полная версия

полная версияThe Memoirs of Admiral Lord Beresford

Fighting every mile of the great river pouring down from Khartoum, we on the Cataracts had no news of Gordon. All we knew was that there was need to hurry, hurry all the way. At such times as the mail from home arrived upon a dyspeptic camel, we got scraps of news of home affairs. People who knew much more than Lord Wolseley, were saying he ought to have taken the Souakim-Berber route instead of the Nile route. I said then, as I say now, he had no choice. At this time of crisis, when the Navy was dangerously inadequate, one political party was screaming denunciations against "legislation by panic." Encouraging to sailors and soldiers sweating on service! But we knew what to expect. I observe that in a private letter written in December, 1884, from the banks of the Nile, at the end of a long day's work with the boats, I said, "Both sides are equally to blame for the defective state of the Navy. Tell – and – not to be unpatriotic and make the Navy a party question, or they will not do half the good they might."

We came to Ambigol to find the boats had been cleared by Alleyne of the Artillery. I was able to improve the organisation there, and to give help along the river I was in time to save three boats. At Dal, I laid lines along the centre of the two and a half miles rapid, so that in calm weather the boats could haul themselves through.

In the meantime, the Naval Brigade of which Lord Wolseley had ordered me to take command, had been selected, at my request, by Captain Boardman.

On 19th December, my first division came to Dal. Up they came, all together in line ahead, under all possible sail, using the boat awnings as spinnakers. They had sailed up the rapids where the other boats were tracking; and the soldiers cheered them as they went by. There was not a scratch on any boat, nor a drop of water in any of them. Every cargo was complete in detail, including machine guns, ammunition, oil and stores. Had I not a right to be proud of the seamen? I put an officer at the helm of each boat, and told them to follow me through Dal Cataract; and led them through, so that the same night the boats were reloaded with the gear and cargo which had been portaged, and were going on. The passage of Dal Cataract usually occupied three days.

I sent on the first division, and stayed at Dal to await the arrival of the second, in order to get all my men together. As it happened, I did not see it until it reached Korti. On 21st December it had left Sarras, bringing oil and stores to be used in the Nile steamers of which I was to take charge. For by this time I had been informed of Lord Wolseley's intention to send the Naval Brigade with the Camel Corps to make a dash across the Bayuda Desert to Metemmeh. The Naval Brigade was then to attack Khartoum in Gordon's steamers, while the Camel Corps attacked it by land.

So I remained yet a little while at Dal, helping the boats through the Cataract, and camping in the sand. I found a baby scorpion two and a half inches long in my handkerchief. The officer whose tent was next to mine, shared it with a sand-rat, which used to fill his slippers with dhura grains every night, and which jumped on and off my knee when I breakfasted with my friend. Actually there came two or three days when I had nothing to do; and when I could take a hot bath in peace, with the luxury of a cake of carbolic soap, and sit in my little canvas chair, which was, however, speedily stolen.

My poor servant José was suddenly taken with so sharp an attack of fever that he was stricken helpless and could hardly lift a cup to his lips. His pulse was going like a machine gun. He was too ill to be moved on mule-back to the hospital, which was eight miles distant; and I had to doctor him myself. I gave him castor-oil, deprived him of all food for twenty-four hours, gave him five grains of quinine every two hours, and plenty of lime-juice to drink; and he was soon well again.

Lord Avonmore, Lieutenant-Colonel J. Alleyne, Captain Burnaby and myself subscribed to a Christmas dinner of extraordinary charm, eaten with the Guards. The menu was: – soup made of bully beef, onions, rice and boiled biscuit, fish from the Nile, stewed bully beef and chicken à la as-if-they-had-been-trained-for-long-distance-races-for-a-year, entremet of biscuit and jam. Rum to drink.

I should have missed that feast, and should have been on the way to Korti post-haste several days before Christmas, had it not been that a telegram sent by Lord Wolseley to me had been delayed in transmission. On 27th December I received an urgent telegram from General Buller, asking where I was and what I was doing. A week previously Lord Wolseley had telegraphed instructions that I was to proceed to Korti with all speed to arrive with the first division of the Naval Brigade. Having received no orders, I was waiting for the second division so that I might see that it was complete and satisfactory. (It arrived at Dal the day after I left that place in obedience to General Buller's orders.)

From Dal to Korti, as the crow flies, is some 200 miles to the southward; following up the river, which, with many windings, flows north from Korti, the distance is more than half as much again. I was already (by no fault of mine) a week behind; my instructions were to proceed by the shortest possible route by the quickest possible means, camels or steam pinnace; and immediately I received General Buller's telegram I dashed off to the Commissariat. Here I obtained four camels to carry José, myself and my kit to the nearest point at which I could catch a steam pinnace on the river. Also, by riding the first stage of the journey, I could avoid two wide bends of the Nile. The camels were but baggage animals; they all had sore backs; and I could get no proper saddle. I strapped my rug on the wooden framework. We started the same evening at seven o'clock.

The night had fallen when we left behind us the stir of the armed camp and plunged into the deep stillness of the desert. The brilliant moonlight sharply illumined the low rocky hills, and the withered scrub, near and far; the hard gravelly track stretched plainly before us; and the camels went noiselessly forward on their great padded feet. So, hour after hour. It was one o'clock upon the following morning (21st December) when we rode into a dark and silent village. Lighting upon an empty hut, we crawled into it, cooked a little supper, and went to sleep.

Before daylight we were awakened by the noise of voices crying and quarrelling; and there were two black negresses upbraiding us, and beyond them was a group of agitated natives. It appeared that we were desecrating the village mosque. Having soothed the inhabitants, we started. That day we rode from 6 a.m. to 7.30 p.m. with a halt of an hour and a half at midday, travelling 40 miles in twelve hours, good going for baggage camels with sore backs. By that time I was getting sore, too. We slept that night at Absarat, started the next morning (29th December) at 8.30, and rode to Abu Fatmeh, arriving at 4 p.m. Starting next morning at nine o'clock, we arrived at Kaibur at 5 p.m. Here, to my intense relief, we picked up Colville and his steam pinnace, in which we instantly embarked for Korti.

During the last three days and a half we had been thirty-two hours in the saddle (which, strictly speaking, my camel had not) and a part of my anatomy was quite worn away. I lay down in the pinnace and hoped to become healed.

We did not know it; but the same evening, General Sir Herbert Stewart's Desert Column left Korti upon the great forced march of the forlorn hope.

The pinnace, whose furnaces were burning wood, most of which was wet and green, pounded slowly up river until we met the steamer Nassifara, into which I transferred myself. Blissful was the rest in that steamer after my two months' tremendous toil getting the boats through the Bab-el-Kebir and the long ride across the desert. So I lay in the steamer and lived on the height of diet, fresh meat, milk, butter and eggs, till my tunic hardly held me. I did not then know why Lord Wolseley had sent for me in so great a hurry.

CHAPTER XXVI

THE SOUDAN WAR (Continued)

IV. THE FIRST MARCH OF THE DESERT COLUMNNOTEBy the end of December, 1884, the whole of the expedition was in process of concentrating at Korti. At Korti the Nile fetches a wide arc north-eastward. The chord of the arc, running south-eastward, runs from Korti to Metemmeh, and Shendi, which stands on the farther, or east, bank. From Korti to Metemmeh is 176 miles across the desert. Shendi was the rendezvous at which the troops were to meet Gordon's steamers sent down by him from Khartoum. Wolseley's object in sending Lord Charles Beresford with the Naval Brigade was that he should take command of the steamers, which, filled with troops, were to proceed up to Khartoum. The first business of the Desert Column under General Sir Herbert Stewart, was to seize the wells of Jakdul, which lay 100 miles distant from Korti, and to hold them, thus securing the main water supply on the desert route and an intermediate station between Metemmeh and the base at Korti. Having obtained possession of the wells, the Guards' Battalion was to be left there, while the remainder of the Column returned to Korti, there to be sufficiently reinforced to return to Jakdul, and to complete the march to Metemmeh. Such was the original idea. The reason why sufficient troops and transport were not sent in the first instance, thereby avoiding the necessity of the return of the greater part of the Column to Korti, and its second march with the reinforcements, seems to have been the scarcity of camels.

When the Desert Column made its first march, Lord Charles Beresford and the Naval Brigade were still on their way to Korti. The first division under the command of Lord Charles marched with the Desert Column on its return.

The first Desert Column numbered 73 officers, 1212 men and natives, and 2091 camels. It consisted of one squadron of the 19th Hussars, Guards' Camel Regiment, Mounted Infantry, Engineers, 1357 camels carrying stores and driven by natives, Medical Staff Corps, and Bearer Company. Personal luggage was limited to 40 lb. a man. An account of the march is given by Count Gleichen, in his pleasant and interesting book (to which the present writer is much indebted) With the Camel Corps up the Nile (Chapman & Hall). Some years previously the route from Korti to Metemmeh had been surveyed by Ismail Pasha, who had intended to run a railway along it from Wady Halfa to Khartoum; and the map then made of the district was in possession of the Column. The enemy were reported to be about; but it was expected that they would be found beyond the Jakdul Wells; as indeed they were.

The Desert Column started from Korti on the afternoon of Tuesday, 30th December, 1884. The Hussars escorted a party of native guides and scouted ahead. The Column marched the whole of that night, in the light of a brilliant moon, across hard sand or gravel, amid low hills of black rock, at whose bases grew long yellow savas grass and mimosa bushes, and in places mimosa trees.

At 8.30 on the morning of the 31st December they halted until 3 p.m., marched till 8.30 p.m., found the wells of Abu Hashim nearly dry, marched on, ascending a stony tableland, and still marching, sang the New Year in at midnight; came to the wells of El Howeiyat, drank them dry and bivouacked until 6 a.m. on the morning of the 1st January, 1885.

All that morning they marched, coming at midday to a plain covered with scrub and intersected with dry water-courses; rested for three hours; marched all that night, and about 7 a.m. on the morning of 2nd January, entered the defile, floored with large loose stones and closed in with steep black hills, leading to the wells of Jakdul. These are deep pools filling clefts in the rock of the hills encompassing the little valley, three reservoirs rising one above the other. Count Gleichen, who was the first man to climb to the upper pools, thus describes the middle pool.

"Eighty feet above my head towered an overhanging precipice of black rock; behind me rose another of the same height; at the foot of the one in front lay a beautiful, large ice-green pool, deepening into black as I looked into its transparent depths. Scarlet dragon-flies flitted about in the shade; rocks covered with dark-green weed looked out of the water; the air was cool almost to coldness. It was like being dropped into a fairy grotto, at least so it seemed to me after grilling for days in the sun."

When the Desert Column reached that oasis, they had been on the march for sixty-four hours, with no more than four hours' consecutive sleep. The time as recorded by Count Gleichen was "sixty-four hours, thirty-four hours on the move and thirty broken up into short halts." The distance covered was a little under 100 miles; therefore the camels' rate of marching averaged as nearly as may be two and three-quarter miles an hour throughout. A camel walks like clock-work, and if he quickens his speed he keeps the same length of pace, almost exactly one yard.

The Guards' Battalion, to which were attached the Royal Marines, with six Hussars and 15 Engineers remained at the Wells. The rest of the Column left Jakdul at dusk of the day upon which they had arrived, to return to Korti, bivouacking that night in the desert.

The detachment at Jakdul made roads, built forts, and laid out the camp for the returning Column. On 11th January, a convoy of 1000 camels carrying stores and ammunition, under the command of Colonel Stanley Clarke, arrived at Jakdul.

In the meantime, on 31st December, the day after which the Desert Column had started for the first time, Lord Wolseley had received a written message from Gordon, "Khartoum all right," dated 14th December. Should it be captured, the message was intended to deceive the captor. The messenger delivered verbal information of a different tenure, to the effect that Gordon was hard pressed and that provisions were becoming very scarce.

At the time of the starting of the Desert Column upon its second march, when it was accompanied by the first division of the Naval Brigade under the command of Lord Charles Beresford, and by other reinforcements, the general situation was briefly as follows.

The River Column, which was intended to clear the country along the Nile, to occupy Berber, and thence to join the Desert Column at Metemmeh, was assembling at Hamdab, 52 miles above Korti. It was commanded by General Earle. The four steamers sent down the river from Khartoum by General Gordon in October, were at Nasri Island, below the Shabloka Cataract, half-way between Khartoum and Metemmeh, which are 98 miles apart. Korti and Berber, as a glance at the map will show, occupy respectively the left and right corners of the base of an inverted pyramid, of which Metemmeh is the apex, while Khartoum may be figured as at the end of a line 98 miles long depending from the apex. The Desert Column traversed one side of the triangle, from Korti to Metemmeh; the River Column was intended to traverse the other two sides.

CHAPTER XXVII

THE SOUDAN WAR (Continued)

V. THE DESERT MARCH OF THE FORLORN HOPE"When years ago I 'listed, lads, To serve our Gracious Queen,The sergeant made me understand I was a 'Royal Marine.'He said we sometimes served in ships, And sometimes on the shore;But did not say I should wear spurs, Or be in the Camel Corps." Songs of the Camel Corps (Sergt. H. EAGLE, R.M.C.C.)Korti was a city of tents arrayed amid groves of fronded palm overhanging the broad river; beyond, the illimitable coloured spaces of the desert, barred with plains of tawny grass set with mimosa, and green fields of dhura, and merging into the far rose-hued hills. All day long the strong sun smote upon its yellow avenues, and the bugles called, and the north wind, steady and cool, blew the boats up the river, and the men, ragged and cheery and tanned saddle-colour, came marching in and were absorbed into the great armed camp. Thence were to spring two long arms of fighting men, one to encircle the river, the other to reach across the desert, strike at Khartoum and save Gordon.

The day after I arrived at Korti, 5th January, 1885, the desert arm had bent back to obtain reinforcements; because there were not enough camels to furnish transport for the first march.

The first division of the Naval Brigade, under Lieutenant Alfred Pigott, also arrived on the 5th. Officers and men alike were covered with little black pustules, due to the poison carried by the flies. Nevertheless, they were fit and well and all a-taunto. They were brigaded under my command with Sir Herbert Stewart's Desert Column. The intention was that Gordon's steamers, then waiting for us somewhere between Metemmeh and Khartoum, should be manned with the sailors and a detachment of infantry, and should take Sir Charles Wilson up to Khartoum. The second division of the Naval Brigade was still on its way up. It eventually joined us at Gubat. I may here say, for the sake of clearness, that Gubat is close to Metemmeh and that Shendi lies on the farther, or east, bank of the Nile, so that Gubat, Metemmeh and Shendi were really all within the area of the rendezvous at which the River Column under General Earle was intended to join forces with the Desert Column.

Sir Herbert Stewart arrived at Korti on the 5th and left that place on the 8th, the intervening days being occupied in preparations. An essential part of my own arrangements consisted in obtaining spare boiler-plates, rivets, oakum, lubricating oil, and engineers' stores generally, as I foresaw that these would be needed for the steamers, which had already been knocking about the Nile in a hostile country for some three months. At first, Sir Redvers Buller refused to let me have either the stores or the camels upon which to carry them. He was most good-natured and sympathetic, but he did not immediately perceive the necessity.

"What do you want boiler-plates for?" he said. "Are you going to mend the camels with them?"

But he let me have what I wanted. (I did mend the camels with oakum.) With other stores, I took eight boiler-plates, and a quantity of rivets. One of those plates, and a couple of dozen of those rivets, saved the Column.

The Gardner gun of the Naval Brigade was carried in pieces on four camels. Number one carried the barrels, number two training and elevating gear and wheels, number three the trail, number four, four boxes of hoppers. The limber was abolished for the sake of handiness. The gun was unloaded, mounted, feed-plate full, and ready to march in under four minutes. When marching with the gun, the men hauled it with drag-ropes, muzzle first, the trail being lifted and carried upon a light pole. Upon going into action the trail was dropped and the gun was ready, all the confusion and delay caused by unlimbering in a crowded space being thus avoided.

At midday the 8th January, the Desert Column paraded for its second and final march, behind the village of Korti, and was inspected by Lord Wolseley. The same thought inspired every officer and man: we are getting to the real business at last.

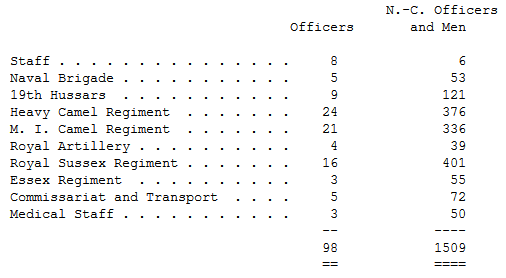

The Desert Column, quoting from the figures given in Sir Charles Wilson's excellent work, From Korti to Khartoum, was composed as follows:

N. – C. OfficersOfficers and Men

And four guns (one Gardner, three 7-pr. screw guns), 304 natives, 2228 camels, and 155 horses. Already there were along the route at the wells of Howeiyat (left on the first march) 33 officers and men of the M. I. Camel Regiment and 33 camels; and at Jakdul 422 officers and men of the Guards' Camel Regiment (including Royal Marines), Royal Engineers, and Medical Staff, and 20 camels. The Desert Column picked up these detachments as it went along, leaving others in their places.

The Column rode off at 2 o'clock p.m. amid a chorus of good wishes from our comrades. I rode my white donkey, County Waterford, which had been sent up to Korti by boat, We marched ten miles; halted at sunset and bivouacked, and started again half an hour after midnight. The moon rode high, and it was very cold; but the cold was invigorating; and the hard gravel or sand of the track made good going. Desert marching with camels demands perpetual attention; the loads slip on the camels and must be adjusted; a native driver unships the load and drops it to save himself trouble; camels stray or break loose. By means of perpetual driving, the unwieldy herd creeps forward with noiseless footsteps, at something under three miles an hour.

Although the camels were so numerous, their numbers had been reduced to the bare requirements of that small mobile column, which alone could hope to achieve the enterprise.

At 10 o'clock a.m. on the 9th, we halted for four hours in a valley of grass and mimosa trees; marched till sunset and came to another grassy valley and bivouacked. On the 10th we started before daylight, and reached the wells of El Howeiyat at noon, very thirsty, and drank muddy water and breakfasted; marched on until long after dark over rough ground, the men very thirsty, the camels slipping and falling all over the place, and at length bivouacked. Starting again before daylight on the 11th, we came to the wooded valley set among granite hills, where are the wells of Abu Halfa, men and animals suffering greatly from thirst. The wells consisted of a muddy pond and a few small pools of bitter water. More holes were dug, and the watering went on all the afternoon and all night.

Next morning, 12th January, we loaded up at daylight, and marched across the plain lying beneath the range of yellow hills, broken by black rocks, called Jebel Jelif; entered a grassy and wide valley, ending in a wall of rock; turned the corner of the wall, and came into a narrower valley, full of large round stones, and closed in at the upper end by precipices, riven into clefts, within which were the pools of Jakdul. We beheld roads cleared of stones, and the sign-boards of a camp, and the forts of the garrison, and stone walls crowning the hills, one high on the left, two high on the right hand. In ten days the little detachment of Guards, Royal Marines and Engineers under Major Dorward, R.E., had performed an incredible amount of work: road-making, wall-building, laying-out, canal-digging and reservoir-making. All was ready for Sir Herbert Stewart's force, which took up its quarters at once.

That evening the Guards gave an excellent dinner to the Staff, substituting fresh gazelle and sand-grouse for bully-beef. All night the men were drawing water from the upper pool of the wells, in which was the best water, by the light of lanterns.

The next day, 13th January, all were hard at work watering the camels and preparing for the advance on the morrow. The camels were already suffering severely: some thirty had dropped dead on the way; and owing to the impossibility of obtaining enough animals to carry the requisite grain, they were growing thin. It will be observed that the whole progress of the expedition depended upon camels as the sole means of transport.

When a camel falls from exhaustion, it rolls over upon its side, and is unable to rise. But it is not going to die unless it stretches its head back; and it has still a store of latent energy; for a beast will seldom of its own accord go on to the last. It may sound cruel; but in that expedition it was a case of a man's life or a camel's suffering. When I came across a fallen camel, I had it hove upright with a gun-pole, loaded men upon it, and so got them over another thirty or forty miles. By the exercise of care and forethought, I succeeded in bringing back from the expedition more camels, in the proportion of those in my control, than others, much to the interest of my old friend Sir Redvers Buller. He asked me how it was done; and I told him that I superintended the feeding of the camels myself. If a camel was exhausted, I treated it as I would treat a tired hunter, which, after a long day, refuses its food. I gave the exhausted camels food by handfuls, putting them upon a piece of cloth or canvas, instead of throwing the whole ration upon the ground at once.

Major Kitchener (now Lord Kitchener of Khartoum), who was dwelling in a cave in the hillside, reported that Khashm-el-Mus Bey, Malik (King) of the Shagiyeh tribe, was at Shendi with three of Gordon's steamers. (He was actually at Nasri Island.) Lieutenant E. J. Montagu-Stuart-Wortley, King's Royal Rifles, joined the column for service with Sir Charles Wilson in Khartoum. Little did we anticipate in what his plucky service would consist. Colonel Burnaby came in with a supply of grain, most of which was left at Jakdul, as the camels which had brought it were needed to carry stores for the Column. There were 80 °Commissariat camels, carrying provisions for 1500 men for a month, the first instalment of the depot it was intended to form at Metemmeh, as the base camp from which to advance upon Khartoum.