полная версия

полная версияThrough Finland in Carts

It was a charming picture, one well worth retaining on the retina of memory.

It was the last day; the Karjalan wedding was over, and all the choirs, numbering altogether nearly a thousand voices, sang chants and hymns most beautifully, their combined voices being heard far through the woods and across the lakes.

It was really a grand spectacle, those thousand men and women on the platform, comprising peasants, farmers, students, professors, all brought together merely to sing, while below and on the opposite hill three thousand seats were filled by a mixed audience, behind whom again, among the pine-trees, sat several thousand more. As a final effort the conductor called upon every one to join in the National Anthem. Up rose ten thousand or twelve thousand persons, and, as one man, they sang their patriotic verses beneath the blue canopy of heaven. It was wonderful; to a stranger the harmony of the whole was amazing; indeed, so successful did it prove, that national song after national song was sung by that musical audience. We looked on and marvelled. Music attracts in Finland, for from end to end of the land the people are imbued with its spirit and feel its power.

The sun blazed, the pine cones scented the air, the birds sang, and we felt transported back to old Druidical days when people met in the open for song and prayer. It was all very simple, but very delightful, and the people seemed to most thoroughly enjoy hearing their national airs; the whole scene again reminded us of Ober Ammergau, or of a Highland out-of-door Communion Service.

Alas! the Finnish national dress has almost disappeared, but at the Sordavala Festival a great attempt was made to revive it at the enormous open-air concerts in the public park, where some of the girls, lying or sitting under the pine-trees on the hill opposite listening to the choir singing, wore the dress of Suomi.

The national colours are red and yellow, or white and bright blue, and much dispute arises as to which is really right, for while the heraldry book says red and yellow, the country folk maintain blue and white. White loose blouses of fine Finnish flannel seemed most in favour, with a short full underskirt of the same material; geometrical embroidery about two inches wide in all colours and patterns being put round the hem of the short dress as well as brace fashion over the bodice; in some cases a very vivid shade of green, a sort of pinafore bodice with a large apron of the same colour falling in front, was noticeable; the embroidery in claret and dark green running round all the border lines; at the neck this embroidery was put on more thickly, and also at the waist belt. Round the apron hung a deep and handsome fringe; altogether the dress with its striking colours and tin or silver hangings was very pleasing. Unfortunately the girls seemed to think that even when they wore their national dress they ought to wear also a hat and gloves; although even the simplest hat spoils the effect.

At the back of the wood, where we wandered for a little shade and quiet rest, we found our dear friends the "Runo singers." The name originated from the ancient songs having been written down on sticks, the Runo writing being cut or burnt in, this was the bards' only form of music. Now these strange musical memoranda can only be found in museums. Our Runo singers, delighted with the success of the marriage-play they had coached, welcomed us warmly, and at once rose to shake hands as we paused to listen to their kantele playing and quaint chanting.

It may be well to mention that the Finnish language is very remarkable. Like Gaelic, it is musical, soft and dulcet, expressive and poetical, comes from a very old root, and is, in fact, one of the most interesting languages we possess. But some of the Finnish words are extremely long, in which respect they excel even the German. As a specimen of what a Finnish word can be, we may give Oppimattomuudessansakin, meaning, "Even in his ignorance."

The language is intensely difficult to learn, for it has sixteen cases, a fact sufficient to appal the stoutest heart. However, there is one good thing about Finnish, namely, that it is spoken absolutely phonetically, emphasis being invariably laid on the first syllable. For instance, the above word is pronounced (the "i" being spoken as "e") Oppi-ma-tto-muu-des-san-sa-kin.

Finnish possesses a you and a thou, which fact, though it cannot lighten the difficulties, does away with the terrible third person invariably in use in Swedish, where people say calmly:

"Has the Herr Professor enjoyed his breakfast?"

"Yes, thanks, and I hope the Mrs. Authoress has done the same."

By the Swedish-speaking Finns it is considered the worst of ill-breeding for a younger person to address an elder as "you," or for strangers to speak to one another except in the manner above indicated.

Finnish is one of the softest of tongues, and of all European languages most closely resembles the Magyar or Hungarian. Both of these come from the Ugrian stock of Agglutinative languages, and therefore they always stick to the roots of the word and make grammatical changes by suffixes. Vowels are employed so incessantly that the words are round and soft, and lend themselves easily to song. There are only twenty-two letters in the Finnish alphabet, and as F is very seldom employed, even that number is decreased. The use of vowels is endless; the dotted ö, equivalent to the French eu, being often followed by an e or i, and thereby rendered doubly soft.

Finns freely employ thou and thee, and add to these forms of endearment numerous suffixes. Human names, all animals, plants, metals, stones, trees – anything, in fact – can be used in the diminutive form.

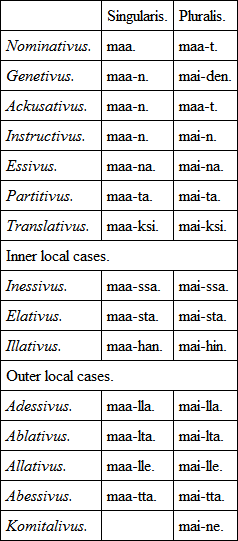

Finnish is almost as difficult to learn as Chinese. Every noun has sixteen cases, and the suffixes alter so much, one hardly recognises the more complicated as the outcome of the original nominative. It takes, therefore, almost a lifetime to learn Finnish thoroughly, although the structure of their sentences is simple, and, being a nation little given to gush, adverbs and adjectives are seldom used.

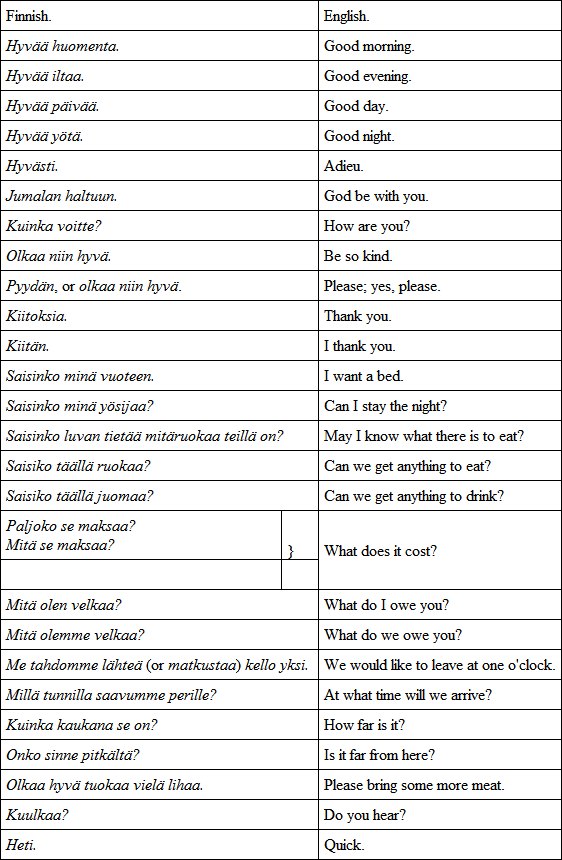

As an example of Finnish, we give the following table made out at our request, so that we might learn a few sentences likely to prove useful when travelling in the less-frequented parts of the country – every letter is pronounced as written.

The foregoing are all in the objective case; in the nominative they would be: —

Liha, Maito, Leipä, Voi, Kahvi, Sokeri, Kala, Muna, Olut.

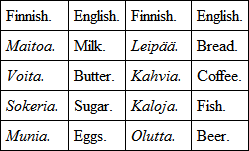

The numeration table is as follows: —

To show the difficulties of the declensions, we take, as an example, the ordinary word land.

Declensions of the word Maa=Land.

Is such a declension not enough to strike terror to the stoutest heart?

But now to return to the Kalevala itself, which is said to be one of the grandest epic poems in existence. The word Kalevala means "Land of heroes," and it is undoubtedly a poem of nature-worship. It points to a contest between Light and Darkness, Good and Evil, and in this case the Light and Good are represented by the Finns, the Darkness and Evil by the Laps. Although it is a poem of nature-worship, full of most wonderful descriptions – some of the lines in praise of the moon and sun, the sea and water-ways, the rivers and hills, and the wondrous pine forests of Finland, are full of marvellous charm – it also tells the story of love, and many touching scenes are represented in its verses.

"It is unlike other epics," says Edward Clodd, "in the absence of any apotheosis of clique or clan or dynasty, and in the theatre of action being in no ideal world where the gods sit lonely on Olympus, apart from men. Its songs have a common author, the whole Finnish people; the light of common day, more than that of the supernatural, illumines them."

Before going further, it may be well to mention how the Kalevala came into existence. Finland is thinly peopled, but every Finn is at heart musical and poetical; therefore, far removed from the civilised world, they made songs among themselves – fantastic descriptions of their own country. By word of mouth these poems were handed on from generation to generation, and generally sung to the accompaniment of the kantele in a weird sort of chant. By such means the wonderful Sagas of Iceland were preserved to us until the year 1270, when they first began to be written down on sheepskins, in Runic writing, for Iceland at that date shone as a glorious literary light when all was gloom around. By means of tales, and poems, and chanted songs, the Arabian Nights stories, so dearly loved by the Arabs, which as yet have not been collected as they should have been, are related even to-day by the professional story-tellers we have seen in the market-places of Morocco.

Professor Elias Lönnrot, as mentioned in the last chapter, realising the value to scholars and antiquaries of the wonderful poems of Finland, so descriptive of the manners and customs of the Finns, set to work in the middle of the nineteenth century to collect and bring them out in book form before they were totally forgotten. This was a tremendous undertaking; he travelled through the wildest parts of Finland; disguised as a peasant, he walked from village to village, from homestead to homestead, living the life of the people, and collecting, bit by bit, the poems of his country. As in all mythological or gipsy tales, he found many versions of the same subject, for naturally verses handed on orally change a little in different districts from generation to generation. But he was not to be beaten by this extra amount of work, and finally wove into a connected whole the substance of the wondrous tales he had heard from the peasantry. This whole he called Kalevala, the name of the district where the heroes of the poem once existed. Gramophones will in future collect such treasures for posterity.

In 1835 the first edition appeared. It contained thirty-two runos or cantos of about twelve thousand lines, and the second, which was published in 1849, contained fifty runos or about twenty-two thousand eight hundred lines (seven thousand more than the Iliad).

There is no doubt about it, experts declare, that the poems or verses were written at different times, but it is nearly all of pre-Christian origin, for, with the exception of a few prayers in the last pages, there are few signs of Christian influence.

No one knows exactly how these poems originated. Indeed, the Kalevala is unique among epics, although distinct traces of foreign influence may occasionally be found, the Christian influence being only noticeable in the last runos when the Virgin's Son, the Child Christ, appears, after which advent Wäinämöinen disappears for unknown lands. With this exception the entire poem is of much earlier date.

The last runo is truly remarkable.

"Mariatta, child of beauty," becomes wedded to a berry —

Like a cranberry in feature,Like a strawberry in flavour.…Wedded to the mountain berry…Wedded only to his honour.…I shall bear a noble hero,I shall bear a son immortal,Who will rule among the mighty,Rule the ancient Wäinämöinen.…In the stable is a manger,Fitting birth-place for the hero.…Thereupon the horse, in pity,Breathed the moisture of his nostrils,On the body of the Virgin,Wrapped her in a cloud of vapour,Gave her warmth and needed comforts,Gave his aid to the afflictedTo the virgin Mariatta.There the babe was born and cradled,Cradled in a woodland manger.This shows Christian origin!

Wäinämöinen's place is gradually usurped by the "Wonder-babe," and the former departs in this stanza —

Thus the ancient Wäinämöinen,In his copper-banded vesselLeft his tribe in Kalevala,Sailing o'er the rolling billows,Sailing through the azure vapours,Sailing through the dusk of evening,Sailing to the fiery sunset,To the higher landed regions,To the lower verge of heaven;Quickly gained the far horizon,Gained the purple-coloured harbour,There his bark he firmly anchored,Rested in his boat of copper;But he left his harp of magic,Left his songs and wisdom sayingsTo the lasting joy of Suomi.Thus old Wäinämöinen sails away into unfathomable depths.

The Kalevala has, up to the present time, been a much-neglected poem, but there is now an excellent English translation by Martin Crawford, an American by birth, from which we have taken the liberty of quoting. Mr. Andrew Lang has charmingly discoursed on the great national poem of the Finns, and Mr. Edward Clodd, who wrote a delightful series of articles in Knowledge on the same subject, has kindly placed his notes in my hands.

There is no doubt about it that the fantastic mythology of the Finns has not received as much attention as it deserves. "Although mythology and theology are one," says Mr. Clodd, "we find among the ancient Finns the worship of natural objects, all living things being credited with life, and all their relations being regarded as the actions of the mighty powers."

Naturally in a country so undisturbed and isolated as Finland, fantastic mythology took firm root, and we certainly find the most romantic and weird verses in connection with the chief heroes of the Kalevala, namely, Wäinämöinen and Ilmarinen, who broadly resemble the Norse demigods Odin and Thor.

After any one has been to Finland, he reads the Kalevala with amazement. What pen could describe more faithfully the ways of the people? Every line is pregnant with life. Their food, their clothing, their manners and customs, their thoughts and characteristics are all vividly drawn, as they were hundreds of years ago, and as they remain to-day.

When we peep into the mysteries of the Kalevala and see how trees are sacred, how animals are mythological, as, for instance, in the forty-sixth rune, which speaks of the bear who "was born in lands between sun and moon, and died not by man's deeds, but by his own will," we understand the Finnish people. Indeed the wolf, the horse, the duck, and all animals find their place in this wondrous Kalevala; and dream stories are woven round each creature till the whole life of Finland has become impregnated by a fantastic sort of romance.

The Kalevala opens with a creation myth of the earth, sea, and sky from an egg, but instead of the heroes living in some supernatural home of their own, they come down from heaven, distribute gifts among men, and work their wonders by aid of magic, at the same time living with the people, and entering into their daily toils.

It is strange that the self-developing egg should occur in the Kalevala of Northern Europe, for it also appears among the Hindoos and other Eastern peoples, pointing, maybe, to the Mongolian origin of the Finnish people.

The way the life of the people is depicted seems simply marvellous, and the description holds good even at the present time. For instance, these lines taken at hazard speak of spinning, etc. —

Many beauteous things the maiden,With the spindle has accomplished,Spun and woven with her fingers;Dresses of the finest textureShe in winter has upfolded,Bleached them in the days of spring-time,Dried them at the hour of noonday,For our couches finest linen,For our heads the softest pillows,For our comfort woollen blankets.Or, again, speaking of the bride's home, it likens the father-in-law to her father, and describes the way they all live together in Finland even to-day, and bids her accept the new family as her own —

Learn to labour with thy kindred;Good the home for thee to dwell in,Good enough for bride and daughter.At thy hand will rest the milk-pail,And the churn awaits thine order;It is well here for the maiden,Happy will the young bride labour,Easy are the resting branches;Here the host is like thy father,Like thy mother is the hostess,All the sons are like thy brothers,Like thy sisters are the daughters.Here is another touch – the shoes made from the plaited birch bark, so commonly in use even at the present time; and, again, the bread made from bark in times of famine has ever been the Finnish peasant's food —

Even sing the lads of LaplandIn their straw-shoes filled with joyance,Drinking but a cup of water,Eating but the bitter tan bark.These my dear old father sang meWhen at work with knife or hatchet;These my tender mother taught meWhen she twirled the flying spindle,When a child upon the mattingBy her feet I rolled and tumbled.To-day, Finnish women still wash in the streams, and they beat their clothes upon the rocks just as they did hundreds, one might say thousands, of years ago and more – for the greater part of Kalevala was most undoubtedly written long before the Christian era in Finland.

Northlands fair and slender maidenWashing on the shore a head-dress,Beating on the rocks her garments,Rinsing there her silken raiment.In the following rune we find an excellent description of the land, and even a line showing that in those remote days trees were burned down to clear the land, the ashes remaining for manure – a common practice now.

Groves arose in varied beauty,Beautifully grew the forests,And again, the vines and flowers.Birds again sang in the tree-tops,Noisily the merry thrushes,And the cuckoos in the birch-trees;On the mountains grew the berries,Golden flowers in the meadows,And the herbs of many colours,Many lands of vegetation;But the barley is not growing.Osma's barley will not flourish,Not the barley of Wäinölä,If the soil be not made ready,If the forest be not levelled,And the branches burned to ashes.Only left the birch-tree standingFor the birds a place of resting,Where might sing the sweet-voiced cuckoo,Sacred bird in sacred branches.One could go on quoting passages from this strange epic – but suffice it to say that in the forty-sixth rune Wäinämöinen speaks to Otso, the bear —

Otso, thou my well beloved,Honey eater of the woodlands,Let not anger swell thy bosom.Otso was not born a beggar,Was not born among the rushes,Was not cradled in a manger;Honey-paw was born in etherIn the regions of the Moonland.With the chains of gold she bound itTo the pine-tree's topmost branches.There she rocked the thing of magic,Rocked to life the tender baby,'Mid the blossoms of the pine-tree,On the fir-top set with needles;Thus the young bear well was nurtured.Sacred Otso grew and flourished,Quickly grew with graceful movements,Short of feet, with crooked ankles,Wide of mouth and broad of forehead,Short his nose, his fur robe velvet;But his claws were not well fashioned,Neither were his teeth implanted.Swore the bear a sacred promiseThat he would not harm the worthy,Never do a deed of evil.Then Mielikki, woodland hostess,Wisest maid of Tapiola,Sought for teeth and claws to give him,From the stoutest mountain-ashes,From the juniper and oak-tree,From the dry knots of the alder.Teeth and claws of these were worthless,Would not render goodly service.Grew a fir-tree on the mountain,Grew a stately pine in Northland,And the fir had silver branches,Bearing golden cones abundant;These the sylvan maiden gathered,Teeth and claws of these she fashioned,In the jaws and feet of OtsoSet them for the best of uses.Taught him how to walk a hero.He freely gave his life to others.These are only a few stanzas taken haphazard from Kalevala, but they give some idea of its power.

At the Festival we met, among the Runo performers, a delightful woman. About forty, fat and broad, she had a cheerful countenance and kindly eyes, and she sang – if such dirges could be called singing – old Finnish songs, all of which seemingly lacked an end. She was absolutely charming, however, perfectly natural and unaffected, and when we got her in a corner, away from the audience, proved even more captivating than before the public.

First she sang a cradle song, and, as she moaned out the strange music, she patted her foot up and down and swayed her body to and fro, as though she were nursing a baby. She was simply frank too, and when asked to sing one particular song exclaimed —

"Oh yes, I can sing that beautifully; I sing it better than any one on the East Coast of Finland."

Abundant tears shed for no sufficient cause – for no cause at all, indeed – would seem to be a characteristic of these lady vocalists.

The singer of the bear legend wore a beautiful red-brocaded cap. In fact, her attire was altogether remarkable; her skirt, a pretty shade of purple shot with gold silk, was cut in such a way as to form a sort of corset bodice with braces across the shoulders, under which she wore a white chemisette. A beautiful, rich, red silk apron, and a set of well-chosen coloured scarves drawn across the breast completed her costume and added to the fantastic colouring and picturesqueness of the whole. She was very friendly; again and again she shook hands with us all in turn, and, during one of the most mournful of her songs, she sat so close to me that her elbow rested in my lap, while real tears coursed down her cheeks. It was quite touching to witness the true emotion of the woman; she rocked herself to and fro, and mopped her eyes with a neatly folded white cotton handkerchief, the while she seemed totally oblivious of our presence and enwrapped in her music. When she had finished she wiped away her tears, and then, as if suddenly recalled from another world, she appeared to realise the fact that we were present, and, overcome with grief, she apologised most abjectly for having forgotten herself so far as to cry before the strange ladies! This was no affectation; the woman was downrightly sorry, and it was not until we had patted her fondly and smiled our best thanks that she could be pacified at all and believe we were not offended.

In her calmer moments she drew, as we thought, a wonderful purse from under her apron – a cloth embroidered thing with beads upon it. Great was our surprise to discover that it contained snuff, from which she helped herself at intervals during the entertainment, never omitting to offer us some before she took her own pinch.

This unexpected generosity reminded us of an incident that occurred while crossing the Grosser Glockner mountain in the Tyrol, when we were overtaken by a violent snowstorm. Being above the snow line the cold and wind were intense. One of the guides, feeling sorry for us and evidently thinking we looked blue with cold, produced from his rucksack a large flask which contained his dearly loved schnapps. He unscrewed the cork and gravely offered it to us each in turn. There was no glass, nor did he even attempt to wipe the rim, although but an hour before we had seen all the guides drinking from the same bottle.

This equality of class is always to be found in lands where civilisation has not stepped in. "Each man is as good as his neighbour" is a motto in the remote parts of Finland, as it is in the Bavarian Highlands and other less-known parts. What the peasants have, they give freely; their goodness of heart and thoughtfulness are remarkable.

The Runo woman, who wept so unrestrainedly, had most beautiful teeth, and her smile added a particular charm to her face. When she was not singing she busied herself with spinning flax on the usual wooden oar, about five feet long and much carved and ornamented at one end. On the top, at the opposite end, was a small flat piece like another oar blade, only broader and shorter, fixed at such an angle that when she sat down upon it the carved piece stood up slant-wise beside her. Halfway up the blade some coloured cotton bands secured a bundle of flax, while in her hand she held a bobbin on to which she wove the thread.

She was never idle, for, when not occupied in singing to us, she spent her time spinning, always repeating, however, the second line of the other performers.