the body-mind connection and the way in which each ‘talks’ to the other.

With Women in Mind

This book is an exploration of these and other issues. Chapter 2 looks in detail at the thyroid gland and how it works to enable readers to understand the links between the thyroid and other body systems, and why – when it goes wrong – there may be such wide-ranging effects. The chapter also outlines some of the latest thinking on the immune system and the part it plays in thyroid problems.

Chapter 3 examines all the things that can go wrong with your thyroid, and explores some of the latest theories for how thyroid problems arise in an attempt to answer that nagging question, ‘Why me?’ There is also more detailed information on thyroid nodules (lumps) and thyroid cancer. Despite being one of the simplest forms of cancer to treat, survival rates in the UK have, until now, lagged woefully behind those of other countries.

Chapter 4 tackles the problem of getting a proper diagnosis. It includes a description of the various tests that may be performed, and explores the issue of what is normal and the difficulties involved in interpreting thyroid function tests.

Chapter 5 describes the available treatments, including medications, surgery and radiotherapy, and explains how they work, including their pros and cons. It also covers the debate over newer – and the revival of older – forms of treatment, and how you can work with your doctor to find the treatment that is right for you.

Chapter 6 covers the different ways you can help yourself, such as by paying attention to what you eat, making sure you get the right amount of exercise and managing stress, as well as how to come to terms psychologically with having thyroid disease.

Chapter 7 looks at how complementary therapies can help you manage your thyroid problems. These therapies are much more widely accepted now than when the first edition of this book was written, and many doctors and healthcare practitioners now acknowledge the part these therapies can play alongside conventional medical treatment.

Chapter 8 is devoted to thyroid eye disease, a particularly devastating condition about which too little is known, even now, and includes the still controversial issue of how it should be treated.

Chapter 9 describes how thyroid problems can affect you at different points in the female reproductive cycle, and includes important new information on how thyroid problems can affect menstruation, fertility, pregnancy and life after childbirth.

Chapter 10 looks at the problems that may be caused by thyroid disease at around the menopause and as we get older.

Chapter 11 investigates some of the major issues in thyroid disease and the advances made in our current understanding of the disorder, as well as takes a peek into the future at possible new treatments.

Finally, there is a glossary of terms relevant to thyroid disorders, and a list of books, websites and organizations that may prove helpful.