полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall, Volume 1: Frontiersman, soldier, lawmaker, 1755-1788

The cost of living in Richmond at the close of the Revolution is shown by numerous entries. Thirty-six bushels of oats cost Marshall three pounds, ten shillings, sixpence. He paid one pound for "one pair stockings"; and one pound, eighteen shillings, sixpence for a hat. In 1783 a tailor charged him one pound, eight shillings, sixpence for "making a Coat." He enters "stockings for P.[olly]575 6 dollars." A stove "Dutch Oven" cost fourteen shillings and eightpence; and "150 bushels coal for self 7-10" (seven pounds, ten shillings).

In October of the year of his marriage he paid six shillings for wine and "For rum £9-15." His entries for household expenditures for these months give an idea of the housekeeping: "Given Polly 6 dollars £4-10-6; … a coffe pot 4/; 1 yd. Gauze 3/6; 2 Sugar boxes £1-7-6; Candlestick &c. 3/6 1 yḍ Linnen for P. 2/6; 2 pieces of bobbin 1/6; Tea pot 3/; Edging 3/6; Sugar pot 1/6; Milk 1/; Thimble 4/2; Irons 9/… Tea 20/."576

The entries in Marshall's Account Book for the first year and a half of his married life are indiscriminately and poorly made, without dates of receipts and expenditures. Then follows a period up to June, 1785, where the days of the month are stated. Then come entries without dates; and later, the dates sometimes are given and sometimes not. Marshall was as negligent in his bookkeeping as he was in his dress. Entries in the notebook show on their face his distaste for such details. The Account Book covers a period of twelve years, from 1783 to 1795.

He was exceedingly miscellaneous in his expenses. On January 14, 1784, he enters as items of outlay: "Whist 30/" and "Whist 12/," "cow £3-12-8" and "poker 6/," "To Parson 30/." This date is jammed in, plainly an afterthought, and no more dates are specified until June 7. Other characteristic entries at this time are, on one day, "Turkeys 12/ Wood 24/ Whist £18"; and on another day, "Beef 26/8 – Backgammon £6." An important entry, undated, is, "Paid the University in the hands of Mr. Tazewell for Colo Marshall as Surveyor of Fayette County 100" (pounds).577

On July 5, 1784, he enters among receipts "to my service in the Assembly 34-4" (pounds and shillings); and among his expenses for June 22 of that year, he enters "lost at Whist £19" and on the 26th, "Colo [James] Monroe & self at the Play 1-10"578 (one pound, ten shillings). A week later the theater again cost him twelve shillings; and on the third he enters an outlay "to one Quarter cask wine 14" (pounds, or about fifty dollars Virginia currency). On the same day appears a curious entry of "to the play 13/" and "Pd for Colo Monroe £16-16." He was lucky at whist this month, for there are two entries during July, "won at whist £10"; and again, "won at whist 4-6" (four pounds, six shillings). He contributes to St. John's Church one pound, eight shillings. During this month their first child was born to the young couple;579 and there are various entries for the immediate expenses of the event amounting to thirteen pounds, four shillings, and threepence. The child was christened August 31 and Marshall enters, "To house for christening 12/ do. 2/6."

The Account Book discloses his diversified generosity. Preacher, horse-race, church, festival, card-game, or "ball" found John Marshall equally sympathetic in his contributions. He was looking for business from all classes in exactly the same way that young lawyers of our own day pursue that object. Also, he was, by nature, extremely sociable and generous. In Marshall's time the preachers bet on horses and were pleasant persons at balls. So it was entirely appropriate that the young Richmond attorney should enter, almost at the same time, "to Mr. Buchanan 5" (pounds)580 and "to my subscription for race £4-4";581 "Saint Taminy 11 Dollars – 3-6"582 (three pounds, six shillings); and still again, "paid my subscription to the ball 20/-1"; and later, "expenses at St. John's [church] 2-3" (pounds and shillings).

Marshall bought several slaves. On July 1, 1784, he enters, "Paid for Ben 90-4"583 (ninety pounds, four shillings). And in August of that year, "paid for two Negroes £30" and "In part for two servants £20." And in September, "Paid for servants £25," and on November 23, "Kate & Evan £63." His next purchase of a slave was three years later, when he enters, May 18, 1787, "Paid for a woman bought in Gloster £55."

Shoeing two horses in 1784 cost Marshall eight shillings; and a hat for his wife cost three pounds. For a bed-tick he paid two pounds, nine shillings. We can get some idea of the price of labor by the following entry: "Pd. Mr. Anderson for plaistering the house £10-2." Since he was still living in his little rented cottage, this entry would signify that it cost him a little more than thirty-five dollars, Virginia currency, to plaster two rooms in Richmond, in 1784. Possibly this might equal from seven to ten dollars in present-day money. He bought his first furniture on credit, it appears, for in the second year of his married life he enters, December "31st Pḍ Mṛ Mason in part for furniture 10" (pounds).

At the end of the year, "Pd balance of my rent 43-13" (pounds and shillings). During 1784, his third year as a lawyer, his fees steadily increased, most of them being about two pounds, though he received an occasional fee of from five to nine pounds. His largest single fee during this year was "From Mr. Stead 1 fee 24" (pounds).

He mixed fun with his business and politics. On February 24, 1784, he writes to James Monroe that public money due the latter could not be secured. "The exertions of the Treasurer & of your other friends have been ineffectual. There is not one shilling in the Treasury & the keeper of it could not borrow one on the faith of the government." Marshall confides to Monroe that he himself is "pressed for money," and adds that Monroe's "old Land Lady Mrs. Shera begins now to be a little clamorous… I shall be obliged I apprehend to negotiate your warrants at last at a discount. I have kept them up this long in hopes of drawing Money for them from the Treasury."

But despite financial embarrassment and the dull season, Marshall was full of the gossip of a convivial young man.

"The excessive cold weather," writes Marshall, "has operated like magic on our youth. They feel the necessity of artificial heat & quite wearied with lying alone, are all treading the broad road to Matrimony. Little Steward (could you believe it?) will be married on Thursday to Kitty Haie & Mr. Dunn will bear off your old acquaintance Miss Shera.

"Tabby Eppes has grown quite fat and buxom, her charms are renovated & to see her & to love her are now synonimous terms. She has within these six weeks seen in her train at least a score of Military & Civil characters. Carrington, Young, Selden, Wright (a merchant), & Foster Webb have alternately bow'd before her & been discarded.

"Carrington 'tis said has drawn off his forces in order to refresh them & has march'd up to Cumberland where he will in all human probability be reinforced with the dignified character of Legislator. Webb has returned to the charge & the many think from their similitude of manners & appetites that they were certainly designed for each other.

"The other Tabby is in high spirits over the success of her antique sister & firmly thinks her time will come next, she looks quite spruce & speaks of Matrimony as of a good which she yet means to experience. Lomax is in his county. Smith is said to be electioneering. Nelson has not yet come to the board. Randolph is here and well… Farewell, I am your J. Marshall."584

Small as were the comforts of the Richmond of that time, the charm, gayety, and hospitality of its inhabitants made life delightful. A young foreigner from Switzerland found it so. Albert Gallatin, who one day was to be so large a factor in American public life, came to Richmond in 1784, when he was twenty-two years old. He found the hospitality of the town with "no parallel anywhere within the circle of my travels… Every one with whom I became acquainted," says Gallatin, "appeared to take an interest in the young stranger. I was only the interpreter of a gentleman, the agent of a foreign house that had a large claim for advances to the State… Every one encouraged me and was disposed to promote my success in life… John Marshall, who, though but a young lawyer in 1783, was almost at the head of the bar in 1786, offered to take me in his office without a fee, and assured me that I would become a distinguished lawyer."585

During his second year in Richmond, Marshall's practice showed a reasonable increase. He did not confine his legal activities to the Capital, for in February we find thirteen fees aggregating thirty-three pounds, twelve shillings, "Recḍ in Fauquier" County. The accounts during this year were fairly well kept, considering that happy-go-lucky John Marshall was the bookkeeper. Even the days of the month for receipts and expenditures are often given. He starts out with active social and public contributions. On January 18, 1785, he enters, "my subscription to Assemblies [balls] 4-4" (pounds and shillings), and "Jan. 29 Annual subscription for Library 1-8" (pound, shillings).

On January 25, 1785, he enters, "laid out in purchasing Certificates 35-4-10." And again, July 4, "Military Certificates pd for self £13-10-2 at 4 for one £3-7-7. Interest for 3 years £2-8 9." A similar entry is made of purchases made for his father; on the margin is written, "pd commissioners."

He made his first purchase of books in January, 1785, to the amount of "£4-12/." He was seized with an uncommon impulse for books this year, it appears. On February 10 he enters, "laid out in books £9-10-6." He bought eight shillings' worth of pamphlets in April. On May 5, Marshall paid "For Mason's Poems" nine shillings. On May 14, "books 17/-8" and May 19, "book 5/6" and "Blackstones Commentaries586 36/," and May 20, "Books 6/." On May 25, there is a curious entry for "Bringing books in stage 25/." On June 24, he purchased "Blair's Lectures" for one pound, ten shillings; and on the 2d of August, a "Book case" cost him six pounds, twelve shillings. Again, on September 8, Marshall's entries show, "books £1-6," and on October 8, "Kaim's Principles of Equity 1-4" (one pound, four shillings). Again in the same month he enters, "books £6-12," and "Spirit of Law" (undoubtedly Montesquieu's essay), twelve shillings.

But, in general, his book-buying was moderate during these formative years as a lawyer. While it is difficult to learn exactly what literature Marshall indulged in, besides novels and poetry, we know that he had "Dionysius Longinus on the Sublime"; the "Works of Nicholas Machiavel," in four volumes; "The History and Proceedings of the House of Lords from the Restoration," in six volumes; the "Life of the Earl of Clarendon, Lord High Chancellor of England"; the "Works of C. Churchill – Poems and Sermons on Lord's Prayer"; and the "Letters of Lord Chesterfield to his son." A curious and entertaining book was a condensed cyclopædia of law and business entitled "Lex Mercatoria Rediviva or The Merchant's Directory," on the title-page of which is written in his early handwriting, "John Marshall Richmond."587 Marshall also had an English translation of "The Orations of Æschines and Demosthenes on the Crown."588

Marshall's wine bills were very moderate for those days, although as heavy as a young lawyer's resources could bear. On January 31, 1785, he bought fourteen shillings' worth of wine; and two and a half months later he paid twenty-six pounds and ten shillings "For Wine"; and the same day, "beer 4d," and the next day, "Gin 30/." On June 14 of the same year he enters, "punch 2/6," the next day, "punch 3/," and on the next day, "punch 6/."589

Early in this year Marshall's father, now in Kentucky and with opulent prospects before him, gave his favorite son eight hundred and twenty-four acres of the best land in Fauquier County.590 So the rising Richmond attorney was in comfortable circumstances. He was becoming a man of substance and property; and this condition was reflected in his contributions to various Richmond social and religious enterprises.

He again contributed two pounds to "Sṭ Taminy's" on May 9, 1785, and the same day paid six pounds, six shillings to "My club at Farmicolas."591 On May 16 he paid thirty shillings for a "Ball" and nine shillings for "music"; and May 25 he enters, "Jockie Club 4-4" (pounds and shillings). On July 5 he spent six shillings more at the "Club"; and the next month he again enters a contribution to "Sṭ Johns [Episcopal Church] £1-16." He was an enthusiastic Mason, as we shall see; and on September 13, 1785, he enters, "pḍ Mason's Ball subscription for 10" (pounds). October 15 he gives eight pounds and four shillings for an "Episcopal Meeting"; and the next month (November 2, 1785) subscribes eighteen shillings "to a ball." And at the end of the year (December 23, 1785) he enters his "Subscription to Richmond Assem. 3" (pounds).

Marshall's practice during his third year at the Richmond bar grew normally. The largest single fee received during this year (1785) was thirty-five pounds, while another fee of twenty pounds, and still another of fourteen pounds, mark the nearest approaches to this high-water mark. He had by now in Richmond two negroes (tithable), two horses, and twelve head of cattle.592

He was elected City Recorder during this year; and it was to the efforts of Marshall, in promoting a lottery for the purpose, that the Masonic Hall was built in the ambitious town.593

The young lawyer had deepened the affection of his wife's family which he had won in Yorktown. Two years after his marriage the first husband of his wife's sister, Eliza, died; and, records the sorrowing young widow, "my Father … dispatched … my darling Brother Marshall to bring me." Again the bereaved Eliza tells of how she was "conducted by my good brother Marshall who lost no time" about this errand of comfort and sympathy.594

February 15, 1786, he enters an expense of twelve pounds "for moving my office" which he had painted in April at a cost of two pounds and seventeen shillings. This year he contributed to festivities and social events as usual. In addition to his subscriptions to balls, assemblies, and clubs, we find that on May 22, 1786, he paid nine shillings for a "Barbecue," and during the next month, "barbecue 7/" and still again, "barbecue 6/." On June 15, he "paid for Wine 7-7-6," and on the 26th, "corporation dinner 2-2-6." In September, 1786, his doctor's bills were very high. On the 22d of that month he paid nearly forty-five pounds for the services of three physicians.595

Among the books purchased was "Blair's sermons" which cost him one pound and four shillings.596 In July he again "Pḍ for Sṭ Taminy's feast 2" (pounds). The expense of traveling is shown by several entries, such as, "Expenses up & down to & from Fauquier 4-12" (four pounds, twelve shillings); and "Expenses going to Gloster &c. 5" (pounds); "expenses going to Wṃṣburg 7" (pounds); and again, "expenses going to and returning from Winchester 15" (pounds); and still again, "expenses going to Wṃṣburg 7" (pounds). On November 19, Marshall enters, "For quarter cask of wine 12-10" (twelve pounds and ten shillings). On this date we find, "To Barber 18" (shillings) – an entry which is as rare as the expenses to the theater are frequent.

He appears to have bought a house during this year (1786) and enters on October 7, 1786, "Pḍ Mr. B. Lewis in part for his house £70 cash & 5£ in an order in favor of James Taylor – 75"; and November 19, 1786, "Paid Mr. B. Lewis in part for house 50" (pounds); and in December he again "Pḍ Mr. Lewis in part for house 27-4" (twenty-seven pounds, four shillings); and (November 19) "Pḍ Mr. Lewis 16" (pounds); and on the 28th, "Paid Mr. Lewis in full 26-17-1 1/4."

In 1786, the Legislature elected Edmund Randolph Governor; and, on November 10, 1786, Randolph advertised that "The General Assembly having appointed me to an office incompatible with the further pursuit of my profession, I beg leave to inform my clients that John Marshall Esq. will succeed to my business in General &c."597

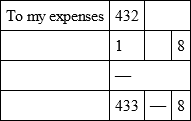

At the end of this year, for the first time, Marshall adds up his receipts and expenditures, as follows: "Received in the Year 1786 according to the foregoing accounts 508-4-10." And on the opposite page he enters598—

In 1787 Marshall kept his accounts in better fashion. He employed a housekeeper in April, Mrs. Marshall being unable to attend to domestic duties; and from February, 1787, until May of the following year he enters during each month, "Betsy Mumkins 16/." The usual expenditures were made during this year, and while Marshall neglects to summarize his income and outlay, his practice was still growing, although slowly. On December 3, 1787, his second child was born.599

In January of 1787 occurred the devastating Richmond fire which destroyed much of the little city;600 and on February 7, Marshall enters among his expenses, "To my subscription to the sufferers by fire 21" (pounds).

Marshall's name first appears in the reports of the cases decided by the Virginia Court of Appeals in 1786. In May of that year the court handed down its opinion in Hite et al. vs. Fairfax et al.601 It involved not only the lands directly in controversy, but also the validity of the entire Fairfax title and indirectly that of a great deal of other land in Virginia. Baker, who appears to have been the principal attorney for the Fairfax claimants, declared that one of the contentions of the appellants "would destroy every title in the Commonwealth." The case was argued for the State by Edmund Randolph, Attorney-General, and by John Taylor (probably of Caroline). Marshall, supporting Baker, acted as attorney for "such of the tenants as were citizens of Virginia." The argument consumed three days, May 3 to 5 inclusive.602

Marshall made an elaborate argument, and since it is the first of his recorded utterances, it is important as showing his quality of mind and legal methods at that early period of his career. Marshall was a little more than thirty years old and had been practicing law in Richmond for about three years.

The most striking features of his argument are his vision and foresight. It is plain that he was acutely conscious, too, that it was more important to the settlers who derived their holdings from Lord Fairfax to have the long-disputed title settled than it was to win as to the particular lands directly in controversy. Indeed, upon a close study of the complicated records in the case, it would seem that Joist Hite's claim could not, by any possibility, have been defeated. For, although the lands claimed by him, and others after him, clearly were within the proprietary of Lord Fairfax, yet they had been granted to Hite by the King in Council, and confirmed by the Crown; Lord Fairfax had agreed with the Crown to confirm them on his part; he or his agents had promised Hite that, if the latter would remain on the land with his settlers, Fairfax would execute the proper conveyances to him, and Fairfax also made other guarantees to Hite.

But it was just as clear that, outside of the lands immediately in controversy, Lord Fairfax's title, from a strictly legal point of view, was beyond dispute except as to the effect of the sequestration laws.603 It was assailed, however, through suggestion at least, both by Attorney-General Randolph and by Mr. Taylor. There was, at this time, a strong popular movement on foot in Virginia to devise some means for destroying the whole Fairfax title to the Northern Neck. Indeed, the reckless royal bounty from which this enormous estate sprang had been resented bitterly by the Virginia settlers from the very beginning;604 the people never admitted the justice and morality of the Fairfax grant. Also, at this particular period, there was an epidemic of debt repudiation, evasion of contracts and other obligations, and assailing of titles.605

So, while Baker, the senior Fairfax lawyer, referred but briefly to the validity of the Fairfax title and devoted practically the whole of his argument to the lands involved in the case then before the court, Marshall, on the other hand, made the central question of the validity of the whole Fairfax title the dominant note of his argument. Thus he showed, in his first reported legal address, his most striking characteristic of going directly to the heart of any subject.

Briefly reported as is his argument in Hite vs. Fairfax, the qualities of far-sightedness and simple reasoning, are almost as plain as in the work of his riper years: —

"From a bare perusal of the papers in the cause," said Marshall, "I should never have apprehended that it would be necessary to defend the title of Lord Fairfax to the Northern Neck. The long and quiet possession of himself and his predecessors; the acquiescence of the country; the several grants of the crown, together with the various acts of assembly recognizing, and in the most explicit terms admitting his right, seemed to have fixed it on a foundation, not only not to be shaken, but even not to be attempted to be shaken.

"I had conceived that it was not more certain, that there was such a tract of country as the Northern Neck, than that Lord Fairfax was the proprietor of it. And if his title be really unimpeachable, to what purpose are his predecessors criminated, and the patents they obtained attacked? What object is to be effected by it? Not, surely, the destruction of the grant; for gentlemen cannot suppose, that a grant made by the crown to the ancestor for services rendered, or even for affection, can be invalidated in the hands of the heir because those services and affection are forgotten; or because the thing granted has, from causes which must have been foreseen, become more valuable than when it was given. And if it could not be invalidated in the hands of the heir, much less can it be in the hands of a purchaser.

"Lord Fairfax either was, or was not, entitled to the territory; if he was, then it matters not whether the gentlemen themselves, or any others, would or would not have made the grant, or may now think proper to denounce it as a wise, or impolitic, measure; for still the title must prevail; if he was not entitled, then why was the present bill filed; or what can the court decree upon it? For if he had no title, he could convey none, and the court would never have directed him to make the attempt.

"In short, if the title was not in him, it must have been in the crown; and, from that quarter, relief must have been sought. The very filing of the bill, therefore, was an admission of the title, and the appellants, by prosecuting it, still continue to admit it…

"It [the boundary] is, however, no longer a question; for it has been decided, and decided by that tribunal which has the power of determining it. That decision did not create or extend Lord Fairfax's right, but determined what the right originally was. The bounds of many patents are doubtful; the extent of many titles uncertain; but when a decision is once made on them, it removes the doubt, and ascertains what the original boundaries were. If this be a principle universally acknowledged, what can destroy its application to the case before the court?"

The remainder of Marshall's argument concerns the particular dispute between the parties. This, of course, is technical; but two paragraphs may be quoted illustrating what, even in the day of Henry and Campbell, Wickham and Randolph, men called "Marshall's eloquence."

"They dilate," exclaimed Marshall, "upon their hardships as first settlers; their merit in promoting the population of the country; and their claims as purchasers without notice. Let each of these be examined.

"Those who explore and settle new countries are generally bold, hardy, and adventurous men, whose minds, as well as bodies, are fitted to encounter danger and fatigue; their object is the acquisition of property, and they generally succeed.

"None will say that the complainants have failed; and, if their hardships and danger have any weight in the cause, the defendants shared in them, and have equal claim to countenance; for they, too, with humbler views and less extensive prospects, 'have explored, bled for and settled a, 'till then, uncultivated desert.'"606

Hite won in this particular case; but, thanks to Marshall's argument, the court's decision did not attack the general Fairfax title. So it was that Marshall's earliest effort at the bar, in a case of any magnitude, was in defense of the title to that estate of which, a few years later, he was to become a principal owner.607 Indeed, both he and his father were interested even then; for their lands in Fauquier County were derived from or through Fairfax.