полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Albert Gallatin

Opposed to this view stood the letter of the Constitution. We now know, too, through Mr. Madison’s Notes, that when the question of eligibility to the House of Representatives came before the Convention on August 13, 1788, both Mr. Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris tried to obtain an express admission of the self-evident rights of actual citizens. For unknown reasons Mr. Morris’s motion was defeated by a vote of 6 States to 5. Failing here, he seems to have succeeded in regard to the Presidency by inserting his proviso in committee, and no one in the Convention subsequently raised even a question against its propriety. Of course the Senate was at liberty now to put its own interpretation on this obvious inconsistency, and the Senate was so divided that one member might have given Mr. Gallatin his seat. The vote was 14 to 12, with Vice-President John Adams in his favor had there been a tie. There was no tie, and Mr. Gallatin was thrown out. He always believed that his opponents made a political blunder, and that the result was beneficial to himself and injurious to them.

GALLATIN TO THOMAS CLAREPhiladelphia, 5th March, 1794.… I have nothing else to say in addition to what I wrote you by my last but what Mr. Badollet can tell you. He will inform you of what passed on the subject of my seat in the Senate, and that I have lost it by a majority of 14 to 12. One vote more would have secured it, as the Vice-President would have voted in my favor; but heaven and earth were moved in order to gain that point by the party who were determined to preserve their influence and majority in the Senate. The whole will soon be published, and I will send it to you. As far as relates to myself I have rather gained credit than otherwise, and I have likewise secured many staunch friends throughout the Union. All my friends wish me to come to the Assembly next year…

After this rebuff, Mr. Gallatin, being thrown entirely out of politics for the time, began to pay a little more attention to his private affairs. He could not at this season of the year set out for Fayette, and accordingly returned to New York, where he left his wife with her family, while he himself went back to Philadelphia to make the necessary preparations for their western journey and future residence. Here he sold a portion of his western lands to Robert Morris, who was then, like the rest of the world, speculating in every species of dangerous venture. Like everything else connected with land, the transaction was an unlucky one for Mr. Gallatin.

GALLATIN TO HIS WIFEPhiladelphia, 7th April, 1794.We arrived here, my dearest friend, on Saturday last… No news here. You will see by the newspapers the motion of Mr. Clark to stop all intercourse with Great Britain. I believe it is likely to be supported by our friends. Dayton is quite warm. The other day, when it was observed in Congress by Tracy that every person who would vote for this motion of sequestering the British debts must be an enemy to morality and common honesty, ‘I might,’ replied Dayton, – ‘I might with equal propriety call every person who will refuse to vote for that motion a slave of Great Britain and an enemy to his country; but if it is the intention of those gentlemen to submit to every insult and patiently to bear every indignity, I wish (pointing to the eastern members, with whom he used to vote), —I wish to separate myself from the herd.’

The majority of the Assembly of Pennsylvania had several votes, previous to the election of a Senator in my place, to agree upon the man. Sitgreaves, a certain Coleman, of Lancaster County, a fool and a tool, and James Ross, were proposed and balloted for. Ross had but seven votes, on account of his being a western man and a man of talents, who upon great many questions would judge for himself. They divided almost equally between Sitgreaves and Coleman, and at last agreed to take up Coleman, in order to please the counties of Lancaster and York. Our friends, who were the minority, had no meeting, and waited to see what would be the decision of the other party, in hopes that they might divide amongst themselves. As soon as they saw Coleman taken up they united in favor of Ross as the best man they had any chance of carrying, and they were joined by a sufficient number of the disappointed ones of the other party to be able to carry him at the first vote. As he comes chiefly upon our interest, I hope he will behave tolerably well, and, upon the whole, although it puts any chance of my being again elected a member of that body beyond possibility itself, I am better pleased with the fate of the election than most of our adversaries…

Philadelphia, 19th April, 1794.… I have concluded this day with Mr. Robert Morris, who, in fact, is the only man who buys. I give him the whole of my claims, but without warranting any title, for £4000, Pennsylvania currency, one-third payable this summer, one-third in one year, and one-third in two years. That sum therefore, my dearest, together with our farm and five or six hundred pounds cash, makes the whole of our little fortune. Laid out in cultivated lands in our neighborhood it will provide us amply with all the necessaries of life, to which you may add that, as property is gradually increasing in value there, should in future any circumstances induce us to change our place of abode, we may always sell to advantage…

Early in May Mr. and Mrs. Gallatin set out for Fayette. His mind was at this time much occupied with his private affairs and private anxieties. His sale of lands to Robert Morris had, as he hoped, relieved him of a serious burden; but he was again trying the experiment of taking an Eastern wife to a frontier home, and he was again driven by the necessities and responsibilities of a family to devise some occupation that would secure him an income. The farm on George’s Creek was no doubt security against positive want, but in itself or in its surroundings offered little prospect of a fortune for him, and still less for his children.

He had barely reached home, and his wife had not yet time to set her house in order and to get the first idea of her future duties in this wholly strange condition of life, when a new complication threatened them with dangers greater than any which their imaginations could have reasonably painted. They suddenly found themselves in the midst of violent political disturbance, organized insurrection and war, an army on either side.

For eighteen months Mr. Gallatin had almost lost sight of the excise agitation, and possibly had not been sorry to do so. Throughout his political life he followed the sound rule of identifying himself with his friends and of accepting the full responsibility, except in one or two extreme cases, even for measures which were not of his own choice. But under the moderation of his expressions in regard to the Pittsburg resolutions of 1792 it seems possible to detect a certain amount of personal annoyance at the load he was thus forced to carry, and a determination to keep himself clear from such complications in future. The year had been rather favorable than otherwise to the operation of the excise law. To use his own language in his speech of January, 1795: “It is even acknowledged that the law gained ground during the year 1793. With the events subsequent to that meeting [at Pittsburg] I am but imperfectly acquainted. I came to Philadelphia a short time after it, and continued absent from the western country upon public business for eighteen months. Neither during that period of absence, nor after my return to the western country in June last, until the riots had begun, had I the slightest conversation that I can recollect, much less any deliberate conference or correspondence, either directly or indirectly, with any of its inhabitants on the subject of the excise law. I became first acquainted with almost every act of violence committed either before or since the meeting at Pittsburg upon reading the report of the Secretary of the Treasury.”

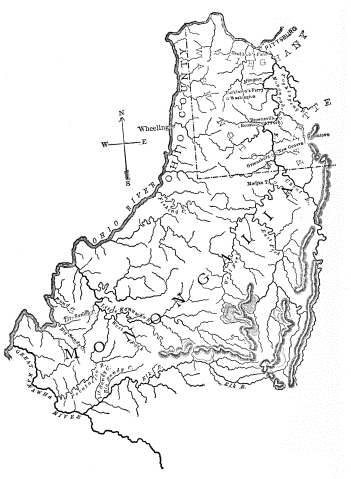

Occasional acts of violence were committed from time to time by unknown or irresponsible persons with intent to obstruct the collection of the tax, but no opposition of any consequence had as yet been offered to the ordinary processes of the courts; not only the rioters, wherever known, but also the delinquent distillers, were prosecuted in all the regular forms of law, both in the State and the Federal courts. The great popular grievance had been that the distillers were obliged to enter appearance at Philadelphia, which was in itself equivalent to a serious pecuniary fine, owing to the distance and difficulty of communication. In modern times it would probably be a much smaller hardship to require that similar offenders in California and Texas should stand their trial at Washington. This grievance had, however, been remedied by an Act of Congress approved June 5, 1794, by which concurrent jurisdiction in excise cases was given to the State courts. Unluckily, this law was held not to apply to distillers who had previously to its enactment incurred a penalty, and early in July the marshal set out to the western country to serve a quantity of writs issued on May 31 and returnable before the Federal court in Philadelphia. All those in Fayette County were served without trouble, and the distillers subsequently held a meeting at Uniontown about the 20th July, after the riots had begun elsewhere and the news had spread to Fayette; a meeting which Mr. Gallatin attended, and at which it was unanimously agreed to obey the law, and either abandon their stills or enter them. In fact, there never was any resistance or trouble in Fayette County except in a part the most remote from Mr. Gallatin’s residence.

But the marshal was not so fortunate elsewhere. He went on to serve his writs in Alleghany County, and after serving the last he was followed by some men and a gun was fired. General Neville, the inspector, was with him, and the next day, July 16, General Neville’s house was approached by a body of men, who demanded that he should surrender his commission. They were fired upon and driven away, with six of their number wounded and one killed. Then the smouldering flame burst out. The whole discontented portion of the country rose in armed rebellion, and the well-disposed, although probably a majority, were taken completely by surprise and were for the moment helpless. The next day Neville’s house was again attacked and burned, though held by Major Kirkpatrick and a few soldiers from the Pittsburg garrison. The leader of the attacking party was killed.

The whole duration of the famous whiskey rebellion was precisely six weeks, from the outbreak on the 15th July to the substantial submission at Redstone Old Fort on the 29th August. This is in itself evidence enough of the rapidity with which the various actors moved. From the first, two parties were apparent, those in favor of violence and those against it. The violent party had the advantage in the very suddenness of their movement. The moderates were obliged to organize their force at first in the districts where their strength lay, before it became possible to act in combination against the disturbers of the peace. Of course an armed collision was of all things to be avoided by the moderates, at least until the national government could have time to act; in such a collision the more peaceable part of the community was certain to be worsted.

Mr. Gallatin, far away from the scene of disturbance, did not at first understand the full meaning of what had happened. He and his friend Smilie attended the meeting of distillers at Uniontown, and, although news of the riots had been received there, they found no difficulty in persuading the distillers to submit. He therefore felt no occasion for further personal interference until subsequent events showed him that there was a general combination to expel the government officers.14 But events moved fast. On the 21st July, the leaders in the attack on Neville’s house called a meeting at Mingo Creek meeting-house for the 23d, which was attended by a number of leading men, among whom were Judge Brackenridge and David Bradford.

Judge Brackenridge, then a prominent lawyer of Pittsburg, was a humorist and a scholar, constitutionally nervous and timid, as he himself explains,15 the last man to meet an emergency such as was now before him, and furthermore greatly inclined to run away, if he could, and leave the rebels to their own devices; he did nevertheless make a fairly courageous stand at the Mingo Creek meeting, and disconcerted the movements of the insurgents for the time. Had others done their duty as well as he, the organization of the insurgents would have ended then and there, but Brackenridge was deserted by the two men who should have supported him. James Marshall and David Bradford had gone over to the insurgents, and by their accession the violent party was enabled to carry on its operations. The Mingo Creek meeting ended in a formal though unsigned invitation to the townships of the four western counties of Pennsylvania and the adjoining counties of Virginia to send representatives on the 14th August to a meeting at Parkinson’s Ferry on the Monongahela.

Had this measure been left to itself it is probable that it would have answered sufficiently well the purposes of the peace party, since it allowed them time for consultation and organization, which was all they really required. Bradford and his friends knew this, and were bent on forcing the country into their own support; Bradford therefore conceived the ingenious idea of stopping the mail and seizing the letters which might have been written from Pittsburg and Washington to Philadelphia. This was done on the 26th by a cousin of Bradford, who stopped the post near Greensburg, about thirty miles east of Pittsburg, and took out the two packages. In the Pittsburg package were found several letters from Pittsburg people, the publication of which roused great offence against them, and, what was of more consequence, carried consternation among the timid. It was the beginning of a system of terror.

Certainly Bradford showed energy and ability in conducting his campaign, at least as considered from Brackenridge’s point of view. His stroke at the peace party through the mail-robbery was instantly followed up by another, much more serious and thoroughly effective. On the 28th July he with six others, among whom was James Marshall, issued a circular letter, in which, after announcing that the intercepted letters contained secrets hostile to their interest, they declared that things had now “come to that crisis that every citizen must express his sentiments, not by his words but by his actions.” This letter, directed to the officers of the militia, was in the form of an order to march on the 1st August, with as many of their command as possible, fully armed and equipped, with four days’ provision, to the usual rendezvous of the militia at Braddock’s Field.

This was levying war on a complete scale, but it was well understood that the chief object was to overawe opposition, more especially in Pittsburg, although the Federal garrison and stores in that city were also aimed at. The order met with strong resistance, and under the earnest remonstrances of James Ross and other prominent men, in a meeting at Washington, even Marshall was compelled to retract and assent to a countermand. But, notwithstanding their opposition, the popular vehemence in Washington County was such that it was decided to go forward, and, after a moment’s wavering, Bradford became again the loudest of the insurgent leaders.

On the 1st August, accordingly, several thousand people assembled at Braddock’s Field, about eight miles from Pittsburg. Of these some fifteen hundred or two thousand were armed militia, all from the counties of Washington, Alleghany, and Westmoreland; there were not more than a dozen men present from Fayette. Brackenridge has given a lively description of this meeting, which he attended as a delegate from Pittsburg, in the hope of saving the town, if possible, from the expected sack. Undoubtedly a portion of the armed militia might easily have been induced to attack the garrison, which would have led to the plundering of the town, but either Bradford wanted the courage to fight or he found opposition among his own followers. He abandoned the idea of assailing the garrison, and this formidable assemblage of armed men, after much vague discussion, ended by insisting only upon marching through the town, which was done on the 2d of August, without other violence than the burning of Major Kirkpatrick’s barn. A lively sense of the meaning of excise to the western people is conveyed by the casual statement that this march cost Judge Brackenridge alone four barrels of his old whiskey, gratuitously distributed to appease the thirst of the crowd; how much whiskey the western gentleman usually kept in his house nowhere appears, but it is not surprising under such circumstances that the march should have thoroughly terrified the citizens of Pittsburg and quenched all thirst for opposition in that quarter.

Mr. Gallatin did not attend the meeting at Braddock’s Field; it was not till after that meeting that the serious nature of the disturbances first became evident to him. What had been riot was now become rebellion. He rapidly woke to the gravity of the occasion when disorder spread on every side and even Fayette was invaded by riotous parties of armed men. A liberty-pole was raised, and when he asked its meaning he was told it was to show they were for liberty; he replied by expressing the wish that they would not behave like a mob, and was met by the pointed inquiry whether he had heard of the resolves in Westmoreland that if any one called the people a mob he should be tarred and feathered.16 Unlike many of the friends of order, he felt no doubts in regard to the propriety of sending delegates to the coming assembly at Parkinson’s Ferry, and, feeling that Fayette would inevitably be drawn into the general flame unless measures were promptly taken to prevent it, he offered to serve as a delegate himself, and was elected. All the friends of order did not act with the same decision. The meeting at Braddock’s Field was intended to control the elections to the meeting at Parkinson’s Ferry, and to a considerable extent it really had this effect. The peace party was overawed by it. The rioters extended their operations; chose delegates from all townships where they were a majority, and from a number where they were not, and made an appearance of election in some places where no election was held. The peace party hesitated to the last whether to send delegates at all.

When the 14th of August came, all the principal actors were on the spot, – Bradford, Marshall, Brackenridge, Findley, and Gallatin, – 226 delegates in all, of whom 93 from Washington, 43 from Alleghany, 49 from Westmoreland, and 33 from Fayette, 2 from Bedford, 5 from Ohio County in Virginia, and about the same number of spectators. They were assembled in a grove overlooking the Monongahela. Marshall came to Gallatin before the meeting was organized, and showed him the resolutions which he intended to move, intimating at the same time that he wished Mr. Gallatin to act as secretary. Mr. Gallatin told him that he highly disapproved the resolutions, and had come to oppose both him and Bradford, therefore did not wish to serve. Marshall seemed to waver; but soon the people met, and Edward Cook, who had presided at Braddock’s Field, was chosen chairman, with Gallatin for secretary.

Bradford opened the debate by a speech in which, beginning with a history of the movement, he read the original intercepted letters, and stated the object of the present meeting as being to deliberate on the mode in which the common cause was to be effectuated; he closed by pronouncing the terms of his own policy, which were to purchase or procure arms and ammunition, to subscribe money, to raise volunteers or draft militia, and to appoint committees to have the superintendence of those departments. Marshall supported Bradford, and moved his resolutions, which were at once taken into consideration. The first denounced the practice of taking citizens to great distances for trial, and this resolution was put to vote and carried without opposition. The second appointed a committee of public safety “to call forth the resources of the western country to repel any hostile attempt that may be made against the rights of the citizens or of the body of the people.” It was dexterously drawn. It did not call for a direct approval of the previous acts of rebellion, but, by assuming their legality and organizing resistance to the government on that assumption, it committed the meeting to an act of treason.17

Mr. Gallatin immediately rose, and, throwing aside all tactical manœuvres, met the issue flatly in face. “What reason,” said he, “have we to suppose that hostile attempts will be made against our rights? and why, therefore, prepare to resist them? Riots have taken place which may be the subject of judicial cognizance, but we are not to suppose hostility on the part of the general government; the exertions of government on the citizens in support of the laws are coercion and not hostility; it is not understood that a regular army is coming, and militia of the United States cannot be supposed hostile to the western country.”18 He closed by moving that the resolutions should be referred to a committee, and that nothing should be done before it was known what the government would do.

Mr. Gallatin’s speech met the assumption that resistance to the excise was legal by a contrary assumption, without argument, that it was illegal, and thus threatened to force a discussion of the point of which both sides were afraid. Mr. Gallatin himself believed that the resolutions would then have been adopted if put to a vote; the majority, even if disposed to peace, had not the courage to act. Now was the time for Brackenridge to have thrown off his elaborate web of double-dealing and with his utmost strength to have supported Gallatin’s lead; but Brackenridge’s nerves failed him. “I respected the courage of the secretary in meeting the resolution,” he says,19 “but I was alarmed at the idea of any discussion of the principle.” “I affected to oppose the secretary, and thought it might not be amiss to have the resolution, though softened in terms.” Nevertheless, the essential point was carried; Marshall withdrew the resolution, and a compromise was made by referring everything to a committee of sixty, with power to call a new meeting of the people.

The third and fourth resolutions required no special opposition. The fifth pledged the people to the support of the laws, except the excise law and the taking citizens out of their counties for trial. Gallatin attacked this exception, and succeeded in having it expunged. A debate then followed on the adoption of the amended resolution, which was supported by both Brackenridge and Gallatin, and an incident said to have occurred in the course of the latter’s speech is thus related by Mr. Brackenridge:20

“Mr. Gallatin supported the necessity of the resolution, with a view to the establishment of the laws and the conservation of the peace. Though he did not venture to touch on the resistance to the marshal or the expulsion of the proscribed, yet he strongly arraigned the destruction of property; the burning of the barn of Kirkpatrick, for instance. ‘What!’ said a fiery fellow in the committee, ‘do you blame that?’ The secretary found himself embarrassed; he paused for a moment. ‘If you had burned him in it,’ said he, ‘it might have been something; but the barn had done no harm.’ ‘Ay, ay,’ said the man, ‘that is right enough.’ I admired the presence of mind of Gallatin, and give the incident as a proof of the delicacy necessary to manage the people on that occasion.”

Opposite this passage on the margin of the page, in Mr. Gallatin’s copy of this book, is written in pencil the following note, in his hand:

“Totally false. It is what B. would have said in my place. The fellow said, ‘It was well done.’ I replied instantly, ‘No; it was not well done,’ and I continued to deprecate in the most forcible terms every act of violence. For I had quoted the burning of this house as one of the worst.”

The result of the first day’s deliberation was therefore a substantial success for the peace party, not so much from what they succeeded in effecting as from the fact that they had obtained energetic leadership and the efficiency which comes from confidence in themselves. The resolutions were finally referred to a committee of four, – Gallatin, Bradford, Herman Husbands, and Brackenridge; a curious party in which Brackenridge must have had a chance to lay up much material for future humor, Bradford being an utterly hollow demagogue, Husbands a religious lunatic, and Brackenridge himself a professional jester.21