полная версия

полная версияExpositor's Bible: The Epistles of St. John

Enough, and more than enough of this. The monster of ignorance who has never learnt a prayer, has hitherto been looked upon as one of the saddest of sights. But there is something sadder – the monster of over-cultivation, the wreck of schools, the priggish fanatic of godlessness. Alas! for the nature which has become like a plant artificially trained and twisted to turn away from the light. Alas! for the heart which has hardened itself into stone until it cannot beat faster, or soar higher, even when men are saying with happy enthusiasm, or when the organ is lifting upward to the heaven of heavens the cry which is at once the creed of an everlasting dogma and the hymn of a triumphant hope – "with Thee is the well of Life, and in Thy light shall we see light." Now having heard the answer of the modern spirit to the question "what is the real value of prayer?" think of the answer of the spirit of the Church as given by St. John in this paragraph. That answer is not drawn out in a syllogism. St. John appeals to our consciousness of a divine life. "That ye may know that ye have eternal life." This knowledge issues in confidence, i.e., literally the sweet possibility of saying out all to God. And this confidence is never disappointed for any believing child of God. "If we know that He hear us, we know that we have the petitions that we desired of Him."[345]

On the 16th verse we need only say, that the greatness of our brother's spiritual need does not cease to be a title to our sympathy. St. John is not speaking of all requests, but of the fulness of brotherly intercession.

One question and one warning in conclusion; and that question is this. Do we take part in this great ministry of love? Is our voice heard in the full music of the prayers of intercession that are ever going up to the Throne, and bringing down the gift of life? Do we pray for others?

In one sense all who know true affection and the sweetness of true prayer do pray for others. We have never loved with supreme affection any for whom we have not interceded, whose names we have not baptized in the fountain of prayer. Prayer takes up a tablet from the hand of love written over with names; that tablet death itself can only break when the heart has turned Sadducee.

Jesus (we sometimes think) gives one strange proof of the love which yet passeth knowledge. "Now Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus;" "when He had heard therefore" [O that strange therefore!] "that Lazarus was sick, He abode two days still in the same place where He was." Ah! sometimes not two days, but two years, and sometimes evermore, He seems to remain. When the income dwindles with the dwindling span of life; when the best beloved must leave us for many years, and carries away our sunshine with him; when the life of a husband is in danger – then we pray; "O Father, for Jesu's sake spare that precious life; enable me to provide for these helpless ones; bless these children in their going out and coming in, and let me see them once again before the night cometh, and my hands are folded for the long rest." Yes, but have we prayed at our Communion "because of that Holy Sacrament in it, and with it," that He would give them the grace which they need – the life which shall save them from sin unto death? Round us, close to us in our homes, there are cold hands, hearts that beat feebly. Let us fulfil St. John's teaching, by praying to Him who is the life that He would chafe those cold hands with His hand of love, and quicken those dying hearts by contact with that wounded heart which is a heart of fire.

NOTESCh. v. 3-17Ver. 3. This section should begin with the words "And His commandments are not heavy" – and should not be separated from what follows, because they give one reason of the victory whereof he proceeds to speak. "His commandments are not heavy, for all that is born of God conquereth the world." What a picture of the sweetness of a life of service! What a gentle smile must have been on the old man's face as he said, "His commandments are not grievous!"

Vers. 7, 8. This passage with its apparent obscurity, and famous interpolation, demands some additional notice. As to criticism and interpretation.

(1) Critically. Since the publication of J. J. Griesbach's celebrated work (Diatribe in locum 1 John v. 7, 8, Tom. ii., N.T. Halle: 1806), first German, and latterly English, opinion has become absolutely unanimous in agreeing with Griesbach that "the words included between brackets are spurious, and should therefore be eliminated from the Sacred Text." Even the famous Roman Catholic scholar, Scholts, in his great critical edition of the New Testament, in two volumes (Bonn: 1836), boldly dropped the disputed passage from the text. The interpolated passage has certainly no support in any uncial manuscript, or ancient version, or Greek Father of the four first centuries. (2) As to interpretation, the faith has lost nothing by the honesty of her wisest defenders. The whole of the genuine passage is intensely Trinitarian. The interpolation is nothing but an exposition written into the text. The three genuine witnesses do really point to the Three Witnesses in Heaven. Bengel's saying expresses the permanent feeling of Christendom, which no criticism can do away with: "This trine array of witnesses on earth is supported by, and has above and beneath it the Trinity, which is Heavenly, archetypal, fundamental, everlasting." The whole context recognizes three special works of the Three Persons of the Blessed Trinity. "This is the witness of God," i. e. of the Father (ver. 9); "this is He that came by water and blood," i. e. the Son (ver. 6); "it is the Spirit that witnesseth," i. e. the Holy Ghost (ibid.).

A fuller examination of this passage, from a polemical point of view, will be found in the third of the introductory discourses. It will be well, however, to indicate here the immediate controversial reference in the Spirit, the water, and the blood. There is abundant proof that the popular heretical philosophy of Asia Minor struck Christianity precisely in three vital places. It denied —

(1) The Incarnation – consequently

(2) The Redemption – consequently

(3) The Sacraments.

But the mention of the water and the blood in connection with the Person of the Son Incarnate and Crucified established exactly these three points. Narrated as it was by an eye-witness, it established: —

(1) The reality of the Incarnation – consequently

(2) The reality of Redemption – for the blood of Jesus cleanses from all sin (1 John i. 7) – consequently

(3) The reality of Sacraments.

We have articulate evidence of the denial of the two sacraments by the Docetic idealists of Asia Minor. The Philosophumena tells us of the view of baptism held by one of their principal sects. "According to them the promise of the laver of regeneration is nothing more than the introduction into the 'unfading pleasure' of him that is washed (as they say) with living water, and anointed with 'chrism that speaketh not.'"[346] The testimony of Ignatius is express as to the other sacrament. "From Eucharist and prayer they abstain on account of not confessing that the Eucharist is flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ which suffered for our sins." ["Water and blood" should be noted in Heb. ix. 19. Water is not mentioned in Exod. xxiv. 6.] – (Ep. ad Smyrn. vii.)

SECTION X

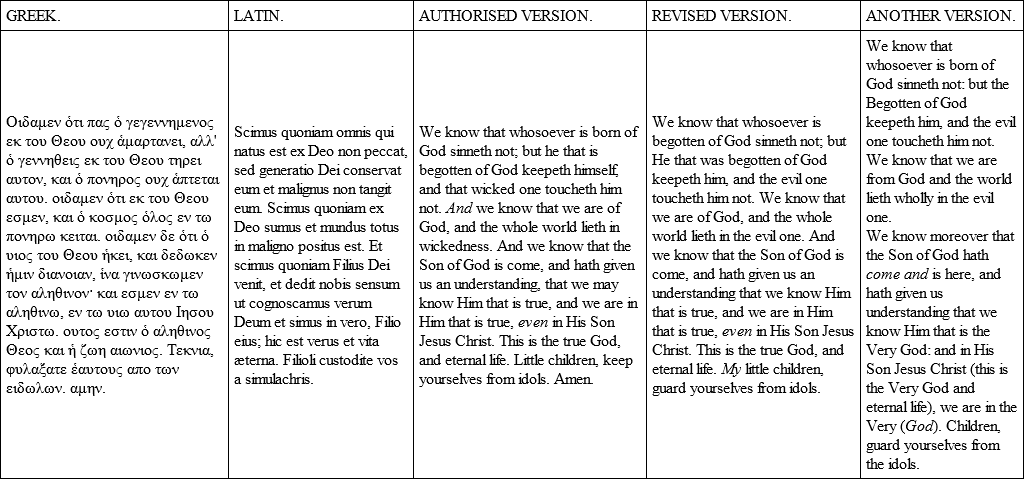

Ver. 18, 19, 20. Three seals are affixed to the close of this Epistle – three postulates of the spiritual reason; three primary canons of spiritual perception and knowledge. Each is marked by the emphatic "we know," which is stamped at the opening its first line. The first "we know," is of a sense of purity made possible to the Christian through the keeping by Him Who is the one Begotten of God. The evil one cannot touch him with the contaminating touch which implies connection. The second "we know" involves a sense of privilege; the true conviction that by God's power, and love, we are brought into a sphere of light, out of the darkness in which a sinful world has become as if cradled on the lap of the evil one. The third "we know" is the deep consciousness of the very Presence of the Son of God in and with His Church. And with this comes all the inner life – supremely a new way of looking at things, a new possibility of thought, a new cast of thought and sentiment, "understanding" (διανοια). Words denoting intellectual faculties and processes are rare in St. John. This word is used in the sense just given in Plat., Rep., 511, and Arist., Poet., vi. (in the last, however, rather of the sentiment of the piece than of the author), "He hath given us understanding that we know continuously the very [God]." And in "His Son Jesus Christ [this is the very God and eternal life] we are in the very God." This interpretation of the passage is supported by the position of the pronoun which cannot be referred naturally to any subject but Jesus Christ. Waterland quotes Irenæus. "No man can know God unless God has taught him; that is to say, that without God, God cannot be known."[347]

Ver. 21. The Epistle closes with a short, sternly affectionate exhortation. "Children, guard yourselves" (the aorist imperative of immediate final decision) "from the idols." These words are natural in the atmosphere of Ephesus (Acts xix. 26, 27). The Author of the Apocalypse has a like hatred of idols. (Apoc. ii. 14, 15, ix. 20, xx. 1-8, xxii. 15.)

It would appear that the Gnostics allowed people to eat freely things sacrificed to idols. Modern, like ancient unbelief, has sometimes attributed to St. John a determination to exalt the Master whom he knew to be a man to an equality with God. But this is morally inconsistent with the Apostle's unaffected shrinking from idolatry in every form. (See Speaker's Commentary, N. T., iv., 347).

THE SECOND EPISTLE OF ST. JOHN.

II. EPISTLE

DISCOURSE XVI.

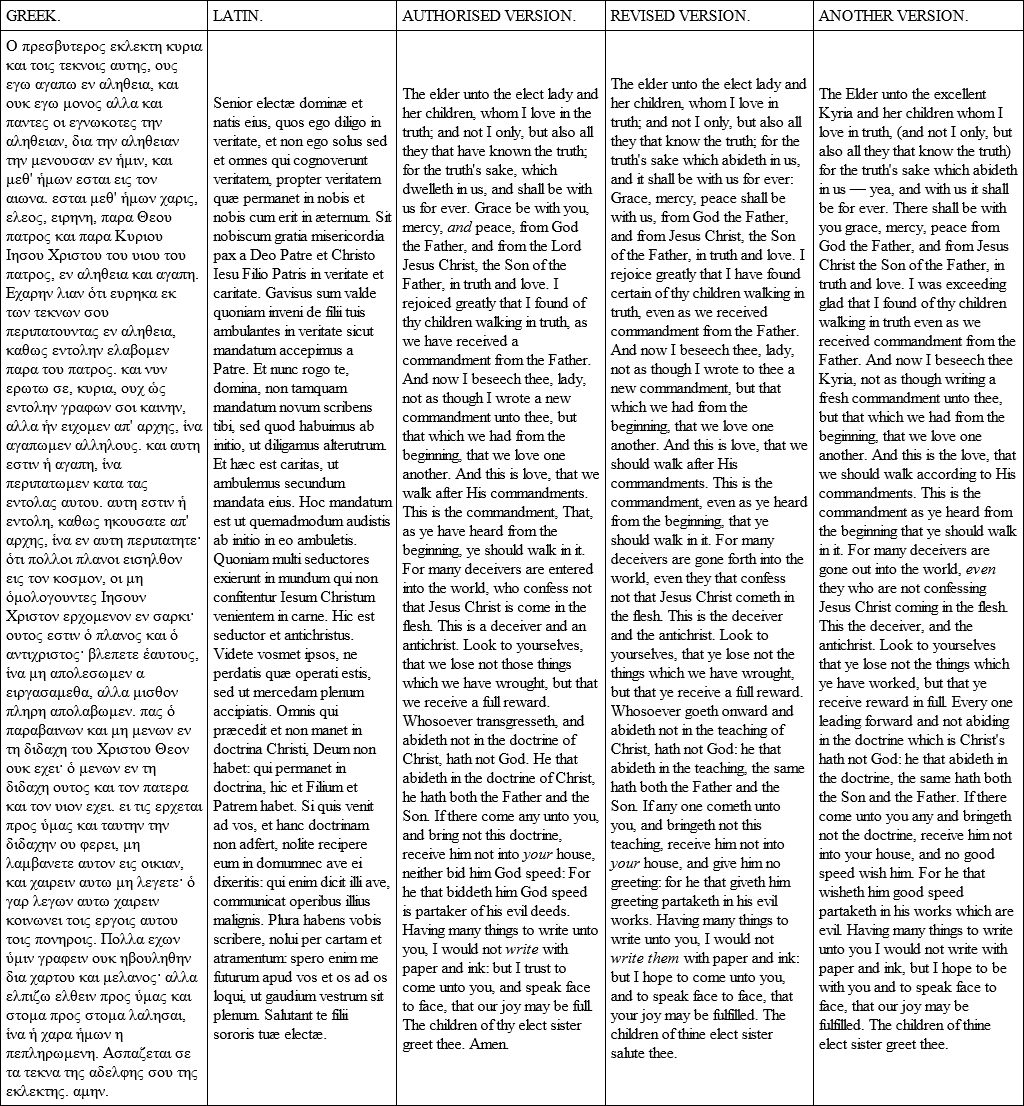

THEOLOGY AND LIFE IN KYRIA'S LETTER

"The elder unto the elect lady and her children, whom I love in the truth … Grace be with you, mercy and peace, from God the Father and from the Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of the Father, in truth and love." – 2 John, 3.

Of old God addressed men in tones that, were so to speak, distant. Sometimes He spoke with the stern precision of law or ritual; sometimes in the dark and lofty utterances of prophets; sometimes through the subtle voices of history, which lend themselves to different interpretations. But in the New Testament He whom no man hath seen at any time, "interpreted,"[348] Himself with a sweet familiarity. It is of a piece with the dispensation of condescension, that the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven should come to us in such large measure through epistles. For a letter is just the result of taking up one's pen to converse with one who is absent, a familiar talk with a friend.

Of the epistles in our New Testament, a few are addressed to individuals. The effect of three of these letters upon the Church, and even upon the world, has been great. The Epistles to Timothy and Titus, according to the most prevalent interpretation of them, have been felt in the outward organization of the Church. The Epistle to Philemon, with its eager tenderness, its softness as of a woman's heart, its chivalrous courtesy, has told in another direction. With all its freedom from the rashness of social revolution; its almost painful abstinence (as abolitionists have sometimes confessed to feeling) from actual invective against slavery in the abstract; that letter is yet pervaded by thoughts whose issue can only be worked out by the liberty of the slave. The word emancipation may not be pronounced, but it hovers upon the Apostle's lips.

The second Epistle is, in our judgment, a letter to an individual. Certainly we are unable to find in its whole contents any probable allusion to a Church personified as a lady.[349] It is, as we read it, addressed to Kyria, an Ephesian lady, or one who lived in the circle of Ephesian influence. It was sent by the Apostle during an absence from Ephesus. That absence might have been for the purpose of one of the visitations of the Churches of Asia Minor, which (as we are told by ancient Church writers) the Apostle was in the habit of holding. Possibly, however, in the case of a writer so brief and so reserved in the expression of personal sentiment as St. John, the gush and sunshine of anticipated joy at the close of this note might tempt us to think of a rift in some sky that had been long darkened; of the close of some protracted separation, soon to be forgotten in a happy meeting. "Having many things to write unto you, I would not do so by means of paper and ink; but I hope to come unto you, and to speak face to face that our joy may be fulfilled."[350] The expression might not seem unsuitable for a return from exile. Several touches of language and feeling in the latter point to the conclusion that Kyria was a widow. There is no mention of her husband, the father of her children. In the case of a writer who uses the names of God with such subtle and tender suitability, the association of Kyria's "children walking in truth" with "even as we received commandment from the Father," may well point to Him who was for them the Father of the fatherless. We need not with some expositors draw the sad conclusion that St. John affectionately hints that there were others of the family who could not be included in this joyful message. But it would seem highly probable from the language used that there were several sons, and also that Kyria had no daughters. Over these sons who had lost one earthly parent, the Apostle rejoices with the heart of a father in God. He bursts out with his eureka, the eureka not of a philosopher, but of a saint. "I rejoiced exceedingly that I found[351] certain of the number of thy children walking in truth."

While we may not trace in this little Epistle the same fountain of wide-spreading influence as in others to which we have referred; while we feel that, like its author, its work is deep and silent rather than commanding, reflection will also lead us to the conclusion that it is worthy of the Apostle who was looked upon as one of the "pillars" of the faith.[352]

1. Let us reflect that this letter is addressed by the aged Apostle to a widow, and concerns her family.

It is significant that Kyria was, in all probability, a widow of Ephesus.

Too many of us have more or less acquaintance with one department of French literature. A Parisian widow is too often the questionable heroine of some shameful romance, to have read which is enough to taint the virginity of the young imagination. Ephesus was the Paris of Ionia. Petronius was the Daudet or Zola of his day. An Ephesian widow is the heroine of one of the most cynically corrupt of his stories.

But "where sin abounded, grace did more than abound." Strange that first in an epistle to a Bishop of the Church of Ephesus, St. Paul should have presented us with that picture of a Christian widow – "she that is a widow, indeed, and desolate, who hath her hope set on God, and continueth in prayer night and day" – yet who, if she has the devotion, the almost entire absorption in God, of Anna, the daughter of Phanuel,[353] leaves upon the track of her daily road to heaven the trophies of Dorcas – "having brought up children well, used hospitality to strangers, washed the saints' feet, relieved the afflicted, diligently followed every good work."[354] Such widows are the leaders of the long procession of women, veiled or unveiled, with vows or without them, who have ministered to Jesus through the ages. Christ has a beautiful art of turning the affliction of His daughters into the consolation of suffering. When life's fairest hopes are disappointed by falsehood, by cruel circumstances, by death; the broken heart is soothed by the love of Christ, the only love which is proof against death and change. The consolation thus received is the most unselfish of gifts. It overflows, and is lavishly poured out upon the sick and weary. With St. Paul's picture of a widow of this kind, contrast another by the same hand which hangs close beside it. The younger Ephesian widow, such as Petronius described, was known by St. Paul also. If any count the Apostle as a fanatic, destitute of all knowledge of the world because he lived above it, let them look at those lines, which are full of such caustic power, as they hit on the characteristics of certain idle and wanton affecters of a sorrow which they never felt.[355] What a distance between such widows and Kyria, "beloved for the truth's sake which abideth in us!"[356]

But the short letter of St. John is addressed to Kyria's family as well as to herself. "The elder to the excellent Kyria and her children."[357]

There is one question which we naturally ask about every school and form of religion. It is the question which a great English Professor of Divinity used to ask his pupils to put in a homely form about every religious scheme and mode of utterance – "will it wash well?" Is it an influence which seems to be productive and lasting? Does it abide through time and trials? Is it capable of being passed on to another generation? Are plans, services, organizations, preachings, classes, vital or showy? Are they fads to meet fancies, or works to supply wants? Is that which we hold such sober, solid truth, that wise piety can say of it, half in benediction, half in prophecy[358]– "the truth which abideth in us; yea, and with us it shall be for ever?"

2. We turn to the contents of the Epistle.

We shall be better able to appreciate the value of these, if we consider the state of Christian literature at that time.

What had Christians to read and carry about with them? The excellent work of the Bible Society was physically impossible for long centuries to come. No doubt the LXX. version of the Old Testament was widely spread. In every great city of the Roman Empire there was a vast population of Jews. Many of these were baptized into the Church, and carried into it with them their passionate belief in the Old Testament. The Christians of the time and place to which we refer could, probably, with little trouble, if not read, yet hear the Old Covenant and able expositions of it. But they had not copies of the entire New Testament. Indeed, if all the New Testament was then written, it certainly was not collected into one volume, nor constituted one supreme authority. "Many barbarous nations," says a very ancient Father, "believe in Christ without written record, having salvation impressed through the Spirit in their hearts, and diligently preserving the old tradition."[359] Possibly a Church or single believer had one synoptical Gospel. At Ephesus Christians had doubtless been catechised in, and were deeply imbued with, St. John's view of the Person, work, and teaching of our Lord. This had now been moulded into shape, and definitely committed to writing in that glorious Gospel, the Church's Holy of Holies, St. John's Gospel. For them and for their contemporaries there was a living realization of the Gospel. They had heard it from eye-witnesses. They had passed into the wonderland of God. The earth on which Jesus trod had blossomed into miracle. The air was haunted by the echoes of His voice. They had, probably, also a certain number of the Epistles of St. Paul. The Christians of Ephesus would have a special interest in their own Epistle to the Ephesians, and in the two which were written to their first Bishop, Timothy. They had also (whether written or not) impressed upon their memories by their weekly Eucharist, the liturgical Canon of consecration according to the Ephesian usage– from which, and not from the Roman, the Spanish and Gallican seem to be derived. The Ephesian Christians had also the first Epistle of St. John, which in some form accompanied the Gospel, and is, indeed, a picture of spiritual life drawn from it. But let us remember that the Epistle is not of a character to be very quickly or readily learned by heart. Its subtle, latent links of connection do not present many grappling hooks for the memory to fasten itself to. Copies also must have been comparatively few.

Now let us see how the second Epistle may well have been related to the first.

Supremely, and above all else, the first Epistle contained three warnings, very necessary for those times. (1) There was a danger of losing the true Christ, the Word made Flesh, Who for the forgiveness of our sins did shed out of His most precious side both water and blood – in a false, because shadowy and ideal Christ. (2) There was danger of losing true love, and therefore spiritual life, with truth. (3) With the true Christ and true love there was a danger of losing the true commandment– love of God and of the brethren. Now in the second Epistle these very three warnings were written on a leaflet in a form more calculated for circulation and for remembrance. (1) Against the peril of faith, of losing the true Christ. "Many deceivers are gone out into the world – they who confess not Jesus Christ coming in flesh. This is the deceiver and the antichrist."[360] With the true Christ, the true doctrine of Christ would also vanish, and with it all living hold upon God. Progress was the watchword; but it was in reality regress. "Every one who abideth not in the doctrine of Christ hath not God."[361] (2) Against the peril of losing love. "I beseech thee, Kyria … that we love one another."[362] (3) Against the peril of losing the true commandment (the great spiritual principle of charity), or the true commandments[363] (that principle in the details of life). "And this is love, that we walk after His commandments. This is the commandment, that even as ye heard from the beginning ye should walk in it."[364]

Here then were the chief practical elements of the first Epistle contracted into a brief and easily remembered shape.

Easily remembered, too, was the stern, practical prohibition of the intimacies of hospitality with those who came to the home of the Christian, in the capacity of emissaries of the antichrist above indicated. "Receive him not into your house, and good speed salute him not with."[365]

Many are offended with this. No doubt Christianity is the religion of love – "the epiphany of the sweet-naturedness and philanthropy of God."[366] We very often look upon heresy or unbelief with the tolerance of curiosity rather than of love. At all events, the Gospel has its intolerance as well as tolerance. St. John certainly had this. It is not a true conception in art which invests him with the mawkish sweetness of perpetual youth. There is a sense in which he was a son of Thunder to the last. He who believes and knows must formulate a dogma. A dogma frozen by formality, or soured by hate, or narrowed by stupidity, makes a bigot. In reading the Church History of the first four centuries we are often tempted to ask, why all this subtlety, this theology-spinning, this dogma-hammering? The answer stands out clear above the mists of controversy. Without all this the Church would have lost the conception of Christ, and thus finally Christ Himself. St. John's denunciations have had a function in Christendom as well as his love.

3. There are two most precious indications of the highest Christian truth with which we may conclude.

We have prefixed to this Epistle that beautiful Apostolic salutation which is found in two only among the Epistles of St. Paul.[367] After that simple, but exquisite expression of blessing merged in prophecy – "the truth which abideth in us – yes! and with us it shall be for ever"[368]– there comes another verse set in the same key. "There shall be with us grace, mercy, peace, from God the Father, and from Jesus Christ the Son of the Father, in truth" of thought, "and love" of life.[369]

This rush and reduplication of words is not very like the usual reserve and absence of emotional excitement in St. John's style. Can it be that something (possibly the glorious death of martyrdom by which Timothy died) led St. John to use words which were probably familiar to Ephesian Christians?