полная версия

полная версияExpositor's Bible: The Epistles of St. John

Now, as we have said above, in distinction from all these fragmentary views, St. John's Epistle is a survey of the completed Christian life, founded upon his Gospel. It is a consummate fruit ripened in the long summers of his experience. It is not a treatise upon the Christian affections, nor a system of doctrine, nor an essay upon works of charity, nor a companion to services.

Yet this wonderful Epistle presupposes at least much that is most precious of all these elements. (1) It is far from being a burst of emotionalism. Yet almost at the outset it speaks of an emotion as being the natural result of rightly received objective truth.[249] St. John recognises feeling, whether of supernatural or natural origin;[250] but he recognises it with a certain majestic reserve. Once only does he seem to be carried away. In a passage to which reference has just been made, after stating the dogma of the Incarnation, he suffuses it with a wealth of emotional colour. It is Christmas in his soul; the bells ring out good tidings of great joy. "These things write we unto you, that your joy may be full." (2) This Epistle is no dogmatic summary. Yet combining its proœmium with the other of the fourth Gospel, we have the most perfect statement of the dogma of the Incarnation. As we read thoughtfully on, dogma after dogma stands out in relief. The divinity of the Word, the reality of His manhood, the effect of His atonement, His intercession, His continual presence, the personality of the Holy Spirit, His gifts to us, the relation of the Spirit to Christ, the Holy Trinity – all these find their place in these few pages. If St. John is no mere doctrinalist he is yet the greatest theologian the Church has ever seen. (3) Once more; if the Apostle's Christianity is no mere humanitarian sentiment to encourage the cultivation of miscellaneous acts of good-nature, yet it is deeply pervaded by a sense of the integral connection of practical love of man with the love of God. So much is this the case, that a large gathering of the most emotional of modern sects is said to have gone on with a Bible reading in St. John's Epistle until they came to the words – "we know that we have passed from death unto life, because we love the brethren." The reader immediately closed the book, pronouncing with general assent that the verse was likely to disturb the peace of the children of God. Still St. John puts humanitarianism in its right place as a result of something higher. "This commandment have we from Him, that he who loveth God love his brother also." As if he would say – "do not sever the law of social life from the law of supernatural life; do not separate the human fraternity from the Divine Fatherhood." (4) No one can suppose that for St. John religion was a mere string of observances. Indeed, to some his Epistle has given the notion of a man living in an atmosphere where external ordinances and ministries either did not exist at all, or only in almost impalpable forms. Yet in that wonderful manual, "The Imitation of Christ," there is not more than the faintest trace of any of these external things; while no one could possibly argue that the author was ignorant of, or lightly esteemed, the ordinances and sacraments amongst which his life must have been spent. Certainly the fourth Gospel is deeply sacramental. This Epistle, with its calm, unhesitating conviction of the sonship of all to whom it is addressed; with its view of the Christian life as in idea a continuous growth from a birth the secret of whose origin is given in the Gospel; with its expressive hints of sources of grace and power and of a continual presence of Christ; with its deep mystical realisation of the double flow from the pierced side upon the cross, and its thrice-repeated exchange of the sacramental order "water and blood,"[251] for the historical order "blood and water"; unquestionably has the sacramental sense diffused throughout it. The Sacraments are not in obtrusive prominence; yet for those who have eyes to see they lie in deep and tender distances. Such is the view of the Christian life in this letter – a life in which Christ's truth is blended with Christ's love; assimilated by thought, exhaling in worship, softening into sympathy with man's suffering and sorrow. It calls for the believing soul, for the devout heart, for the helping hand. It is the perfect balance in a saintly soul of feeling, creed, communion, and work.

For of work for our fellow man it is that the question is asked half despairingly – "whoso hath this world's good, and seeth" (gazes at)[252] "his brother have need, and shutteth up his heart against him, how doth the love of God[253] dwell in him?" Some can quietly look at the poor brother; they see him in need, but they have not the thoughtful eyes that see his need. They may belong to "the sluggard Pity's vision-weaving tribe," who expend a sigh of sentiment upon such spectacles, and nothing more. Or they may be hardened professors of the "dismal science," who have learned to consider a sigh as the luxury of ignorance or of feebleness. But for all practical purposes both these classes interpose a too effectual barrier between their heart and their brother's need. But true Christians are made partakers in Christ of the mystery of human suffering. Even when they are not actually in sight of brethren in want, their ears are ever hearing the ceaseless moaning of the sea of human sorrow, with a sympathy which involves its own measure of pain, though a pain which brings with it abundant compensation. Their inner life has not merely won for itself the partly selfish satisfaction of personal escape from punishment, great as that blessing may be. They have caught something of the meaning of the secret of all love – "we love because He first loved us."[254] In those words is the romance (if we may dare to call it so) of the divine love-tale. Under its influence the face once hard and narrow often becomes radiant and softened; it smiles, or is tearful, in the light of the love of His face who first loved.

It is this principle of St. John which is ever at work in Christian lands. In hospitals it tells us that Christ is ever passing down the wards; that He will have no stinted service; that He must have more for His sick more devotion, a gentler touch, a finer sympathy; that where His hand has broken and blessed, every particle is a sacred thing, and must be treated reverently.

Are there any who are tempted to think that our text has become antiquated; that it no longer holds true in the light of organised charity, of economic science? Let them listen to one who speaks with the weight of years of active benevolence, and with consummate knowledge of its method and duties.[255] "There are men who, in their detestation of roguery, forget that by a wholesale condemnation of charity, they run the risk of driving the honest to despair and of turning them into the very rogues of whom they desire so ardently to be quit. These men are unconsciously playing into the hands of the Socialists and the Anarchists, the only sections of society whose distinct interest it is that misery and starvation should increase. No doubt indiscriminate almsgiving is hurtful to the State as well as to the individual who receives the dole, but not less dangerous would it be to society if the principles of these stern political economists were to be literally accepted by any large number of the rich, and if charity ceased to be practised within the land. We cannot yet afford to shut ourselves up in the castle of philosophic indifference, regardless of the fate of those who have the misfortune to find themselves outside its walls."

NOTESCh. iii. 12-21Ver. 12. A second reference to the Book of Genesis within a few lines (see ver. 8). It is characteristic of the historical spirit of St. John that he does not entangle himself with the luxuriant upgrowth of wild fable in which traditional Judaism has ever enveloped the simple narrative of Cain and Abel in Genesis.

Ver. 15. St. John may refer to another passage in Genesis. "And Esau said in his heart, The days of mourning for my father are at hand; then will I slay my brother Jacob" (Gen. xxvii. 11-41).

Ver. 17. A Rabbinical saying is worth recording as an illustration of the spirit in which the "living of this world" should be held. "He that saith, Mine is thine, and thine is mine, is an idiot; he that saith, Mine is mine, and thine is thine, is moderate; he that saith, Mine is thine, and thine is thine, is charitable; but he that saith, Thine is mine, and mine is mine, is wicked; even though it be only saying it in his heart, to wish it were so." Paulus Fagius. Sentent. Heb.

Vers. 19, 20, 21. These verses probably present more difficulties than any other portion of this Epistle. (1) For their construction. The following note from a fasciculus (now no longer to be procured) written by a master of sacred studies seems to us to say all that can be said for a rendering different from that of the R. V. and our own.

"Ver. 20: ὁτι εαν καταγινωσκη ἡμων ἡ καρδια, ὁτι μειζων εστιν ὁ Θεος. The difficulty is in the second ὁτι, which is ignored by the Vulgate and A. V. The Revisers (after Hoogeveen, De Partic. p. 589, ed. Schütz. and others) point ὁ,τι εαν in the first clause, which they join with the preceding verse: 'and shall assure our heart before him, whereinsoever our heart condemn us; because God' etc. But this is quite inadmissible, since nothing can be plainer than that εαν καταγινωσκη (ver. 20) and εαν μη καταγινωσκη (ver. 21) are both in protasi, and in strict correlation with each other. Dean Alford suggests an ellipsis of the verb substantive before the second ὁτι, and would translate: 'Because if our heart condemn us, (it is) because God' etc. He instances such cases as ει τις εν Χριστω, (he is) καινη κτισις, which are quite dissimilar; but the following from St. Chrysostom (T. X. p. 122 B) fully bears out this construction; Ὁ ζυγος μου χρηστος κ.τ.ἑ. ει δε ουκ αισθανη της κουφοτητος, ὉΤΙ προθυμιαν ερρωμενην ουκ εχεις; where I have expunged δηλον before ὁτι on the authority of three out of four MSS. collated for these Homilies, the fourth, with the old Latin version, for ὁτι προθυμιαν reading μη θαυμασης, προθυμιαν γαρ. In my note on that place I have pointed out that the ellipsis is not of δηλον, but of το αιτιον, causa est, quia. So in the present instance we might translate: 'For if our heart condemn us, (the reason is) because God is greater,' etc., were it not for the difficulty of explaining how the fact of God's being greater than our heart can be a valid reason for our heart condemning us. I would, therefore, take the second ὁτι for quod, not quia, and suppose an ellipsis of δηλον, as in 1 Tim. vi. 7, where see note." —Otium Norvicense, by Frederic Field, M.A., LL.D. (pp. 153, 15).

Dr. Field s rendering then is: "For if our heart condemn us, (it is evident) that God is greater than our heart."

(2) For the meaning of these verses. All interpretations appear to fall into two classes; as St. John is supposed to aim at (a) soothing conscience, or (b) awakening it. But may he not really intend to leave people to think over a something which he has purposely omitted, and to apply it as required? The saying "God is greater than our hearts, and knoweth all things," probably cuts two ways. If my heart condemn me justly, and with truth, much more so does God who is greater than my heart. But, if my conscience is tenderly sensitive, scrupulous because full of love, God's knowledge of my heart tells in this case on the brighter side, as truly as in the other case it told on the darker side. We may lull our heart. "A tranquil God tranquillises all things, and to see His peacefulness is to be at peace." (St. Bernard in Cant.)

SECTION VII

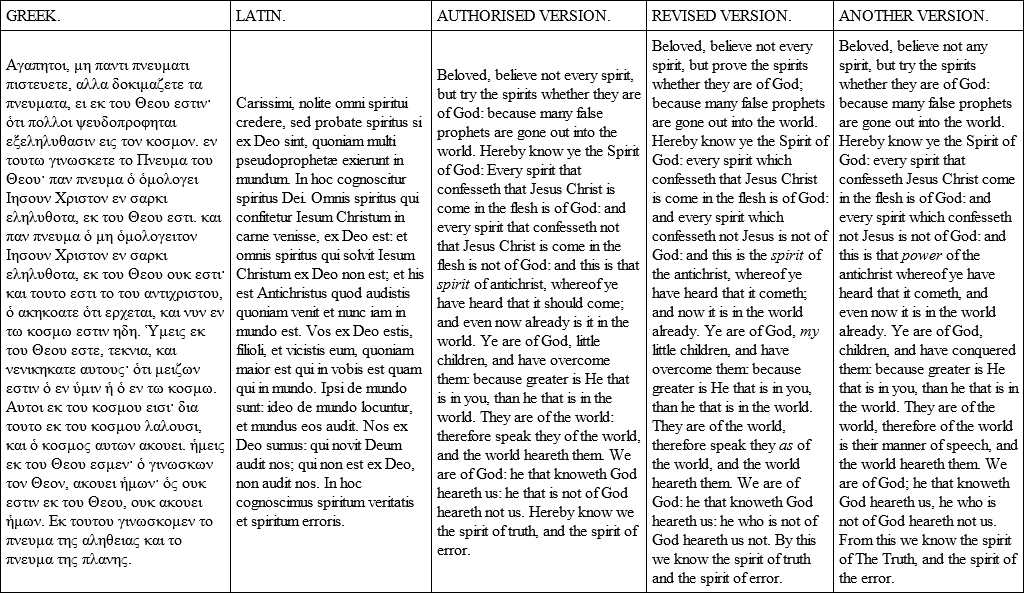

Ver. 1. Believe not any spirit] μη παντι πνευματι πιστευετε. The different constructions of πιστευειν in St. John must be carefully noted. (a) With dative as here – "believe not such an one;" take him not upon trust, at his own word; credit him not with veracity. So in the Gospel, our Lord continually complains that the Jews did not even believe Him on His word – strong and clear as that word was with all the freshness of Heaven, and all the transparency of truth. John v. 38, 46, viii. 45, 46, x. 37.

(b) πιστευειν εις = to make an act of faith in, to repose in as divine. John iii. 36, iv. 39, vi. 35, xi. 25; 1 John v. 10.

(c) With an accusative = to be persuaded of the thing – to believe it with an implied conviction of permanence in the persuasion – as in the beautiful verse (iv. 16) – "we are fully persuaded of the love of God," we make it the creed of our heart. πεπιστευκαμεν την αγαπην.

SECTION VIII

DISCOURSE X.

BOLDNESS IN THE DAY OF JUDGMENT

"Herein is our love made perfect, that we may have boldness in the Day of Judgment: because as He is, so are we in this world." – 1 John iv. 17.

It has been so often repeated that St. John's eschatology is idealized and spiritual, that people now seldom pause to ask what is meant by the words. Those who repeat them most frequently seem to think that the idealized means that which will never come into the region of historical fact, and that the spiritual is best defined as the unreal. Yet, without postulating the Johannic authorship of the Apocalypse – where the Judgment is described with the most awful accompaniments of outward solemnity[256]– there are two places in this Epistle which are allowed to drop out of view, but which bring us face to face with the visible manifestations of an external Advent. It is a peculiarity of St. John's style (as we have frequently seen) to strike some chord of thought, so to speak, before its time; to allow the prelusive note to float away, until suddenly, after a time, it surprises us by coming back again with a fuller and bolder resonance. "And now, my sons,"[257] (had the Apostle said) "abide in Him, that if He shall be manifested, we may have confidence, and not be ashamed shrinking from Him[258] at His coming."[259] In our text the same thought is resumed, and the reality of the Coming and Judgment in its external manifestation as emphatically given as in any other part of the New Testament.[260]

We may here speak of the conception of the Day of the Judgment: of the fear with which that conception is encompassed; and of the sole means of the removal of that fear which St. John recognises.

IWe examine the general conception of "the Day of the Judgment," as given in the New Testament.

As there is that which with terrible emphasis is marked off as "the Judgment,"[261] "the Parousia," so there are other judgments or advents of a preparatory character. As there are phenomena known as mock suns, or haloes round the moon, so there are fainter reflections ringed round the Advent, the Judgment.[262] Thus, in the development of history, there are successive cycles of continuing judgment; preparatory advents; less completed crises, as even the world calls them.

But against one somewhat widely-spread way of blotting the Day of the Judgment from the calendar of the future – so far as believers are concerned – we should be on our guard. Some good men think themselves entitled to reason thus – "I am a Christian. I shall be an assessor in the judgment. For me there is, therefore, no judgment day." And it is even held out as an inducement to others to close with this conclusion, that they "shall be delivered from the bugbear of judgment."

The origin of this notion seems to be in certain universal tendencies of modern religious thought.

The idolatry of the immediate – the prompt creation of effect – is the perpetual snare of revivalism. Revivalism is thence fatally bound at once to follow the tide of emotion, and to increase the volume of the waters by which it is swept along. But the religious emotion of this generation has one characteristic by which it is distinguished from that of previous centuries. The revivalism of the past in all Churches rode upon the dark waves of fear. It worked upon human nature by exaggerated material descriptions of hell, by solemn appeals to the throne of Judgment. Certain schools of biblical criticism have enabled men to steel themselves against this form of preaching. An age of soft humanitarian sentiment – superficial, and inclined to forget that perfect Goodness may be a very real cause of fear – must be stirred by emotions of a different kind. The infinite sweetness of our Father's heart – the conclusions, illogically but effectively drawn from this, of an Infinite good-nature, with its easy-going pardon, reconciliation all round, and exemption from all that is unpleasant – these, and such as these, are the only available materials for creating a great volume of emotion. An invertebrate creed; punishment either annihilated or mitigated; judgment, changed from a solemn and universal assize, a bar at which every soul must stand, to a splendid, and – for all who can say I am saved– a triumphant pageant in which they have no anxious concern; these are the readiest instruments, the most powerful leverage, with which to work extensively upon masses of men at the present time. And the seventh article of the Apostles' Creed must pass into the limbo of exploded superstition.

The only appeal to Scripture which such persons make, with any show of plausibility, is contained in an exposition of our Lord's teaching in a part of the fifth chapter of the fourth Gospel.[263] But clearly there are three Resurrection scenes which may be discriminated in those words. The first is spiritual, a present awakening of dead souls,[264] in those with whom the Son of Man is brought into contact in His earthly ministry. The second is a department of the same spiritual resurrection. The Son of God, with that mysterious gift of Life in Himself,[265] has within Him a perpetual spring of rejuvenescence for a faded and dying world. A renewal of hearts is in process during all the days of time, a passage for soul after soul out of death into life.[266] The third scene is the general Resurrection and general Judgment.[267] The first was the resurrection of comparatively few; the second is the resurrection of many; the third will be the resurrection of all. If it is said that the believer "cometh not into judgment," the word in that place plainly signifies condemnation.[268]

Clear and plain above all such subtleties ring out the awe-inspiring words: "it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the Judgment;" "we must all appear before the judgment-seat of Christ."[269]

Reason supplies us with two great arguments for the General Judgment. One from the conscience of history, so to speak; the other from the individual conscience.

1. General history points to a general judgment. If there is no such judgment to come, then there is no one definite moral purpose in human society. Progress would be a melancholy word, a deceptive appearance, a stream that has no issue, a road that leads nowhere. No one who believes that there is a Personal God, Who guides the course of human affairs, can come to the conclusion that the generations of man are to go on for ever without a winding-up, which shall decide upon the doings of all who take part in human life. In the philosophy of nature, the affirmation or denial of purpose is the affirmation or denial of God. So in the philosophy of history. Society without the General Judgment would be a chaos of random facts, a thing without rational retrospect or definite end —i. e., without God. If man is under the government of God, human history is a drama, long-drawn, and of infinite variety, with inconceivably numerous actors. But a drama must have a last act. The last act of the drama of history is "The Day of the Judgment."

2. The other argument is derived from the individual conscience.

Conscience, as a matter of fact, has two voices. One is imperative; it tells us what we are to do. One is prophetic, and warns us of something which we are to receive. If there is to be no Day of the General Judgment, then the million prophecies of conscience will be belied, and our nature prove to be mendacious to its very roots.

There is no essential article of the Christian creed like this which can be isolated from the rest, and treated as if it stood alone. There is a solidarity of each with all the rest. Any which is isolated is in danger itself, and leaves the others exposed. For they have an internal harmony and congruity. They do not form a hotchpot of credenda. They are not so many beliefs but one belief. Thus the isolation of articles is perilous. For, when we try to grasp and to defend one of them, we have no means left of measuring it but by terms of comparison which are drawn from ourselves, which must therefore be finite, and by the inadequacy of the scale which they present, appear to render the article of faith thus detached incredible. Moreover, each article of our creed is a revelation of the Divine attributes, which meet together in unity. To divide the attributes by dividing the form in which they are revealed to us is to belie and falsify the attribute; to give a monstrous development to one by not taking into account some other which is its balance and compensation. Thus, many men deny the truth of a punishment which involves final separation from God. They glory in the legal judgment which "dismisses hell with costs." But they do so by fixing their attention exclusively upon the one dogma which reveals one attribute of God. They isolate it from the Fall, from the Redemption by Christ, from the gravity of sin, from the truth that all whom the message of the Gospel reaches may avoid the penal consequences of sin. It is impossible to face the dogma of eternal separation from God without facing the dogma of Redemption. For Redemption involves in its very idea the intensity of sin, which needed the sacrifice of the Son of God; and further, the fact that the offer of salvation is so free and wide that it cannot be put away without a terrible wilfulness.

In dealing with many of the articles of the creed, there are opposite extremes. Exaggeration leads to a revenge upon them which is, perhaps, more perilous than neglect. Thus, as regards eternal punishment, in one country ghastly exaggerations were prevalent. It was assumed that the vast majority of mankind "are destined to everlasting punishment"; that "the floor of hell is crawled over by hosts of babies a span long." The inconsistency of such views with the love of God, and with the best instincts of man, was victoriously and passionately demonstrated. Then unbelief turned upon the dogma itself, and argued, with wide acceptance, that "with the overthrow of this conception goes the whole redemption-plan, the Incarnation, the Atonement, the Resurrection, and the grand climax of the Church-scheme, the General Judgment." But the alleged article of faith was simply an exaggeration of that faith, and the objections lay altogether against the exaggeration of it.

IIWe have now to speak of the removal of that terror which accompanies the conception of the Day of the Judgment, and of the sole means of that emancipation which St. John recognises. For terror there is in every point of the repeated descriptions of Scripture – in the surroundings, in the summons, in the tribunal, in the trial, in one of the two sentences.

"God is love," writes St. John, "and he that abideth in love abideth in God: and God abideth in him. In this [abiding], love stands perfected with us,[270] and the object is nothing less than this," not that we may be exempted from judgment, but that "we may have boldness in the Day of the Judgment." Boldness! It is the splendid word which denotes the citizen's right of free speech, the masculine privilege of courageous liberty.[271] It is the tender word which expresses the child's unhesitating confidence, in "saying all out" to the parent. The ground of the boldness is conformity to Christ. Because "as He is," with that vivid idealizing sense, frequent in St. John when he uses it of our Lord – "as He is," delineated in the fourth Gospel, seen by "the eye of the heart"[272] with constant reverence in the soul, with adoring wonder in heaven, perfectly true, pure, and righteous – "even so" (not, of course, with any equality in degree to that consummate ideal, but with a likeness ever growing, an aspiration ever advancing[273]) – "so are we in this world," purifying ourselves as He is pure.