полная версия

полная версияA Statistical Inquiry Into the Nature and Treatment of Epilepsy

℞ Pot. bromid., gr. xv.

Ammon. bromid., gr. xv.

Sp. ammon. aromat., m. xx.

Infus. quassia, ad ℥j

M. Ft. haust. ter die, sumendus.

According to the age of the patient so must the dose be regulated; at the same time, children bear the drug very well. The average quantity to begin with for a child of ten or twelve years has been twenty grains thrice daily.

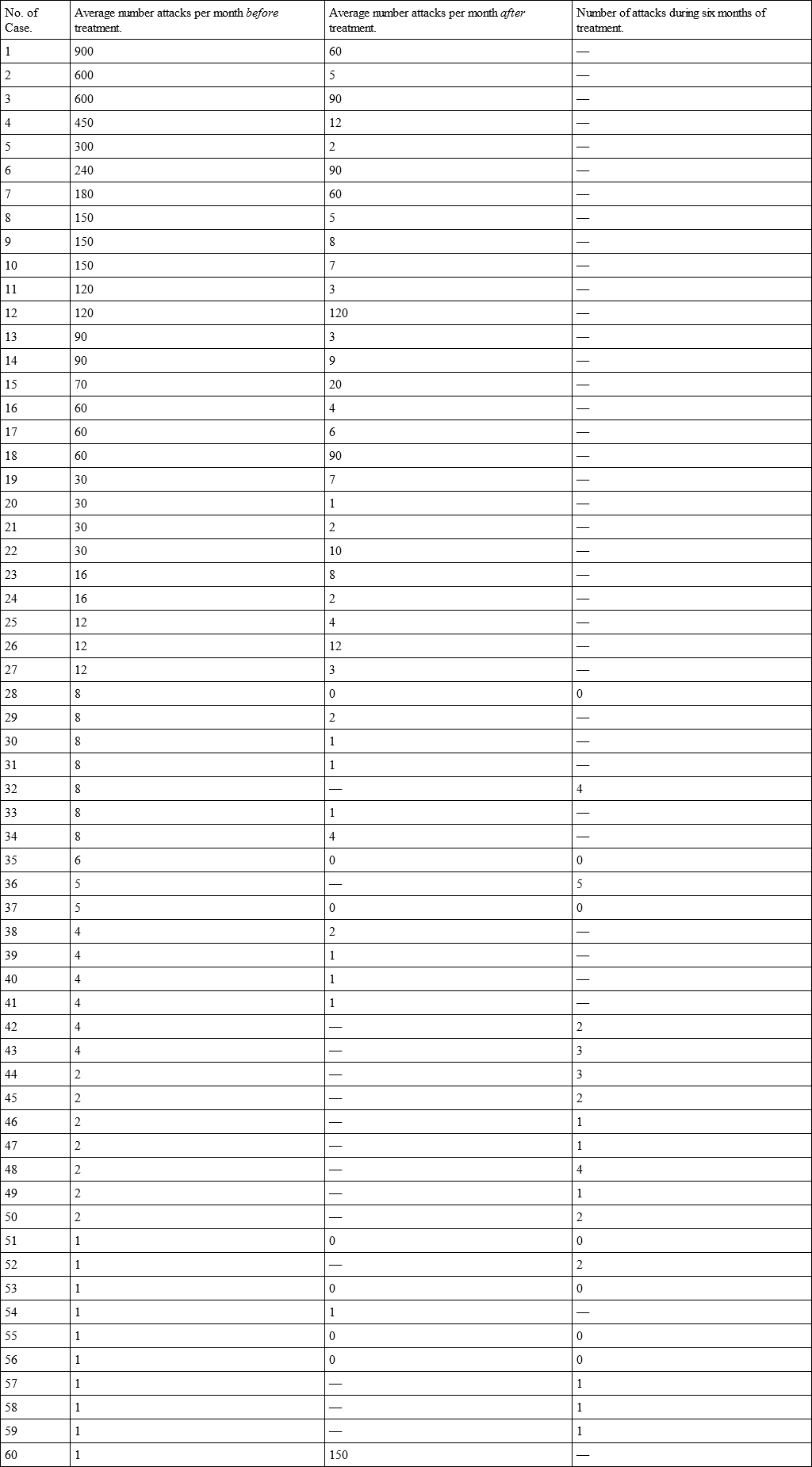

In this manner I have personally treated about two hundred cases, and in all of these most careful records have been kept, not only of their past history, present condition, etc., but of their progress during observation. All these, however, are not available for the present inquiry. It is necessary in order to judge of the true effect of a drug in epilepsy that the patient should be under its influence continuously for a certain period of time. Now, a large number of patients, especially amongst the working classes, cannot or will not be induced to persevere in the prolonged treatment necessary in so chronic a disease. They either weary of the monotony of drinking physic, especially if, as is often the case, they are relieved for the time, or other circumstances prevent their carrying out the regimen to its full extent. The minimum time I have fixed as a test for judging the influence of the bromides on epileptic seizures is six months, and the maximum in my own experience extends to four years.3 All other cases have been eliminated. I have arranged this experience in the form of tables for reference, in which will be seen at a glance —1st, the average number of attacks per month in each case prior to treatment; 2nd, the average number of attacks per month after treatment; and 3rd, in the event of these being fewer than one seizure per month, the total number during the last six months of treatment.

Table I. —Sixty Cases of Epilepsy, showing Results of Treatment by the Bromides during a Period of from 6 Months to 1 Year.

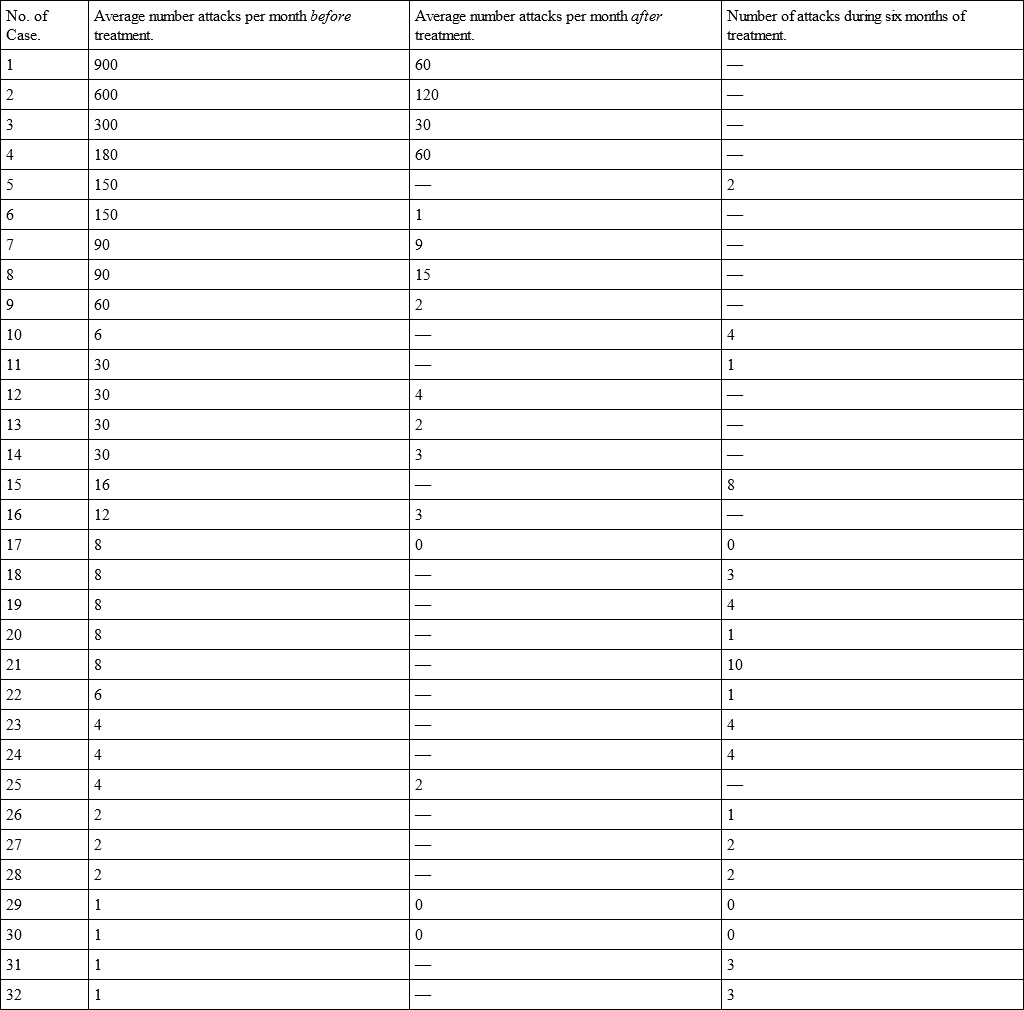

Table II. —Thirty-two Cases of Epilepsy, showing Results of Treatment by the Bromides during a period of from 1 to 2 Years.

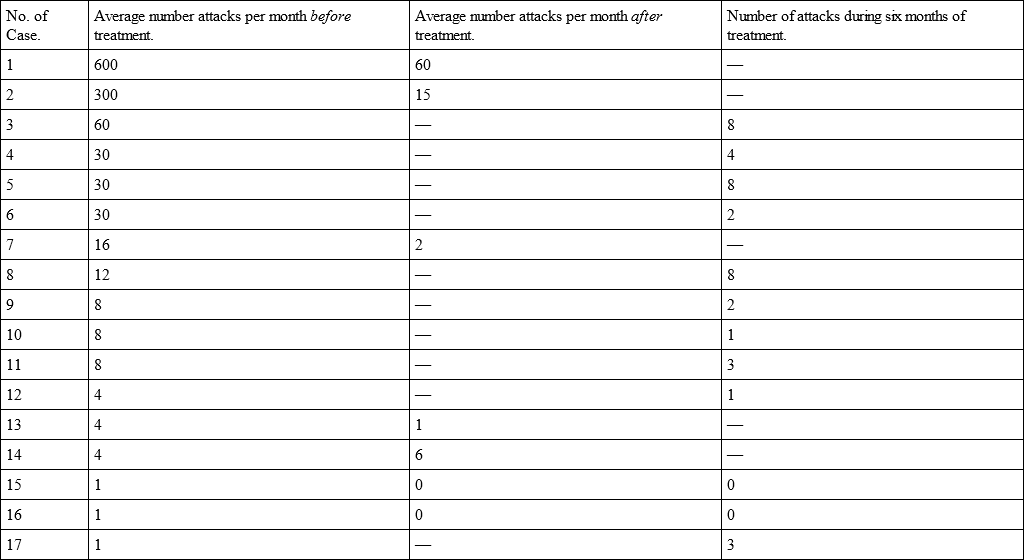

Table III. —Seventeen Cases of Epilepsy, showing Results of Treatment by the Bromides during a Period of from Two to Three Years.

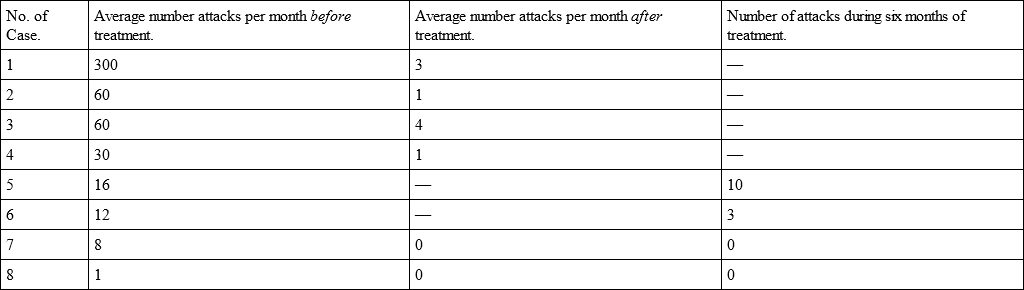

Table IV. —Eight Cases of Epilepsy, showing the Results of Treatment by the Bromides during a period of from Three to Four Years.

These four tables consist of all the characteristic cases of epilepsy which came under notice, without selection of any kind, all being included, no matter what their form or severity, their age, complication with organic disease, etc. In analyzing this miscellaneous series, the chief fact to be noticed, whether the period of treatment has been limited to six months or extended to four years, is the remarkable effect of treatment upon the number of the epileptic seizures. Of the total 117 cases, in 14, or about 12.1 per cent., the attacks were entirely arrested during the whole period of treatment. In 97, or about 83.3 per cent., the monthly number of seizures was diminished. In 3, or about 2.3 per cent., there was no change either for better or worse; and in 3, or about 2.3 per cent., the attacks were more frequent after treatment.

With regard to the fourteen cases which were free from attacks during treatment, it cannot, of course, be maintained that all of these were cured in the strict sense of the term. It is probable that if any of them discontinued the medicine the seizures would return. Still, the results are such as to encourage a hope that if the bromides are persevered with, and the attacks arrested for a sufficiently long period, a permanent result might be anticipated. Even should no such ultimate object be realized, it is obvious that an agent which can, during its administration, completely cut short the distressing epileptic paroxysms, without injuriously affecting the mental or bodily health, is of immense importance. Take, for example, cases 7 and 8 of Table IV., where, prior to treatment, in the one case eight fits a month, and in the other one, were completely arrested during a period of nearly four years. The experience of physicians agrees in considering that the danger of epilepsy, both to mind and body, is in great part directly proportionate to the severity of its symptoms. If these latter can be completely arrested, even should we be compelled to continue the treatment, if this is without injury to the patient, it is as close an approach to cure as we can ever expect to arrive at by therapeutic means. The permanent nature of the improvement, and the possibility of subsequent discontinuance of the bromides without return of the disease, is a question I shall not enter into, as my own personal experience is not yet sufficiently extended to be able to form a practical opinion. A satisfactory solution of this problem could only be made after a life-long private practice, or by the accumulated experience of many observers. With hospital patients such is almost impossible, as they are lost sight of, especially if they recover.

Of the total 117 cases which compose the tables, we find that in no less than 97 were the attacks beneficially influenced by the bromides. In the different cases this improvement varies in degree, but in most of them it is very considerable – for example, Nos. 2, 5, 8, 11, 20, in Table I; Nos. 5, 6, 11, 15, in Table II; Nos. 3, 4, 5, 6, in Table III; and all the cases in Table IV. In these and others the attacks, if not actually arrested, were so enormously curtailed, both in number and severity, in comparison to what existed before treatment, as to constitute a most important change in the condition of the patient. In those cases in which improvement was not so well marked, in many it was most decided, and in frequent instances caused life, which had become a burden to the patient and his friends, to be bearable.

Of the total number of cases, in 3 the administration of the bromides had no effect whatever in diminishing the attacks, and in 3 others the number of seizures was greater after treatment than before. Whether in these last this circumstance was the result of the drug, or due to some co-incident augmentation of the disease itself, I cannot decide, but am inclined to believe in the latter as the explanation.

After a consideration of these facts it is difficult to understand why most physicians look upon epilepsy as an opprobrium medicinæ, and of all diseases as one of the least amenable to treatment, and the despair of the therapeutist. For example, Nothnagel, one of the most recent and representative authorities on the subject, in speaking of the treatment of epilepsy, says, "Many remedies and methods of treatment have isolated successes to show, but nothing is to be depended on; nothing can, on a careful discrimination of cases, afford a sure prospect of recovery, or even improvement." Such a statement indicates either an imperfect method of treatment, or that in Germany epilepsy is more intractable than in this country, as a "careful discrimination" of the above cases affords a "sure prospect of improvement" and a reasonable one of recovery. That a critical spirit and healthy scepticism should exist regarding the vague and imperfect accounts of the efficacy of various drugs in disease is, I believe, necessary to arrive at the truth; at the same time, we must not refuse to credit evidence sufficiently based on observation and experiment. The above collection of cases are facts, carefully and laboriously recorded, and not originally intended for the purpose which they at present fulfil. Having been brought up in the belief that epilepsy was one of the most intractable of diseases, no one is more surprised than myself at the readiness with which it responds to treatment. So far, then, from this affection being the despair of the profession, I believe that of all chronic nervous diseases it is the one most amenable to treatment by drugs, resulting, if not in complete cure, in great amelioration of the symptoms which practically constitute the disease.

An important consideration next arises. Assuming that practically the treatment in all cases is alike, are there any special circumstances which explain why some patients should have no attacks while under the influence of the drugs, while others are only relieved; why some – though the number is very small – should receive no benefit, and others have a larger number of attacks after treatment? On a careful examination of all the clinical facts of each case, no explanation can be found, the same form of attack, the same complications and circumstances, occupying each group. For example, one of those who had no attacks during treatment was a woman who had been afflicted with epilepsy for eighteen years, of a severe form, with general convulsions, biting tongue, etc. Another was a very delicate, nervous woman, who suffered, in addition to the seizures, from pulmonary and laryngeal phthisis, who came of a family impregnated with epilepsy, and whose intellect was greatly impaired. By far the largest class are those benefited by treatment, and these comprehend every species of case, chronic and recent, complicated, inherited, in the old and young, and so on; yet the most careful analysis fails to discover why some should be more amenable to treatment than others, or give any indication which might be useful in prognosis. Neither does a study of the few cases which the bromides did not affect, or those which increased in severity under their influence, throw any light upon the subject, as some of these latter gave no indications beforehand of their unfortunate termination, and in none of them was there any serious complication or special departure from good mental or bodily health.

Another point must be noted, although there is no statistical method of demonstrating the fact, namely, that in those cases in which the attacks were not completely arrested, but only diminished in number, those seizures which remained were frequently greatly modified in character while the patient was under the influence of the bromides. These were less severe, and characterized by the patients as "slight," while formerly they were "strong." This by itself often proves of great service, as, instead of a severe convulsive fit, in which the patient severely injures himself, bites his tongue, etc., he has what he calls a "sensation," in other words, an abortive attack.

Having considered the general effects of the bromides on a series of unselected cases, we now proceed to investigate whether any particular form of the disease, or any special circumstances connected with the patient or his surroundings, have any influence in modifying the results of treatment. The following table shows epilepsy divided into its two chief forms, namely, E. Gravior and E. Mitior. By the former is understood the ordinary severe attack, with loss of consciousness and convulsions; the latter is the slighter and very temporary seizure, of loss of consciousness, but without convulsions.

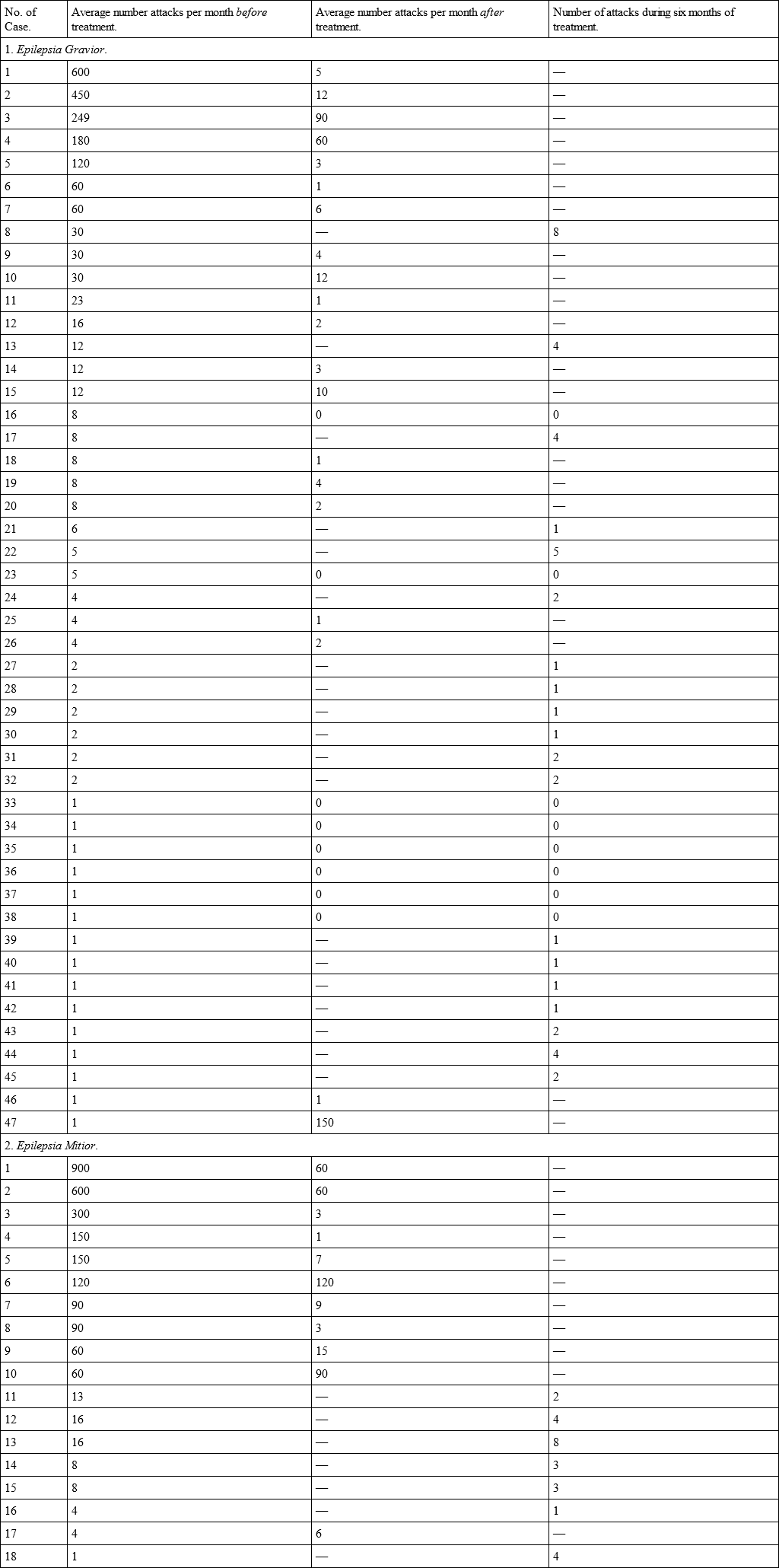

Table V. —Showing Results of Treatment by the Bromides in– 1. Epilepsia Gravior; and 2. Epilepsia Mitior.

Of 47 cases of E. Major, we find that in 8 there were no attacks during the whole period of treatment, in 1 there was no improvement, in 1 the attacks were augmented after treatment, and in 37 there was marked and varying diminution of the seizures. Of 18 cases of E. Mitior there was no case where the attacks were wholly suspended, in 1 there was no improvement, in 2 the attacks were increased, and in 15 they were diminished in number by treatment. This is scarcely a fair comparison between the two forms, as the numbers are so unequal; but cases of uncomplicated E. Mitior are not common, being generally associated with the graver form, which combined cases are not inserted in this table. It is generally asserted in books that the non-convulsive form is much more intractable than the other, but the above table proves the contrary, as, for example, in Nos. 3, 4, 11, 12. It is true that the results do not appear so complete or striking in E. Mitior as in E. Gravior, but then it must be remembered that the number of cases is more limited, and the number of attacks originally much greater. In short, the table shows that if treatment does not completely avert the attacks of E. Mitior, it greatly diminishes their frequency.

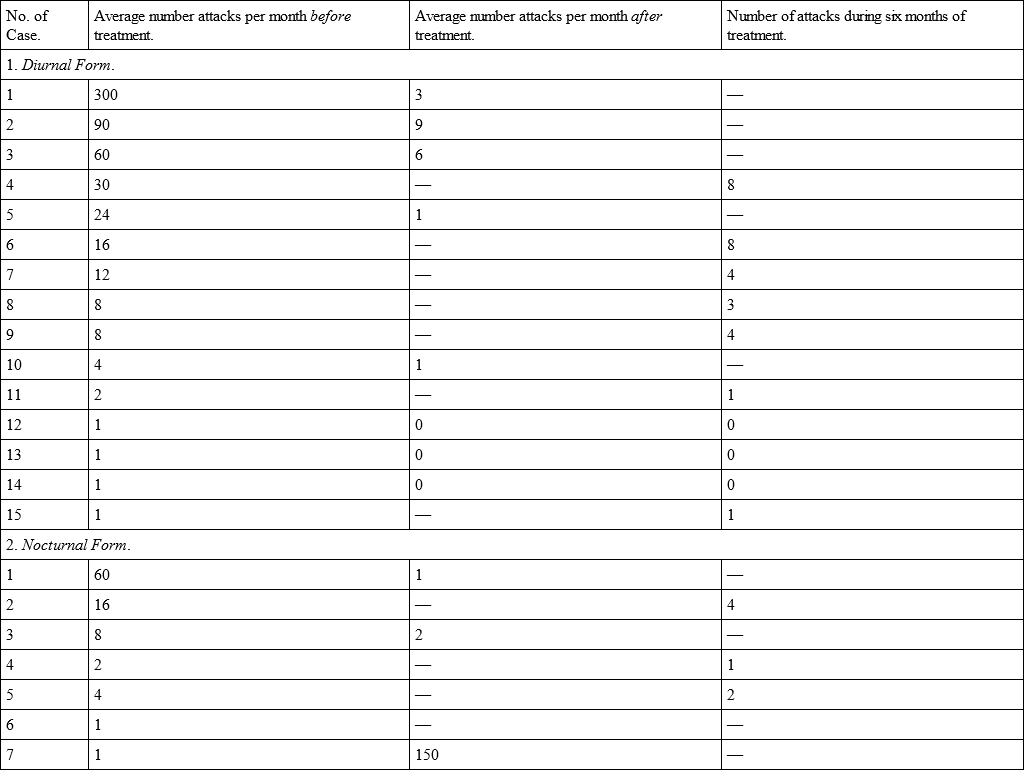

TABLE VI. —Showing Effects of Treatment by the Bromides in Epilepsy. 1. Diurnal Form; 2. Nocturnal Form.

Another variety of epilepsy is that which is characterized by the time at which the attacks occur. In the large majority of cases these take place both while the patient is awake and when he is asleep. I have, unfortunately, no observations to offer as to the effects of treatment on the diurnal or nocturnal attacks in patients suffering from both. The preceding table shows the result of treatment in 15 cases in which the attacks occurred only while the patient was awake, and in 7 cases where they took place only while he was asleep.

Of 15 cases of the purely diurnal form, we find that in 3 there was a total cessation of attacks during treatment, and in all the others there was diminution in their number. Of the 7 nocturnal cases, in none were the seizures entirely arrested, in 1 the attacks increased in number after treatment, and the remainder were relieved to a greater or less extent. Here, again, our numbers are small, and therefore difficult to found any definite principle upon; still there is enough to show that, contrary to the opinion expressed by most authorities, the nocturnal form of epilepsy appears to be as amenable to relief as the diurnal variety.

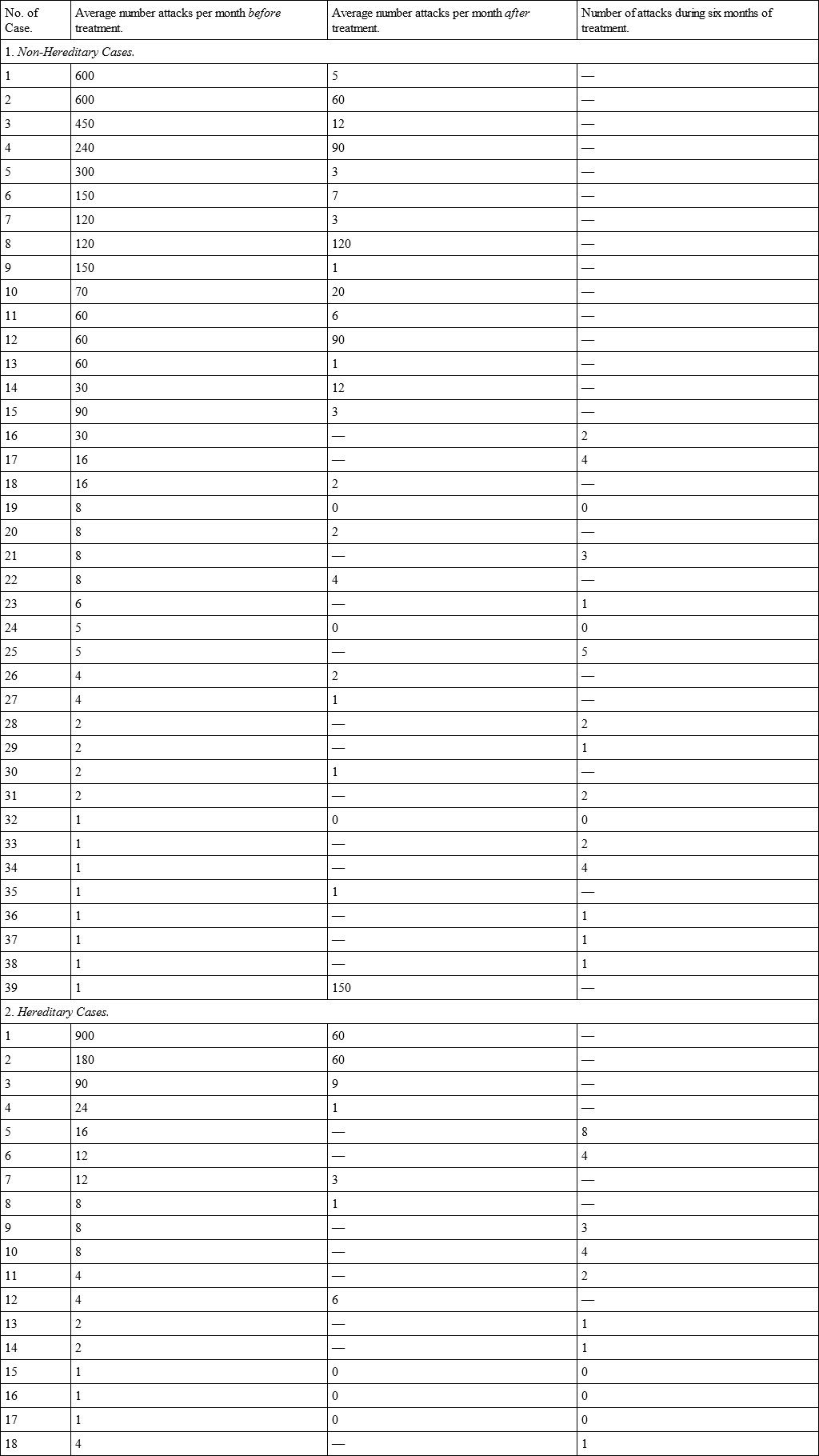

The next point for consideration is the question whether the fact of the epilepsy being hereditary or not makes any difference in the results of treatment by the bromides. In the following table all the cases with a perfectly sound family history are placed in the first part, and the second includes those in which either epilepsy or insanity could be proved to exist in any near relation.

Thus in 39 cases with a perfectly sound family history, in 3 the attacks were totally arrested during treatment, in 2 there was no improvement, in 2 there was increase of seizures after treatment, and in the remainder there was diminution of the fits. In 18 cases, where at least one near relation suffered from either epilepsy or insanity, in 3 the attacks were arrested, in 1 they were increased, and in the remainder diminished. In short, from a review of the details of the table, it does not appear that the fact of the disease being inherited, or of its existing in other members of the family, makes any difference to the benefit we may expect to derive from treatment.

Table VII. —Showing Effects of Treatment by the Bromides in Epilepsy. 1. Non-Hereditary Cases, 2. Hereditary Cases.

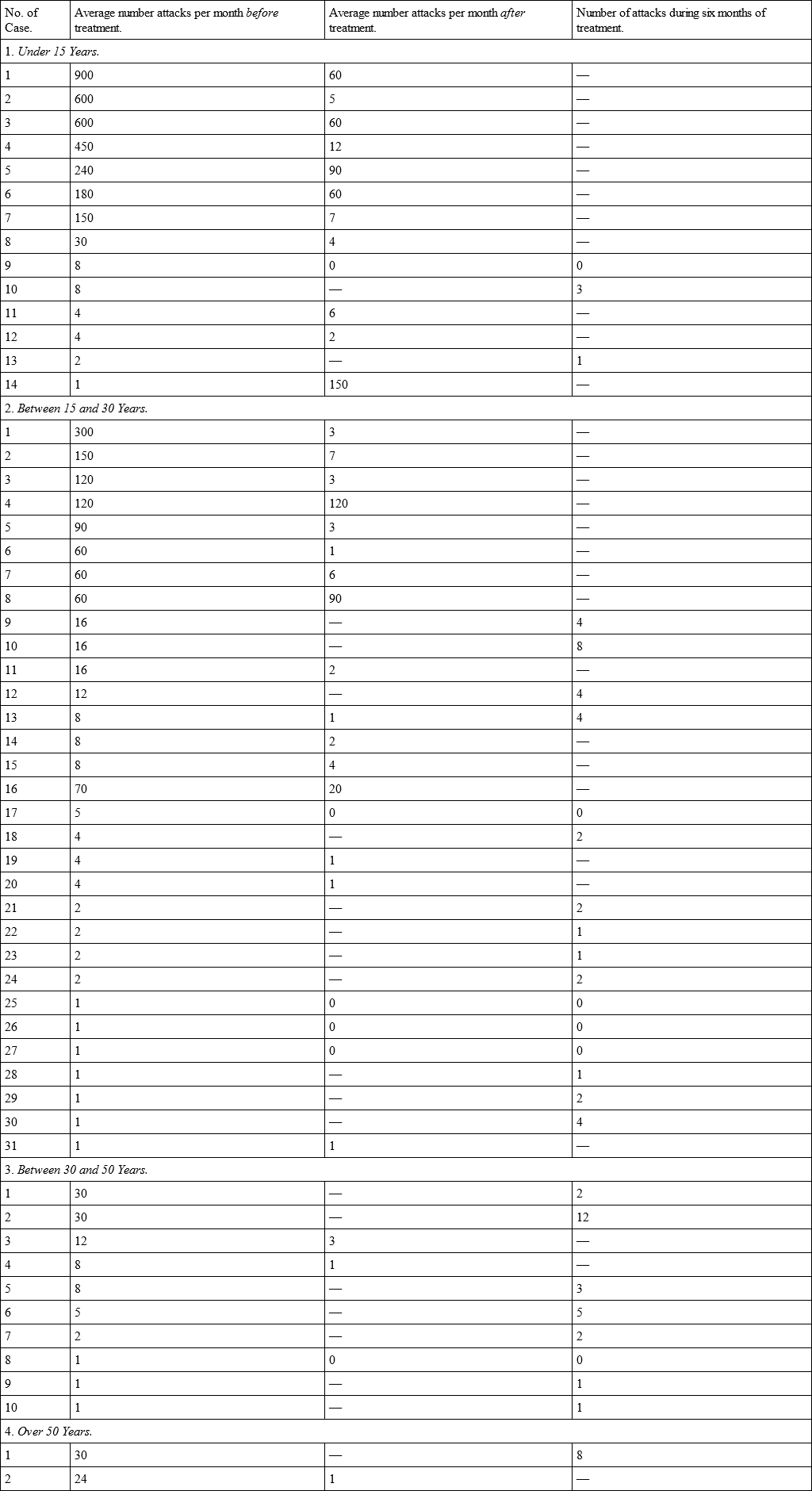

The next table attempts to show whether or not the age of the patient when he came under observation has any effect in modifying the action of the bromides, or whether it assists us prognosing the probable result.

A survey of this table shows in general terms that the age of the patient is neither an assistance nor impediment to the successful action of the bromides in the treatment of epilepsy. Whatever the age may be, whether in a young child or in an old person, the average of beneficial effects appears to be the same. At first sight it would seem as if treatment would be more successful in the young; but it is not so, as the two cases in the table over fifty years of age received as much average benefit as any of the others.

Table VIII. —Showing Effects of Treatment by the Bromides in Epilepsy at Different Ages. 1. Under 15 Years; 2. Between 15 and 30 Years; 3. Between 30 and 50 Years; 4. Over 50 Years.

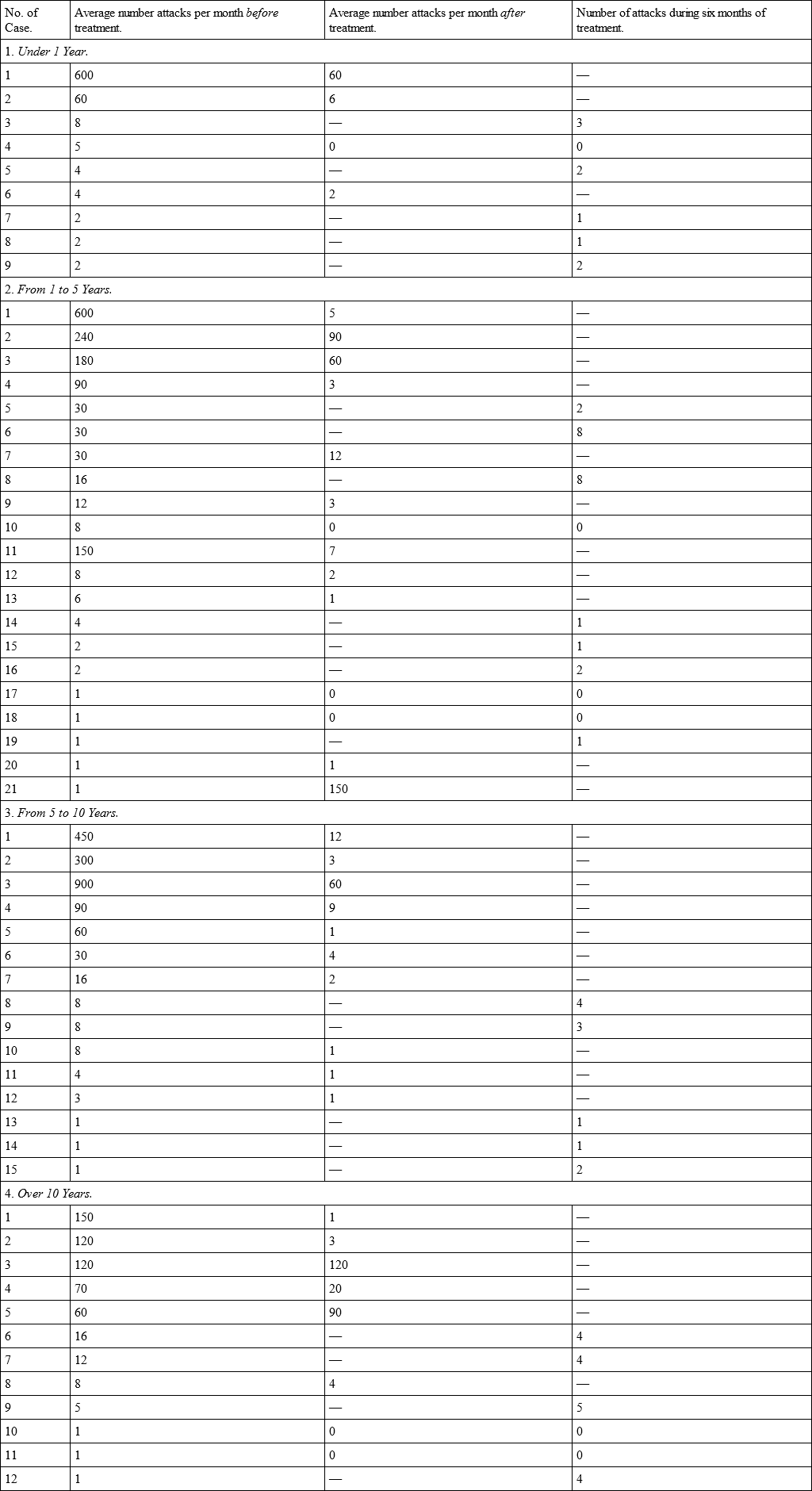

Does the fact of the disease being recent or chronic affect the prognosis of treatment? This will be seen by the following table, in which the length of time that the disease has existed is divided into four periods, namely – 1, those cases in which the attacks first began less than a year before treatment was commenced; 2, those in which they had begun from one to five years before; 3, those in which they began from five to ten years before; and, 4, those in which the disease had existed for over ten years.

Table IX. —Showing Effects of Treatment by the Bromides in Epilepsy in Recent and Chronic Cases. 1. Under 1 Year; 2. From 1 to 5 Years; 3. From 5 to 10 Years; 4. Over 10 Years.

In this table we observe very singular results in the treatment of this remarkable disease. In most ailments, the longer they have existed and the more chronic they are, the more difficult and imperfect is the prospect of recovery. This does not appear to hold good in the case of epilepsy. For when we analyze the above table we find that the results, on an average, are as satisfactory in those cases in which the disease has existed over ten years as in those which began less than one year before the patient came under observation. For example, we find in section 4 of Table IX. 12 cases in which epilepsy had existed for over ten years prior to treatment; of these, in 2 the attacks were completely arrested, in 1 there was no improvement, in 1 the attacks were increased, and in the remainder the seizures were as beneficially modified as in the other sections. Thus it would seem that we are not to be deterred from treating cases of epilepsy, however chronic they may be, as the results appear to be as good in modifying the attacks in old, as in recent cases.

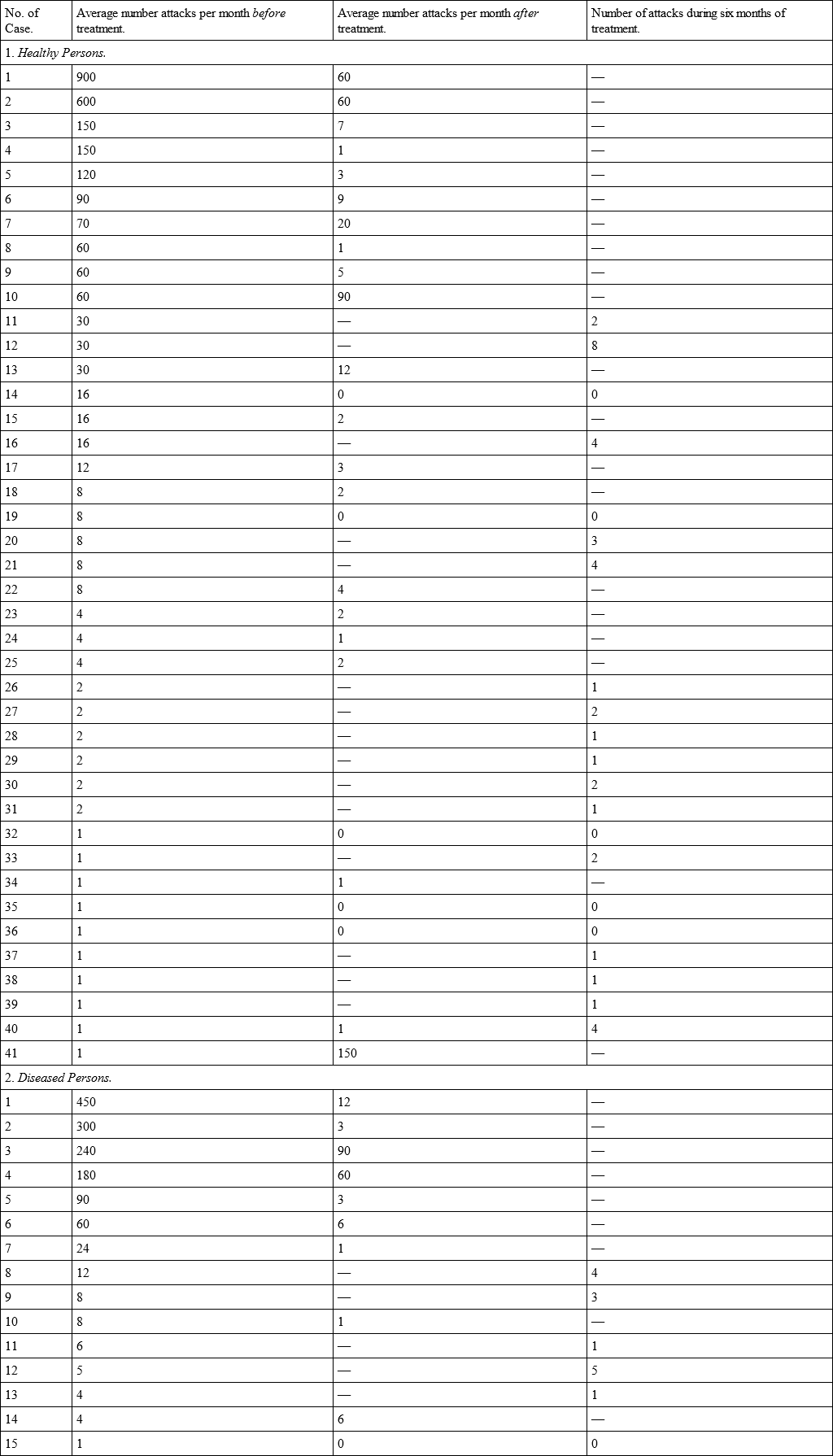

Table X. —Showing Effects of Treatment by the Bromides in Epilepsy – 1. In Healthy Persons; 2. In Diseased Persons.

Another important question arises: Does the general health of the patient in any way influence the effects of treatment? In the preceding table those cases are collected in section 1 whose general health was to all appearances robust and free from disease. In section 2. are those in which organic disease could be demonstrated, or in which the condition of the patient was evidently unfavourable.

Here, again, a consideration of the table demonstrates that the condition of the general health has no influence on the successful progress of treatment, as those cases under the head of diseased persons made apparently as satisfactory progress as those in a perfectly robust condition regarding their epileptic symptoms.

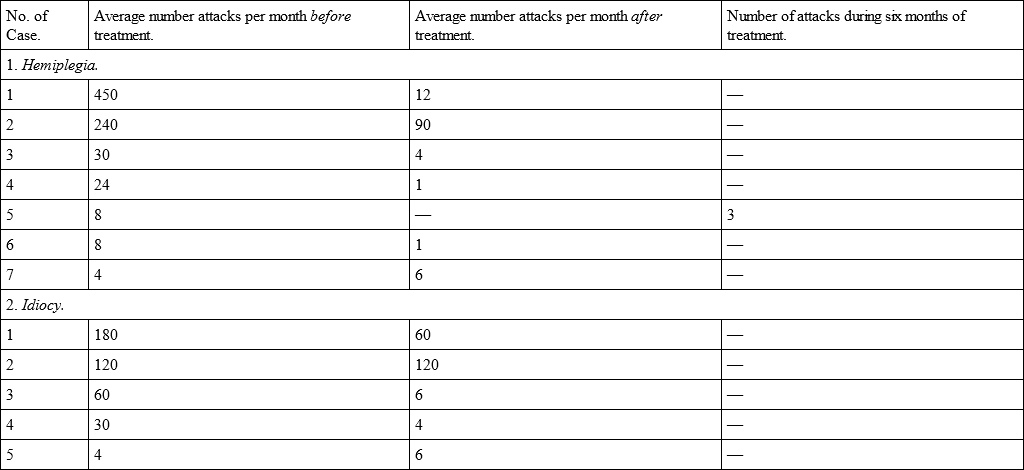

As a specimen, the following table shows the result in those cases complicated with a permanent lesion of a motor part of the brain, namely, hemiplegia, and of an intellectual portion, in the shape of idiocy: —

Table XI. —Showing effects of Treatment by the Bromides in Epilepsy complicated with – 1. Hemiplegia; 2. Idiocy.

Here it may be observed that of 7 cases complicated with hemiplegia, in 1 the attacks were increased after treatment, but all the others were relieved in average proportion. Of the 5 cases in idiots, in 1 there was no improvement, in 1 the attacks were subsequently augmented, and in the others there was improvement. The numbers are far too limited to found any reliable dictum upon; at the same time, it must be admitted that while epilepsy complicated with these grave lesions is perfectly amenable to treatment, this table serves to show that the proportion of non-success is comparatively large.

It has been stated before that no attempt would be made in this paper to prove that epilepsy was curable by therapeutic means. Its aim has been to show the effects of the bromides on the attacks or symptoms of that disease. It is common to hear it remarked, as if this were of no importance, "You only arrest the fits, but you do not know, and cannot cure, the original lesion. You do not go to the fountain-head of the disease, but simply relieve its results." In reply, I would ask, Of what disease do we know the ultimate nature any better than that of epilepsy? and if we did, how would that assist us in treating it? What drug in our pharmacopœia cures any single disease, or do other than, by attacking and relieving symptoms, leave nature to remove the morbid lesion? Even quinine, to which therapeutists triumphantly point, only arrests certain paroxysms until time removes the poison from the blood, as it does in most malarious affections. So far from being a small matter, I believe there are few, if any, drugs at our disposal which can be demonstrated to have a more beneficial action in the treatment of disease than that of the bromides, in epilepsy. Besides, I decline to admit the statement that complete recovery does not follow their administration. Various authors have reported cases, and that these are rare is due to reasons stated before, and chiefly on account of the long period of treatment necessary to ensure success.

This inquiry may be summed up in the following general conclusions: —

In 12.1 per cent. of epileptics the attacks were completely arrested during the whole period of treatment by the bromides.

In 83.3 per cent. the attacks were greatly diminished both in number and severity.

In 2.3 per cent. the treatment had no apparent effect.

In 2.3 per cent. the number of attacks was augmented during the period of treatment.

The form of the disease, whether it was inherited or not, whether complicated or not, recent or chronic, in the young or in the old, in healthy or diseased persons, appeared in no way to influence treatment, the success being nearly in the same ratio under all these conditions.

III.

AN INQUIRY INTO THE EFFECTS OF THE PROLONGED ADMINISTRATION OF THE BROMIDES IN EPILEPSY.4

The present inquiry is the result of an experience of 300 cases of epilepsy treated by myself with the bromides of potassium and ammonium. In all of these the clinical facts, as well as the progress of the malady, were carefully studied and recorded. The effects of the administration of these remedies on epileptic seizures I have already investigated and demonstrated in a somewhat elaborate series of observations.5 Further experience has confirmed the correctness of the general propositions then arrived at, so that they need not again be elaborated in detail.

At present it is proposed to direct attention to the effects of the prolonged administration of large doses of the bromides, and to attempt to ascertain if, while arresting or diminishing the frequency and severity of the paroxysmal symptoms, they beneficially influence the disease itself, or in any way injuriously modify the constitution of the patient. On this subject much difference of opinion and misconception prevail. It is well known that the injudicious use of the drugs leads to certain physiological phenomena which are comprised under the term "bromism." It is also generally believed that the physical and mental depression resulting from their prolonged toxic effects constitutes a condition worse than the malady for which they are exhibited. One of the objects of this article is to question the accuracy of this assertion, a true apprehension of which is the more important when we reflect how universal is this method of treatment, and the deterrent effect it exercises upon epileptic attacks. The task, like other therapeutic inquiries – especially those connected with chronic disease – is a difficult one, there being innumerable pitfalls of error between us and a sound scientific conclusion. These, however, may, I believe, in great measure be surmounted by the accumulation of facts laboriously and accurately recorded, by the intelligent study of their details, and the impartial and logical deductions which may be drawn from the data supplied. The value of a therapeutic inquiry depends, not upon the opinions and undigested experience of individuals, or by the narration of isolated cases, but upon the indisputable proofs resulting from the unbiassed analysis of a large series of accurately observed and unselected examples. The solution of the problem, if complex in all clinical affections, is especially so in epilepsy. Although the symptoms of this disease have been recognised from the earliest ages, our knowledge of its essential nature is as yet shrouded in mystery. The etiology and pathology are practically undetermined. The phenomena are not only due to a varied series of morbid conditions, but may assume a multitude of forms and degrees of severity, which may be, on the one hand, of the briefest duration, or, on the other, of a life-long permanence. The symptoms may comprise not only a diversity of physical ailments, but intellectual disturbances of the most terrible import. The malady may attack not only many whose systems are predisposed to disease, but those of the most robust constitution and with a healthy, family history. The consequences of the disorder may be comparatively innocuous, but in other circumstances may be attended with the most disastrous effects on mind and body and even on life itself. In a disease presenting such an intricate and uncertain course, it is obviously a task of the utmost difficulty to scientifically estimate the exact value of any therapeutic measures which may be adopted for its relief. The effects on one symptom, and that the most prominent, can, however, be accurately determined – namely, the paroxysmal seizures, which are definite and computable; and this has already been accomplished with tolerable precision.6 On the influence of the bromides on the disease itself, or on the epileptic state, we have less accurate information. In attempting to throw some light on this subject, two preliminary considerations must be recognised – 1st, the physiological actions of the drug on the healthy subject; and 2nd, the inter-paroxysmal symptoms of the epileptic constitution.