полная версия

полная версияWoman under socialism

Every day furnishes fresh proof of the rapid growth and spread of the ideas that we represent. On all fields there is tumult and push. The dawn of a fair day is drawing nigh with mighty stride. Let us then ever battle and strive forward, unconcerned as to "where" and "when" the boundary-posts of the new and better day for mankind will be raised. And if, in the course of this great battle for the emancipation of the human race, we should fall, those now in the rear will step forward; we shall fall with the consciousness of having done our duty as human beings, and with the conviction that the goal will be reached, however the powers hostile to humanity may struggle or strain in resistance.

OURS IS THE WORLD, DESPITE ALL; – THAT IS, FOR THEWORKER AND FOR WOMANFINISFOOTNOTES:As to her economic development, Germany has made rapid and long strides during the last twenty years; so rapid and so long that the progress has caused the Socialists of Germany, in more instances than one, to realize – and to say so – that, what with her own progress, and with outside circumstances, Germany was distancing England economically. This is true. But the same reason that argues, and correctly argues, the economic scepter off the hands of England places it, not in those of Germany, but in the hands of the United States.

As to her social development, Germany is almost half a revolutionary cycle behind. Her own bourgeois revolution was but half achieved. Without entering upon a long list of specifications, it is enough to indicate the fact that Germany is still quite extensively feudal in order to suggest to the mind robust feudal boulders, left untouched by the capitalist revolution, and strewing, aye, obstructing the path of the Socialist Movement in that country. The social phenomenon has been seen of an oppressed class skipping an intermediary stage of vassalage, and entering, at one bound, upon one higher up. It happened, for instance, with our negroes here in America. Without first stepping off at serfdom, they leaped from chattel slavery to wage slavery. What happened once may happen again. But in the instance cited and all the others that we can call to mind, it happened through outside intervention. Can Germany perform the same feat alone, unaided? Do events point in that direction? Or do they rather point in the direction that the work, now being realized there as demanding immediate attention, and alone possible and practicable, is the completion of the capitalist revolution, first of all?

But even discounting both these objections – granting that both in point of economic and of social development Germany were ripe for the Socialist Revolution – her geographic location prevents her leadership. No one single State of the forty-four of the Union, not even the Empire State of New York, however ripe herself, could lead in the overthrow of capitalist rule in America unless the bulk of her sister States were themselves up to a certain minimum of ripeness. Contrariwise, any attempt by even such a State would be promptly smothered. What is true of any single State of the Union is true of any one country of Europe. It is, therefore, true of Germany. Whatever doubt there be as to Germany's ripeness, there can be none as to the utter unripeness of all the other European countries with the single exceptions of France and Belgium, – and surely none as to Russia, that ominous cloud to the East, well styled the modern Macedon to the modern Greek States of the nations of Western Europe. Though there is no "District of Columbia" in Europe, the masses would be mobilized from the surrounding hives of the Cimmerian Darkness of feudo-capitalism, and they would be marched convergently with as much precision and despatch upon the venturesome leader. And what is true as to Germany on this head is true of any other European country. Facts and their relations to one another must be ever kept in sight. 'Tis the only way to escape illusions – and their train of troubles.

For the rest, not the sordid competitive spirit of the bourgeois world, but that noble and ennobling emulation, cited by the Author in a quotation from John Stuart Mill, animates the nations of the world that are now racing towards the overthrow of capitalist domination. Surely none will begrudge laurels due that one that shall be the first to scale the ramparts of the international burg of capitalism, strike the first blow, and give the signal for the final emancipation of the human race. – The Translator.]

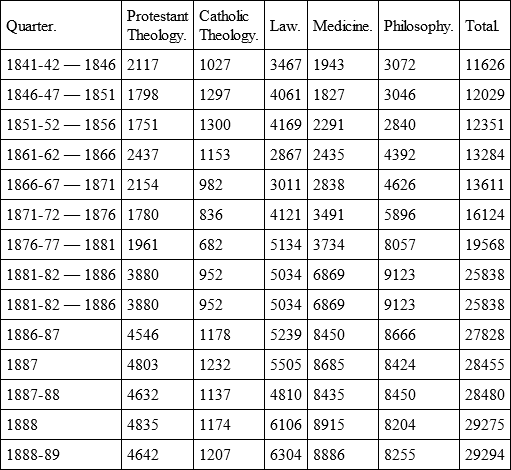

During the summer six months of 1893 – notably the weaker of the two seasons – the total number of students, exclusive of the University of Brunswick, of which we had no returns, had risen to 31,976. Unfortunately we had no like classification of the students, and are hence prevented from inserting it in the above table.

The table shows that from 1841-2 to 1871 the number of students increased little, and less than the population. From that date on the increase was by leaps and bounds, until 1886-7; from this date on the increase is again slow. From 1871 to 1888-9 the number of students increased more than 116 per cent. It is an interesting fact that the study of theology decreased steadily until 1881, but increased thereupon all the quicker until it reached high-water mark in 1888. The reason was that the excess of the supply for all the other posts increased in such measure that it was difficult to secure a place. People then turned to theology which had been neglected during the previous ten years.

1

Bachofen's book appeared in 1861 under the title, "Das Mutterrecht" (Mother-right) "Eine Untersuchung ueber die Gynaekokratie der Alten Welt nach ihrer religioesen und rechtlichen Natur," Stuttgart, Krais & Hoffmann. Morgan's fundamental work, "Ancient Society," appeared in a German translation in 1891, J. H. W. Dietz, Stuttgart. From the same publisher there appeared in German: "The Origin of the Family, of Private Property and the State, in support of Lewis H. Morgan's Investigations," by Frederick Engels. Fourth enlarged edition, 1892. Also "Die Verwandtschafts-Organisationen der Australneger. Ein Beitrag zur Entwickelungsgeschichte der Familie," by Heinrich Cunow, 1894.

[The perspective into which the Pleiades of distinguished names are thrown in the text just above is apt to convey an incorrect impression, and the impression is not materially corrected in the subsequent references to them. Neither Bachofen, nor yet Tylor, McLennan or Lubbock contributed to the principles that now are canons in ethnology. They were not even path-finders, valuable though their works are.

Bachofen collected, in his work entitled "Das Mutterrecht," the gleanings of vast and tireless researches among the writings of the ancients, with an eye to female authority. Subsequently, and helping themselves more particularly to the more recent contributions to archeology, that partly dealt with living aborigines, Tylor, McLennan and Lubbock produced respectively, "Early History of Mankind;" "Primitive Marriage;" and "Pre-Historic Times" and "Origin of Civilization." These works, though partly theoretic, yet are mainly descriptive. By an effort of genius – like the wood-pecker, whose instinct tells it the desired worm is beneath the bark and who pecks at and round about it – all these men, Bachofen foremost, scented sense in the seeming nonsense of ancient traditions, or surmised significance in the more recently ascertained customs of living aborigines. But again, like the wood-pecker, that has struck a bark too thick for its bill, these men could not solve the problem they were at. They lacked the information to pick, and they had not, nor were they so situated as to furnish themselves with, the key to open the lock. Morgan furnished the key.

Lewis Henry Morgan, born In Aurora, N. Y., November 21, 1818, and equipped with vast scholarship and archeological information, took up his residence among the Iroquois Indians, by whom, the Hawk gens of the Seneca tribe, he was eventually adopted. The fruit of his observations there and among other Indian tribes that he visited even west of the Mississippi, together with simultaneous information sent him by the American missionaries in the Sandwich Islands, was a series of epoch-making works, "The League of the Iroquois," "Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family," and "Ancient Society," which appeared in 1877. A last and not least valuable work was his "Houses and Houselife of the American Aborigines." A solid foundation was now laid for the science of ethnology and anthropology. The problem was substantially solved.

The robust scientific mind of Karl Marx promptly absorbed the revelations made by Morgan, and he recast his own views accordingly. A serious ethnological error had crept into his great work, "Capital," two editions of which had been previously published in German between 1863-1873. A footnote by Frederick Engels (p. 344, Swan, Sonnenschein & Co., English edition, 1886) testifies to the revolution Morgan's works had wrought on the ethnological conceptions of the founder of Socialist economics and sociology.

Subsequently, Frederick Engels, planted squarely on the principles established by Morgan, issued a series of brilliant monographs, in which, equipped with the key furnished by Morgan and which Engels' extensive economic and sociologic knowledge enabled him to wield with deftness, he explained interesting social phenomena among the ancients, and thereby greatly enriched the literature of social science.

Finally, Heinrich Cunow, though imagining to perceive some minor flaws in some secondary parts of Morgan's theory, placed himself in absolute accord with the body of Morgan's real work, as stated later in the text in a quotation from Cunow; and, following closely in Morgan's footsteps, made and published interesting independent researches on the system of consanguinity among the Austral-Negros. – The Translator.]

2

In his book against us, Ziegler ridicules the idea of attributing to myths any significance whatever in the history of civilization. In that notion stands betrayed the superficial nature of so-called scientists. They do not recognize what they do not see. A deep significance lies at the bottom of myths. They have grown out of the people's soul; out of olden morals and customs that have gradually disappeared, and now continue to live only in the myth. When we strike facts that explain a myth we are in possession of solid ground for its interpretation.

3

Bachofen: "Das Mutterrecht."

4

Totem-group means generation-group. Each grade or generation has its own totem-animal. For instance: Opossum, emu, wolf, bear, etc., after which the group is named. The totem-animal frequently enjoys great honor. It is held sacred with the respective group, and its members may neither kill the animal, nor eat its flesh. The totem-animal has a similar significance to the patron saint of the guild in the Middle Ages.

5

In the oldest ward of the city of Prague, there is a small synagogue that comes down from the sixth century of our reckoning, and is said to be the oldest synagogue in Germany. If the visitor steps down about seven steps into the half-dark space, he discovers in the opposite wall several target-like openings that lead into a completely dark room. To the question, where these openings lead to our leader answered: "To the woman's compartment, whence they witness the service." The modern synagogues are much more cheerfully arranged, but the separation of the women from the men is preserved.

6

Frederick Engels, "The Origin of the Family."

7

Frederick Engels, ubi supra.

8

Book of Judges, 20, 21 and sequel.

9

Bachofen: "Das Mutterrecht."

10

Of the theater, to which women had no access.

11

Johann Scherr, "Deutsche Kultur-und Sittengeschichte: " Leipsic, 1887. Otto Wigand. As is known, Suderman deals with the same subject in his play, "Die Ehre."

12

Plato, "The Republic," Book V.

13

Leon Bichter, "La Femme Libre."

14

Bachofen. "Das Mutterrecht."

15

K. Kautsky, "Die Entstehung der Ehe und der Familie," Kosmos, 1883.

16

Montegazza, "L'Amour dans l'Humanite."

17

Joh. David Michaelis, "Mosaisches Recht," Reutlingen, 1793.

18

Karl Heinzen, "Ueber die Rechte und Stellung der Frauen."

19

Born 106 before our reckoning.

20

He lived from 527 to 565 of our reckoning.

21

Augustus, the son of Caesar by adoption, was of the Julian gens, hence the title "Julian" law.

22

Tarnowsky. "Die krankhaften Erscheinungen des Geschlechtsinnes." Berlin, August Hirschwald.

23

Tacitus, "Histories," Book I.

24

Montegazza "L'Amour dans l'Humanite."

25

Matthew, ch. 19; 11 and 12.

26

I. Corinthians, ch. 7; 1 and 38.

27

Peter I., ch. 3; 1.

28

Paul: Ephesians, ch. 5; 23.

29

Paul: I. Corinthians, ch. 11; 7.

30

I. Timothy, ch. 2; 11 and 12.

31

I. Corinthians, ch. 14; 34 and 35.

32

This was a move that the parish priests of the diocese of Mainz, among others, complained against, expressing themselves this wise: "You Bishops and Abbots possess great wealth, a kingly table, and rich hunting equipages; we, poor, plain priests have for our comfort only a wife. Abstinence may be a handsome virtue, but, in point of fact, it is hard and difficult." – Yves-Guyot: "Les Theories Sociales du Christianisme."

33

Buckle, in his "History of Civilization in England," furnishes a large number of illustrations on this head.

34

Engels' "Der Ursprung der Familie."

35

The same thing happened under the rule of the muir in Russia. See Lavelaye: "Original Property."

36

"Eyn iglich gefurster man, der ein kindbette hat, ist sin kint eyn dochter, so mag eer eyn wagen vol bornholzes von urholz verkaufen of den samstag. Ist iz eyn sone, so mag he iz tun of den dinstag und of den samstag von ligenden holz oder von urholz und sal der frauwen davon kaufen, win und schon brod dyeweile sie kintes june lit," – G. L. v. Maurer; "Geschichte der Markenverfassung in Deutschland."

37

"Bettmund," "Jungfernzins," "Hemdschilling," "Schuerzenzins," "Bunzengroschen."

38

"Aber sprechend die Holflüt, weller hie zu der helgen see kumbt, der sol einen meyer (Gutsverwalter) laden und ouch sin frowen, da sol der meyer lien dem brütigan ein haffen, da er wol mag ein schaff in geseyden, ouch sol der meyer bringen ein fuder holtz an das hochtzit, ouch sol ein meyer und sin frow bringen ein viertenteyl eines schwynsbachen, und so die hochtzit vergat, so sol der brütigan den meyer by sim wib lassen ligen die ersten nacht, oder er sol sy lösen mit 5 schilling 4 pfenning." – I., p. 43.

39

"History of the Abolition of Serfdom in Europe to the Middle of the 19th Century." St. Petersburg, 1861.

40

Memminger, Staelin and others. "Beschreibung der Wuertembergischen Aemter." Hormayr. "Die Bayern im Morgenlande." Also Sugenheim.

41

"Ueber Stetigung und Abloesung der baeuerlichen Grundlasten mit besonderer Ruecksicht auf Bayern, Wuertemberg, Baden, Hessen, Preussen und Oesterreich." Landshut, 1848.

42

A poem of Albrecht von Johansdorf, in the collection of "Minnesang-Fruehling" (Collection of Lachman and Moritz Haupt; Leipsic, 1857; S. Hirtel), has this passage:

"waere ez niht unstaeteder Zwein wiben wolte sin fur eigen jehen,bei diu tougenliche? sprechet, herre, wurre ez iht?(man sol ez den man erlouben und den vrouwen nicht.)"The openness, with which two distinct rights, according to sex, are here considered a matter of course, corresponds with views that are found in force even to this day.

43

Dr. Karl Buecher, "Die Frauenfrage im Mittelalter," Tuebingen.

44

Dr. Karl Buecher.

45

Joh. Scherr, "Geschichte der Deutschen Frauenwelt," Leipsic, 1879.

46

Leon Richter reports in "La Femme Libre" the case of a servant girl in Paris who was convicted of infanticide by the father of the child himself, a respected and religious lawyer, who sat on the jury. Aye, worse: the lawyer in question was himself the murderer, and the mother was entirely guiltless, as, after her conviction, she herself declared in court.

47

Dr. Karl Hagen, "Deutschlands Literarische und Religioese Verhaeltnisse im Reformationszeitalter." Frankfurt-on-the-Main, 1868.

48

II., 146, Jena, 1522.

49

Dr. Karl Hagen.

50

Jacob Grimm informs us ("Deutsche Rechtsalterthuemer. Weisthum aus dem Amte Blankenburg"):

"Daer ein Man were, der sinen echten wive ver frowelik recht niet gedoin konde, der sall si sachtelik op sinen ruggen setten und draegen sie over negen erstnine und setten sie sachtelik neder sonder stoeten, slaen und werpen und sonder enig quaed woerd of oevel sehen, und roipen dae sine naebur aen, dat sie inne sines wives lives noet helpen weren, und of sine naebur dat niet doen wolden of kunden, so sall be si senden up die neiste kermisse daerbl gelegen und dat sie sik süverlik toe make und verzere und hangen ör einen buidel wail mit golde bestikt up die side, dat sie selft wat gewerven kunde: kumpt sie dannoch wider ungeholpen, so help ör dar der duifel."

As appears from Grimm, the German peasant of the Middle Ages looked in marriage, first of all, for heirs. If he was unable himself to beget these, he then, as a practical man, left the pleasure, without special scruples, to some one else. The main thing was to gain his object. We repeat it: Man does not rule property, property rules him.

51

Johann Janssen, "Geschichte des Deutschen Volkes," 1525-1555, Freiburg.

52

Which is perfectly correct, and also explainable, seeing that the Bible appeared at a time when polygamy extended far and wide among the peoples of the Orient and the Occident. In the sixteenth century, however, it was in strong contradiction with the standard of morality.

53

Johann Janssen.

54

Johann Janssen. Vol. III.

55

Dr. Karl Buecher, "Die Frauenfrage im Mittelalter."

56

Johann Scherr: "Geschichte der Deutschen Frauenwelt."

57

Karl Kautsky, "Ueber den Einfluss der Volksvermehrung auf den Fortschritt der Gesellschaft." Vienna, 1880.

58

Mainlaender, "Philosophie der Erlösung," Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1886, E. Koenitzer.

59

D. A. Debay, "Hygiene et Physiologue du Marriage," Paris, 1884. Quoted in "Im Freien Reich" by Ioma v. Troll-Borostyani, Zurich, 1884.

60

"Das Geschlechtsleben des Weibes, in physiologischer, pathologischer und therapeutischer Hinsicht dargestellt."

61

"Die Prostitution vor dem Gesetz," by Veritas. Leipsic, 1893.

62

V. Oettingen, "Moralstatistik." Erlangen, 1882.

63

"Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie," Vol. I, Stuttgart, 1883.

64

Vol. II. Leipsic, 1887.

65

"The moods and feelings in and which husband and wife approach each other, exercise, without a doubt, a definite influence upon the result of the sexual act, and transmit certain characteristics to the fruit." Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, "The Moral Education of the Young In Relation to Sex." See also Goethe's "Elective Affinities," where he sketches clearly the influence exerted by the feelings of two beings who approach each other for intimate intercourse.

66

"Denkwuerdigkeiten," Vol. I, p. 239, Leipsic, F. A. Brockhaus.

67

"Mr. E., a manufacturer … informed me that he employed females exclusively, at his power-looms … gives a decided preference to married females, especially those who have families at home dependent on them for support; they are attentive, docile, more so than unmarried females, and are compelled to use their utmost exertions to procure the necessities of life. Thus are the virtues, the peculiar virtues of the female character to be perverted to her injury – thus all that is most dutiful and tender in her nature is made a means of her bondage and suffering." Speech of Lord Ashley, March 15, 1884, on the Ten Hour Factory Bill. Marx's "Capital."

68

"Die Frau auf dem Gebiete der Nationaloekonomie."

69

See "Fuerst Bismarck und seine Leute," Von Busch.

70

Sections 180 and 181.

71

"The Physiology of Love."

72

Alexander Dumas says rightly, In "Monsieur Alfonse: " "Man has built two sorts of morals; one for himself, one for his wife; one that permits him love with all women, and one that, as indemnity for the liberty she has forfeited forever, permits her love with one man only."

73

L. Bridel, "La Puissance Maritale," Lausanne. 1879.

74

v. Oettingen, "Moralstatistik," Erlangen, 1882.

75

v. Oettingen, "Moralstatistik."

76

[According to the census of 1900, there were in the United States 198,914 divorced persons: males 84,237, females 114,677. The percentage of divorced to married persons was 0.7. The census warns, however, that "divorced persons are apt to be reported as single, and so the census returns in this respect should not be accepted as a correct measure of the prevalence of divorce throughout the country." – The Translator.]

77

v. Oettingen, "Moralstatistik."

78

In his work frequently cited by us, "Die Frauenfrage im Mittelalter," Buecher laments the decay of marriage and of family life; he condemns the increasing female labor in industry, and demands a "return" to the "real domain of woman," where she alone produces "values" in the house and the family. The endeavors of the modern friends of woman appear to him as "dilettanteism" and he hopes finally "that the movement may be switched on the right track," but he is obviously unable to point to a successful road. Neither is that possible from the bourgeois standpoint. The marriage conditions, like the condition of woman in general, have not been brought about arbitrarily. They are the natural product of our social development. But the social development of peoples does not cut capers, nor does it perpetrate any such false reasonings in a circle; it takes its course obedient to imminent laws. It is the mission of the student of civilization to discover these laws, and, planted upon them, to show the way for the removal of existing evils.