полная версия

полная версияWoman under socialism

Accordingly, a large number of causes are operative in preventing modern married life, in the large majority of instances, from being that which it should be: – a union of two beings of opposite sexes, who, out of mutual love and esteem, wish to belong to each other, and, in the striking sentence of Kant, mean, jointly, to constitute the complete human being. It is, therefore, a suggestion of doubtful value – made even by learned folks, who imagine thereby to dispose of woman's endeavors after emancipation – that she look to domestic duties, to marriage, – to marriage, that our economic conditions are ever turning into a viler caricature, and that answers its purpose ever less!

The advice to woman that she seek her salvation in marriage, this being her real calling, – an advice that is thoughtlessly applauded by the majority of men – sounds like the merest mockery, when both the advisers and their claqueurs do the opposite. Schopenhauer, the philosopher, has of woman only the conception of the philistine. He says: "Woman is not meant for much work. Her characteristicon is not action but suffering. She pays the debt of life with the pains of travail, anxiety for the child, subjection to man. The strongest utterances of life and sentiment are denied her. Her life is meant to be quieter and less important than man's. Woman is destined for nurse and educator of infancy, being herself infant-like, and an infant for life, a sort of intermediate stage between the child and the man, who is the real being… Girls should be trained for domesticity and subjection… Women are the most thorough-paced and incurable Philistines."

In the same spirit as Schopenhauer, who, of course, is greatly quoted, is cast Lombroso and Ferrerro's work, "Woman as a Criminal and a Prostitute." We know no scientific work of equal size – it contains 590 pages – with such a dearth of valid evidence on the theme therein treated. The statistical matter, from which the bold conclusions are drawn, is mostly meager. Often a dozen instances suffice the joint authors to draw the weightiest deductions. The matter that may be considered the most valuable in the work is, typically enough, furnished by a woman, – Dr. Tarnowskaja. The influence of social conditions, of cultural development, is left almost wholly on one side. Everything is judged exclusively from the physiologico-psychologic view-point, while a large quantity of ethnographic items of information on various peoples is woven into the argument, without submitting these items to closer scrutiny. According to the authors, just as with Schopenhauer, woman is a grown child, a liar par excellence, weak of judgment, fickle in love, incapable of any deed truly heroic. They claim the inferiority of woman to man is manifest from a large number of bodily differences. "Love, with woman, is as a rule nothing but a secondary feature of maternity, – all the feelings of attachment that bind woman to man arise, not from sexual impulses, but from the instincts of subjection and resignation, acquired through habits of conformancy." How these "instincts" were acquired and "conformed" themselves, the joint authors fail to inquire into. They would then have had to inquire into the social position of woman in the course of thousands of years, and would have been compelled to find that it is that that made her what she now is. It is true, the joint authors describe partly the enslaved and dependent position of woman among the several peoples and under the several periods of civilization; but as Darwinians, with blinkers to their eyes, they draw all that from physiologic and psychologic, not from social and economic reasons, which affected in strongest manner the physiologic and psychologic development of woman.

The joint authors also touch upon the vanity of woman, and set up the opinion that, among the peoples who stand on a lower stage of civilization, man is the vain sex, as is noticeable to-day in the New Hebrides and Madagascar, among the peoples of the Orinoco, and on many islands of the Polynesian archipelago, as also among a number of African peoples of the South Sea. With peoples standing on a higher plane, however, woman is the vain sex. But why and wherefor? To us the answer seems plain. Among the peoples of a lower civilization, mother-right conditions prevail generally, or have not yet been long overcome. The role that woman there plays raises her above the necessity of seeking for the man, the man seeks her, and to this end, ornaments himself and grows vain. With the people of a higher grade, especially with all the nations of civilization, excepting here and there, not the man seeks the woman, but the woman him. It happens rarely that a woman openly takes the initiative, and offers herself to the man; so-called propriety forbids that. In point of fact, however, the offering is done by the manner of her appearance; by means of the beauty of dress and luxury, that she displays; by the manner in which she ornaments herself, and presents herself, and coquets in society. The excess of women, together with the social necessity of looking upon matrimony as an institute for support, or as an institution through which alone she can satisfy her sexual impulse and gain a standing in society, forces such conduct upon her. Here also, we notice again, it is purely economic and social causes that call forth, one time with man, another with woman, a quality that, until now, it was customary to look upon as wholly independent of social and economic causes. Hence the conclusion is justified, that so soon as society shall arrive at social conditions, under which all dependence of one sex upon another shall have ceased, and both are equally free, ridiculous vanity and the folly of fashion will vanish, just as so many other vices that we consider to-day uneradicable, as supposedly inherent in man. Schopenhauer, as a philosopher, judges woman as one-sidedly as most of our anthropologists and physicians, who see in her only the sexual, never the social, being. Schopenhauer was never married. He, accordingly, has not, on his part, contributed towards having one more woman pay the "debt of life" that he debits woman with. And this brings us to the other side of the medal, which is far from being the handsomer.

Many women do not marry, simply because they cannot. Everybody knows that usage forbids woman to offer herself. She must allow herself to be wooed, i. e., chosen. She herself may not woo. Is there no wooer to be had, then she enters the large army of those poor beings who have missed the purpose of life, and, in view of the lack of safe material foundation, generally fall a prey to want and misery, and but too often to ridicule also. But few know what the discrepancy in numbers between the two sexes is due to; many are ready with the hasty answer: "There are too many girls born." Those who make the claim are wrongly informed, as will be shown. Others, again, who admit the unnaturalness of celibacy, conclude from the fact that women are more numerous than men in most countries of civilization, that polygamy should be allowed. But not only does polygamy do violence to our customs, it, moreover, degrades woman, a circumstance that, of course, does not restrain Schopenhauer, with his underestimation of and contempt for women, from declaring: "For the female sex, as a whole, polygamy is a benefit."

Many men do not marry because they think they cannot support a wife, and the children that may come, according to their station. To support two wives is, however, possible to a small minority only, and among these are many who now have two or more wives, – one legitimate and several illegitimate. These few, privileged by wealth, are not held back by anything from doing what they please. Even in the Orient, where polygamy exists for thousands of years by law and custom, comparatively few men have more than one wife. People talk of the demoralizing influence of Turkish harem life; but the fact is overlooked that this harem life is possible only to an insignificant fraction of the men, and then only in the ruling class, while the majority of the men live in monogamy. In the city of Algiers, there were, at the close of the sixties, out of 18,282 marriages, not less than 17,319 with one wife only; 888 were with two; and only 75 with more than two. Constantinople, the capital of the Turkish Empire, would show no materially different result. Among the country population in the Orient, the proportion is still more pronouncedly in favor of single marriages. In the Orient, exactly as with us, the most important factor in the calculation are the material conditions, and these compel most men to limit themselves to but one wife. If, on the other hand, material conditions were equally favorable to all men, polygamy would still not be practicable, – for want of women. The almost equal number of the two sexes, prevalent under normal conditions, points everywhere to monogamy.

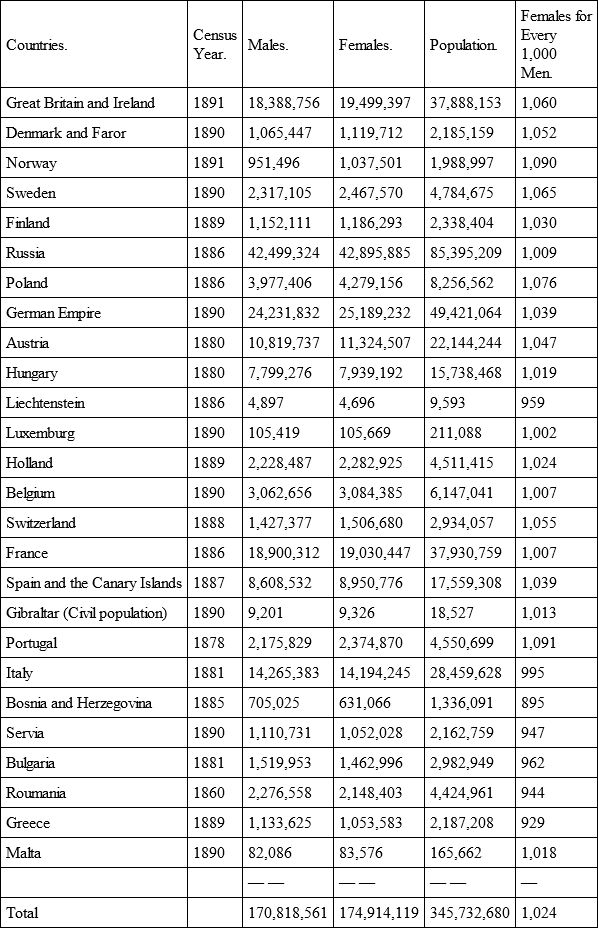

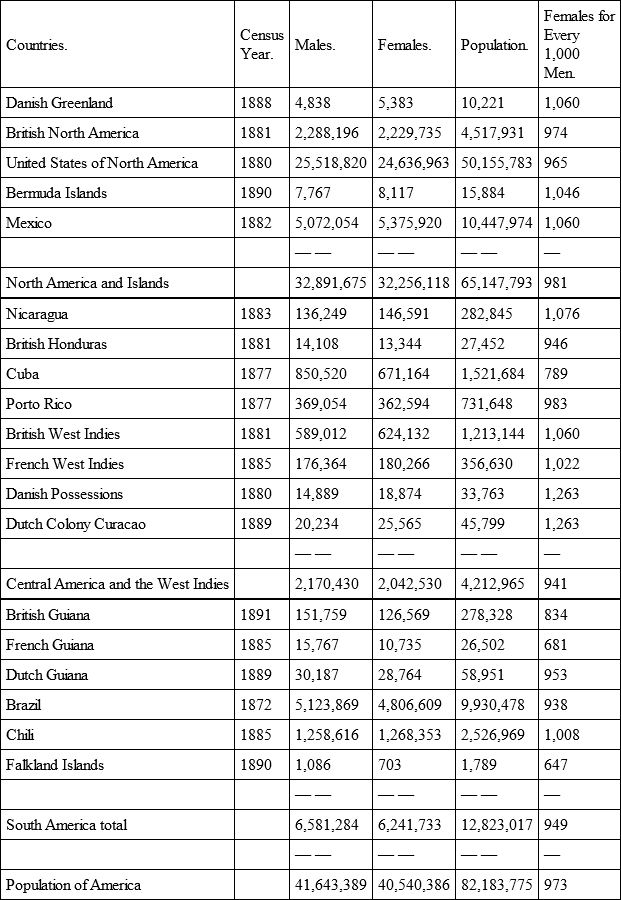

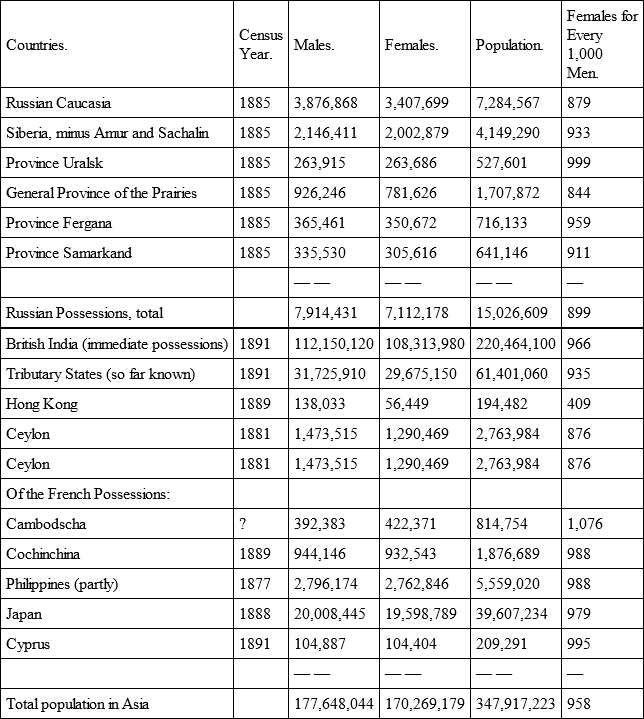

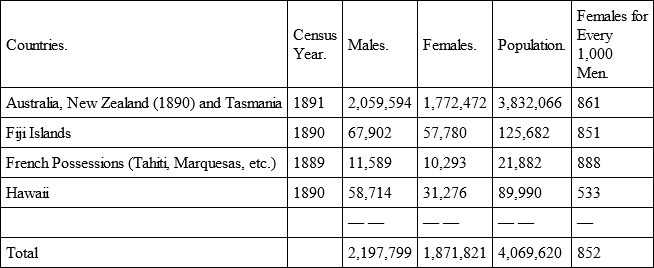

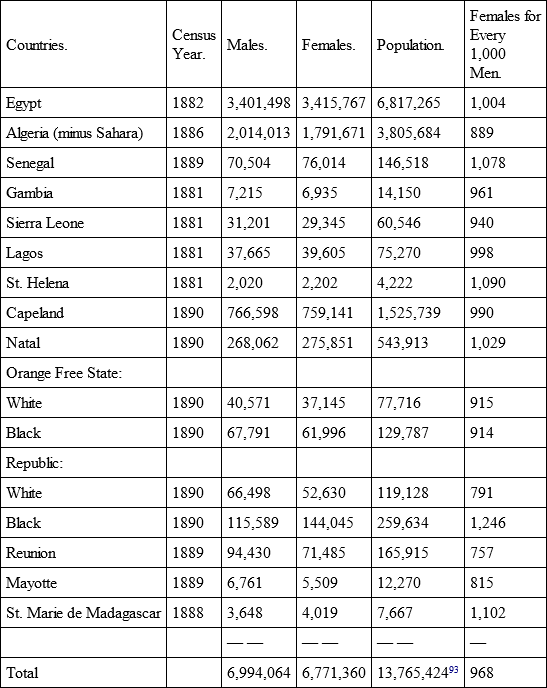

As proof of these statements, we cite the following tables, that Buecher published in an essay.92

In these tables the distinction must be kept in mind between the enumerated and the estimated populations. In so far as the population was enumerated, the fact is expressly stated in the summary for the separate main divisions of the earth. The sexes divide themselves in the population of several divisions and countries as follows:

1. EUROPE.

2. AMERICA.

3. ASIA.

4. AUSTRALIA AND POLYNESIA.

5. AFRICA.

Примечание 193

Probably the result of this presentation will be astonishing to many. With the exception of Europe, where, on an average, there are 1,024 women to every 1,000 men, the reverse is the case everywhere else. If it is further considered that in the foreign divisions of the earth, and even there where actual enumeration was had, information upon the female sex is particularly defective – a fact that must be presumed with regard to all the countries of Mohammedan population, where the figures for the female population are probably below the reality – it stands pat that, apart from a few European nations, the female sex nowhere tangibly exceeds the male. It is otherwise in Europe, the country that interests us most. Here, with the exception of Italy and the southeast territories of Bosnia, Herzegovina, Servia, Bulgaria, Roumania and Greece, the female population is everywhere more strongly represented than the male. Of the large European countries, the disproportion is slightest in France – 1,002 females to every 1,000 males; next in order is Russia, with 1,009 females to every 1,000 males. On the other hand, Portugal, Norway and Poland, with 1,076 females to every 1,000 males, present the strongest disproportion. Next to these stands Great Britain, – 1,060 females to every 1,000 males. Germany and Austria lie in the middle: they have, respectively, 1,039 and 1,047 females to every 1,000 males.

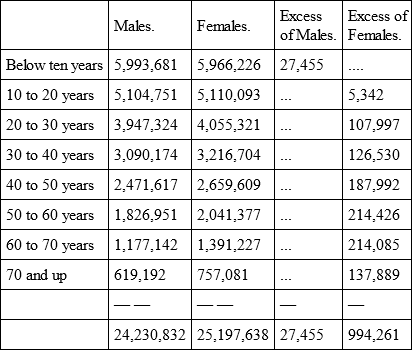

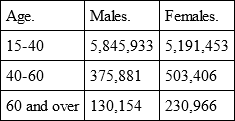

In the German Empire, the excess of the female over the male population, according to the census of December 1, 1890, was 957,400, against 988,376, according to the census of December 1, 1885. A principal cause of this disproportion is emigration, inasmuch as by far more men emigrate than women. This is clearly brought out by the opposite pole of Germany, the North American Union, which has about as large a deficit in women as Germany has a surplus. The United States is the principal country for European emigration, and this is mainly made up of males. A second cause is the larger number of accidents to men than to women in agriculture, the trades, the industries and transportation. Furthermore, there are more males than females temporarily abroad, – merchants, seamen, marines, etc. All this transpires clearly from the figures on the conjugal status. In 1890 there were 8,372,486 married men to 8,398,607 married women in Germany, i. e., 26,121 more of the latter. Another phenomenon, that statistics establish and that weigh heavily in the scales, is that, on an average, women reach a higher age than men: at the more advanced ages there are more women than men. According to the census of 1890 the relation of ages among the two sexes were these:

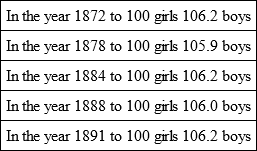

This table shows that, up to the tenth year, the number of boys exceeds that of girls, due merely to the disproportion in births. Everywhere, there are more boys born than girls. In the German Empire, for instance,94 there were born: —

But the male sex dies earlier than the female, and from early childhood more boys die than girls. Accordingly, the table shows that, between the ages of 10 to 20 the female sex exceeds the male.

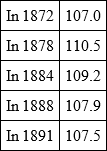

To each 100 females, there died, males: —95

The table shows, furthermore, that at the matrimonial age, proper, between the ages of 20 and 50, the female sex exceeds the male by 422,519, and that at the age from 50 to 70 and above, it exceeds the male by 566,400. A very strong disproportion between the sexes appears, furthermore, among the widowed.

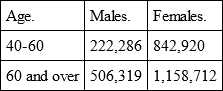

According to the census of 1890, there were: —

Of these widowed people, according to age, there were: —

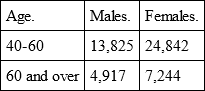

The number of divorced persons was, in 1890: Males, 25,271; females, 49,601. According to age, they were distributed: —

These figures tell us that widows and divorced women are excluded from remarriage, and at the fittest age for matrimony, at that; there being of the age of 15-40, 46,362 widowers and 156,235 widows, 6,519 divorced men and 17,515 divorced women. These figures furnish further proof of the injury that divorce entails to married women.

In 1890, there were unmarried: —96

Accordingly, among the unmarried population between the ages of 15 and 40, the male sex is stronger by 654,480 than the female. This circumstance would seem to be favorable for the latter. But males between the ages of 15 and 21 are, with few exceptions, not in condition to marry. Of that age there were 3,590,622 males to 3,774,025 females. Likewise with the males of the age of 21-25, a large number are not in a position to start a family: we have but to keep in mind the males in the army, students, etc. On the other side, all women of this age period are marriageable. Taking further into consideration that for a great variety of reasons, many men do not marry at all – the number of unmarried males of 40 years of age and over alone amounted to 506,035, to which must be added also the widowed and divorced males, more than two million strong – it follows that the situation of the female sex with regard to marriage is decidedly unfavorable. Accordingly, a large number of women are, under present circumstances, forced to renounce the legitimate gratification of their sexual instincts, while the males seek and find solace in prostitution. The situation would instantaneously change for women with the removal of the obstacles that keep to-day many hundreds of thousands of men from setting up a married home, and from doing justice to their natural instincts in a legitimate manner. For that the existing social system must be upturned.

As already observed, emigration across the seas is, in great part, responsible for the disproportion in the number of the sexes. In the years 1872-1886, on an average, more than 10,000 males left the country in excess of females. For a period of fifteen years, that runs up to 150,000 males, most of them in the very vigor of life. Military duties also drive abroad many young men, and the most vigorous, at that. In 1893, according to the report officially submitted to the Reichstag on the subject of substitutes in the army, 25,851 men were sentenced for emigrating without leave, and 14,522 more cases were under investigation on the same charge. Similar figures recur from year to year. The loss in men that Germany sustains from this unlawful emigration is considerable in the course of a century. Especially strong is emigration during the years that follow upon great wars. That appears from the figures after 1866 and between 1871 and 1874. We sustain, moreover, severe losses in male life from accidents. In the course of the years 1887 to 1892, the number of persons killed in the trades, agriculture, State and municipal undertakings, ran up to 30,568,97 of whom only a small fraction were women. Furthermore, another and considerable number of persons engaged in these occupations are crippled for life by accidents, and are disabled from starting a family; others die early and leave their families behind in want and misery. Great loss in male life is also connected with navigation. In the period between 1882-1891, 1,485 ships were lost on the high seas, whereby 2,436 members of crews – with few exceptions males – and 747 passengers perished.

Once the right appreciation of life is had, society will prevent the large majority of accidents, particularly in navigation; and such appreciation will touch its highest point under Socialist order. In numberless instances human life, or the safety of limb, is sacrificed to misplaced economy on the part of employers, who recoil before any outlay for protection; in many others the tired condition of the workman, or the hurry he must work in, is the cause. Human life is cheap; if one workingman goes to pieces, three others are at hand to take his place.

On the domain of navigation especially, and aided by the difficulty of control, many unpardonable wrongs are committed. Through the revelations made during the seventies by Plimsoll in the British Parliament, the fact has become notorious that many shipowners, yielding to criminal greed, take out high insurances for vessels that are not seaworthy, and unconscionably expose them, together with their crews, to the slightest weather at sea, – all for the sake of the high insurance. These are the so-called "coffin-ships," not unknown in Germany, either. The steamer "Braunschweig," for instance, that sank in 1881 near Helgoland, and belonged to the firm Rocholl & Co., of Bremen, proved to have been put to sea in a wholly unseaworthy condition. The same fate befell, in 1889, the steamer "Leda" of the same firm; hardly out at sea, she went to the bottom. The boat was insured with the Russian Lloyd for 55,000 rubles; the prospect of 8,500 rubles were held out to the captain, if he took her safe to Odessa; and the captain, in turn, paid the pilot the comparatively high wage of 180 rubles a month. The verdict of the Court of Admiralty was that the accident was due to the fact that the "Leda" was unseaworthy and unfit to be taken to Odessa. The license was withdrawn from the captain. According to existing laws, the real guilty parties could not be reached. No year goes by without our Court of Admiralty having to pass upon a larger number of accidents at sea, to the effect that the accident was due to vessels being too old, or too heavily loaded, or in defective condition, or insufficiently equipped; sometimes to several of these causes combined. With a good many of the lost ships, the cause of accident can not be established: they have gone down in midocean, and no survivor remains to tell the tale. Likewise are the coast provisions for the saving of shipwrecked lives both defective and insufficient; they are dependent mainly upon private charity. The case is even more disconsolate along distant and foreign coasts. A commonwealth that makes the promotion of the well-being of all its highest mission will not fail to so improve navigation, and provide it with protective measures that these accidents would be of rare occurrence. But the modern economic system of rapine, that weighs men as it weighs figures, to the end of whacking out the largest possible amount of profit, not infrequently destroys a human life if thereby there be in it but the profit of a dollar. With the change of society in the Socialist sense, immigration, in its present shape, also would drop; the flight from military service would cease; suicide in the Army would be no more.

The picture drawn from our political and economic life shows that woman also is deeply interested therein. Whether the period of military service be shortened or not; whether the Army be increased or not; whether the country pursues a policy of peace or one of war; whether the treatment allotted to the soldier be worthy or unworthy of human beings; and whether as a result thereof the number of suicides and desertions rise or drop; —all of these are questions that concern woman as much as man. Likewise with the economic and industrial conditions and in transportation, in all of which branches the female sex, furthermore, steps from year to year more numerously as working-women. Bad conditions, and unfavorable circumstances injure woman as a social and as a sexual being; favorable conditions and satisfactory circumstances benefit her.

But there are still other momenta that go to make marriage difficult or impossible. A considerable number of men are kept from marriage by the State itself. People pucker up their brows at the celibacy imposed upon Roman Catholic clergymen; but these same people have not a word of condemnation for the much larger number of soldiers who also are condemned thereto. The officers not only require the consent of their superiors, they are also limited in the choice of a wife: the regulation prescribes that she shall have property to a certain, and not insignificant, amount. In this way the Austrian corps of officers, for instance, obtained a social "improvement" at the cost of the female sex. Captains rose by fully 8,000 guilders, if above thirty years of age, while the captains under thirty years of age were thenceforth hard to be had, in no case for a smaller dower than 30,000. "Now a 'Mrs. Captain,'" it was thus reported in the "Koelnische Zeitung" from Vienna, "who until now was often a subject of pity for her female colleagues in the administrative departments, can hold her head higher by a good deal; everybody now knows that she has wherewith to live. Despite the greatly increased requirements of personal excellence, culture and rank, the social status of the Austrian officer was until then rather indefinite, partly because very prominent gentlemen stuck fast to the Emperor's coat pocket; partly because many poor officers could not make a shift to live without humiliation, and many families of poor officers often played a pitiful role. Until then, the officer who wished to marry had, if the thirty-year line was crossed, to qualify in joint property to the amount of 12,000 guilders, or in a 600-guilder side income, and even at this insignificant income, hardly enough for decency, the magistrates often shut their eyes, and granted relief. The new marriage regulations are savagely severe, though the heart break. The captain under thirty must forthwith deposit 30,000 guilders; over thirty years of age, 20,000 guilders; from staff officers up to colonels, 16,000 guilders. Over and above this, only one-fourth of the officers may marry without special grace, while a spotless record and corresponding rank is demanded of the bride. This all holds good for officers of the line and army surgeons. For other military officials with the rank of officer, the new marriage regulations are milder; but for officers of the general staff still severer. The officer who is detailed to the captain of the general staff may not thereafter marry; the actual captain of the staff, if below thirty, is required to give security in 36,000 guilders, and later 24,000 more." In Germany and elsewhere, there are similar regulations. Also the corps of under-officers is subject to hampering regulations with regard to marriage, and require besides the consent of their superior officers. These are very drastic proofs of the purely materialistic conception that the State has of marriage.