полная версия

полная версияWoman under socialism

In general, public opinion is agreed that marriage is not advisable for men under twenty-four or twenty-five years of age. Twenty-five is the marriageable age for men fixed by the civil code, with an eye to the civic independence that, as a rule, is not gained before that age. Only with persons who are in the agreeable position of not having to first conquer independence – with people of princely rank – does public opinion consider it proper when occasionally the men marry at the age of eighteen or nineteen, the girls at that of fifteen or sixteen. The Prince is declared of age with his eighteenth year, and considered capable to govern a vast empire and numerous people. Common mortals acquire the right to govern their possible property only at the age of twenty-one.

The difference of opinion as to the age when marriage is desirable shows that public opinion judges by the social standing of the bride and bridegroom. Its reasons have nothing to do with the human being as a natural entity, or with its natural instincts. It happens, however, that Nature's impulses do not yoke themselves to social conditions, nor to the views and prejudices that spring from them. So soon as man has reached maturity, the sexual instincts assert themselves with force; indeed, they are the incarnation of the human being, and they demand satisfaction from the mature being, at the peril of severe physical and mental suffering.

The age of sexual ripeness differs according to individuals, climate and habits of life. In the warm zone it sets in with the female sex, as a rule, at the age of eleven to twelve years, and not infrequently are women met with there, who, already at that age, carry offspring on their arms; but at their twenty-fifth or thirtieth year, these have lost their bloom. In the temperate zone, the rule with the female sex is from the fourteenth to the sixteenth year, in some cases later. Likewise is the age of puberty different between country and city women. With healthy, robust country girls, who move much in the open air and work vigorously, menstruation sets in later, on the average, than with our badly nourished, weak, hypernervous, ethereal city young ladies. Yonder, sexual maturity develops normally, with rare disturbances; here a normal development is the exception: all manner of illnesses set in, often driving the physician to desperation. How often are not physicians compelled to declare that, along with a change of life, the most radical cure is marriage. But how apply such a cure? Insuperable obstacles rise against the proposition.

All this goes to show where the change must be looked for. In the first place, the point is to make possible a totally different education, one that takes into consideration the physical as well as the mental being; in the second place, to establish a wholly different system of life and of work. But both of these are, without exception, possible for all only under wholly different social conditions.

Our social conditions have raised a violent contradiction between man, as a natural and sexual being, on the one hand, and man as a social being on the other. The contradiction has made itself felt at no period as strongly as at this; and it produces a number of diseases into whose nature we will go no further, but that affect mainly the female sex: in the first place, her organism depends, in much higher degree than that of man, upon her sexual mission, and is influenced thereby, as shown by the regular recurrence of her periods; in the second place, most of the obstacles to marriage lie in the way of women, preventing her from satisfying her strongest natural impulse in a natural manner. The contradiction between natural want and social compulsion goes against the grain of Nature; it leads to secret vices and excesses that undermine every organism but the strongest.

Unnatural gratification, especially with the female sex, is often most shamelessly promoted. More or less underhandedly, certain preparations are praised, and they are recommended especially in the advertisements of most of the papers that penetrate into the family circle as especially devoted to its entertainment. These puffs are addressed mainly to the better situated portion of society, seeing the prices of the preparations are so high that a family of small means can hardly come by them. Side by side with these shameless advertisements are found the puffs – meant for the eyes of both sexes – of obscene pictures, especially of whole series of photographs, of poems and prose works of similar stripe, aimed at sexual incitation, and that call for the action of police and District Attorneys. But these gentlemen are too busy with the "civilization, marriage and family-destroying" Socialist movement to be able to devote full attention to such machinations. A part of our works of fiction labors in the same direction. The wonder would be if sexual excesses, artificially incited, besides, failed to manifest themselves in unhealthy and harmful ways, and to assume the proportions of a social disease.

The idle, voluptuous life of many women in the property classes; their refined measures of nervous stimulants; their overfeeding with a certain kind of artificial sensation, cultivated in certain lines on the hothouse plan, and often considered the principal topic of conversation and sign of culture by that portion of the female sex that suffers of hypersensitiveness and nervous excitement; – all this incites still more the sexual senses, and naturally leads to excesses.

Among the poor, it is certain exhausting occupations, especially of a sedentary nature, that promotes congestion of blood in the abdominal organs, and promotes sexual excitation. One of the most dangerous occupations in this direction is connected with the, at present, widely spread sewing machine. This occupation works such havoc that, with ten or twelve hours' daily work, the strongest organism is ruined within a few years. Excessive sexual excitement is also promoted by long hours of work in a steady high temperature, for instance, sugar refineries, bleacheries, cloth-pressing establishments, night work by gaslight in overcrowded rooms, especially when both sexes work together.

A succession of further phenomena has been here unfolded, sharply illustrative of the irrationableness and unhealthiness of modern conditions. These are evils deeply rooted in our social state of things, and removable neither by the moral sermonizings nor the palliatives that religious quacks of the male and female sexes have so readily at hand. The axe must be laid to the root of the evil. The question is to bring about a natural system of education, together with healthy conditions of life and work, and to do this in amplest manner, to the end that the normal gratification of natural and healthy instincts be made possible for all.

As to the male sex, a number of considerations are absent that are present with the female sex. Due to his position as master, and in so far as social barriers do not hinder him, there is on the side of man the free choice of love. On the other hand, the character of marriage as an institution for support, the excess of women, custom; – all these circumstances conspire to prevent woman from manifesting her will; they force her to wait till she is wanted. As a rule, she seizes gladly the opportunity, soon as offered, to reach the hand to the man who redeems her from the social ostracism and neglect, that is the lot of that poor waif, the "old maid." Often she looks down with contempt upon those of her sisters who have yet preserved their self-respect, and have not sold themselves into mental prostitution to the first comer, preferring to tread single the thorny path of life.

On the other hand, social considerations tie down the man, who desires to reach by marriage the gratification of his life's requirements. He must put himself the question: Can you support a wife, and the children that may come, so that pressing cares, the destroyers of your happiness, may be kept away? The better his marital intentions are, the more ideally he conceives them, the more he is resolved to wed only out of love, all the more earnestly must he put the question to himself. To many, the affirmative answer is, under the present economic conditions, a matter of impossibility: they prefer to remain single. With other and less conscientious men, another set of considerations crowd upon the mind. Thousands of men reach an independent position, one in accord with their wants, only comparatively late. But they can keep a wife in a style suitable to their station only if she has large wealth. True enough, many young men have exaggerated notions on the requirements of a so-called life "suitable to one's station." Nevertheless, they can not be blamed – as a result of the false education above described, and of the social habits of a large number of women, – for not guarding against demands from that quarter that are far beyond their powers. Good women, modest in their demands, these men often never come to know. These women are retiring; they are not to be found there where such men have acquired the habit of looking for a wife; while those whom they meet are not infrequently such as seek to win a husband by means of their looks, and are intent, by external means, by show, to deceive him regarding their personal qualities and material conditions. The means of seduction of all sorts are plied all the more diligently in the measure that these ladies come on in years, when marriage becomes a matter of hot haste. Does any of these succeed in conquering a husband, she has become so habituated to show, jewelry, finery and expensive pleasures, that she is not inclined to forego them in marriage. The superficial nature of her being crops up in all directions, and therein an abyss is opened for the husband. Hence many prefer to leave alone the flower that blooms on the edge of the precipice, and that can be plucked only at the risk of breaking their necks. They go their ways alone, and seek company and pleasure under the protection of their freedom. Deception and swindle are practices everywhere in full swing in the business life of capitalist society: no wonder they are applied also in contracting marriage, and that, when they succeed, both parties are drawn into common sorrows.

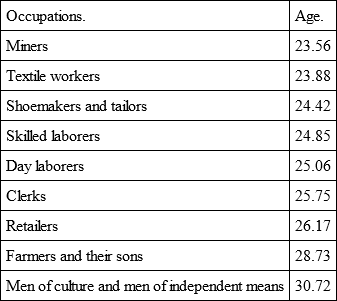

According to E. Ansell, the age of marriage among the cultured and independent males of England was, between 1840-1871, on an average 29.25 years. Since then the average has risen for many classes, by at least one year. For the different occupations, the average age of marriage, between 1880-1885, was as follows: —

These figures give striking proof of how social conditions and standing affect marriage.

The number of men who, for several reasons, are kept from marrying is ever on the increase. It is especially in the so-called upper ranks and occupations that the men often do not marry, partly because the demands upon them are too great, partly because it is just the men of these social strata who seek and find pleasure and company elsewhere. On the other hand, conditions are particularly unfavorable to women in places where many pensionaries and their families, but few young men, have their homes. In such places, the number of women who cannot marry rises to 20 or 30 out of every 100. The deficit of candidates for marriage affects strongest those female strata that, through education and social position, make greater pretensions, and yet, outside of their persons, have nothing to offer the man who is looking for wealth. This concerns especially the female members of those numerous families that live upon fixed salaries, are considered socially "respectable," but are without means. The life of the female being in this stratum of society is, comparatively speaking, the saddest of all those of her fellow-sufferers. It is out of these strata that is mainly recruited the most dangerous competition for the working-women in the embroidering, seamstress, flower-making, millinery, glove and straw hat sewing; in short, all the branches of industry that the employer prefers to have carried on at the homes of the working-women. These ladies work for the lowest wages, seeing that, in many cases, the question with them is not to earn a full livelihood, but only something over and above that, or to earn the outlay for a better wardrobe and for luxury. Employers have a predilection for the competition of these ladies, so as to lower the earnings of the poor working-woman and squeeze the last drop of blood from her veins: it drives her to exert herself to the point of exhaustion. Also not a few wives of government employes, whose husbands are badly paid, and can not afford them a "life suitable to their rank," utilize their leisure moments in this vile competition that presses so heavily upon wide strata of the female working class.

The activity on the part of the bourgeois associations of women for the abolition of female labor and for the admission of women to the higher professions, at present mainly, if not exclusively, appropriated by men, aims principally at procuring a position in life for women from the social circles just sketched. In order to secure for their efforts greater prospects of success, these associations have loved to place themselves under the protectorate of higher and leading ladies. The bourgeois females imitate herein the example of the bourgeois males, who likewise love such protectorates, and exert themselves in directions that can bring only small, never large results. A Sisyphus work is thus done with as much noise as possible, to the end of deceiving oneself and others on the score of the necessity for a radical change. The necessity is also felt to do all that is possible in order to suppress all doubts regarding the wisdom of the foundations of our social and political organization, and to prescribe them as treasonable. The conservative nature of these endeavors prevents bourgeois associations of women from being seized with so-called destructive tendencies. When, accordingly, at the Women's Convention of Berlin, in 1894, the opinion was expressed by a minority that the bourgeois women should go hand and hand with the working-women, i. e., with their Socialist citizens, a storm of indignation went up from the majority. But the bourgeois women will not succeed in pulling themselves out of the quagmire by their own topknots.

How large the number is of women who, by reason of the causes herein cited, must renounce married life, is not accurately ascertainable. In Scotland, the number of unmarried women of the age of twenty years and over was, towards the close of the sixties, 43 per cent. of the female population, and there were 110 women to every 100 men. In England, outside of Wales, there lived at that time 1,407,228 more women than men of the age of 20 to 40, and 359,966 single women of over forty years of age. Of each 100 women 42 were unmarried.

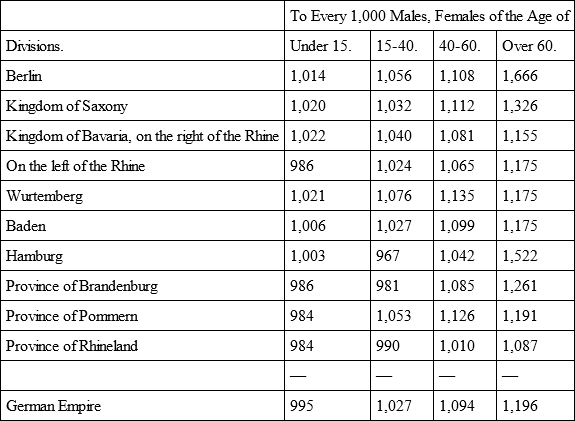

The surplus of women that Germany owns is very unevenly distributed in point of territories and age. According to the census of 1890, it stood: —98

Accordingly, of marriageable age proper, 15-40, the surplus of women in the German Empire amounts to 27 women to every 1,000 men. Seeing that, within these age periods, there are 9,429,720 male to 9,682,454 female inhabitants, there is a total female surplus of 252,734. In the same four age periods, the proportion of the sexes in other countries of Europe and outside of Europe stood as follows: —99

It is seen that all countries of the same or similar economic structure reveal the identical conditions with regard to the distribution of the sexes according to ages. According thereto, and apart from all other causes already mentioned, a considerable number of women have in such countries no prospect of entering wedded life. The number of unmarried women is even still larger, because a large number of men prefer, for all sorts of reasons, to remain single. What say hereto those superficial folks, who oppose the endeavor of women after a more independent, equal-righted position in life, and who refer them to marriage and domestic life? The blame does not lie with the women that so many of them do not marry; and how matters stand with "conjugal happiness" has been sufficiently depicted.

What becomes of the victims of our social conditions? The resentment of insulted and injured Nature expresses itself in the peculiar facial lines and characteristics whereby so-called old maids, the same as old ascetic bachelors, stamp themselves different from other human beings in all countries and all climates; and it gives testimony of the mighty and harmful effect of suppressed natural love. Nymphomania with women, and numerous kinds of hysteria, have their origin in that source; and also discontent in married life produces attacks of hysteria, and is responsible for barrenness.

Such, in main outlines, is our modern married life and its effects. The conclusion is: Modern marriage is an institution that is closely connected with the existing social condition, and stands or falls with it. But this marriage is in the course of dissolution and decay, exactly as capitalist society itself, – because, as demonstrated under the several heads on the subject of marriage:

1. Relatively, the number of births declines, although population increases on the whole, – showing that the condition of the family deteriorates.

2. Actions for divorce increase in numbers, considerably more than does population, and, in the majority of cases, the plaintiffs are women, although, both economically and socially, they are the greatest sufferers thereunder, – showing that the unfavorable factors, that operate upon marriage, are on the increase, and marriage, accordingly, is dissolving and falling to pieces.

3. Relatively, the number of marriages is on the decline, although population increases, – showing again that marriage, in the eyes of many, no longer answers its social and moral purposes, and is considered worthless, or dangerous.

4. In almost all the countries of civilization there is a disproportion between the number of the sexes, and to the disadvantage of the female sex, and the disproportion is not caused by births – there are, on the average, more boys born than girls, – but is due to unfavorable social and political causes, that lie in the political and economic conditions.

Seeing that all these unnatural conditions, harmful to woman in particular, are grounded in the nature of capitalist society, and grow worse as this social system continues, the same proves itself unable to end the evil and emancipate woman. Another social order is, accordingly, requisite thereto.

CHAPTER III.

PROSTITUTION A NECESSARY SOCIAL INSTITUTION OF THE CAPITALIST WORLD

Marriage presents one side of the sexual life of the capitalist or bourgeois world; prostitution presents the other. Marriage is the obverse, prostitution the reverse of the medal. If men find no satisfaction in wedlock, then they usually seek the same in prostitution. Those men, who, for whatever reason, renounce married life, also usually seek satisfaction in prostitution. To those men, accordingly, who, whether out of their free will or out of compulsion, live in celibacy, as well as to those whom marriage does not offer what was expected of it, conditions are more favorable for the gratification of the sexual impulse than to women.

Man ever has looked upon the use of prostitution as a privilege due him of right. All the harder and severer does he keep guard and pass sentence when a woman, who is no prostitute, commits a "slip." That woman is instinct with the same impulses as man, aye, that at given periods of her life (at menstruation) these impulses assert themselves more vehemently than at others, – that does not trouble him. In virtue of his position as master, he compels her to violently suppress her most powerful impulses, and he conditions both her character in society and her marriage upon her chastity. Nothing illustrates more drastically, and also revoltingly, the dependence of woman upon man than this radically different conception regarding the gratification of the identical natural impulse, and the radically different measure by which it is judged.

To man, circumstances are particularly favorable. Nature has devolved upon woman the consequences of the act of generation: outside of the enjoyment, man has neither trouble nor responsibility. This advantageous position over against woman has promoted that unbridled license in sexual indulgence wherein a considerable part of men distinguish themselves. Seeing, however, that, as has been shown, a hundred causes lie in the way of the legitimate gratification of the sexual instinct, or prevent its full satisfaction, the consequence is frequent gratification, like beasts in the woods.

Prostitution thus becomes a social institution in the capitalist world, the same as the police, standing armies, the Church, and wage-mastership.

Nor is this an exaggeration. We shall prove it.

We have told how the ancient world looked upon prostitution, and considered it necessary, aye, had it organized by the State, as well in Greece as in Rome. What views existed on the subject during the Middle Ages has likewise been described. Even St. Augustine, who, next to St. Paul, must be looked upon as the most important prop of Christendom, and who diligently preached asceticism, could not refrain from exclaiming: "Suppress the public girls, and the violence of passion will knock everything of a heap." The provincial Council of Milan, in 1665, expressed itself in similar sense.

Let us hear the moderns:

Dr. F. S. Huegel says:100 "Advancing civilization will gradually drape prostitution in more pleasing forms, but only with the end of the world will it be wiped off the globe." A bold assertion; yet he who is not able to project himself beyond the capitalist form of society, he who does not realize that society will change so as to arrive at healthy and natural social conditions, – he must agree with Dr. Huegel.

Hence also did Dr. Wichern, the late pious Director of the Rauhen House near Hamburg, Dr. Patton of Lyon, Dr. William Tait of Edinburg, and Dr. Parent-Duchatelet of Paris, celebrated through his investigations of the sexual diseases and prostitution, agree in declaring: "Prostitution is ineradicable because it hangs together with the social institutions," and all of them demanded its regulation by the State. Also Schmoelder writes: "Immorality as a trade has existed at all times and in all places, and, so far as the human eye can see, it will remain a constant companion of the human race."101 Seeing that the authorities cited stand, without exception, upon the ground of the modern social order, the thought occurs to none that, with the aid of another social order, the causes of prostitution, and, consequently, prostitution itself, might disappear; none of them seeks to fathom the causes. Indeed, upon one and another, engaged in this question, the fact at times dawns that the sorry social conditions, which numerous women suffer under, might be the chief reason why so many women sell their bodies; but the thought does not press itself through to its conclusion, to wit, that, therefore, the necessity arises of bringing about other social conditions. Among those who recognize that the economic conditions are the chief cause of prostitution belong Th. Bade, who declares:102 "The causes of the bottomless moral depravity, out of which the prostitute girl is born, lie in the existing social conditions… It is the bourgeois dissolution of the middle classes and of their material existence, particularly of the class of the artisans, only a small fraction of which carries on to-day an independent occupation as a trade." Bade closes his observations, saying: "Want for material existence, that has partly worn out the families of the middle class and will yet wear them out wholly, leads also to the moral ruin of the family, especially of the female sex." In fact, the statistical figures, gathered by the Police Department of Berlin, between 1871-1872, on the extraction of 2,224 enrolled prostitutes, show: