полная версия

полная версияBrittany

Sabine Baring-Gould

Brittany

PREFACE

Brittany can hardly claim the attention of the tourist as a superlatively beautiful country. The way in which trees are clipped and tortured out of shape disfigures the sylvan landscape; and of mountain scenery there is none. The ranges of the Montaignes Noires and the Monts d'Arrez are insignificant. Yet the valleys are pretty, but never grand. The charm of Brittany is to be found in the people and in the churches. The former with their peculiar costumes, and their customs are full of interest, and the latter are of remarkable beauty and quaintness. The ordinary tourist will hardly see much of the costume unless he attends a pardon, the Patron of the Irish peasant; the patronal feast at some chapel frequented only on the day of the pardon. But the student of men and manners will find much to interest him at such a gathering. The churches are of extraordinary beauty, they are for the most part of granite, but of a fine-grained granite that lends itself to elaborate carving. And the kersanten stone is employed, a dark volcanic product that is undercut and preserves its sharpness through centuries, and is employed for carving of lace-like delicacy. The coast scenery is fine, but not of the finest description, and varies very greatly from the granite cliffs of Finistère to the sandy dunes of the Morbihan. The towns are not comparable to those of Normandy for the number and richness of their mediæval domestic buildings, but are set in far more charming surroundings. The cathedrals are, for the most part small, Quimper and S. Pol de Léon and Tréguier have the finest, but these are of a French type, whereas the village churches possess a stamp peculiar to Brittany, where spared. Unhappily a passion has possessed the people of late to pull down their ancient churches and build new Houses of God in very questionable taste. In the diocese of Vannes the modern architecture is execrable, but the architects of Quimper are of a vastly higher type. They follow the old lines, and imitate what is good, whereas in the Côtes du Nord and in Morbihan, the modern work is insufferably vulgar and bad. The whole country teems with prehistoric antiquities, but these will only interest those who have made such monuments a special study; nevertheless Carnac and Locmariaquer and Gavr' Inis cannot fail to impress the ordinary traveller with a sense of astonishment at the majesty of the rude architecture of a lost and mysterious people of whom almost nothing is known, and whose one religious idea seems to have been, the cult of the dead.

The people are intensely religious. Religion is their passion; and the efforts made by the Republican government to tread it down, and to de-Bretonise the people, have only intensified their religious and national enthusiasm. The Breton peasant is said to have a hard head. He is obstinate and resists outside pressure to alter his creed or his customs. The old Royalist tendency of the Breton is a thing of the past. He is content to be under a republic, if the republic will only leave him alone. Fishing and shooting may be obtained on easy terms, and both are good. The roads are excellent for the cyclist, and the costumes and the architecture present inexhaustible subjects for the camera. The inns are always clean, the charges are moderate, and the fare very passable. No part of Europe is so accessible, and contains so much of interest in varied directions as Brittany. It is a delightful land for a brief visit, it is full of matter for study by one who can make there a prolonged stay. The climate is mild, and not so rainy as the West of England and Wales. The kindly people will always treat a traveller with gracious courtesy. But Brittany, it must be remembered, is divided into two very distinct portions, that in which only French is spoken, and that in which the language is Breton, closely akin to Welsh. And of Brittany, by far the most interesting portion is Finistère, where old costumes and old customs are clung to more tenaciously than elsewhere.

S. B. G.

I. General Features and Geology

Brittany, the extreme Western promontory of the North of France, comprises the five departments of Côtes-du-Nord, Ille-et-Vilaine, Finistère, Morbihan, and Loire-Inférieure. It is distinguished into Upper and Lower Brittany. In the former the French language is spoken, in the latter the Breton, and French is an acquired tongue.

The back-bone of Upper Brittany is the chain of the Menez that runs from East to West, and then branches, forming on the North the Montagnes d'Arrée, and on the South, the Montagnes Noires. The system may be likened to a hay-fork or a pair of tongs, where the prongs of the fork form the above-named ranges. The whole rests on an elevated plateau that slopes to the sea North and West, and on the South dies down into the plain of the Vilaine and the Loire.

On the North this plateau is seamed by the rivers that have cut narrow valleys and ravines through which they make their way to the sea. Such are the Rance, the Gouet, the rivière de Morlaix, with the result that there is no coast-road, and the traveller passes along the main arteries of traffic at some distance from the sea, catching a glimpse of it only once at the Anse d'Iffinac, and has to branch off from it to the coast so as to make acquaintance with the bold and picturesque coast.

The mountain range is nowhere high, and rarely reaches a thousand feet. The highest point is the Mont Saint Michel which attains to slightly over 1200 ft. The freshman arriving at Cambridge asked where was the Gogmagog range, and was told that he might see it when an intervening cart got out of the way. Owing to the ridges rising out of an elevated plateau, they are almost as insignificant as the Gogmagogs. However, the Menez-hom most nearly attains to the dignity of a mountain, as it stands above the Bay of Douarnenez, reaches however only to 990 ft.

Along the Western confines of the department of Ille-et-Vilaine, the Menez spreads out into high tableland sown with lakelets acting as feeders to the Vilaine.

The Monts d'Arrée, starting from the Coat-an-Noz in Côtes-du-Nord, extend to the peninsula of Crozon, they attain their highest point at the Mont S. Michel, and decline as they approach the sea. They rarely rise 300 ft. above the tableland on which they are planted, and this prevents them from having an imposing appearance.

The Montagnes Noires flank the central plain on the South. Their maximum height is 1050 ft. After running S.W., they bend abruptly towards the N.W., and terminate in the Menez-hom in the Crozon peninsula.

In the Morbihan, the Lande de Lanvaux, running from W. to N.E., extends 50 kilometres, and rises to the height of from 240 to 320 ft. between the basins of the Claye and the Arz which unite at Redon to feed the Vilaine.

The North coast of Brittany is eaten into bays from which the sea retreats to considerable distances, and is fringed with reefs and islands. It is a favourite resort of Parisians, throughout its stretch, from Dinard to Plestin.

The West of this peninsula is torn into shreds of promontories with deep inlets between them. The promontories of S. Mathieu, Crozon, Sizun, and Penmarch are bald, but bold. Below the point of Penmarch the coast rapidly trends S.E. and alters in character; it loses its bleak desolation and ragged rocky nature, and forms landlocked seas, as those of Belz and the Morbihan; and the rocks make way for sand-dunes. The island chain that constitutes a natural breakwater to the bay of Quiberon is the wreckage of the barrier of another inland sea, broken up by the Atlantic surges. South of the mouth of the Loire the island of Noirmoutier stretches almost sufficiently far out to enclose another.

The plateau formation of the country is not conducive to beauty, and its lovely sites must be sought in the valleys, and its wildest scenes on the coast. The deep cleft ravine of the Rance, the sweet valley of the Elorn, that of the Aulne, canalised, the Blavet, the Laïta and the Arz, will richly repay tracing upward.

The promontories of Crozon and Sizun till of late years were bare and untilled, and heath-grown; but the use of sardine heads as manure has given a great impetus to agriculture, and the demand for fir balks for the South Welsh mines has caused the planting of vast tracts with the Austrian pine.

The geological structure of Brittany is simple. It consists of an immense upheaval of granite through beds of Silurian and Cambrian schist. Rare deposits of lime occur in the folds of these beds. Dykes of quartz and diorite have traversed the schist and granite, and the face of the country is spotted with eruptions of igneous matter. It is as though the crust had been full of blowholes through which the molten diorite had rushed to the surface. The presence of quartz or diorite in the neighbourhood can always be recognised by the employment of one or the other to metal the roads.

The granite extends from the bay of Mont Saint Michel to the extreme point of Finistère and reappears in the isles beyond; it is interrupted only here and there by the sedimentary beds. The Châteaulin district, however, and the basin between the prongs of the mountain fork, are all of Cambrian and Silurian beds. But from the Pointe du Raz the granite extends almost uninterruptedly to the Rhone.

The Brittany granite is for the most part fine grained and soft, so that it lends itself easily to be carved, and has been freely employed in churches and secular buildings from the 11th century. But it is readily corroded by the weather, and this has given to denuded surfaces a smooth and rounded shape, and has taken the angles off exposed masses that form tors, and has occasioned the fall of many into utter ruin.

A band of syenite runs from near Lamballe to Cap Fréhel, where it forms magnificent cliffs. Syenite again comes to the surface at Trégastel and on the coast north of Morlaix. The Monts d'Arrée are of Cambrian schist and furnish slates here and there of good quality. Taking a section across the inner basin, the granite is quitted at Plounéour, then the ridge of Cambrian schist is reached, after crossing the culminating point of S. Michel, which is of Cambrian sandstone; when we reach S. Herbot we are on Silurian beds. Continuing our course south, the sandstone makes way for slaty schists, and to this succeeds the grauwacke of Brasparts. The Montagnes Noires belong to the Silurian system.

The Kersanton stone, so extensively employed for figure and foliage sculpture in Lower Brittany, is an amphibolite with mica freely comminuted and distributed through the substance. It is very dark in colour, and hardens with exposure. It comes from quarries to the south of the Rade de Brest.

An interesting deposit is the tertiary limestone of S. Juvat beside the Rance. It is of no great extent, but is of vast commercial importance. The bed is composed of an agglomerate of shells and bones. In places it lies under a deposit of as much as 45 ft. of sand. It is a veritable mine of wealth in a country so destitute of lime as is Brittany.

A mineralogical curiosity is the staurotides found at Baud, Scaer, and in various places about the Blavet. The peasants attach a superstitious value to them as marked with the cross, and in some they affect to recognise the nails. They are often sold on stalls at a Pardon. They are formed by trapdykes that have penetrated the schist, and fused and run together some of its constituents, which have afterwards crystallised, sometimes as parallel prisms, at others as set transversely forming the ordinary or the S. Andrew's Cross.

II. Botany

The botany of Brittany is little varied owing to the slight variation in the soil and subsoil, schist and granite. It is but in rare spots where occurs limestone that the flora is different. It may be roughly divided into the class of plants that affect the inland districts and the moors, and that which flourishes on the seaboard. The flora of a slate and granitic region, whether in Scotland, Cornwall or Brittany, is much the same. In the Guérande, where there are extensive marshes, an interesting collection may be made of aquatic plants, both those living in sweet water bogs and those that grow in brackish water.

A complete flora cannot be here attempted; a brief account must suffice, with indications as to the habitat of the rarer specimens.

As one leaves the Loire, pre-eminently the mouth of the Vilaine, it is easy to note the gradual disappearance of many plants that are common south of them. A few that abound there may still occur, but as stragglers and stunted. And this contrast becomes more striking the further north we go. The cause of the poverty of the Breton flora is the uniformity of the soil and the absence of calcareous rocks, and this deprives us of an entire series of plants that abound in Normandy although the climate there is more rigorous. A small number does exist, but only, as already intimated, where there are pockets of limestone, or else on the seaboard, where they can feed on the wreckage of shells cast up by the sea, and carried inland by the gales with the sand.

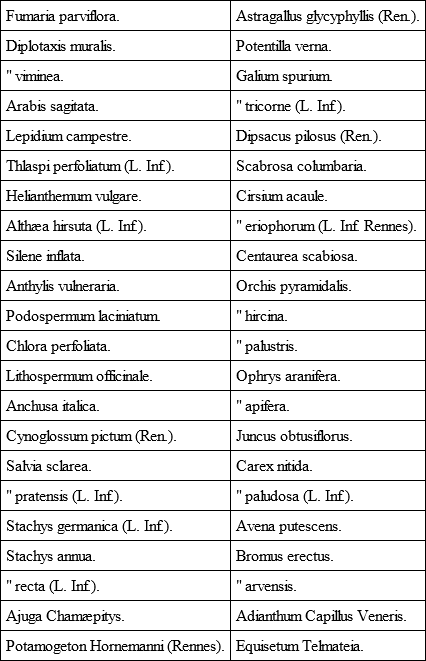

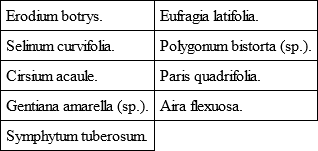

The following is a list of the plants found in calcareous soil in Brittany: —

The maritime region is more rich and interesting, and in addition to such as may be found in limestone districts already registered, the following is given as a list of plants that grow in sand: —

Brittany, as already intimated, possesses no true mountains, only elevated moorland. There are consequently to be found there no true mountainous plants. Lycopodium Selago is rare on a few elevated spots; Viola palustris and Polystichum oreopteris belong to a submountainous district. The only exceptional plant is a peculiar form of Silene maritima that grows on the summit of all the rocks of the Monts d' Arrée. This range was once doubtless covered by forest, as is shown by the presence on it of Vaccinium myrtillus, a plant that lives in the shade of trees, and which lingers on, in a stunted condition, although the sheltering boughs are long departed.

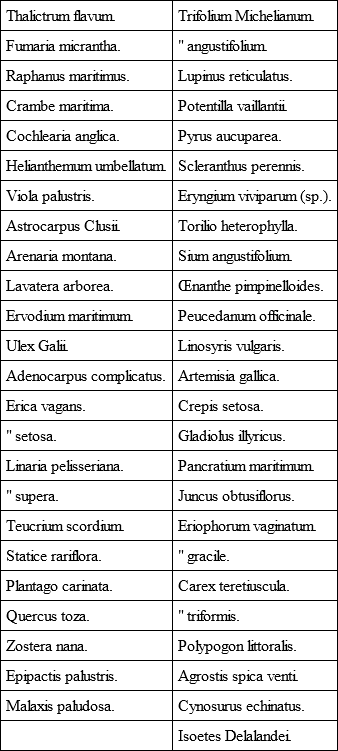

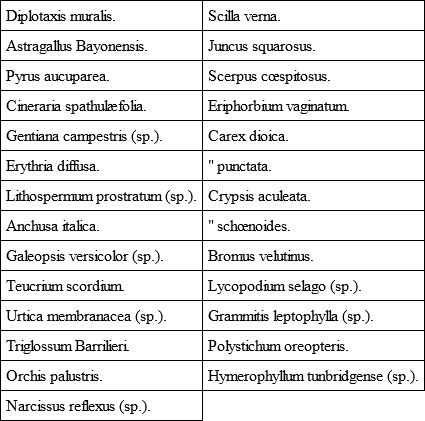

The following is a list of some of the plants of Lower Brittany that are rare in the departments of Finistère, Morbihan, and Côtes-du-Nord, omitting the names of those already given as pertaining to calcareous soils and the seaboard sands: —

These in addition have been noted in Finistère: —

These also in the Côtes-du-Nord: —

Côtes-du-Nord has the advantage of the limestone bed of S. Juvat, where many of the plants given in the first list may be gathered. Ille-et-Vilaine is still more favourably situated for calcareous rocks. There is a considerable basin south of Rennes, with a corresponding flora, generally known to botanists as the limestone tract of S. Jacques.

Such plants as are common throughout the country have not been included in the lists.

III. History

Brittany, whose ancient name was Armorica (Ar môr, by the sea), and which was known to the Britons and Irish as Llydau, was originally peopled by the race of the Dolmen-builders, a brown eyed and dark haired people, who strewed it with their monuments. To them followed the Gauls, blue eyed and with flaxen hair; these latter were divided into five tribes that occupied severally the departments of Ille-et-Vilaine (Redones), with their capital at Rennes; Côtes-du-Nord (Curiosoliti), with their headquarters at Corseul, near Dinan; Finistère (Osismi), their capital of Carhaix; Morbihan (Veneti), with their centre at Vannes; Loire Inférieure (Nanneti), with a capital at Nantes.

These tribes were subjugated by Cæsar, and the Veneti almost exterminated by him. Under the Romans, the culture and the language of the conquerors were rapidly assimilated. Christianity took root at Rennes and Nantes and Vannes, but almost nothing was done for the rural population, which probably still spoke its agglutinative tongue akin to the modern Basque. The stately bishops of these Gallo-Roman cities confined themselves to ministering to the cultured residents within their walls, and in villas scattered along the coast. The Gallo-Roman population had dwindled to an incredible extent, under the exactions of the imperial tax-gatherers, so that all the country residences fell into ruin, and the impoverished Gallo-Romans withdrew into the towns. But early – very early in the 5th century, fleets of British settlers came over, flying from the swords of Picts and Scots, and occupied the land about the mouth of the Loire. By 469 they were so numerous as to be able to send a contingent of twelve thousand men to the assistance of the Romans against the Visigoths.

As a consequence of the Saxon invasion of Britain the immigration grew, and the dispossessed islanders sought and found a new home in the Armorican peninsula, where they established themselves under their own princes, with their own institutions, civil and ecclesiastical, and their own tongue. Thenceforth Armorica ceased to be so called, and received the name of Lesser Britain, and the current language became British, identical with that now spoken in Wales, and spoken till the 17th century in Cornwall as well. Contact with France along the East has gradually thrust back the Breton language, but it is still spoken from Guingamp, in a slanting line to the mouth of the Loire. Two British kingdoms were formed, Domnonia and Cornubia; the former included the Côtes-du-Nord and Finistère above the river Elorn, and Cornubia or Cornouaille was the district below that river, the basin between the Monts d'Arrée and the Montagnes Noires, and stretched to the river Ellé at Quimperlé. All the department of Morbihan was the Bro-Weroc, a county, but the British chief did not call himself its king, probably because the colonists did not get hold of Vannes, the capital, which they enveloped but left unmolested.

At first the British colonists admitted their allegiance to their native princes in Britain, who certainly came over, and were granted certain lands as the royal dominium in the newly settled land. Thus we have Geraint, King of Devon, with his palace in Belle Ile, and portions of the newly-acquired territory on the Blavet, in Morbihan, and near Matignon, in Côtes-du-Nord. His son Solomon, or Selyf, as was his British name, also came over, and is said to have fallen at Langollen, probably whilst endeavouring to enforce taxes on the native original pagan inhabitants.

But as the insular power of the Britons was broken, the colonists considered themselves independent, and acknowledged a loose and ill-defined submission to the Frank kings at Paris, who, however, left them to be governed by their native rulers.

But not only did Britons settle in the land. Large numbers of Irish arrived from Ossory and Wexford, at the close of the 5th century, and settled along the west and north coast. No traces of them are found south of Hennebont, or west of Guingamp, but all the coastline of Cornouaille and Léon was studded thick with them.

Now only was a serious attempt made to convert the native population. The chiefs who came over were attended or followed by their brothers and cousins who were ecclesiastics, and these were granted lands on condition that they educated the young of the freeborn colonists of the tribe, and ministered in sacred matters to the tribesmen.

The work of the evangelisation of Ireland seems to have sent a thrill through Brittany, and to have been taken up there with energy. Missionary colleges were formed by some of the assistants of Patrick, which should serve as training places for those who were to assist in carrying on the apostolic work in Ireland.

The principal Irish founders in the country were: – Fiacc, Bishop of Sletty, called in Breton Vi'ho; Tighernac, Bishop of Clogher and Clones, in Breton Thégonnec; Eugenius, Bishop of Ardstraw, in Breton Saint Tugean; Senan, Abbot of Inniscathy (Breton Seny), Setna, his disciple, in Breton Sezni; Conleath, Bridget's domestic bishop, in Breton Coulitz, Ronan and Brendan.

The principal British founders were: – Cadoc, Brioc, Tugdual, Leonore, Paulus Aurelianus, Curig, Caradoc, Gildas, and his crippled son Kenneth; David, Samson, Malo, Arthmael, Meven, and Mancen or Mawgan – this latter closely allied with the Irish mission. Nonna, mother of S. David, Ninnoc, Noyala, and disciples of S. Bridget, established institutions for the education of the daughters of the freemen of the tribe to which the schools were attached.

In 845, Nominoe, who had been invested with the lieutenancy of Brittany by Louis the Pious, led a revolt against Charles the Bald, and established the independence of Brittany that lasted till the Duchess Anne brought it under the French crown, 1491. From the close of the 9th century, and throughout the 10th, the coast was ravaged by the Northmen, Frisians and Danes, and the insecurity inland caused the desertion of the country and the flight of the monks carrying the relics of their founders to walled towns in the heart of France. That Brittany should thus fall a prey to these invaders was largely due to the divisions that existed among its princes, who could not or would not combine against the common foe. At length Alan, Count of Vannes, did succeed in rallying the Britons, and defeated the Northern pirates, which secured rest for fifteen years. For the first time under him did the Gallo-Roman towndwellers consent to make common cause with the descendants of the British colonists.

On the death of Alan (907) the Northmen reappeared, and a great many Bretons under Count Matthuedoi of Poher fled to England and threw themselves on the protection of Athelstan.

In 938, Alan Barbetorte, godson of Athelstan, returned from England and drove out the Normans. Nantes was in such complete ruin that when Alan sought to reach the fallen altar of the cathedral church, there to offer up his thanks for victory gained, he was constrained to hew his way to it through a thicket of thorns and brambles.

After the expulsion of the Northmen Brittany was reorganised. Hitherto the colonists had been divided into tribes, each of which was a plou, and no Gallo-Roman could enter into one such. But after the victories of Alan Barbetorte the plous were not reconstructed, and the feudal system succeeded to that which was tribal.

Brittany was now broken up into a hierarchy of counties and seigneuries, and the king abandoned the royal title and contented himself with that of duke. The great counties were those of Léon, Cornouaille, Poher, Porhoet, Penthièvre, Rennes and Nantes. Five barons defended the eastern frontier, holding their fiefs under the Count of Rennes; these were Châteaubriant, la Guerche, Vitré, Fongères and Combourg. The whole vast inland forest was given to the Counts of Rennes, it was Porhoet. It was divided into two parts. In the east the seigneuries of Gael, Loudéac and Malestroit were created as fiefs. In the west there was but a single seigneurie, that of Porhoet; the viscount lived at Josselin. Later it was broken up and gave birth to the viscounty of Rohan.

The old kingdom of Cornouaille became a county with vassal barons at Pont l'Abbé, Pont Croix, the abbot of Landevennec, and the viscount of Le Faou. In the interior were the viscounts of Poher and Gourin.

The old kingdom of Domnonia was divided into three counties, Léon, Penthièvre and Tréguier.

The Ducal crown did not long remain in the family of Alan Barbetorte. After internecine war lasting forty years, Conan, Count of Rennes, assumed the title (990), and the dukes of his house spent their time in fighting and crushing their own kinsmen. Geoffrey I. had married a Norman wife, and he had by her two sons, Alan and Eudo. In 1034 Eudo, jealous and ambitious, demanded of his brother a share in the duchy. Alan gave him the counties of Tréguier and Penthièvre, and thus Eudo became the ancestor of that great and dangerous family of Penthièvre, which maintained undying rivalry with the ducal house, and made of Brittany a field of civil war for centuries. Conan II. succeeded as a child of three months, and his uncle ruled in his name, aided by the Normans. When Conan came of age, he had to fight against Eudo; he invaded Normandy, but was cut off by poison. When William the Conqueror became King of England, Brittany was nipped between France and Normandy, and became an object of ambition to both, and a common battlefield.