полная версия

полная версияA Statistical Inquiry Into the Nature and Treatment of Epilepsy

1. Medicinal doses of the bromides produce in healthy persons a general diminution of nervous energy. They act as a sedative, and thus dispose to repose and sleep. If they are excessive in quantity and long continued, especially in those susceptible to their action, a series of toxic effects are produced. Various organs and functions of the body are influenced, and the results of the poison may be briefly summed up as follows: – The intellectual faculties are blunted, the memory is impaired, the ideas confused, the patient is dull, stupid, and apathetic, and has a constant tendency to somnolence. The speech is impeded and slow, and the tongue is tremulous. The special senses are weakened. The body, as a whole, is infirm, the limbs feeble, and the gait staggering and incoördinated. The reflex excitability is lowered and the sensibility diminished. The sexual powers are impaired or abolished. These symptoms may be present in a variety of degrees, and in advanced cases even imbecility or paralysis may ensue. The mucous membranes become dry and insensitive, especially those of the fauces. This is attended with various functional disorders, such as nausea, flatulence, gastric catarrh, diarrhœa, &c. The skin is pale, and the extremities are cold. The action of the heart is slow and weak. The respiration is shallow, hurried, and imperfect. The integument is frequently covered with an acne-like eruption. To these symptoms may be added a general cachexia. All these abnormal conditions, as a rule, disappear when the consumption of the poison is arrested.

2. Although some persons, suffering from epileptic seizures, are, in the intervals, of sound mind and body, in many the inter-paroxysmal state is characterized by certain symptoms peculiar to this condition, and independent of any form of treatment. These vary from the slightest departures from health to the most serious mental and physical disease. The general health is frequently unsatisfactory; the functions of the body being impaired in vigour, the digestion is weak, and the circulation feeble. The entire nervous system is in an unstable condition, the patient being at one time irritable and excitable, and at another depressed and despondent. There is a very common condition of so-called "nervousness" which is accompanied by headache, pains, tremors, and a variety of other subjective phenomena. The mental powers are enfeebled, the memory defective, and these intellectual alterations may exist in any degree, even to permanent and intractable forms of insanity. The physical conditions may also be changed, the nutrition of the tissues is often imperfect, the skin is pale, the muscles flabby, and the motor powers generally enfeebled, all of which may also present different degrees of severity, so as to culminate in actual paralysis.

Admitting, then, that the prolonged and excessive administration of the bromides causes a series of abnormal symptoms in the healthy individual, affecting mainly the general nutrition, the mental faculties, and the sensory and motor functions, and also that the epileptic state is itself frequently accompanied by impairment of innervation of a somewhat analogous nature, it follows that when the drug is given for the relief of the disease, care must be taken not to confound the two series of phenomena with one another. With this precaution in view, granting that the therapeutic agent beneficially controls and suppresses the convulsive seizures, we proceed to discuss whether in so doing it in any way injuriously influences the constitution of the patient. To answer this question has been found by no means easy. Comparatively few physicians have opportunities of observing cases of epilepsy in sufficient numbers to form substantial conclusions on the subject. Even in favoured circumstances it is difficult, especially in hospital practice, to ensure the regular attendance of the patient or to keep him sufficiently long under observation. The study and the recording of the facts, moreover, demand an expenditure of much time and labour. These, added to the sources of fallacy already enumerated, render the inquiry a complicated one; but it is believed that an approximation to the truth may be arrived at by the following method of investigation.

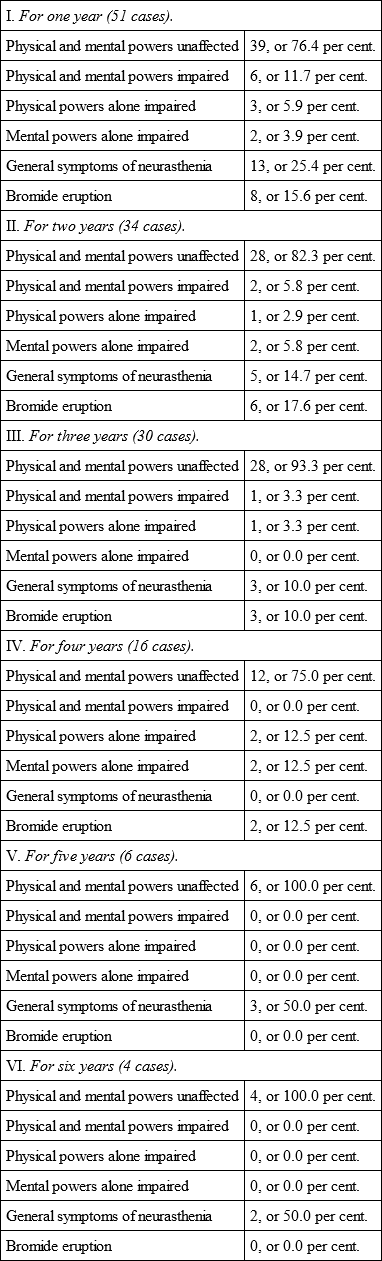

A large number of cases of epilepsy form the basis of the statistics, the great majority of whom are adults. No selection of any kind is made, and all are admitted irrespective of the cause, nature, or severity of the disease. The particulars of each having been noted, treatment by the bromides was instituted, the minimum dose being one drachm and a half daily,7 which, if necessary, was further increased in quantity. The progress of the patient was observed at frequent and regular intervals, and if the attendance was irregular the case was excluded from the present inquiry. The result of this proceeding is an aggregate of 141 cases, all of whom have been constantly under the influence of the drug for periods varying from one to six years. These are arranged in groups according to the length of time they were under treatment. The immense mass of details thus collected, added to the varied circumstances connected with individual cases, render it impossible, in constructing a summary of the whole, to do more than select certain prominent features of interest for examination and demonstration. These in tabular form are as follows: —

Tables showing the effects of the continuous administration of the bromides in the epileptic state, in 141 cases, the condition being ascertained at the end of each period.

In the construction of the details of the above tables, care has been taken as far as possible to distinguish between the effects of the remedy and the symptoms associated with the disease, although this has not been always easy to accomplish. It has, however, been approximately arrived at by a careful study of the patient's health before treatment, as compared with his subsequent state, and those symptoms only were considered toxic which were superadded to pre-existing abnormal conditions. A general analysis of the facts thus collected shows that in the majority of cases the physical and mental powers do not appear to be injuriously affected by the prolonged use of the bromides. It is not asserted that all the individuals placed under this section were necessarily sound in mind and body. In many instances the functions of these were impaired, but there was no evidence to indicate that this was the result of the medicine taken; on the contrary, there was every reason to believe that the symptoms thus displayed were a part of the original disease, and had existed prior to treatment.

In a very small percentage of cases were both physical and mental powers unfavourably modified as a direct consequence of the use of the bromides, and even in these there is no absolute certainty that the drugs were entirely responsible for the symptoms, seeing that these might be attributed to the epileptic condition as well as to the toxic effects of the remedy. They are considered under this category, as the abnormal phenomena appeared to be augmented after treatment and improved on its temporary cessation. They mainly consisted, on the one hand, of loss of memory, dulness of apprehension, apathy, somnolence, depression of spirits, and mental debility; and on the other, of bodily languor, muscular fatigue, and general physical weakness. In no case did any of these symptoms attain an excessive or prominent position. The same conditions apply when the physical or mental powers were impaired independently of one another.

Under the heading of general phenomena of neurasthenia is included a series of indefinite subjective neurotic symptoms, without intellectual or bodily deficiencies, in which the patient complained of headache, neuralgic pains, tremors, of being easily startled and frightened, with that general instability of the nervous system to which the term neurasthenia has been given. This condition is extremely common in the epileptic, and is frequently relieved by treatment. At other times it remains persistent in spite of all medicaments, and the numbers in the tables indicate those cases conspicuous by their continuance under the use of the bromides. Those attacked by the follicular rash are seen at first to be about 16 per cent., but gradually diminishing in number as the treatment becomes chronic, and finally disappearing altogether.

In addition to the points referred to in the tables, other questions have been investigated, although on a smaller scale. For example, in persons who have been under the influence of the bromides for many years, the skin and tendon reflex action remain intact, and I have never seen a case in which the knee-jerk or plantar phenomena were absent. In only one case was the general sensibility of the skin perceptibly diminished. With regard to the effects on the sexual powers, I have not sufficient data upon which to found positive rules. This statement, however, may be made, that the prolonged use of even large doses of this drug does not of necessity abolish or even sensibly impair this function, although, no doubt, it usually does so. On examining the respiration and pulse, I have never been able to detect any characteristic abnormality.

I might record many cases in detail to prove the seemingly innocuous nature of even large and long-continued doses of the bromides in epilepsy. I shall, however, as an illustration, limit myself to a few notes on the four cases which compose Table VI., all of whom were continuously under the influence of the drugs for a period of not less than six years.

Case 1. – Louisa C – , aged twenty-nine, has suffered from epileptic attacks for fourteen years. Prior to treatment she had three or four every week, of a severe character, consisting of loss of consciousness, general convulsions, biting of the tongue, &c. She has always been a delicate person, with a tendency to great nervousness, but otherwise intelligent, and in fair general health. She has taken one and a half drachms of bromide of potassium daily regularly for the last six years, and states that if she attempts to discontinue the medicine all her symptoms are aggravated. At present the patient is a robust, healthy-looking woman, of fair intelligence and good spirits. Her memory is deficient. Her physical powers are vigorous, and she earns her living as a bookbinder. She has an attack about once a month, and with the exception of this and occasional headaches and nervousness, she professes and seems to be in excellent general health. Sensibility, the knee-jerk, and plantar phenomena are normal. The fauces are insensitive, and their reflex is abolished. Pulse 60, normal. The circulation, respiration, and other functions are healthy. No traces of bromism.

Case 2. – Charles P – , aged thirty-five, has suffered from epileptic attacks of a severe convulsive character for eighteen years, having had one about once a month. Prior to treatment, although his memory was defective, his intelligence and general health were good. For the last six years he has regularly taken the bromides of potassium and ammonium (one drachm and a half) daily. At present he still continues to have an attack about once a month. His mental and physical conditions are the same as before. He appears perfectly intelligent. His strength is robust, so that he does his ordinary work as a pianoforte maker. Pulse 74, of good strength. All the reflexes are normal, except that of the fauces, which is abolished. Sensibility of the skin to touch slightly diminished. The sexual functions are normal. No symptoms of bromism.

Case 3. – Matilda W – , aged thirty-one, has suffered from epilepsia gravior and mitior for twenty-two years, having of the former about one seizure in three months, and of the latter ten or twelve a day. She has always been a delicate woman, suffering from headaches, general irritability, and nervousness. She is, however, perfectly intelligent. For six years past she has taken regularly the bromides of potassium and ammonium, one drachm of each daily. She has not had an attack of epilepsy major for a year, and of epilepsy mitior has now only about one a week. Although anæmic, her general health is good, and she is able to do a full day's work as a washer-woman. Intellectually she is quite sound, but has a treacherous memory, and is very nervous. Sensibility, reflex acts, &c., are as in the other cases.

Case 4. – Lucy D – , aged twenty-two, has suffered from epilepsy major for eight years. Formerly had about one attack a week. Has always been a delicate girl, but her general health and mental condition have been normal. For the last six years she has regularly taken one drachm and a half of the bromides daily (potassium and ammonium in equal parts). She has had only three attacks during the past year. Her general health is excellent. She is robust and active, and takes her full share in domestic work. She is well educated, intelligent, with good memory and spirits, and has no tendency to depression or somnolence. The sensibility, reflex acts, and other functions are as in the other cases.

In these four cases it has been ascertained that the patients were constantly under the influence of large doses of the bromides for a period of not less than six years, and practically without intermission. During this period not only were the frequency and severity of the convulsive attacks beneficially modified, but there was no evidence to show that the physical or mental condition had been in any way impaired. It is further to be observed that these as well as many others of those constituting the later tables, are examples of unusually long-standing and severe forms of epilepsy, as evidenced by the fact of their chronic and intractable nature even under treatment. Notwithstanding the incompleteness of their recovery, these individuals have voluntarily, and often at great inconvenience and expense, persevered in the use of the remedy, which is a fair indication they derived some substantial benefit from it. The examples before us, one and all, declared they have found by experience that when they have attempted, even for brief periods, to discontinue the medicine their symptoms have all become aggravated. As a result the attacks increase in severity and number, the headaches return, the nervousness augments, and they are unable to perform either mental or bodily exertion. These sufferings, it is maintained, are greatly modified by the bromides, as under their influence epileptics may perform their daily work, when without them they are comparatively useless. It would be easy to multiply individual cases supporting the same general principles. One more instance only need be particularized – namely, that of a man aged thirty, who has suffered from epilepsy from infancy, and who for the last five years has taken four and a half drachms of the bromides daily —i. e., during that time he has consumed upwards of eighty pounds of the drug. Although a delicate person and intellectually weak, his friends state that during those years he has been more healthy and robust in mind and body than at any other period of his life. And these statements were confirmed by other testimony.

While attempting to estimate the therapeutic value of the bromides from a statistical aspect, one likely source of fallacy must not be overlooked. Most patients, and especially those attending hospitals, are difficult to keep under observation for long periods, more particularly if the progress of the case is unsatisfactory. In this way we may lose sight of those who do not benefit by treatment or who are injured by it. Although it is difficult to estimate these with accuracy, a certain rebatement must always be made on this count in computing results. At the same time we have in the present inquiry positive evidence, in a considerable number of cases, of the innocuous and beneficial nature of the drug, against the negative possibility only of its disadvantages. Of the 141 cases under notice, I only know of three who have died, and all of then of phthisis pulmonalis. The relations existing between the mortality and cause of death on the one hand, and the disease and treatment on the other, the paucity of the data do not permit us to determine.

A further study of the tables would also seem to show that while the beneficial action of the bromides remains permanent, the deleterious effects diminish the longer the drug has been taken. This is doubtless due, as in the case of most poisons, to the system becoming habituated to its use. It has often been observed that the most marked effects of bromism have appeared at the beginning of treatment, and that the eruption, the physical and mental depression, &c., subsequently disappeared, although the medicine was persevered in. Those who have been under its influence for some years rarely present any symptoms directly attributable to the toxic effects of the bromides; and if abnormal conditions do exist, these are the sequelæ of the malady, and not the results of treatment, as shown by the fact that when the last is suspended, the original sufferings are augmented.

It may be suggested that a prolonged use of the bromides becomes, as in the case of opium, a habit. There is, however, a marked distinction between the two. Opium-smoking is a vice not only deleterious in itself, but one indulged in merely to satisfy a morbid craving. The bromides, on the other hand, are less hurtful in their effects, and are taken to avert the symptoms of a distressing and terrible malady. Assuming, then, that their consumption becomes a necessity, if it can be shown that the results are not serious, while the evils they avert are important, the habit acquired may be looked upon as a justifiable one.

A general review of all these circumstances seems to render it probable that the epileptic constitution is more tolerant of the toxic effects of the bromides than the healthy system. The most severe effects of bromism occur in those who are not the victims of this malady, in whom, as seen by the foregoing facts, they are not common. Theoretically this may be plausibly explained by the reasonable assumption that, as in epilepsy the entire nervous apparatus is in a state of reflex hyper-excitability, the sedative and poisonous effects of the bromides do not produce the depressing or toxic actions they would do in a more stable organization. Whatever the reason may be, the fact is that the symptoms of bromism are not so severe in the epileptic as they are in otherwise healthy subjects.

Finally, the important question arises, Does a prolonged use of the bromides tend towards the eradication of the disease itself and the ultimate cure of the epileptic state? On this point I have no personal statistical evidence to offer, nor am I aware of the existence of any sufficiently scientific series of data to settle the question. Without there being actual demonstration of the fact, there is every reason to believe that such a supposition is possible. Clinical observation has determined that the larger the number of convulsive seizures the greater is the tendency to the production of others, and the more readily are they caused. Such is the abnormal reflex hyper-excitability of the nervous system of the epileptic that the irritative effects of one attack seem directly to pre-dispose to the occurrence of a second; so that the larger the number of explosions of nerve instability which actually take place, the more there are likely to follow. Could such seizures be kept in check, this cause of the production of convulsions at least would be diminished, the liability for them to break out as a result of trifling external stimuli would be lessened, and the long-continued absence of this source of irritation might by the repose and favourable circumstances thus obtained, encourage a healthy transformation of tissue. Now, it has already been pointed out that in 12.1 per cent. of epileptics the attacks were completely arrested during the entire time the drugs were being administered, and that in a much larger percentage they were greatly modified in number and severity. It has been further shown that the remedies themselves, even when in use for long periods, are in themselves practically innocuous, while at the same time they continue to maintain their beneficial effects on the attacks. It therefore follows that a sufficiently prolonged treatment might in a certain number of cases be succeeded by permanent curative results. The chief impediment to arriving at trustworthy conclusions on this subject has been the length of time necessary to judge of lasting benefits, and the difficulty of keeping patients sufficiently long under observation. Another has been the objection raised to the method of treatment on the grounds of a visionary suspicion that the toxic effects of the drug were of a dangerous nature, and their results more distressing than the diseases for which they were given. So far as my experience has extended, I believe this fear has not been warranted by facts.

June, 1884.1

Reprinted from the "British Medical Journal" of March 15 & 22, 1879.

2

Reprinted from the "Edinburgh Medical Journal" for February and March, 1881.

3

For an extended experience, see the next paper.

4

Reprinted from the "Lancet" of May 17th and 24th, 1884.

5

See Article II.

6

Vide preceding paper.

7

The usual prescription contained the bromides of potassium and ammonium, fifteen grains of each for a dose.