полная версия

полная версияA History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume II (of 2)

889

Wafer’s Voyage. Anderson’s Iceland. The author says that the beards are cut into slips; but these slips were fish-bone, which could be made into baskets but not into nets. He certainly meant the hair on the beard, which in Holland is used for wigs.

890

De Vest. Sac. Hebr. p. 100.

891

Hist. Nat. lib. xxxvii. cap. 3.

892

Rete, id est ornamentum sericum ad instar retis contextum. – Acta S. Deodati, tom. iii. Junii, p. 871.

893

In the Limpurg Chronicle, which may be found in Von Hontheim, Hist. Trevirensis, vol. ii. p. 1084, is the following passage: “The ladies wore new weite hauptfinstern, so that the men almost saw their breasts;” and Moser, who quotes this passage in his Phantasien, conjectures that the hauptfinstern might approach near to lace. I never met with the word anywhere else; but Frisch, in his Dictionary, says, “Vinster in a Vocabularium of the year 1492 is explained by the words drat, schudrat, thread, coarse thread.” May it not be the word fenster, a window? And in that case may it not allude to the wide meshes? Fenestratum meant formerly, perforated or reticulated; and this signification seems applicable to those shoes mentioned by Du Cange under the name of calcei fenestrati. At any rate it is certain that the article denoted by hauptfinstern belonged to those dresses mentioned by Seneca in his treatise De Beneficiis, 59. Pliny says that such dresses were worn, “ut in publico matrona transluceat.”

894

Dict. de Commerce. Copenh. 1759, fol. i. pp. 388, 576.

895

Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. liii. 1783, p. 38. In the Heiligen Lexicon St. Fiacre is improperly called the son of an Irishman of distinction.

896

Howell, in speaking of the trade in the oldest times, says, p. 222, “Silk is now grown nigh as common as wool, and become the cloathing of those in the kitchin as well as the court; we wear it not onely on our backs, but of late years on our legs and feet, and tread on that which formerly was of the same value with gold itself. Yet that magnificent and expensive prince, Henry VIII., wore ordinarly cloth-hose, except there came from Spain, by great chance, a pair of silk stockins. K. Edward, his son, was presented with a pair of long Spanish silk stockins by Thomas Gresham, his merchant, and the present was taken much notice of. Queen Elizabeth in the third year of her reign was presented by Mrs. Montague, her silk-woman, with a pair of black knit silk stockins, and thenceforth she never wore cloth any more.”

897

The lines which allude to this subject are in the tragedy of Ella: —

“She sayde, as herr whytte hondes whyte hosen were knyttinge,

Whatte pleasure ytt ys to be married!”

898

In his Description of Scotland, according to the old translation, in Hollingshed, “Their hosen were shapen also of linnen or woolen, which never came higher than their knees; their breeches were for the most part of hempe.”

899

“The king and some of the gentlemen had the upper parts of their hosen, which was of blue and crimson, powdered with castels and sheafes of arrows of fine ducket gold, and the nether parts of scarlet, powdered with timbrels of fine,” &c… There is reason however to suppose that the upper and nether parts of the hose were separate pieces, as they were of different colours. This description stands in the third volume of Hollingshed’s Chronicles, p. 807, where it is said, speaking of another festival, “The garments of six of them were of strange fashion, with also strange cuts, everie cut knit with points of fine gold, and tassels of the same, their hosen cut in and tied likewise.” What the word knit here signifies might perhaps be discovered if we had an English Journal of Luxury and Fashions for the sixteenth century.

900

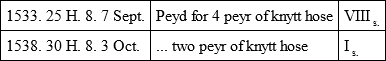

Gentleman’s Magazine, 1782, vol. lii. p. 229. From an authentic and curious household book kept during the life of Sir Tho. L’Estrange, Knt. of Hunstanton in Norfolk, by his lady Ann, daughter of the lord Vaux, are the following entries: —

It is to be observed, that the first-mentioned were for Sir Thomas and the latter for his children.

901

The act made on this occasion is not to be found in any of the old or new editions of the Statutes at Large. It is omitted in that published at London, 1735, fol. ii. p. 63, because it was afterwards annulled. Smith, in Memoirs of Wool, Lond. 1747, 8vo, i. p. 89, says it was never printed; but it is to be found in a collection of the acts of king Edward VI., printed by Richard Grafton, 1552, fol. The following passage from this collection, which is so scarce even in England that it is not named in Ames’s Typographical Antiquities, is given in the Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. liii. part 1, p. 127: – “In this acte limitinge the tymes for buieing and sellyng of wolles, mention is made of chamblettes, wolstende, saies, stamine, knitte hose, knitte peticotes, knitte gloves, knitte slieves, hattes, coives, cappes, arrasse, tapissery, coverlettes, girdles, or any other thing used to be made of woolle.”

902

This account is to be found in Hollingshed’s Chronicles. “Dr. Sands at his going to bed in Hurleston’s house, had a paire of hose newlie made, that were too long for him. For while he was in the Tower, a tailor was admitted to make him a pair of hose. One came in to him whose name was Beniamin, dwelling in Birchin-lane; he might not speak to him or come to him to take measure of him, but onelie to look upon his leg; he made the hose, and they were two inches too long. These hose he praied the good wife of the house to send to some tailor to cut two inches shorter. The wife required the boy of the house to carrie them to the next tailor, which was Beniamin that made them. The boy required him to cut the hose. He said I am not the maister’s tailor. Saith the boy, because ye are our next neighbour, and my maister’s tailor dwelleth far off, j come to you. Beniamin took the hose and looked upon them, he took his handle work in hand, and said, these are not thy maister’s hose, but Dr. Sands, them j made in the Tower.”

903

“Item, his best coat, jerkin, doublet and breeches. Item, his hose or nether stockings, shoes and garters.” – Survey of the Cathedral of St. Asaph, by Browne Willis, 1720, 8vo.

904

Hollingshed’s Chronicle, 1577, p. 213.

905

In his satyre called The Steel of Glass: – “In silk knitt hose, and Spanish leather shoes.”

906

In Hollingshed, third part, p. 1290: – “Upon the stage there stood at the one end eight small women children, spinning worsted yarne, and at the other as manie knitting of worsted yarn hose.”

907

Buch des Alten Pommerlandes, 1639, 4to, p. 388: – “Duke Bogislaus VIII. suffered himself at length to be overcome by love, and married Sophia, daughter of Procopius margrave of Moravia, who was a very prudent and moderate lady. In her old age, when her sight became bad, so that she was incapable of sewing or embroidering, she never put the knitting-needle out of her hands, as is written in our chronicles. The rhymes which she always had in her mouth are remarkable: —

Nicht beten, gern spatzieren gehn,Oft im Fenster und vorm Spiegel stehn,Viel geredet, und wenig gethan,Mein Kind, da ist nichts Fettes an.‘Never to pray; to be fond of walking; to stand often at the window and before the looking-glass; to talk much and do little; is not, my child, the way to be rich.’”

908

Mezeray, where he speaks of the silk manufactories under Henry IV.

909

The first description of the stocking-loom illustrated by figures, with which I am acquainted, is in Deering’s Nottingham, 1751, 4to, but it is very imperfect. A much better is to be found in the second volume of the Encyclopédie, printed at Paris, 1751, fol. p. 94–113. The figures are in the first volume of the second part of the Planches, and make eleven plates, eight of which are full sheets. [The reader will also find a very good description of the stocking-loom illustrated with woodcuts in Ure’s Dictionary, art. Hosiery.]

910

The following passage occurs in the petition, p. 302: “Which trade is properly stiled framework-knitting, because it is direct and absolute knit-work in the stitches thereof, nothing different therein from the common way of knitting (not much more antiently for publick use practised in this nation than this), but only in the numbers of needles, at an instant working in this, more than in the other by an hundred for one, set in an engine or frame composed of above 2000 pieces of smith, joiners, and turners work, after so artificial and exact a manner, that, by the judgement of all beholders, it far excels in the ingenuity, curiosity, and subtility of the invention and contexture, all other frames or instruments of manufacture in use in any known part of the world.”

911

This account is given by Aaron Hill in his Rise and Progress of the Beech-oil Invention, 1715, 8vo.

912

The inscription may be found in Seymour’s Survey of London, 1733, fol. vol. i. p. 603: “In the year 1589 the ingenious William Lee, Master of Arts of St. John’s College, Cambridge, devised this profitable art for stockings (but being despised went to France) yet of iron to himself, but to us and others of gold; in memory of whom this is here painted.”

913

In his History of the World, already quoted, p. 171: “Nine and thirty years after was invented the weaving of silk stockings, westcoats, and divers other things, by engines, or steel looms, by William Lee, Master of Arts of St. John’s College in Cambridge, a native of Nottingham, who taught the art in England and France, as his servants in Spain, Venice, and Ireland; and his device so well took, that now in London his artificers are become a company, having an hall and a master, like as other societies.”

914

Of this Aston the following account is to be found in Thoroton’s Nottinghamshire, 1677, fol. p. 297: “At Calverton was born William Lee, Master of Arts in Cambridge, and heir to a pretty freehold here; who seeing a woman knit, invented a loom to knit, in which he or his brother James performed and exercised before Queen Elizabeth, and leaving it to … Aston his apprentice, went beyond the seas, and was thereby esteemed the author of that ingenious engine, wherewith they now weave silk and other stockings. This … Aston added something to his master’s invention; he was some time a miller at Thoroton, nigh which place he was born.”

915

Dell’ Agricoltura, dell’ Arti, e del Commercio. Ven. 1763, 8vo.

916

Le Siècle de Louis XIV.

917

One of these, in particular, is J. F. Tresenreuter, in A Dissertation on Hops, which was printed at Nuremberg, 1759, 4to, with a preface by J. Heumann.

918

Σμίλαξ τραχεῖα.

919

Dioscor., iv. 244.

920

Hist. Plant. iii. 18.

921

xxi. 15, sect. 50.

922

Cato De Re Rustica, xxxvii. p. 55.

923

Most of the passages in ancient authors which relate to beer have been collected by Dithmar in his edition of Tacitus De Moribus German. cap. xxiii.; and by Meibom De Cerevisiis Veterum in Gronovii Thes. Antiq. Græc., ix. p. 548.

924

[The word humulus is derived from humus, fresh earth, the hop only growing in rich soils. – Loudon and Sir W. Hooker.]

925

This valuable monument of antiquity is to be found in (Nyerup) Symbolæ ad Literaturam Teutonicam, sumtibus A. F. Suhm, Havniæ 1787, 4to, pp. 331, 404.

926

Lib. xviii. cap. 7.

927

Histor. Stirpium, ii. p. 290.

928

Biblioth. Botan. i. p. 161.

929

Originum lib. xx. 3, p. 487.

930

Speculum Naturale, lib. xi. 109.

931

Lib. v. cap. 7.

932

Joh. Mesuæ Opera. Venetiis, 1589, fol.

933

Du Cange Doublet Hist. Sandionys. i. 3, p. 669.

934

In C. Meichelbeck’s Histor. Frising. I. Instrument. p. 359.

935

See the works quoted by Tresenreuter, p. 15: Pezii Thesaur. Anecdot. i. P. 3, pp. 68, 72. – J. C. Harenberg Histor. Gandersheim. p. 1350. – Eccard Origin. Saxon. p. 59. – Leukfeld Antiquit. Poeldens. p. 78.

936

F. G. de Sommersberg Silesiac. Rer. Scriptor. i. pp. 801, 829, 857. – Von Ludwig Reliq. Histor. v. p. 425. – Tresenreuter, p. 20, quotes later information in the fourteenth century.

937

L. ii. art. 52.

938

Art. 126.

939

For an account of the author and his works, which are now scarce, see Haller’s Bibliotheca Botan. i. p. 222.

940

Article Ydromel.

941

This celebrated work, known as the Schola Salernitatis, was first printed in 1649, and has since been frequently republished and translated into various languages. A very complete edition, with an English version and a history of the book, was given by the late Sir Herbert Croft. The history of this book may also be found in Giannone’s History of Naples.

942

[Loudon observes in his Encycl. Plants, that lupulus is a contraction of Lupus salictarius, the name by which it was, according to Pliny, formerly called, because it grew among the willows, to which, by twining round and choking up, it proved as destructive as the wolf to the flock.]

943

Columella, x. 116. The root (radish?) was sliced and put into the Egyptian beer along with steeped lupines, in order to render it more palatable. Lorsbach über eine Stelle des Ebn Chalican. Marburg, 1789, 8vo, p. 21.

944

Plin. xviii. 14, sect. 36. – Geopon. ii. 39, p. 189, and the passages quoted there by Niclas: Galen. de Fac. Simpl. Med. vi. 144: and Alim. Fac. i. 30.

945

De Re Rustica, i. 13, 3.

946

This document is in Matthæi Analecta Vet. Ævi, iii. p. 260. See also Du Cange, under the word Grutt, and its derivatives.

947

St. Hildegard in Physicæ, lib. ii. cap. 74. Petro Crescentio d’Agricoltura, lib. vi. cap. 56. This writer lived in the thirteenth century.

948

A celebrated female saint of the eighth century, said to have been a native of England, but canonised in Germany, where she was abbess of a nunnery at Heidensheim in Thuringia. – Trans.

949

This is asserted in the Götting. Gel. Anzeigen, 1778, p. 323.

950

Statutes at Large, vol. i. p. 591.

951

Husbandry and Trade Improved, by J. Houghton. Lond. 1727, 8vo. ii. p. 457. – Anderson’s Hist. of Commerce. [The fermented liquor anciently in use in this country is usually termed ale, but we have in fact no certain account of its composition, and all that is now known respecting it is, that it was a pleasant but intoxicating liquor. Our Saxon ancestors were so far addicted to its use, that so far back as the time of king Edgar, it was found necessary to order marks to be made in their cups at a certain height, beyond which they were forbidden to fill, under a severe penalty. This probably gave rise to the peg tankard, of which there are a few still remaining. It held two quarts, and had on the inside a row of eight pegs, one above the other, from top to bottom, so that the space between each contained half a pint. The law of compotation was, that every one who drank was to empty the exact space between peg and peg, and if he either exceeded or fell short of his measure, he was bound to drink down to the next. In archbishop Anselm’s canons, made in the council of London, A.D. 1102, we find an order, by which priests were enjoined not to go to drinking bouts, nor to drink to pegs.]

952

Archæologia, vol. iii. p. 157. [Indeed, at a much later period, the common council of the city of London petitioned parliament against the use of hops, “in regard that they would spoyl the taste of drinks and endanger the people.” – See Walter Blithe in his Improver Improved, published in 1649.]

953

Hamburgisches Magazin, xxxiii. p. 465.

954

Instead of this plant, which grows wild in Sweden, another wild plant in Germany called post, and by botanists Ledum palustre, was in old times used for beer by poor people in its stead; but it occasioned violent headaches. – See Linnæi Amœnitat. Acad. viii. p. 270. [This plant is still extensively used in the northern parts of Germany for imparting a bitter flavour to beer, although, owing to its deleterious nature, it is strictly forbidden by the laws. In this country Cocculus indicus is sometimes employed for a like purpose.]

955

This law is said to have been made as early as the reign of Magnus Smeek; but it was confirmed by king Christopher in 1440, and by the command of Charles IX. was printed at Stockholm, in folio, in 1608, in a work entitled Swerikes Rijkes Landz-lagh. The passage which belongs to this subject stands in Bygninga Balker, cap. 49 and 50, p. xl. a.

956

Linnæi Amœnitat. Academ. vii. p. 452.

957

Gmelin’s Reise durch Sibirien. Gött. 1752, 8vo, iii. p. 55.

958

Plin. lib. xxxiii. 3, sect. 19.

959

A plate of this kind was called παράγραφος, also τροχαλὸς, γυρὸς, κυκλοτερὴς, which last appellation denotes the form. The Romans, at least those of later times, named this lead præductal. The ruler by which the lines were drawn was called κανὼν and κανονίς. Thus the ruled sheet which Suffenus filled with wretched verses is styled by Catullus membrana directa plumbo. Pollux has παραγράφειν τῇ παραγραφίδι. See Salmasius ad Solinum, p. 644, where some passages, in which these leaden plates are described, are quoted from the Anthologia.

960

Versuchs e. System d. Diplomatik. Hamb. 1802, 8vo, ii. p. 108.

961

Diplomatique-pratique: à Metz, 1765, 4to, p. 62.

962

De Metallicis, lib. iii. Rome, 1596, or Norib. 1602.

963

This, however, is not exactly the case. With ink somewhat thick one may indeed write on a piece of paper which has been rubbed over with black lead.

964

[This was formerly the case, but for a considerable number of years past the mine has been constantly open. The whole of the produce is sent up to London (Essex Street, Strand), where it is disposed of by public auction, held once a month.]

965

In the Cumberland dialect, killow or collow, as well as wad, means black. Therefore when the manganese earth, which is found chiefly at Elton not far from Winster, and when burnt is employed as an oil-colour, but particularly for daubing over ships, is called black wad, that expression signifies as much as black black. See Pennant’s Tour in Scotland, i. p. 42. Gentleman’s Magazine, 1747, p. 583.

966

Pinax Rerum Natural. London, 1667, 8vo, p. 218.

967

Natural Hist. of Westm. and Cumberland, 1709, 8vo, p. 74. See also Gent.’s Mag. xxi. 1751, p. 51, where there is a map of this remarkable district.

968

Borghini, il Riposo. Artists used sometimes also silver pencils. Baldinucci’s Vocab. dell’ arte del Disegno: Stile.

969

These sonnets are the 57th and 58th. Of Simon and his drawings an account may be found in Fiorillo Gesch. der zeichnenden Künste, Gött. 1798, 8vo, i. p. 269.

970

De’ veri precetti della pittura. Ravenna, 1587, 4to, p. 53.

971

In his observations on Vasari, iii. p. 310.

972

It is indeed a matter of indifference whether the name be derived from αμμος, arena, or rather from Ammonia, the name of a district in Libya, where the oracle of Jupiter Ammon was situated. The district had its name from sand. An H also may be prefixed to the word. See Vossii Etymol. p. 24. But sal-armoniacus, armeniacus, sal-armoniac, is improper.

973

De Re Rust. vi. 17, 7.

974

Lib. xxxi. cap. 7, sect. 39.

975

Lib. v. cap. 126.

976

This name was first used by Js. Holland.

977

Synesii Opera, ep. 147.

978

Athen. lib. ii. cap. 29, p. 67.

979

I am fully of opinion that a town named in the new maps Kesem, and which lies in Arabia Felix, opposite to the island of Socotora, is here meant. It has a good harbour. See Büsching’s Geography, where the name Korasem also occurs.

980

Geopon. lib. vi. cap. 6.

981

Pallad. i. tit. 41.

982

Bibliothek d. Naturwiss. u. Chemie. Leip. 1775, 8vo, i. p. 219.

983

Lib. xxxi. cap. 7, sect. 42.

984

[The double chloride of ammonium and iron].

985

Liber de holosantho in C. Gesner’s treatise De omni Rerum Fossilium Genere. Tiguri 1565, 8vo, p. 15.

986

What a noble people were the Arabs! we are indebted to them for much knowledge and for many inventions of great utility; and we should have still more to thank them for were we fully aware of the benefits we have derived from them. What a pity that their works should be suffered to moulder into dust, without being made available! What a shame that those acquainted with this rich language should meet with so little encouragement! The few old translations which exist have been made by persons who were not sufficiently acquainted either with languages or the sciences. On that account they are for the most part unintelligible, uncertain, in many places corrupted, and besides exceedingly scarce. Even when obtained, the possessors are pretty much in the same state as those who make their way with great trouble to a treasure, which after all they are only permitted to see at a distance, through a narrow grate. Had I still twenty years to live, and could hope for an abundant supply of Arabic works, I would learn Arabic. But ὁ βίος βραχὺς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή.

987