полная версия

полная версияThe Church of Grasmere: A History

In 1879, when the volume of accounts closes, the year's expenditure stands at £155 14s. 1d.

NON-RATEPAYERS

The religious factions – whether Baptist, Anabaptist, Independent or Presbyterian – that had sprung up during the Commonwealth left behind them no vital seeds of dissent in the wide parish of Grasmere, although the two last had in turn held the rectorate and the pulpit. As soon, indeed, as the Episcopal Church was restored, along with the Monarchy, the people returned with apparently a willing mind, and almost unanimously, to the old order of worship.

There was an exception, however, to be found in the Quakers, who were firm in refusing to re-enter the Church. George Fox, wandering on foot like an old Celtic missionary, had made his appearance in these parts in 1653, and at once his preaching (which mirrored his mystic and simple mind), united with a magnetic personality, had secured him a following. His teaching discountenanced all creeds, forms, and ritual. His meetings were, therefore, held in private houses; and so much abhorred by his followers was the "steeple-house" with its consecrated ground, as well as any fixed form of service (even the Office for the Burial of the Dead), that they often laid their dead in silence in their own garden-ground, rather than carry them to the church.

As the little band grew larger, a plot of ground was, however, secured as early as 1658 at Colthouse, near Hawkshead, in Lancashire, as a graveyard187; and in that neighbourhood, where they built a meeting-house in 1688,188 they became numerous and active; and on the Westmorland side of the Brathay – in Langdale and in Loughrigg more especially – George Fox also found adherents. In particular, Francis Benson, freeholder of the Fold, of a wealthy family of clothiers, and an influential man who served as Presbyterian elder in 1646, became his follower; and remained so through the persecutions. He received Fox into his house, even when the preacher had become a marked man. Fox's Journal, after recording his Keswick preachings in 1663, runs on: —

We went that night to one Francis Benson's in Westmorland; near Justice Fleming's House. This Justice Fleming was at that time in a great Rage against Friends, and me in particular; insomuch that in the open Sessions at Kendal just before, he had bid Five Pounds to any Man, that should take me; that Francis Benson told me. And it seems as I went to this Friend's House, I met one Man coming from the Sessions, that had this Five Pounds offered him to take me, and he knew me; for as I passed by him, he said to his Companion, That is George Fox: Yet he had not power to touch me: for the Lord's power preserved me over all.

The fanatical spirit of Fox is shown perhaps in this passage, where he ascribes the inaction of these two parishioners of Grasmere, not to a generous tolerance of mind (certainly God-given), but to a direct interposition of Providence in his own favour. He likewise attributes the death of the Squire's good and gentle wife later on to God's wrath and judgment upon the husband for his persecution of the Friends.

In truth, Squire Daniel was not the man to view leniently the opposition offered by the new sect to the restoration of the old form of worship. It must be allowed that the method of their preachers was not only irritating but provocative; for it was their wont, when the congregation was assembled in the "steeple-house" to rise and denounce both worship and officiating clergy as instruments of Belial; with an occasional result of rough handling and ejection by the people. We have seen that William Wilson, a Langdale man and one of their speakers, resorted to this method of interruption when the Church of England service was restored in the chapel. The parson of Windermere later on wrote to Squire Daniel begging his magisterial help, as a woman was in the habit of rising during worship and denouncing him. Wilson's misdemeanour was immediately dealt with at the Quarter Sessions, and on his refusing to swear the oath – a matter of principle with the Quakers, which was not rightly understood, and which made their offence a political one – was thrown into gaol, where, if his fine of a hundred marks was not paid in six weeks, he was to remain for six months, and to be brought again before the magistrates.189

This was certainly a severe judgment. How the case ended is not apparent, nor how long Wilson remained in prison. A letter exists at Rydal Hall, addressed to "Justice fleeming" and signed L.M., reproaching him for his treatment of the Quakers, especially of the four now in prison. One of these is "Wm. Willson, thy poore neighbour," of whose wife and children the Squire is admonished to have a care, since the prisoner had little but what he got by his hands – a statement which implies that Wilson was a craftsman.

The Rydal Squire had at first believed that he could force the Friends back to the common worship in the old parish church by means of fines, for he had the frugal man's belief that the pocket can be made to act upon the conscience. With the passing of the Act of Uniformity (1662) and the later Conventicle and Five Mile Acts, however, he and his fellow magistrates had a powerful legal hold over them. It is clear that he caused the known Quakers of the parish to be watched. One, James Russell, brought him word that there had been a meeting on November 1st, 1663, at the house of John Benson, of Stang End. This was on the Lancashire side of Little Langdale beck, but the Westmorland folk who attended were Francis Benson, his son Bernard, "Regnhold" Holme, Michael Wilson, and Barbara Benson. Of Lancashire folk there were only Giles Walker, wright, who had walked from Hawkshead, and William Wilson and his wife. Wilson was the speaker, so his imprisonment had not damped his ardour. Again, next year, the constable of Grasmere, Thomas Braithwaite, and a churchwarden, Robert Grigge, gave evidence that certain Quakers had been seen returning from Giles Walker's house near Hawkshead; and among them were William Harrison, of Langdale, and Edward Hird, of Grasmere.

These doings were not passed over by the Squire. He even tried conclusions with the most powerful of the sect, Francis Benson, of the Fold, and accordingly the latter was summoned, in 1663, along with his wife Dorothy, to appear at the Quarter Sessions to answer the charge of having been present at a meeting. The penalty of non-appearance was a fine of thirty shillings, while the fines of John Dixon and William Harrison, both of Langdale, charged with the same offence, were respectively twenty shillings and ten shillings. Francis Benson probably cleared his legal mis-demeanours by money payments, for no evidence has been found of his imprisonment. He and his family, however, remained staunch Friends. The place of his sepulchre is not known, though his death is recorded for February, 1673, of "Fould in Loughrig," in the Quaker Registers. There is a tradition of a burying-ground at the Fold, somewhere about his now vanished homestead, and it is quite possible that some members of the family might be buried there, as the early Friends not infrequently made a grave-plot on their own ground. The Fold was so much a centre of the sect that a marriage took place there between William Satterthwaite, of Colthouse, and the daughter of Giles Walker, of Walker Ground, Hawkshead, on December 11th, 1661.190 According to another tradition, a Baptist Meeting-house stood at the Fold, and an old man, named Atkinson, whose forbears had owned the adjacent farmhold of the Crag – where he was then living – pointed out the exact spot on a little triangle by the road where the building had stood, and the "Dipping" took place. But this story is against all record, for we can trace the Bensons' adherence to the Friends to a late period.

A large number of Quakers travelled to Rydal in 1681 to make their Test or Declaration before Squire Daniel and his son, but the only folk of the parish among them were Bernard Benson, of Loughrigg, and Jane his wife, and "Regnald" Holme, of Clappersgate, and his wife Jane.

In 1684 a Rydal man "presented" before the justices quite a concourse of people who had been present at a "Conventicle" in Langdale. Some seventeen Loughrigg and Langdale names were cited: Edward Benson of High Close (his only appearance as a Dissenter), John Dixon of Rosset in Langdale, William and James Harryson of Harry Place, "Regnald" and Jane Holme of Loughrigg, James Holme, the Willsons of Langdale, etc.

Reginald Holme's name frequently appears in the Indictment Book of the Quarter Sessions, and generally in connection with secular disputes. He was, in fact, a turbulent character, little fitted to belong to the peace-loving sect, which he joined possibly from sheer love of dissent. Some items of his history have been given elsewhere. He owned the mill at Skelwith Bridge – probably then, as later, a corn-mill, though it is extremely likely that a walk-mill would be set up additionally on this fine flow of water. About this water and other matters he was in constant dispute with his neighbours. One altercation, with a certain Thomas Rawlingson, the Friends tried to settle for him but as he refused to accept their verdict, a resolution was passed at a Monthly Meeting, held at Swathmoor (1676), that the law might now take its course. On another occasion Reginald was brought up before the Magistrates for assault; but the recurring bone of contention was a dam or weir which he had built across the river for the good of his mill – and to the damage, it was declared, of the pathway above, and of his neighbours' grounds. The Rydal Squire twice headed a party for the forcible destruction of this dam, as has been told191; but long afterwards Holme was in fierce conflict with Michael Satterthwaite, of Langdale, yeoman, about this or another dam.192 Finally, in 1684, a crisis occurred, and Reginald's goods were seized by the strong arm of the law – a most unwonted proceeding; on which occasion his sons and his daughter fell upon the unfortunate officers, and beat them and put them forth with violence – which made another indictable offence.

After the law-suit concerning the tithes, which followed upon the Restoration (see ante), in which law-suit Francis Benson was concerned, and possibly other Quakers, we have no evidence as to whether the sect continued to oppose the payment of church scot. But there is abundant evidence to show that they were resolute in non-attendance at church, and in refusal to pay the church rate or "sess" levied on the townships for the upkeep of the fabric and its walls by the representative men of the parish. The Subsidy Rolls of 1675 show that Francis Benson paid for himself and his wife Dorothy the tax of 1s. 4d., which the Government demanded from all non-communicants, as did "Reynald" Holme for self and wife, and John Benson of Langdale.

From wardens' accounts and presentments we gain many particulars of the dissenters of the parish, who appear to diminish in number as time goes on. It had become necessary by 1694 to account, in the books, for the deficit caused by the Friends' non-payment; and though in the following year two of them yielded, Bernard Benson paying up the large arrears of 15s. 11d. for "Church: Sess," and Jacob Holme 7s. 6d., the "Allowance for Dissenters" appears each year on the debit side.

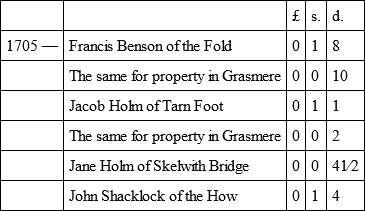

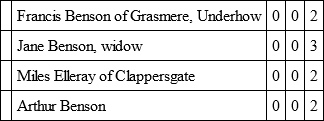

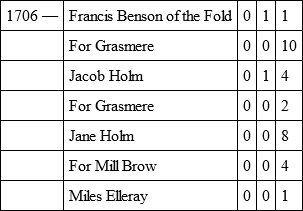

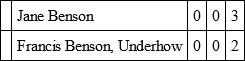

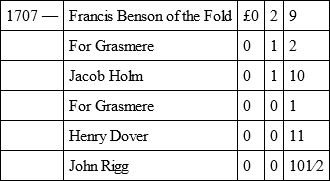

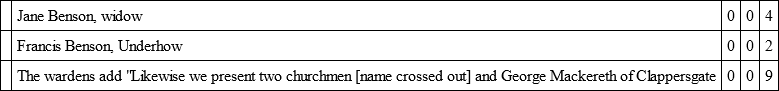

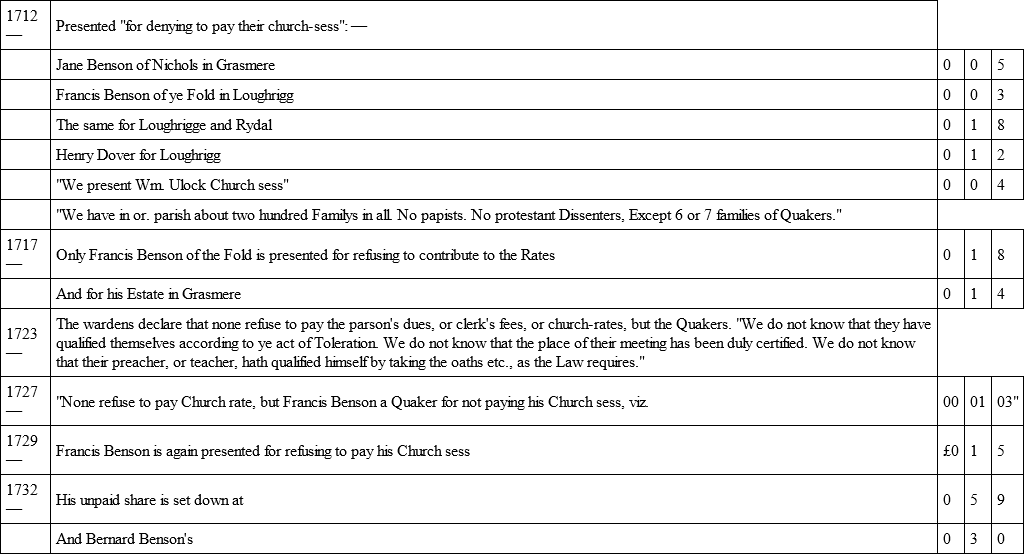

Presentments are only available from 1702. The following extracts give the names of the non-payers of the two townships. Those of Langdale would appear in their separate presentment: —

Loughrigg.

Grasmere.

Loughrigg.

Grasmere.

Loughrigg.

Grasmere.

This Francis Benson, the third Friend of his name at the Fold, is the last we know of. As the old families died out or dispersed, no new adherents of the sect appear to have arisen in the parish, and dissent ceased.

The only comment on non-conformity found in the registers occurs in the second volume (1687-1713). It runs: —

A perticular Register of some pretended Marryages of the people called Quakers within the parish of Grasmere As followeth —

But only two weddings from Great Langdale are set down. Also is entered: —

Jane daughter of John Grigge of Stile End in Great Langdale was baptized by A prebyterian minister the tenth day of Aprill Ano Dom 1710.

The "minister" so clearly obnoxious to the registrar may have been a visitor to the valley.

When a stranger entered the church in 1827 and asked the clerk if there were any Dissenters in the neighbourhood, he was told that there were none nearer than Keswick, where were some who called themselves Presbyterians; and of these the clerk professed so little knowledge that he hazarded the suggestion that they were a kind of "papishes." The clerk aforesaid was old George Mackereth,193 forgetful alike of the Colthouse Meeting-House and the small Baptist Chapel at Hawkshead Hill, built in 1678? For about the first clustered a few families who clung to the faith of their fathers; though the latter (of which little seems to be known) may have dropped out of use.

Dissent had never existed in Ambleside. The men of that town, who managed the affairs of their chapel, had no real leanings towards it, and the Restoration found them all churchmen again. The only man of the town-division who could be taxed as a non-communicant in 1675 was Roger Borwick, and he was a disreputable inn-keeper at Miller Bridge, a Roman Catholic who had once been a personal servant of the ill-fated heir of Squire John Fleming.

THE REGISTERS

The early registers are contained in three parchment books. The first measures 15 inches by 7, and has a thickness of 1 inch. It was re-bound recently in white vellum, and an expert has endeavoured to restore the almost vanished characters of the first page. The earliest legible entries are for January 1570-71. The sheets may have once got loose and some lost, for there is a complete gap between the years 1591-98, and another between 1604-11. There are minor gaps besides, which, perhaps, may be explained by the system of register keeping that obtained in these parts. A smaller book for entries was kept, called a pocket-register, in which the minister (or the clerk) noted down the ceremonies as they occurred; and these were copied from time to time into the larger book. It was a system that, in the hands of careless officials, produced nothing short of disaster, as far as parochial history is considered. The re-entry, long over-due, had often not been made, before the pocket-register was mis-placed or lost. In times of stress, like those of the plague-years, the church officials seem to have become paralized, and ceased to cope for months at a time with the registration of the dead. For instance, in the deadly year 1577, February, April, May and July are blank; eight burials are then entered for August, and none for the rest of the year. Again, next year, eight deaths are recorded for July, nine for September, and twelve for November, while the intervening and succeeding months are blank. This state of things continues through the years of oft-returning plague that followed, and through the long rectorate of John Wilson, diversified by the occasional loss of a page or a mysterious skip, e. g., in marriages there is a gap between the years 1583-4 and 1611 – more than 27 years.194

The first register-book is, therefore, a disappointing document, from which no satisfactory conclusions as to population or death-rate can be drawn, nor adequate information concerning families or individuals. The Hawkshead register-book is a complete contrast to this one, in neatness and fulness; and the scribe has marked with a cross all deaths from plague. Maybe the grammar-school there, with its master, affected favourably the records of the parish. In Grasmere the school was, after the Reformation, left in general to the parish clerk. This first book shows signs, like the Curate's Bible of Ambleside, of having been accessible to the scholars – no doubt while these were yet taught in the church; for experiments in penmanship and signatures occur on blank spaces, which were seized upon with avidity by the learner – parchment and paper being hard to come by.

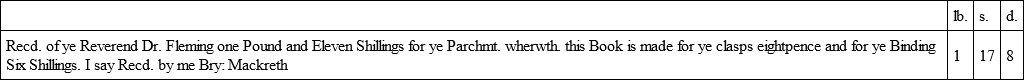

The condition of the third register-book is wholly satisfactory. It is in its original binding, but the clasps have gone. It measures 161⁄2 inches by 7, with a thickness of 3 inches. Its title runs, "Grasmere's Register Book, from May the 7th, A.D., 1713. Henry Fleming, D.D., Rector; Mr. Dudley Walker, Curate; Anthony Harrison, Parish Clerk." The book closes in December, 1812. As in the earlier volumes, the baptisms and marriages are written on the left page, and burials on the right. The first entry is a receipt from the man who furnished the book: —

June ye 21, 1713.

Some entries of confirmations were made in this volume. The first has caused considerable surprise, and it is of interest on three scores. It shows that the solemnization of the rite had been long neglected – the Bishop of Chester no doubt finding this remote parish of his diocese very inconvenient to reach, and relegating it on this occasion to his brother of Carlisle, who but recently was its rector. It likewise proves that the population was larger then than in the next century, and that the estimate of the number of communicants given on a preceding page was under, rather than over, stated. It illustrates the fact, besides, that the old forms would accommodate at least twice the number of the present benches.

October the 23, 1737A Confirmation was then holden at this Church by the Right Reverend Father in God Sr. George Fleming Baronet Lord Bishop of Carlisle at the instance of the Lord Bishop of Chester at which time and place About five Hundred Persons were Confirmed. [The next confirmation recorded is in 1862.]

An entry on the first page, in fine hand-writing, is likewise of interest, as showing that long after the Reformation, and even after the Prayer Book revision of 1662, the prohibition of the old Sarum Manual against marriages taking place during the three great feasts of Christmas, Easter and Penticost still had weight, though it could not be enforced, and that the rector – a stout churchman – desired its observance.

Marriages Prohibited from Advent Sunday till a Week after the Epiphany, from Septuagesima Sunday till a Week after Easter, from Ascension day till trinity Sunday; Secundum Dr. Comber.195

Curious entries, or any bearing upon local history, such as are frequent in some registers, are scarce in the Grasmere books. The law that commanded the use of woollen for shrouds, by way of propping up a declining industry, caused the usual amount of trouble here in the way of affidavits and entries.

Another enactment, that all sickly persons who presented themselves for cure by the Royal touch – a remedy much resorted to under the Stuarts – were to come armed with a parochial certificate,196 has left its trace here.

Wee the Rector and Churchwardens of the Parish of Grasmere in the County of Westmorland do hereby certify that David Harrison of the said Parish aged about fourteen years is afflicted as wee are credibly informed with the disease comonly called the Kings Evill; and (to the best of or knowledge) hath not hereto fore been touched by His Majesty for ye sd. In testimony whereof wee have here unto set or hands and seals the Fourth day of Feb: Ano Dom 1684.

Henry Fleming Rector.

John Benson

John Mallison Churchwardens.

Registered by John Brathwaite Curate.

This poor youth was probably of the Rydal stock of Harrisons, where several generations of Davids had flourished as statesmen, carriers and inn-keepers.197 The journey to London would be little to them.

The introduction of gunpowder into the slate quarries could not have long pre-dated the following entry: —

"Thomas Harrison of Weshdale [Wastdale?], wounded with the splinters of stone and wood the 29th of August last by the force of gunpowder was buryed September the 2nd. Ano Dom 1681."

An instance of longevity is given in 1674, when widow Elizabeth Walker, of Underhelme, "dyed at ye age of 107 years old."

But the entry that has caused the most comment is one that commemorates a boating disaster on Windermere Lake. Forty-seven persons were drowned, with some seven horses: "in one boate comeinge over from Hawkshead" on October 20th, 1635. Singularly enough, this is the only known record of an event with which tradition and later story has been busy. These affirm that the boat-load consisted of a wedding-party; also that the corpses were buried under a yew-tree in Windermere church-yard. If the catastrophe happened to the customery ferry, known as Great Boat, plying between Hawkshead Road and Ferry Nab, the interment would naturally be made at that church, though an unfortunate gap in the registers for the period prevents certainty on the point. But why was the event written down at Grasmere? It appears to have been inscribed by George Bennison, clerk and schoolmaster, who did not enter office till 1641. Had he the intention (unfortunately unfulfilled) of recording local history in the register-book? Could we suppose the Ambleside Fair for October 20th – an occasion of great resort only a few decades later – to have been in vogue before its charter was gained, the conjecture that the drowned folk had been attending the fair might be entertained.198 There were other passage-boats on the lake besides the Great one. In connection with the number drowned, it may be mentioned that ferry-boats were formerly of great size. Miss Celia Fiennes, who, about the year 1697, had occasion on her journey to cross the Mersey with her horses from Cheshire to Liverpool – a passage which occupied 11⁄2 hours – did it in a boat which, she says, would have held 100 people.199

Miss Helen Sumner has been, since 1906, engaged in a transcript of the first register-book. It is now complete, and it will be put into use instead of the old illegible volume, of which it is an absolutely accurate copy, done in fine modern script.

Miss Armitt was under the impression when writing of the Registers that the Second Register was missing, so consequently made no extracts from it. – Ed.

PRESENTMENTS, BRIEFS, AND CHARITIES

The Presentment for 1702 may be given fully as a specimen of the document which the wardens were bound to furnish at the Visitation of the Bishop or his emissary. A few extracts may be added, for the simplicity and shrewdness of some of the answers make them entertaining, as in the entire repudiation of an apparitor and his dues.

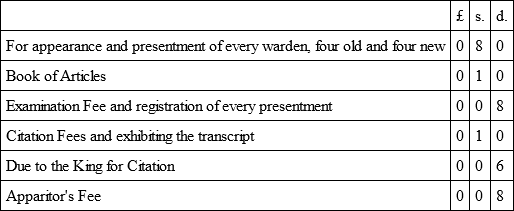

During Dr. Fleming's rectorate, a difference arose between the officials who controlled the finance department of the Visitation and the vestries of the parishes of Windermere and Grasmere.200 It was proposed by the latter to make one Presentment serve for the whole parish, mother-church and chapels together; and the rector of Grasmere stated that it was only through a mis-conception that separate Presentments had been made. This was a sound, economical plan for the parish, but it was firmly opposed (as was natural) by the higher officials, who affirmed that separate Presentments were the rule. The table of "ancient and justifiable fees" was given as follows: —

Also apparitors received at the Visitation a fee for carrying out books sent by the King and Council – as Thanksgiving Books, etc.; and for each of these he might claim a fee of 1s., which raised the sum total to be paid at a Visitation occasionally to 14s. or 15s. No wonder our wardens disclaimed all knowledge of the apparitor! For their consolation they were reminded that in other Jurisdictions the wardens were called to Visitations twice a year, which doubled the fees and expenses.