полная версия

полная версияExpositor's Bible: The Epistles of St. John

This humility may be traced incidentally in other regions of the Christian life. Thus he speaks of the possibility at least of his being among those who might "shrink with shame from Christ in His coming." He does not disdain to write as if, in hours of spiritual depression, there were tests by which he too might need to lull and "persuade his heart before God."[110]

(3) St. John again has a boundless faith in prayer. It is the key put into the child's hand by which he may let himself into the house, and come into his Father's presence when he will, at any hour of the night or day. And prayer made according to the conditions which God has laid down is never quite lost. The particular thing asked for may not indeed be given; but the substance of the request, the holier wish, the better purpose underlying its weakness and imperfection, never fails to be granted.[111]

(4) All but superficial readers must perceive that in the writings and character of St. John there is from time to time a tonic and wholesome severity. Art and modern literature have agreed to bestow upon the Apostle of love the features of a languid and inert tenderness. It is forgotten that St. John was the son of thunder; that he could once wish to bring down fire from heaven; and that the natural character is transfigured not inverted by grace. The Apostle uses great plainness of speech. For him a lie is a lie, and darkness is never courteously called light. He abhors and shudders at those heresies which rob the soul first of Christ, and then of God.[112] Those who undermine the Incarnation are for him not interesting and original speculators, but "lying prophets." He underlines his warnings against such men with his roughest and blackest pencil mark. "Whoso sayeth to him 'good speed' hath fellowship with his works, those wicked works"[113]– for such heresy is not simply one work, but a series of works. The schismatic prelate or pretender Diotrephes may "babble;" but his babblings are wicked words for all that, and are in truth the "works which he is doing."

The influence of every great Christian teacher lasts long beyond the day of his death. It is felt in a general tone and spirit, in a special appropriation of certain parts of the creed, in a peculiar method of the Christian life. This influence is very discernible in the remains of two disciples of St. John,[114] Ignatius and Polycarp. In writing to the Ephesians, Ignatius does not indeed explicitly refer to St. John's Epistle, as he does to that of St. Paul to the Ephesians. But he draws in a few bold lines a picture of the Christian life which is imbued with the very spirit of St. John. The character which the Apostle loved was quiet and real; we feel that his heart is not with "him that sayeth."[115] So Ignatius writes – "it is better to keep silence, and yet to be, than to talk and not to be. It is good to teach if 'he that sayeth doeth.' He who has gotten to himself the word of Jesus truly is able to hear the silence of Jesus also, so that he may act through that which he speaks, and be known through the things wherein he is silent. Let us therefore do all things as in His presence who dwelleth in us, that we may be His temple, and that He may be in us our God." This is the very spirit of St. John. We feel in it at once his severe common sense and his glorious mysticism.

We must add that the influence of St. John [116]may be traced in matters which are often considered alien to his simple and spiritual piety. It seems that Episcopacy was consolidated and extended under his fostering care. The language of Ignatius (probably his disciple) upon the necessity of union with the Episcopate is, after all conceivable deductions, of startling strength. A few decades could not possibly have removed Ignatius so far from the lines marked out to him by St. John as he must have advanced, if this teaching upon Church government was a new departure. And with this conception of Church government we must associate other matters also. The immediate successors of St. John, who had learned from his lips, held deep sacramental views. The Eucharist is "the bread of God, the bread of heaven, the bread of life, the flesh of Christ." Again Ignatius cries – "desire to use one Eucharist, for one is the flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup unto oneness of His blood, one altar, as one Bishop, with the Presbytery and deacons."[117] Hints are not wanting that sweetness and life in public worship derived inspiration from the same quarter. The language of Ignatius is deeply tinged with his passion for music.[118] The beautiful story, how he set down, immediately after a vision, the melody to which he had heard the angels chanting, and caused it to be used in his church at Antioch, attests the impression of enthusiasm and care for sacred song which was associated with the memory of Ignatius.[119] Nor can we be surprised at these features of Ephesian Christianity, when we remember who was the founder of those Churches. He was the writer of three books. These books come to us with a continuous living interpretation of more than seventeen centuries of historical Christianity. From the fourth Gospel in large measure has arisen the sacramental instinct, from the Apocalypse the æsthetic instinct, which has been certainly exaggerated both in the East and West. The third and sixth chapters of St. John's Gospel permeate every baptismal and eucharistic office. Given an inspired book which represents the worship of the redeemed as one of perfect majesty and beauty, men may well in the presence of noble churches and stately liturgies, adopt the words of our great English Christian poet —

"things which shed upon the outward frameOf worship glory and grace – which who shall blameThat ever look'd to heaven for final rest?"The third book in this group of writings supplies the sweet and quiet spirituality which is the foundation of every regenerate nature.

Such is the image of the soul which is presented to us by St. John himself. It is based upon a firm conviction of the nature of God, of the Divinity, the Incarnation, the Atonement of our Lord. It is spiritual. It is pure, or being purified. The highest theological truth – "God is Love" – supremely realised in the Holy Trinity, supremely manifested in the sending forth of God's only Son, becomes the law of its common social life, made visible in gentle patience, in giving and forgiving.[120] Such a life will be free from the degradation of habitual sin. Yet it is at best an imperfect representation of the one perfect life.[121] It needs unceasing purification by the blood of Jesus, the continual advocacy of One who is sinless. Such a nature, however full of charity, will not be weakly indulgent to vital error or to ambitious schism;[122] for it knows the value of truth and unity. It feels the sweetness of a calm conscience, and of a simple belief in the efficacy of prayer. Over every such life – over all the grief that may be, all the temptation that must be – is the purifying hope of a great Advent, the ennobling assurance of a perfect victory, the knowledge that if we continue true to the principle of our new birth we are safe. And our safety is, not that we keep ourselves, but that we are kept by arms which are as soft as love, and as strong as eternity.[123]

These Epistles are full of instruction and of comfort for us, just because they are written in an atmosphere of the Church which, in one respect at least, resembles our own. There is in them no reference whatever to a continuance of miraculous powers, to raptures, or to extraordinary phenomena. All in them which is supernatural continues even to this day, in the possession of an inspired record, in sacramental grace, in the pardon and holiness, the peace and strength of believers. The apocryphal "Acts of John" contain some fragments of real beauty almost lost in questionable stories and prolix declamation. It is probably not literally true that when St. John in early life wished to make himself a home, his Lord said to him, "I have need of thee, John;" that that thrilling voice once came to him, wafted over the still darkened sea – "John, hadst thou not been Mine, I would have suffered thee to marry."[124] But the Epistle shows us much more effectually that he had a pure heart and virgin will. It is scarcely probable that the son of Zebedee ever drained a cup of hemlock with impunity; but he bore within him an effectual charm against the poison of sin.[125] We of this nineteenth century may smile when we read that he possessed the power of turning leaves into gold, of transmuting pebbles into jewels, of fusing shattered gems into one; but he carried with him wherever he went that most excellent gift of charity, which makes the commonest things of earth radiant with beauty.[126] He may not actually have praised his Master during his last hour in words which seem to us not quite unworthy even of such lips – "Thou art the only Lord, the root of immortality, the fountain of incorruption. Thou who madest our rough wild nature soft and quiet, who deliveredst me from the imagination of the moment, and didst keep me safe within the guard of that which abideth for ever." But such thoughts in life or death were never far from him for whom Christ was the Word and the Life; who knew that while "the world passeth away and the lust thereof, he that doeth the will of God abideth for ever."[127]

May we so look upon this image of the Apostle's soul in his Epistle that we may reflect something of its brightness! May we be able to think, as we turn to this threefold assertion of knowledge – "I know something of the security of this keeping.[128] I know something of the sweetness of being in the Church, that isle of light surrounded by a darkened world.[129] I know something of the beauty of the perfect human life recorded by St. John, something of the continued presence of the Son of God, something of the new sense which He gives, that we may know Him who is the Very God."[130] Blessed exchange not to be vaunted loudly, but spoken reverently in our own hearts – the exchange of we, for I. There is much divinity in these pronouns.[131]

NOTESNote A1 John iv. 8, 9, 10. Modern theological schools of a Calvinistic bias have tended to overlook the conception of the nature of God as essential or substantive Love, and to consider love only as manifested in redemption. Socinianising interpreters understand the proposition to mean that God is simply and exclusively benevolent. (On the inadequacy of this, see Butler, Anal., Part I., ch. iii., and Dissertation II. of the Nature of Virtue.) The highest Christian thought has ever recognised that the proposition 'God is Love' necessarily involves the august truth that God if sole is not solitary. ("Credimur et confitemur omnipotentem Trinitatem – unum Deum solum non solitarium." Concil. Tolet., vi. 1.) "Let it not be supposed," said St. Bernard, "that I here account Love as an attribute or accident, but as the Divine essence – no new doctrine, seeing that St. John saith 'God is love.' It may rightly be said both that Love is God, and that love is the gift of God. For Love gives love; the essential Love gives that which is accidental. When Love signifies the Giver, it is the name of His essence; when it signifies His gift, it is the name of a quality or attribute." (S. Bernard., de dil. Deo, xii.). "This is nobly said. God is love. Thus love is the eternal law whereby all things were created and are governed – wherewith He who is the law of all things is unto Himself His own law, and that a law of love – wherewith He bindeth His Trinity into Unity." (Thomassin. Dogm. Theol., lib. iii., 23.)

Note Bἡ ῥιζα της αθανασιας και ἡ πηγη της αφθαρσιας· ὁ την ερημον και αγριωθεισαν φυσιν ἡμων ηρεμον και ἡσυχιον ποιησας, ὁ της προσκαιρου φαντασιας ῥυσαμενος με και εις την αει μενουσαν φρουρησας (Acta Johannis, 21). These sentences are surely not without freshness and power. One other passage is worth translating, because it seems to have just that imaginative cast which makes the Greek Liturgies, like so much else that is Greek, stand midway between the East and West; and because it apparently refers to St. John's Gospel. "Jesus! Thou who hast woven this coronal with Thy plaiting, who hast blended these many flowers into the flower of Thy presence, not blown through by the winds of any storm; Thou who hast scattered thickly abroad the seed of these words of Thine" – (Acta Johannis, 17).

PART II

SOME GENERAL RULES FOR THE INTERPRETATION OF THE FIRST EPISTLE OF ST. JOHN

I. Subject Matter(1) The Epistle is to be read through with constant reference to the Gospel. In what precise form the former is related to the latter (whether as a preface or as an appendix, as a spiritual commentary or an encyclical) critics may decide. But there is a vital and constant connection. The two documents not only touch each other in thought, but interpenetrate each other; and the Epistle is constantly suggesting questions which the Gospel only can answer, e. g., 1 John i. 1, cf. John i. 1-14; 1 John v. 9, "witness of men," cf. John i. 15-36, 41, 45, 49, iii. 2, 27-36, iv. 29-42, vi. 68, 69, vii. 46, ix. 38, xi. 27, xviii. 38, xix. 5, 6, xx. 28.

(2) Such eloquence of style as St. John possesses is real rather than verbal. The interpreter must look not only at the words themselves, but at that which precedes and follows; above all he must fix his attention not only upon the verbal expression of the thought, but upon the thought itself. For the formal connecting link is not rarely omitted, and must be supplied by the devout and candid diligence of the reader. The "root below the stream" can only be traced by our bending over the water until it becomes translucent to us.

E.g. 1 John i. 7, 8. Ver. 7, "the root below the stream" is a question of this kind, which naturally arises from reading ver. 6 – "must it be said that the sons of light need a constant cleansing by the blood of Jesus, which implies a constant guilt"? Some such thought is the latent root of connection. The answer is supplied by the following verse. ["It is so" for] "if we say that we have no sin," etc. Cf. also iii. 16, 17, xiv. 8, 9, 10, 11, v. 3 (ad. fin.), 4.

II. Language1. Tenses.

In the New Testament generally tenses are employed very much in the same sense, and with the same general accuracy, as in other Greek authors. The so-called "enallage temporum," or perpetual and convenient Hebraism, has been proved by the greatest Hebrew scholars to be no Hebraism at all. But it is one of the simple secrets of St. John's quiet thoughtful power, that he uses tenses with the most rigorous precision.

(a) The Present of continuing uninterrupted action, e. g., i. 8, ii. 6, iii. 7, 8, 9.

Hence the so-called substantized participle with article ὁ has in St. John the sense of the continuous and constitutive temper and conduct of any man, the principle of his moral and spiritual life —e. g., ὁ λεγων, he who is ever vaunting, ii. 4; πας ὁ μισων, every one the abiding principle of whose life is hatred, iii. 15; πας ὁ αγαπων, every one the abiding principle of whose life is love, iv. 7.

The Infin. Present is generally used to express an action now in course of performing or continued in itself or in its results, or frequently repeated – e.g., 1 John ii. 6, iii. 8, 9, v. 18. (Winer, Gr. of N. T. Diction, Part 3, xliv., 348).

(b) The Aorist.

This tense is generally used either of a thing occurring only once, which does not admit, or at least does not require, the notion of continuance and perpetuity; or of something which is brief and as it were only momentary in duration (Stallbaum, Plat. Enthyd., p. 140). This limitation or isolation of the predicated action is most accurately indicated by the usual form of this tense in Greek. The aorist verb is encased between the augment ε- past time, and the adjunct σ- future time, i. e., the act is fixed on within certain limits of previous and consequent time (Donaldson, Gr. Gr., 427, B. 2). The aorist is used with most significant accuracy in the Epistle of St. John, e. g., ii. 6, 11, 27, iv. 10, v. 18.

(c) The Perfect.

The Perfect denotes action absolutely past which lasts on in its effects. "The idea of completeness conveyed by the aorist must be distinguished from that of a state consequent on an act, which is the meaning of the perfect" (Donaldson, Gr. Gr., 419). Careful observation of this principle is the key to some of the chief difficulties of the Epistle (iii. 9, v. 4, 18).

(2) The form of accessional parallelism is to be carefully noticed. The second member is always in advance of the first; and a third is occasionally introduced in advance of the second, denoting the highest point to which the thought is thrown up by the tide of thought, e. g., 1 John ii. 4, 5, 6, v. 11, v. 27.

(3) The preparatory touch upon the chord which announces a theme to be amplified afterwards, —e. g., ii. 29, iii. 9 – iv. 7, v. 3, 4; iii. 21 – v. 14, ii. 20, iii. 24, iv. 3, v. 6, 8, ii. 13, 14, iv. 4 – v. 4, 5.

(4) One secret of St. John's simple and solemn rhetoric consists in an impressive change in the order in which a leading word is used, e. g., 1 John ii. 24, iv. 20.

These principles carefully applied will be the best commentary upon the letter of the Apostle, to whom not only when his subject is —

"De Deo Deum verumAlpha et Omega, Patrem rerum";but when he unfolds the principles of our spiritual life, we may apply Adam of St. Victor's powerful and untranslatable line,

"Solers scribit idiota."SECTION I

DISCOURSE I.

ANALYSIS AND THEORY OF ST. JOHN'S GOSPEL

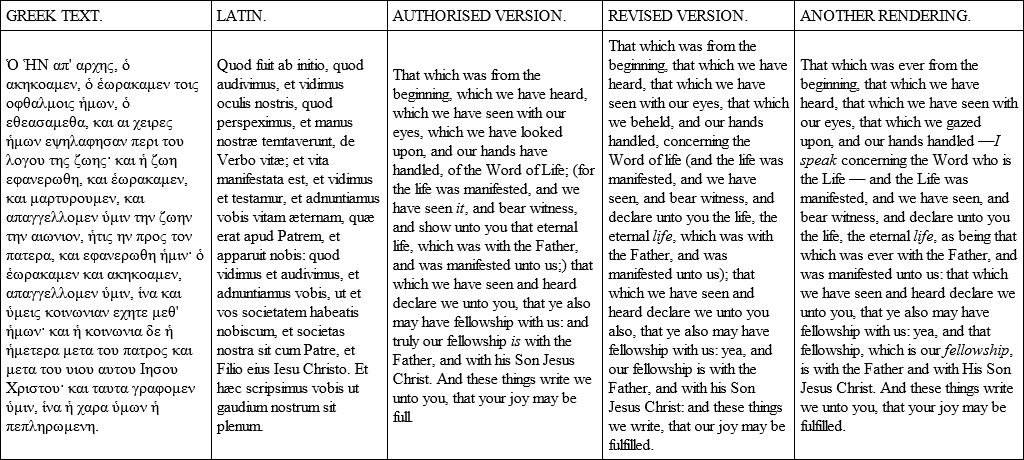

"Of the Word of Life." – 1 John i. 1In the opening verses of this Epistle we have a sentence whose ample and prolonged prelude has but one parallel in St. John's writings.[132] It is, as an old divine says, "prefaced and brought in with more magnificent ceremony than any passage in Scripture."

The very emotion and enthusiasm with which it is written, and the sublimity of the exordium as a whole, tends to make the highest sense also the most natural sense. Of what or of whom does St. John speak in the phrase "concerning the Word of Life," or "the Word who is the Life"? The neuter "that which" is used for the masculine – "He who" – according to St. John's practice of employing the neuter comprehensively when a collective whole is to be expressed. The phrase "from the beginning," taken by itself, might no doubt be employed to signify the beginning of Christianity, or of the ministry of Christ. But even viewing it as entirely isolated from its context of language and circumstance, it has a greater claim to be looked upon as from eternity or from the beginning of the creation. Other considerations are decisive in favour of the last interpretation.

(1) We have already adverted to the lofty and transcendental tone of the whole passage, elevating as it does each clause by the irresistible upward tendency of the whole sentence. The climax and resting place cannot stop short of the bosom of God. (2) But again, we must also bear in mind that the Epistle is everywhere to be read with the Gospel before us, and the language of the Epistle to be connected with that of the Gospel. The proœmium of the Epistle is the subjective version of the objective historical point of view which we find at the close of the preface to the Gospel. "The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us;" so St. John begins his sentence in the Gospel with a statement of an historical fact. But he proceeds, "and we delightedly beheld His glory;" that is a statement of the personal impression attested by his own consciousness and that of other witnesses. But let us note carefully that in the Epistle, which is in subjective relation to the Gospel, this process is exactly reversed. The Apostle begins with the personal impression; pauses to affirm the reality of the many proofs in the realm of fact of that which produced this impression through the senses upon the conceptions and emotions of those who were brought into contact with the Saviour; and then returns to the subjective impression from which he had originally started. (3) Much of the language in this passage is inconsistent with our understanding by the Word the first announcement of the Gospel preaching. One might of course speak of hearing the commencement of the Gospel message, due surely not of seeing and handling it. (4) It is a noteworthy fact that the Gospel and the Apocalypse begin with the mention of the personal Word. This may well lead us to expect that Logos should be used in the same sense in the proœmium of the great Epistle by the same author.

We conclude then that when St. John here speaks of the Word of Life, he refers to something higher again than the preaching of life, and that he has in view both the manifestation of the life which has taken place in our humanity, and Him who is personally at once the Word and the Life.[133] The proœmium may be thus paraphrased. "That which in all its collective influence was from the beginning as understood by Moses, by Solomon, and Micah;[134] which we have first and above all heard in divinely human utterances, but which we have also seen with these very eyes; which we gazed upon with the full and entranced sight that delights in the object contemplated;[135] and which these hands handled reverentially at His bidding.[136] I speak all this concerning the Word who is also the Life."

Tracts and sheets are often printed in our day with anthologies of texts which are supposed to contain the very essence of the Gospel. But the sweetest scents, it is said, are not distilled exclusively from flowers, for the flower is but an exhalation. The seeds, the leaf, the stem, the very bark should be macerated, because they contain the odoriferous substance in minute sacs. So the purest Christian doctrine is distilled, not only from a few exquisite flowers in a textual anthology, but from the whole substance, so to speak, of the message. Now it will be observed that at the beginning of the Epistle which accompanied the fourth Gospel, our attention is directed not to a sentiment, but to a fact and to a Person. In the collections of texts to which reference has been made, we should probably never find two brief passages which may not unjustly be considered to concentrate the essence of the scheme of salvation more nearly than any others. "The Word was made flesh." "Concerning the Word of Life (and that Life was once manifested, and we have seen and consequently are witnesses and announce to you from Him who sent us that Life, that eternal Life whose it is to have been in eternal relation with the Father, and manifested to us); That which we have seen and heard declare we from Him who sent us unto you, to the end that you too may have fellowship with us."

It would be disrespectful to the theologian of the New Testament to pass by the great dogmatic term never, so far as we are told, applied by our Lord to Himself, but with which St. John begins each of his three principal writings – The Word.[137]

Such mountains of erudition have been heaped over this term that it has become difficult to discover the buried thought. The Apostle adopted a word which was already in use in various quarters simply because if, from the nature of the case necessarily inadequate,[138] it was yet more suitable than any other. He also, as profound ancient thinkers conceived, looked into the depths of the human mind, into the first principles of that which is the chief distinction of man from the lower creation – language. The human word, these thinkers taught, is twofold; inner and outer – now as the manifestation to the mind itself of unuttered thought, now as a part of language uttered to others. The word as signifying unuttered thought, the mould in which it exists in the mind, illustrates the eternal relation of the Father to the Son. The word as signifying uttered thought illustrates the relation as conveyed to man by the Incarnation. "No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten God which is in the bosom of the Father He interpreted Him." For the theologian of the Church Jesus is thus the Word; because He had His being from the Father in a way which presents some analogy to the human word, which is sometimes the inner vesture, sometimes the outward utterance of thought – sometimes the human thought in that language without which man cannot think, sometimes the speech whereby the speaker interprets it to others. Christ is the Word Whom out of the fulness of His thought and being the Father has eternally inspoken and outspoken into personal existence.[139]