полная версия

полная версияRuins of Ancient Cities (Vol. 2 of 2)

St. Paul, in his way from Corinth to Jerusalem, passed through Miletus; and as he went by sea, and would not take Ephesus in his way, he caused the priests and bishops of the church of Ephesus to come to Miletus11.

Miletus fell under subjection to the Romans, and became a considerable place under the Greek emperors. Then it fell under the scourge of the Turks; one of the sultans of which (A. D. 1175) sent twenty thousand men, with orders to lay waste the Roman imperial provinces, and bring him sand, water, and an oar. All the cities on the Mæander were then ruined: since which, little of the history of Miletus has been known.

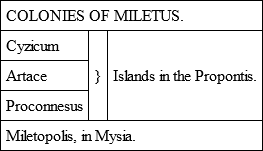

The Milesians early applied themselves to navigation; in the spirit of which they, in the process of time, planted not less than eighty colonies, in different parts of the world; and as we are ourselves so largely engaged in colonisation, perhaps an account of the colonies, sent out by the Milesians, may not be deemed uninteresting.

From this list we may imagine to what a height of power and civilisation this city must have once attained. Babylon stands in a wilderness and a desert by its side.

Miletus was adorned with superb edifices; and was greatly celebrated for its trade, sciences, and arts. It gave birth also to many eminent persons; amongst whom may be particularly mentioned, Thales12, Anaximenes13, Anaximander14, Hecatæus15, Timotheus16, also the celebrated Aspasia, the wife of Pericles. It was also famous for its excellent wool, with which were made stuffs and garments, held in the highest reputation both for softness, elegance, and beauty.

It had a temple dedicated to Apollo Didymæus, which was burnt by Xerxes. The Milesians, however, soon after rebuilt it, and upon so large a scale, that Strabo describes it as having been equal in extent to a village; so large indeed was it, that it could never be covered. It stood in a thick grove. With what magnificence and prodigious spirit this edifice was designed, may in some measure be collected from the present remains. Strabo called it the “greatest of all temples;” adding that it continued without a roof on account of its bigness; Pausanias mentions it as unfinished, but as one of the wonders peculiar to Ionia; and Vitruvius mentions this among the four temples, which have raised their architects to the summit of renown17.

There was a magnificent theatre also built of stone, but cased with marble, and greatly enriched with sculptures. There was also one temple of Venus in this town, and another in the neighbourhood.

Miletus is now called Palatskia (the palaces). Notwithstanding its title, and the splendour of its ancient condition, it is but a mean place now. The principal relic of its former magnificence is a ruined theatre, measuring in length four hundred and fifty-seven feet. The external face of this vast fabric is marble. The front has been removed. A few seats only remain, and those, as usual, ranged on the slope of a hill. The vaults which supported the extremities, with the arches or avenues of the two wings, are constructed with such solidity, that they will not easily be demolished. The entrance of the vault is nearly filled up with rubbish; but when Dr. Chandler crept into it, led by an Armenian, with a candle in a long paper lantern, innumerable bats began flitting about them; and the stench was intolerable.

The town was spread with rubbish and overgrown with thickets. The vestiges of “the heathen city,” are pieces of wall, broken arches, and a few scattered pedestals and inscriptions, a square marble urn, and many wells. One of the pedestals has belonged to a statue of the Emperor Hadrian, who was a friend to the Milesians, as appears from the titles of Saviour and Benefactor, bestowed upon him. Another has supported the Emperor Severus, and has a long inscription, with this preamble: “The senate and people of the city of the Milesians, the first settled in Ionia, and the mother of many and great cities both in Pontus and Egypt, and in various other parts of the world.” This lies among the bushes behind the theatre.

Several piers of an aqueduct are standing. Near the ferry is a large couchant lion, of white marble; and in a Turkish burying-ground another; and traces remain of an old fortress. Besides these, there are a considerable number of forsaken mosques; and among the ruins are several fragments of ancient churches.

Wheler says, that in his time, there were many inscriptions, most of them defaced by time and weather; some upon single stones, others upon very large tombs. On one of them were carved two women hunting, with three dogs; the foremost holding a hare in its mouth.

“Miletus,” says Dr. Chandler, from whom we have borrowed several passages in this article, “was once powerful and illustrious. The early navigators extended its commerce to remote regions; the whole Euxine Sea, the Propontis, Egypt, and other countries, were frequented by its ships, and settled by its colonies. It withstood Darius, and refused to admit Alexander. It has been styled the metropolis and head of Ionia; the bulwark of Asia; chief in war and peace; mighty by sea; the fertile mother, which had poured forth her sons to every quarter. It afterwards fell so low as to furnish a proverbial saying, ‘The Milesians were once great;’ but if we compare its ancient glory, and its subsequent humiliation, with its present state, we may justly exclaim, ‘Miletus, how much lower art thou now fallen18!’”

NO. IV. – NAUPLIA

This town, now called Napoli di Romania, is situated along the foot of the rocky promontory, which projects into the sea, at the head of the gulf of Napoli. Its walls were built by the Venetians.

Ancient Nauplia, which is said to have been built by Nauplius, absurdly called the son of Neptune, became the chief naval arsenal of the Argives. Even so early as the time of Pausanias, however, it had become desolate; only a few remains of a temple, and of the walls, then existing. Its modern history is rather interesting.

The Venetians obtained possession in 1460. In 1495 it surrendered to Bajazet, but was again taken by the Venetians, under Morozini, in 1586, after a month’s siege, and became the head-quarters of that nation, in the Morea. In 1714, it was treacherously given up to Ali Coumourgi, and was the seat of Turkish government, and residence of the Pasha of the Morea; till Tripolizzi was selected as being more central; when it became subject to the Bey of Argos. The crescent remained uninterruptedly flying on this fortress, till the 12th of December 1822, when it surrendered to the Greeks, after a long and tedious blockade; the Turkish garrison having been reduced to such a state of starvation, as to feed on the corpses of their companions. In 1825, Ibrahim Pasha made a fruitless attempt to surprise the place; and it has been the strong-hold of the Greeks in their struggle for liberty. In April, 1826, the commission of government held their sittings here; but were obliged to retire to Ægina, on account of civil dissentions, and two of the revolted chiefs being in possession of the Palamadi. During the presidency of Capo d’Istrias, who always resided, and was assassinated in the town, it again became the seat of government; and on the 31st of January, 1833, Otho, Prince of Bavaria, arrived here, as first king of restored Greece.

The strength of Napoli is the citadel, which is called the Palamadi, over whose turreted walls a few cypresses raise their sombre heads. It stands on the easternmost and highest elevation of the promontory, and completely overhangs and commands the town. To all appearance it is impregnable, and, from its situation and aspect, has been termed the Gibraltar of Greece. It is seven hundred and twenty feet above the sea; and has only one assailable point, where a narrow isthmus connects it with the main land; and this is overlooked by a rocky precipice.

Mr. Dodwell made fruitless inquiries in respect to the caves and labyrinths near Nauplia, which are said to have been formed by the Cyclops; but a minute examination is neither a safe nor easy undertaking. “The remains that are yet unknown,” says he, “will be brought to light, when the reciprocal jealousy of the European powers permits the Greeks to break their chains,19 and to chase from their outraged territory that host of dull oppressors, who have spread the shades of ignorance over the land that was once illuminated by science, and who unconsciously trample on the venerable dust of the Pelopidæ and the Atridæ.”

Nauplia is a miserable village; the houses have nothing peculiar about them, but are built in the common form of the lowest habitations of the villages of France and Savoy. The inhabitants are indolent. “The indolence of the Napolitans,” says M. La Martine, “is mild, serene, and gay – the carelessness of happiness; while that of the Greek is heavy, morose, and sombre; it is a vice, which punishes itself.”20

NO. V. – NEMEA

A town of Argolis, greatly distinguished by the games once celebrated there. These games (called the Nemean games) were originally instituted by the Argives in honour of Archemorus, who died from the bite of a serpent; and, afterwards, renewed in honour of Hercules, who in that neighbourhood is said to have destroyed a lion by squeezing him to death.

These games consisted of foot and horse races, and chariot races; boxing, wrestling, and contests of every kind, both gymnastic and equestrian. They were celebrated on the 12th of our August, on the 1st and 3rd of every Olympiad; and continued long after those of Olympia were abolished.

In the neighbouring mountains is still shown the den of the lion, said to have been slain by Hercules; near which stand the remains of a considerable temple, dedicated to Jupiter Nemeus and Cleomenes, formerly surrounded by a grove of cypresses.

Of this temple three columns only are remaining. These columns, two of which belonging to the space between antæ, support their architrave. These columns are four feet six inches and a half in diameter, and thirty-one feet ten inches and a half in height, exclusive of the capitals. The single column is five feet three inches diameter, and belongs to the peristyle. The temple was hexastyle and peripteral, and is supposed to have had fourteen columns on the sides. The general intercolumniation is seven feet and a half, and those at the angles five feet eleven inches and a quarter. It stands upon three steps, each of which is one foot two inches in height. The capital of the exterior column has been shaken out of its place, and will probably ere long fall to the ground. “I have not seen in Greece,” continues Mr. Dodwell, “any Doric temple, the columns of which are of such slender proportions as those of Nemea. The epistylia are thin and meagre, and the capitals too small for the height of the columns. It is constructed of a soft calcareous stone, which is an aggregate of sand and small petrified shells, and the columns are coated with a fine stucco. Pausanias praises the beauty of the temple; but, even in his time, the roof had fallen, and not a single statue was left.”

No fragments of marble are found amongst the ruins, but an excavation would probably be well repaid, as the temple was evidently thrown down at one moment, and if it contained any sculptured marbles, they are still concealed by the ruins.

Near the temple are several blocks of stones, some fluted Doric frusta, and a capital of small dimensions. This is supposed to have formed part of the sepulchre of Archemorus. Mr. Dodwell, however, found no traces of the tumulus of Lycurgus, his father, king of Nemea, mentioned by Pausanias, nor any traces of the theatre and stadium.

Beyond the temple is a remarkable summit, the top of which is flat, and visible in the gulf of Corinth. On one side is a ruinous church, with some rubbish; perhaps where Osspaltes and his father are said to have been buried. Near it is a very large fig-tree. To this a goatherd repaired daily before noon with his flock, which huddled together in the shade until the extreme heat was over, and then proceeded orderly to feed in the cool upon the mountain.

“Nemea,” continues Mr. Dodwell, “is more characterised by gloom than most of the places I have seen. The splendour of religious pomp, and the long animation of gymnastic and equestrian exercises, have been succeeded by the dreary vacancy of a death-like solitude. We saw no living creatures but a ploughman and his oxen, in a spot which was once exhilarated by the gaiety of thousands, and resounded with the shouts of a crowded population21.”

NO. VI. – NINEVEH

Of Nineveh, the mighty city of old,

How like a star she fell and pass’d away!

Atherstone.The Assyrian empire was founded by Ashur, the son of Shem, according to some writers; but according to others, by Nimrod; and to others, by Ninus.

Ninus, according to Diodorus Siculus, is to be esteemed the most ancient of the Assyrian kings. Being of a warlike disposition, and ambitious of that glory which results from courage, says he, he armed a considerable number of young men, that were brave and vigorous like himself; trained them up in laborious exercises and hardships, and by that means accustomed them to bear the fatigues of war patiently, and to face dangers with intrepidity. What Diodorus states of Ninus, however, is much more applicable to his father, Nimrod, the son of Cush, grandson of Cham, and great-grandson of Noah; he who is signalised in scripture as having been “a mighty hunter before the Lord;” a distinction which he gained from having delivered Assyria from the fury and dread of wild animals; and from having, also, by this exercise of hunting, trained up his followers to the use of arms, that he might make use of them for other purposes more serious and extensive.

The next king of Assyria was Ninus, the son of Nimrod. This prince prepared a large army, and in the course of seventeen years conquered a vast extent of country; extending to Egypt on one side, and to India and Bactriana on the other. On his return he resolved on building the largest and noblest city in the world; so extensive and magnificent, as to leave it in the power of none, that should come after him, to build such another. It is probable, however, that Nimrod laid the foundations of this city, and that Ninus completed it: for the ancient writers often gave the name of founder to persons, who were only entitled to the appellation of restorer or improver.

This city was called Nineveh. Its form and extent are thus related by Diodorus, who states that he took his account from Ctesias the Gnidian: – “It was of a long form; for on both sides it ran out about twenty-three miles. The two lesser angles, however, were only ninety furlongs a-piece; so that the circumference of the whole was about seventy-four miles. The walls were one hundred feet in height; and so broad, that three chariots might be driven together upon it abreast; and on these walls were fifteen hundred turrets, each of which was two hundred feet high.”

When the improver had finished the city, he appointed it to be inhabited by the richest Assyrians; but gave leave, at the same time, to people of other nations (as many as would) to dwell there; and, moreover, allowed to the citizens at large a considerable territory next adjoining them.

Having finished the city, Ninus marched into Bactria; his army consisting of one million seven hundred thousand men, two hundred thousand horse, and sixteen thousand chariots armed with scythes. This number is, doubtless, greatly exaggerated. With so large a force, he could do no otherwise than conquer a great number of cities. But having, at last, laid siege to Bactria, the capital of the country, it is said that he would probably have failed in his enterprise against that city, had he not been assisted by the counsel of Semiramis, wife to one of his officers, who directed him in what manner to attack the citadel. By her means he entered the city, and becoming entire master of it, he got possession of an immense treasure. He soon after married Semiramis; her husband having destroyed himself, to prevent the effects of some threats that Ninus had thrown out against him. By Semiramis, Ninus had one son, whom he named Ninyas; and dying not long after, Semiramis became queen: who, to honour his memory, erected a magnificent monument, which is said to have remained a long time after the destruction of the city.

The history of this queen is so well known,22 that we shall not enlarge upon it; we having already done so in our account of Babylon; for she was one of the enlargers of that mighty city.

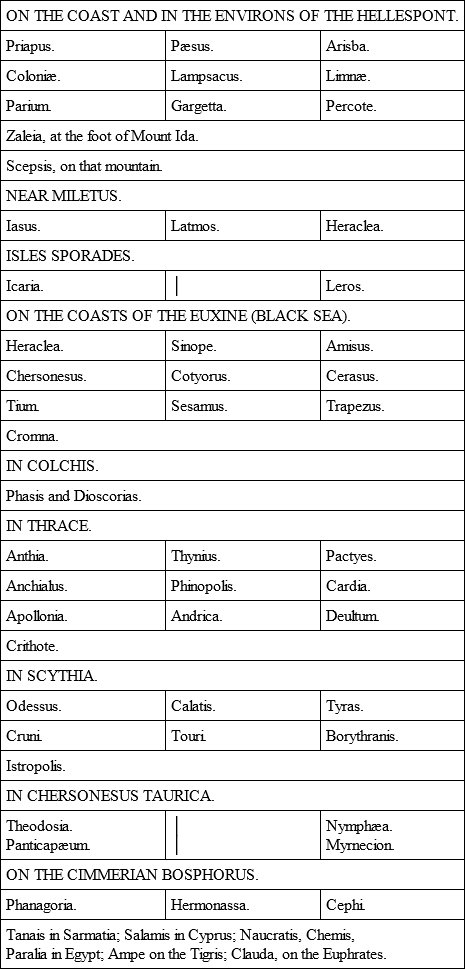

There is a very great difference of opinion, in regard to the time in which Semiramis lived. According to

Alexander’s opinion of this celebrated woman may be gathered from the following passage of his speech to his army: – “You wish to enjoy me long; and even, if it were possible, for ever; but, as to myself, I compute the length of my existence, not by years, but by glory. I might have confined my ambition within the narrow limits of Macedonia; and, contented with the kingdom my ancestors left me, have waited, in the midst of pleasures and indolence, an inglorious old age. I own that if my victories, not my years, are computed, I shall seem to have lived long; but can you imagine, that after having made Europe and Asia but one empire, after having conquered the two noblest parts of the world, in the tenth year of my reign and the thirtieth of my age, that it will become me to stop in the midst of so exalted a career, and discontinue the pursuit of glory to which I have entirely devoted myself? Know, that this glory ennobles all things, and gives a true and solid grandeur to whatever appears insignificant. In what place soever I may fight, I shall fancy myself upon the stage of the world, and in presence of all mankind. I confess that I have achieved mighty things hitherto; but the country we are now in reproaches me that a woman has done still greater. It is Semiramis I mean. How many nations did she conquer! How many cities were built by her! What magnificent and stupendous works did she finish! How shameful is it, that I should not yet have attained to so high a pitch of glory! Do but second my ardour, and I will soon surpass her. Defend me only from secret cabals and domestic treasons, by which most princes lose their lives; I take the rest upon myself, and will be answerable to you for all the events of the war.”

“This speech,” says Rollin, “gives us a perfect idea of Alexander’s character. He had no notion of true glory. He did not know either the principle, the rule, or end of it. He certainly placed it where it was not. He was strongly prejudiced in vulgar error, and cherished it. He fancied himself born merely for glory; and that none could be acquired but by unbounded, unjust, and irregular conduct. In his impetuous sallies after a mistaken glory, he followed neither reason, virtue, nor humanity; and as if his ambitious caprice ought to have been a rule and standard to all other men, he was surprised that neither his officers nor soldiers would enter into his views, and that they lent themselves very unwillingly to support his ridiculous enterprises.” These remarks are well worthy the distinguished historian who makes them.

Semiramis was succeeded by her son Ninyas; a weak and effeminate prince, who shut himself up in the city, and, seldom engaging in affairs, naturally became an object of contempt to all the inhabitants. His successors are said to have followed his example; and some of them even went beyond him in luxury and indolence. Of their history no trace remains.

At length we come to Pull, supposed to be the father of Sardanapalus; in whose reign Jonah is believed to have lived. “The word of the Lord,” says the Hebrew scripture, “came unto Jonah, the son of Amittai, saying, Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness is come up before me.” Jonah, instead of acting as he was commanded, went to Joppa, and thence to Tarshish. He was overtaken by a storm, swallowed by a whale, and thrown up again. Being commanded again, he arose and went to Nineveh, “an exceedingly great city of three days’ journey;” where, having warned the inhabitants, that in forty days their city should be overthrown, the people put on sackcloth, “from the greatest of them even to the least.” The king sat in ashes, and proclaimed a fast. “Let neither man nor beast,” said the edict, “herd nor flock, taste any thing; let them not feed, nor drink water; but let man and beast be covered with sackcloth; and cry mightily unto God; yea, let them turn every one from his evil way, and from the violence that is in their hands. Who can tell if God will turn and repent, and turn away from his fierce anger, that we perish not?”

On the king’s issuing this edict, the people did as they were commanded, and the ruin was delayed. On finding this, the prophet acted in a very unworthy manner. To have failed as a prophet gave him great concern; insomuch, that he desired death. “Take, I beseech thee, O Lord, my life from me; for it is better for me to die than to live.” “Shall I not spare Nineveh,” answered the Lord, “that great city, wherein are more than six-score thousand persons, that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle?”

Sardanapalus was, beyond all other sovereigns recorded in history, the most effeminate and voluptuous; the most perfect specimen of sloth, luxury, cowardice, crime, and elaborate folly, that was, perhaps, ever before exhibited to the detestation of mankind. He clothed himself in women’s attire, and spun fine wool and purple amongst throngs of concubines. He painted likewise his face, and decked his whole body with other allurements. He imitated, also, a woman’s voice; and in a thousand respects disgraced his nature by the most unbounded licentiousness and depravity. He even wished to immortalise his impurities; selecting for his epitaph the following lines: —

Hæc habeo quæ edi, quæque exsaturata libidoHausit; at illa jacent multa et præclara relicta.“This epitaph,” says Aristotle, “is only fit for a hog.”23

Through all the city sounds the voice of joy,And tipsy merriment. On the spacious walls,That, like huge sea-cliffs, gird the city in,Myriads of wanton feet go to and fro;Gay garments rustle in the scented breeze;Crimson and azure, purple, green, and gold;Laugh, jest, and passing whisper are heard there;Timbrel and lute, and dulcimer and song;And many feet that tread the dance are seen,And arms unflung, and swaying head-plumes crown’d:So is that city steep’d in revelry24.In this dishonourable state Sardanapalus lived several years. At length the governor of Media, having gained admittance into his palace, and seen with his own eyes a king guilty of such criminal excesses; enraged at the spectacle, and not able to endure that so many brave men should be subject to a prince more soft and effeminate than the women themselves, immediately resolved to put an end to his dominion. He therefore formed a conspiracy against him; and in this he was joined by Belesis, governor of Babylon, and several others. Supporting each other for the same end, the one stirred up the Medes and Persians; the other inflamed the inhabitants of

Babylon. They gained over, also, the king of Arabia. Several battles, however, were fought, in all of which the rebels were repulsed and defeated. They became, therefore, so greatly disheartened, that at length the commanders resolved every one to return to their respective countries; and they had done so, had not Belesis entertained great faith in an astrological prediction. He was continually consulting the stars; and at length solemnly assured the confederated troops, that in five days they would be aided by a support, they were at present unable to imagine or anticipate; – the gods having given to him a decided intimation of so desirable an interference. Just as he had predicted, so it happened; for before the time he mentioned had expired, news came that the Bactrians, breaking the fetters of servitude, had sprung into the field, and were hastening to their assistance.