полная версия

полная версияWoman under socialism

With the view of avoiding these evils of trade, evils that, as ever and everywhere, are hardest on the masses, "Consumers' Associations" have been set up. In Germany, the "Consumers' Association" plan, especially among the military and civil service employees, reaches such a point that numerous business houses have been ruined, and many are not far from the same fate. These Associations demonstrate the superfluousness of trade in a differently organized society.171 In that consists their principal merit. The material advantages are not great for the members; neither are the facilities that they offer enough to enable the members to discover any material improvement in their condition. Not infrequently is their administration poor, and the members must pay for it. In the hands of capitalists, these Associations even become an additional means to chain the workingman to the factory, and they are used as weapons to depress wages. The founding of these "Consumers' Associations" is, however, a symptom that the evils of trade and at least the superfluousness of the middlemen have been realized in wide circles. Society will reach that point of organization at which trade becomes wholly superfluous; the product will reach the consumer without the intervention of any middlemen other than those who attend to its transportation from place to place, and who are in the service of society. A natural demand, that flows from the collective procurement of food, is its collective preparation for the table upon a large scale, whereby a further and enormous saving would be made of energy, space, material and all manner of expenditures.

* * * * *The economic revolution in industry and transportation has spread to agriculture also, and in no slight degree. Commercial and industrial crises are felt in the country as well. Many relatives of families located in the country are partially or even wholly engaged in industrial establishments in cities, and this sort of occupation is becoming more and more common because the large farmers find it convenient to convert on their own farms a considerable portion of their produce. They thereby save the high cost of transporting the raw product – potatoes that are used for spirits, beets for sugar, grain for flour or brandy or beer. Furthermore, they have on their own farms cheaper and more willing labor than can be got in the city, or in industrial districts. Factories and rent are considerably cheaper, taxes and licenses lower, seeing that, to a certain extent, the landed proprietors are themselves lawgivers and law officers: from their midst numerous representatives are sent to the Reichstag: not infrequently they also control the local administration and the police department. These are ample reasons for the phenomenon of increasing numbers of funnel-pipes in the country. Agriculture and industry step into ever closer interrelation with each other – an advantage that accrues mainly to the large landed estates.

The point of capitalist development reached in Germany also by agriculture has partially called forth conditions similar to those found in England and the United States. As with the small and middle class industries, so likewise with the small and middle class farms, they are swallowed up by the large. A number of circumstances render the life of the small and middle class farmer ever harder, and ripen him for absorption by the large fellow.

No longer do the one-time conditions, as they were still known a few decades ago, prevail in the country. Modern culture now pervades the country in the remotest corners. Contrary to its own purpose, militarism exercises a certain revolutionary influence. The enormous increase of the standing army weighs, in so far as the blood-tax is concerned, heaviest of all upon the country districts. The degeneration of industrial and city life compels the drawing of by far the larger portion of soldiers from the rural population. When the farmer's son, the day laborer, or the servant returns after two or three years from the atmosphere of the city and the barracks, an atmosphere not exactly impregnated with high moral principles; – when he returns as the carrier and spreader of venereal diseases, he has also become acquainted with a mass of new views and wants whose gratification he is not inclined to discontinue. Accordingly, he makes larger demands upon life, and wants higher wages; his frugality of old went to pieces in the city. Transportation, ever more extended and improved, also contributes toward the increase of wants in the country. Through intercourse with the city, the rustic becomes acquainted with the world from an entirely new and more seductive side: he is seized with new ideas: he learns of the wants of civilization, thitherto unknown to him. All that renders him discontented with his lot. On top of that, the increasing demands of the State, the province, the municipality hit both farmer and farmhand, and make them still more rebellious.

True enough, many farm products have greatly risen in value during this period, but not in even measure with the taxes and the cost of living. On the other hand, transmarine competition in food materially contributes toward reducing prices: this reduces incomes: the same can be counterbalanced only by improved management: and nine-tenths of the farmers lack the means thereto. Moreover, the farmer does not get for his product the price paid by the city: he has to deal with the middlemen: and these hold him in their clutches. The broker or dealer, who at given seasons traverses the country and, as a rule, himself sells to other middlemen, wants to make his profits: the gathering of many small quantities gives him much more trouble than a large invoice from a single large holder: the small farmer receives, as a consequence, less for his goods than the large farmer. Moreover, the quality of the products from the small farmer is inferior: the primitive methods that are there generally pursued have that effect: and that again compels the small farmer to submit to lower prices. Again, the farm owner or tenant can often not afford to wait until the price of his goods rises. He has payments to meet – rent, interest, taxes; he has loans to cancel and debts to settle with the broker and his hands. These liabilities are due on fixed dates: he must sell however unfavorable the moment. In order to improve his land, to provide for co-heirs, children, etc., the farmer has contracted a mortgage: he has no choice of creditor: thus his plight is rendered all the worse. High interest and stated payments of arrears give him hard blows. An unfavorable crop, or a false calculation on the proper crop, for which he expected a high price, carry him to the very brink of ruin. Often the purchaser of the crop and the mortgagee are one and the same person. The farmers of whole villages and districts thus find themselves at the mercy of a few creditors. The farmers of hops, wine and tobacco in Southern Germany; the truck farmers on the Rhine; the small farmers in Central Germany – all are in that plight. The mortgagee sucks them dry; he leaves them, apparent owners of a field, that, in point of fact, is theirs no longer. The capitalist vampire often finds it more profitable to farm in this way than, by seizing the land itself and selling it, or himself doing the farming. Thus many thousand farmers are carried on the registers as proprietors, who, in fact, are no longer such. Thus, again, many a large farmer – unskilled in his trade, or visited by misfortune, or who came into possession under unfavorable circumstances – also falls a prey to the executioner's axe of the capitalist. The capitalist becomes lord of the land; with the view of making double gains he goes into the business of "butchering estates: " he parcels out the domain because he can thereby get a larger price than if he sold it in lump: then also he has better prospects of plying his usurious trade if the proprietors are many and small holders. It is well known that city houses with many small apartments yield the largest rent. A number of small holders join and buy a portion of the parcelled-out estate: the capitalist benefactor is ready at hand to pass larger tracts over to them on a small cash payment, securing the rest by mortgage bearing good interest. This is the milk in the cocoanut. If the small holder has luck and he succeeds, by utmost exertion, to extract a tolerable sum from the land, or to obtain an exceptionally cheap loan, then he can save himself; otherwise he fares as shown above.

If a few heads of cattle die on the hands of the farm-owner or tenant, a serious misfortune has befallen him; if he has a daughter who marries, her outfit augments his debts, besides his losing a cheap labor-power; if a son marries, the youngster wants a piece of land or its equivalent in money. Often this farmer must neglect necessary improvements: if his cattle and household do not furnish him with sufficient manure – a not unusual circumstance – then the yield of the farm declines, because its owner cannot buy fertilizers: often he lacks the means to obtain better seed. The profitable application of machinery is denied him: a rotation of crops, in keeping with the chemical composition of his farm, is often not to be thought of. As little can he turn to profit the advantages that science and experience offer him in the conduct of his domestic animals: the want of proper food, the want of proper stabling and attention, the want of all other means and appliances prevent him. Innumerable, accordingly, are the causes that bear down upon the small and middle class farmer, drive him into debt, and his head into the noose of the capitalist or the large holder.

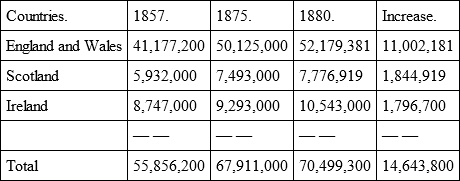

The large landholders are generally intent upon buying up the small holdings, and thereby "rounding up" their estates. The large capitalist magnates have a predilection for investments in land, this being the safest form of property, one, moreover, that, with an increasing population, rises in value without effort on the part of the owners. England furnishes the most striking instance of this particular increase of value. Although due to international competition in agricultural products and cattle-raising, the yield of the land decreased during the last decades, nevertheless, seeing that in Scotland two million acres were converted into hunting grounds, that in Ireland four million acres lie almost waste, that in England the area of agriculture declined from 19,153,900 acres in 1831, to 15,651,605 in 1880, a loss of 3,484,385 acres, which have been converted into meadow lands, rent increased considerably. The aggregate rent from country estates amounted, in pounds sterling, to: —

Accordingly, an increase of 26.2 per cent. within 23 years, and that without any effort on the part of the owners. Although, since 1880, due to the ever sharper international competition in food, the agricultural conditions of England and Ireland have hardly improved, the large English landlords have not yet ventured upon such large demands upon the population as have the continental, the German large landlords in particular. England knows no agricultural tariffs; and the demand for a minimum price, fixed by government, of such nature that they have been styled "price raisers" and as the large landlords of the East Elbe region together with their train-bands in the German Reichstag are insisting on at the cost of the propertyless classes, would raise in England a storm of indignation.

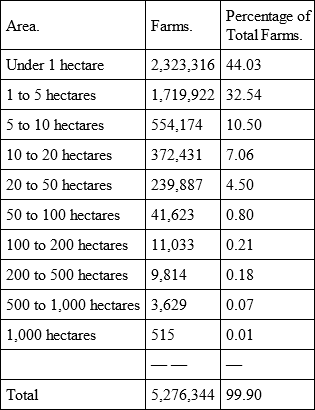

According to the agricultural statistics gathered in Germany on June 2, 1882, the farms fell into the following categories according to size: —

According to Koppe, a minimum of 6 hectares are requisite in Northern Germany for a farmer's family to barely beat itself through; in order to live in tolerable circumstances, 15 to 20 hectares are requisite. In the fertile districts of Southern Germany, 3 to 4 hectares are considered good ground to support a peasant family on. This minimum is reached in Germany by not four million farms, and only about 6 per cent. of the farmers have holdings large enough to enable them to get along in comfort. Not less than 3,222,270 farmers conduct industrial or commercial pursuits besides agriculture. It is a characteristic feature of the lands under cultivation that the farms of less than 50 hectares – 5,200,000 in all – contained only 3,747,677 hectares of grain lands, whereas the farms of more than 50 hectares – 66,000 in round figures – contained 9,636,246 hectares. One and a quarter per cent. of the farms contained 2½ times more grain land than the other 98¾ per cent. put together.

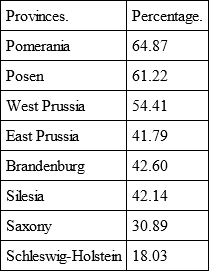

And yet the picture presented by these statistics falls by far short of the reality. It has not been ascertained among how many owners these 5,276,344 farms are divided. The number of owners is far smaller than that of the farms themselves: many are the owners of dozens of farms: it is in the instance of large farms, in particular, that many are held by one proprietor. A knowledge of the concentration of land is of the highest socio-political importance, yet on this point the agricultural statistics of 1882 leave us greatly in the lurch. A few facts are, nevertheless, ascertained from other sources, and they give an approximate picture of the reality. The percentages of large landed property – over 100 hectares – to the aggregate agricultural property was as follows: —

According to the memorial of the Prussian Minister of Agriculture, published in the bulletin of the Prussian Bureau of Statistics, the number of middle class farms sank, from 354,610 with 35,260,084 acres, in 1816, to 344,737 with 33,498,433 acres, in 1859. The number of these farms had, accordingly, decreased within that period by 9,873, and peasant property had been wiped out to the volume of 1,711,641 acres. The inquiry extended only to the provinces of Prussia, Posen (from 1823 on), Pomerania, exclusive of Stralsund; Brandenburg, Saxony, Silesia, and Westphalia.

What disappears as peasant property usually goes into large estates. In 1885, in the province of Pomerania, 62 proprietors held 118 estates; in 1891, however, the same number of proprietors held 203 estates with an area of 147,139 hectares. Altogether, there were in the province of Pomerania, in 1891, 1,353 noble and bourgeois landlords, owning 2,258 estates with 1,247,201 hectares.172 The estates averaged 551 hectares in size.

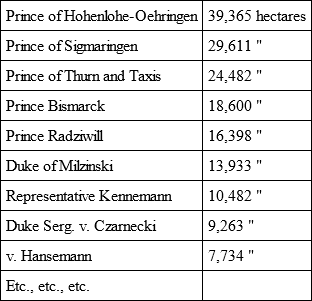

Our eastern provinces give this table of landlords for the year 1888: —

We see that we here have to do with owners of latifundia of first rank; and a portion of these gentlemen own also large estates in Southern Germany and Austria.

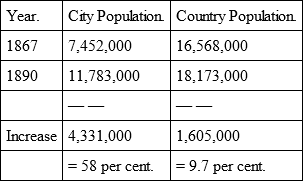

According to Conrad,173 there were in the year 1888, in East Prussia, 547 entails, of which 153 were instituted before the beginning of the nineteenth century. Entailed land is property that an heir can neither mortgage, divide nor alienate. The owner may go into bankruptcy through a dissolute life, but the entail and the income that flows therefrom remain unseizable. These entails, which only the very rich can institute, are steadily increasing in number since the last decades. The 547 entails in existence in the eastern provinces of Prussia in 1888, held by 529 persons, 20 of whom were bourgeois, embraced 1,408,860 hectares, or 2,454 hectares on an average. According to the statistical figures, submitted in the spring of 1894 by the Prussian Minister of Agriculture to the Agrarian Commission, the entails of Prussia embraced at that time 1,833,754 hectares with a net income of 22,992,000 marks. Estimating the holders of entails at 550, each has an unseizable income of 41,800 marks. Assuming, however, that these entails are concentrated in one province, it would mean that the whole province of Schleswig-Holstein, with an area of 1,890,000 hectares, belonged to 550 owners. In 1888 there were in the eastern provinces of Prussia 154 persons – among them 15 ruling Princes (the Kings of Prussia, Saxony, etc.); 89 Dukes, other Princes and Counts; 40 noblemen and 10 bourgeois – who alone owned 1,830 estates aggregating 1,768,648 hectares of land. Probably, the property of these persons has in the meantime increased considerably, seeing that a good portion of the net incomes from these estates is expended in acquiring new ones. The nobility of the first and second rank are the principal elements engaged in this gigantic concentration of landed property; but they are closely followed by the aristocracy of finance, who, with increasing predilection, invest their wealth in land, consisting mainly in magnificent woods, stocked with roe, deer and wild boar, that the owners may gratify their passion for the hunt. A large number of the baronial manors consist of the estates of dispossessed peasants, who were driven from their homes and reduced to day laborers. According to Neumann, in the provinces of East and West Prussia alone, there were from twelve to thirteen thousand small holdings appropriated in that way between 1825 to 1859. This process of dispossessing, proletarianizing the country population by the capitalist landlords, has the laying waste of the land as a natural consequence. The population emigrates, or moves to the cities and industrial centers. Woods and meadows gain upon cultivated lands, the remaining territories are operated with machinery, that render human labor superfluous, or that need such only for short periods during the plowing and sowing seasons, or when the crops are gathered. The rapidly increasing number of movable steam engines, already mentioned, consists mainly of engines employed in the cultivation of the land. The decrease of the rural population, resulting upon these and other causes of secondary nature, is sharply expressed in the statistics on population. Within the eight old provinces of Prussia, the proportion between the rural and the city population revealed, between 1867 and 1890, the following progression: —

The rapidity is obvious with which the city is surpassing the country population. But the situation is still more unfavorable to the country if the fact is considered that 148 communities, with from 5,000 to 40,000 inhabitants, and aggregating a population of 1,281,000 strong, are included in the rural but really belong to the industrial districts. They are essentially proletarian villages, located near large cities. Furthermore, 647 communities, with from 2,000 to 5,000 inhabitants, and aggregating a population of 1,884,000, are likewise included in the rural, while, to a perceptible degree, they belong to the industrial districts.

Similar conditions exist in Saxony and Southern Germany. In Baden and Wurtemberg also the population of many districts is on the decline. The small farmer can no longer hold his head above water; to thousands upon thousands of them the fate of a factory hand is inevitable; they enter the field of industry; and, with the help of their families, they cultivate during leisure hours the plot of land that may still be theirs. At the same time the large landlord's hunger for land knows no bounds; his appetite increases the more peasant lands he devours.

As in Germany so are things developing in neighboring Austria, where large landed property has long ruled almost unchecked. The difference there is that the Catholic Church shares the land with the nobility and the bourgeoisie. The process of smoking-out the farmer is in full swing in Austria. All manner of efforts are put forth in order to push the peasants and mountaineers of Tyrol, Salzburg, Steiermark, Upper and Lower Austria, etc., off their inherited patrimony and to drive them to relinquish their property. The spectacle, once presented to the world by England and Scotland, is now on the boards of the most beautiful and charming regions of Austria. Enormous tracts of land are bought in lump by rich men, and what cannot be bought outright is leased. Access to the valleys, manors, hamlets and even houses is thus barred by these new masters, and stubborn owners of separate small holdings are driven by all manner of chicaneries to dispose of their property at any price to these wealthy owners of the woodlands. Old farmlands, on which numerous generations have been supported for thousands of years, are being transformed into wilderness, in which the roe and the deer house, while the mountains, that the noble or bourgeois capitalist calls his own, become the abode of large herds of chamois. Whole communities are pauperized, the turning of their cattle upon the Alpine pastures being made impossible to them, or their right to do so being even disputed. And who is it that thus raises his hand against the peasant's property and independence? Princes, noblemen and rich bourgeois. Side by side with Rothschild and Baron Mayer-Melnhof are found the Dukes of Koburg and Meiningen, the Princes of Hohenlohe, the Prince of Lichtenstein, the Duke of Braganza, Prince Rosenberg, Prince Pless, the Counts of Schoenfeld, Festetics, Schafgotsca, Trautmannsdorff, the hunting association of the Count of Karolysche, the hunting association of Baron Gustaedtsche, the noble hunting association of Bluehnbacher, etc.

Large landed property is everywhere on the increase in Austria. The number of large landlords rose 9.5 per cent. from 1873 to 1891, and that means a considerable decrease of small holders: land cannot be increased.

In Lower Austria, of a total area embracing 3,544,596 yokes, 521,603 were taken up by large estates (247 owners), and 94,882 yokes by the Church. Nine families alone owned, in the middle of the eighties, 157,000 yokes, among these owners was the Count of Hoyos, with 54,000 yokes. The area of Moravia is 2,222,190 hectares. Of these, the Church held 78,496, 3.53 per cent.; 145 private persons held 525,632, and one of these alone held 107,247 hectares. Of Austrian Silesia's area of 514,085 hectares, the Church owned 50,845, or 9.87 per cent.; 36 landlords owned 134,226, or 26.07 per cent. The area of Bohemia is 5,196,700 hectares: of these the clergy owned 103,459 hectares; 362 private persons owned 1,448,638. This number is distributed among Prince Colloredo-Mansfeld with 58,239 hectares; Prince Fuerstenberg with 39,814; Imperial Duke Waldstein with 37,989; Prince Lichtenstein with 37,937; the Count of Czerin with 32,277; the Count of Clam-Gallas with 31,691; Emperor Franz Joseph with 28,800; the Count von Harrach with 28,047; Prince von Lobkowitz with 27,684; Imperial Count Kinsky with 26,265; the Count of Buquoy with 25,645; the Prince of Thurn and Taxis with 24,777; Prince Schwarzenberg with 24,037; Prince Metternich-Winneburg with 20,002; Prince Auersperg with 19,960; Prince Windischgraetz with 19,920 hectares, etc.174

The absorption by the large landlords of the small holdings in land frequently proceeds in "alarming manner." For instance, in the judicial district of Aflenz, community of St. Ilgen, an Alpine hill of over 5,000 yokes, with pasture ground for 300 head of cattle, and a contiguous peasant estate of 700 yokes, was all converted into a hunting ground. The same thing happened with Hoellaep, located in the community of Seewiesen, which had pasture land for 200 head of cattle. In the same judicial district of Aflenz, 47 other pieces of land, holding 840 head of cattle, were gradually absorbed and turned into hunting grounds. Similar doings are reported from all parts of the Alps. In Steiermark, a number of peasants find it more profitable to sell the hay to the lordly hunters as feed for the game in winter, than give it to their own cattle. In the neighborhood of Muerzzuschlag, some peasants no longer keep cattle, but sell all the feed for the support of the game.

In the judicial district of Schwarz, 7, and in the judicial district of Zell, 16 Alpine hills, formerly used for pasture, were "cashiered" by the new landlords and converted into hunting grounds. The whole region of the Karwendel mountain has been closed to cattle. It is generally the high nobility of Austria and Germany, together with rich bourgeois upstarts, who bought up Alpine stretches of land of 70,000 yokes and more at a clip and had them arranged for hunting parks. Whole villages, hundreds upon hundreds of holdings are thus wiped out of existence; the inhabitants are crowded off; and in the place of human beings, together with cattle meet for their sustenance, roes, deer and chamois put in their appearance. Oddest of all, more than one of the men, who thus lay whole provinces waste, is seen rising in the parliaments and declaiming on the "distress of landed property," and abuses his power to secure the protection of Government in the shape of duties on corn, wood and meat, and premiums on brandy and sugar, – all at the expense of the propertyless masses.