полная версия

полная версияSt. Peter, His Name and His Office, as Set Forth in Holy Scripture

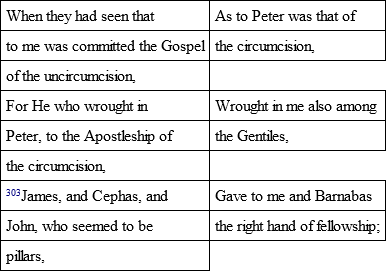

These last words lead us attentively to consider the passage which follows in S. Paul. At a subsequent period the zealots of the law had raised against him a report that the Gospel which he preached differed from that of the Twelve. At once to meet and silence such a calumny, he tells us that "after fourteen years, I went up again to Jerusalem, with Barnabas, taking Titus also with me. And I went up according to revelation, and," assigning the particular purpose, "conferred with them the Gospel which I preach among the Gentiles, but apart with them who seemed to be something; lest, perhaps, I should run, or had run, in vain." Then, having proved the identity of his doctrine with that of those who "seemed to be something," that is, Peter, James, and John, though to him they "added nothing," he specifies Peter among these, and proceeds to draw a singular parallel between, on the one hand, Peter, as accompanied by James and John, and himself, as working with Barnabas and Titus. If we set the clauses over against each other, this will be more apparent: —

Примечание 1303

where it would appear that James and John stand in the like relation to Cephas, as Barnabas and Titus, just before mentioned, to Paul. And S. Chrysostome, who, it must be remarked, reads Cephas, and not James, first, as do some manuscripts and many Fathers, observes, "where it was requisite to compare himself, he mentions Peter only, but were to call a testimony, he names three together and with praise, saying, 'Cephas, and James, and John, who seemed to be pillars.'" And further, Paul "shows himself to be of the same rank with them, and matches himself not with the rest, but with the leader, showing that each of them enjoyed the same dignity,"304 that is, of the Apostolic commission, and the divine cooperation. And Ambrosiaster explains the parallel: "Paul names Peter only, and compares him to himself, as having received the Primacy for the founding of the Church, he being in like manner elected to hold a Primacy in founding the Churches of the Gentiles, yet so that Peter, if occasion might be, should preach to the Gentiles, and Paul to the Jews. For both are found to have done both." And presently, "by the Apostles who were the more illustrious among the rest, whom for their stability he names pillars, and who were ever in the Lord's secret council, being worthy to behold His glory on the mount," (where Ambrosiaster confuses James, the brother of the Lord, with James the brother of John,) "by these he declares to have been approved the gift which he received from God, that he should be worthy to hold the Primacy in the preaching of the Gentiles, as Peter held it in the preaching of the circumcision. And as he assigns to Peter for companions distinguished men among the Apostles, so he joins Barnabas to himself; yet he claims to himself alone the grace of the Primacy as granted by God, like as to Peter alone it was granted among the Apostles.305

Now Baronius proves that the above words cannot be taken of a division of jurisdiction, and that the singular dignity of Peter is marked in them. "For as a mark of his excellence Christ Himself, who came to save all men, with whom there is no distinction of Jew and Greek, was yet called 'minister of the circumcision,' by Paul, (Rom. xv. 8,) a title of dignity, according to Paul's own words, for theirs was 'the adoption of children, and the glory, and the testament, and the giving of the law, and the service of God, and the promises,' while 'the Gentiles praise God for His mercy,' But just as Christ our Lord was so called minister of the circumcision, as yet to be the Pastor and Saviour of all, so Peter too was called the minister of the circumcision, in such sense as yet to be by the Lord constituted (Acts ix. 32,) pastor and ruler of the whole flock. Whence S. Leo, 'out of the whole world Peter alone is chosen to preside over the calling of all the Gentiles, and over all the Apostles, and the collected Fathers of the Church, so that though there be among the people of God many priests and many shepherds, yet Peter rules all by immediate commission, whom Christ also rules by Sovereign power.'"306

The parallel, then, drawn by Paul between himself and Peter, distinctly conveys that as he was superior to Barnabas and Titus, and used their cooperation, so was Peter among the Apostles, and specially the chief ones, James and John, as their leader and head. For what is the meaning of the words, "He who wrought in Peter to the Apostleship of the circumcision?" Was the Apostleship of the circumcision entrusted to Peter only? It needs no proof that it was also entrusted to James and John, nay, Paul himself immediately says so, "They gave to me and Barnabas the right hands of fellowship, that we should go unto the Gentiles, and they unto the circumcision." Why then does Paul so express himself as to intimate that the Gospel of the circumcision was given to Peter only? For the same reason that he said that to himself "was committed the Gospel of the uncircumcision," and that God "wrought in me also among the Gentiles." Now Barnabas likewise had been307separated by the Holy Ghost Himself for the Gentile mission; Barnabas, too, and Titus were discharging the office of ambassadors for Christ among the Gentiles: "that we," Paul says, not I, "should go to the Gentiles." The terms, therefore, used by Paul both of himself and Peter, do not exclude the rest, but express the superiority of the one named singly before the rest, as if he alone held the charge. Their fittest interpretation, then, will be, "The Apostles saw that the Gospel of the uncircumcision was no less given to me above the rest, than the Gospel of the circumcision to Peter above the rest; for He who wrought in Peter above the rest in the Gospel of the circumcision, wrought also in me above the rest in the Gospel of the uncircumcision." But what can set forth S. Peter's dignity more remarkably than to exhibit him in the same light of superiority among the original Apostles, as S. Paul was among S. Barnabas and his other fellow-workers?

Further confirmation of this is given by the argument with which he refutes the calumny urged against him of disagreement with the Apostles. For while he appeals to them in general, and to his union with them, he likewise specifies the point which favoured that union. It was the parallel between himself and Peter, as we have seen; it was the exact resemblance between his mission and that of Peter, which was the cause of their joining hands: they approve Paul's Apostleship because they see that it follows the type of Peter's.

And other words of Paul which follow, prove not only the point of his own cause, but the source of Peter's singular privileges. "But when Cephas was come to Antioch, I withstood him to the face, because he was to be blamed: for before that some came from James, he did eat with the Gentiles; but when they were come he withdrew, and separated himself, fearing them who were of the circumcision. And to his dissimulation the rest of the Jews consented, so that Barnabas also was led by them into that dissimulation. But when I saw that they walked not uprightly unto the truth of the Gospel, I said to Cephas before them all, If thou being a Jew livest after the manner of the Gentiles, and not as the Jews do, how dost thou compel the Gentiles to live as the Jews?" For why did Paul here censure Peter only? By his own account not only Peter, but the rest, and Barnabas himself amongst them, set apart as he was by the Holy Ghost to preach to the Gentiles, did not defend Christian liberty, as they ought to have done. Why, then, does he single out Peter among all these, resist him to the face, and so firmly censure all, in his person? No answer can be given but one: that by this dissembling of Peter the zealots of the law gathered double courage to press against Paul their calumny of dissension from Peter, and to infer that he had run in vain, from the indulgence which Peter showed; that Peter's authority with all was so great that his example drew the pastors and their flocks alike to his side, and that it was requisite to correct the members in the head. From this S. Chrysostome proves that it was really the Apostle Peter, which some, as we shall soon see, denied: "For to say, that I resisted him to the face, and to put this as a great thing, was to show that he had not reverenced the dignity of his person. But had he said it of another, that I resisted him to the face, he would not have put it as a great thing. Again, if it had been another Peter, his change would have not had such force as to draw the rest of the Jews with him. For he used no exhortation, nor advice, but merely dissembled, and separated himself, and that dissembling and separation had power to draw after him all the disciples, on account of the dignity of his person."308 Again, another writer of the fourth century tells us this: "Therefore he inveighs against Peter alone, in order that the rest might learn in the person of him who is the first."309 It was, then, Peter's primacy, and the necessity of agreeing with him thence arising, which led Paul to resist him publicly, and, disregarding the conduct of the rest, to direct an admonition to him alone. "So great," S. Jerome tells us, on these two passages, "was Peter's authority, that Paul in his epistle wrote, 'Then after three years I went to Jerusalem to see Peter, and I tarried with him fifteen days.' And again in what follows, 'After fourteen years I went up again to Jerusalem with Barnabas, taking Titus also with me. And I went up according to revelation, and conferred with them the Gospel which I preach among the Gentiles,' showing that he had no security in preaching the Gospel, unless it were confirmed by the sentence of Peter and those who were with him."310

But this passage,311 concerning the reprehension of S. Peter by S. Paul, has afforded so signal an instance "of the unlearned and unstable wresting Scripture to their own proper destruction,"312 that we must dwell a little longer upon it. First, the Gnostics and the Marcionites quoted it to accuse the Apostles of ignorance, and to favour their own claim to a progressive light. In Peter, they would have it, there was still a taint of Judaism. Next Porphyry, who "raged against Christ like a mad dog,"313 tried by this passage to weaken the authority of the Apostles, and to convict Paul of ambition and rashness, who censured the first of the Apostles and the leader of the band, not privately, but openly before all, as S. Chrysostome and S. Jerome tell us. Julian the apostate succeeded these, and tried, by means of Paul's contention with Peter, to bring discredit on the religion itself. For who, he asked, could value a religion whose chief teachers were guilty of hypocrisy, ignorance, and ambition? And in complete accordance with the spirit of these, all, who, since the sixteenth century, have attempted to impugn S. Peter's prerogatives, have rested their chief effort on the exaggeration and distortion of this reprehension. "This," says Baronius, "is the stone of stumbling, and rock of offence, on which a great number have dashed themselves. For those, who without any diligent consideration have superficially interpreted a difficult statement, have gone so far in their folly as either to accuse Paul of rashness for having inveighed against Peter not merely with freedom, but wantonness, or to calumniate Peter as a hypocrite, for acting with dissimulation; or to condemn both, for not agreeing in the same rule of faith."314

In most remarkable contrast with these stand out three several interpretations, which prevailed in early times, all differing from each other in points, but all equally careful to maintain the dignity of Peter, and to clear up the conduct of Paul. First, from S. Clement of Alexandria in the second century up to S. Chrysostome in the fourth, we find a number of Greek writers asserting that it was not the Apostle Peter, who was here meant, but another; S. Jerome gives their reasons thus: "there are those who think that Cephas, whom Paul here writes that he resisted to the face, was not the Apostle Peter, but another of the seventy disciples so called, and they allege that Peter could not have withdrawn himself from eating with the Gentiles, for he had baptized Cornelius the centurion, and on his ascending to Jerusalem, being opposed by those of the circumcision who said, 'why hast thou entered in to men uncircumcised, and eaten with them?' after narrating the vision, he terminates his answer thus: 'If, then, God hath given to them the same grace as to us who believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I should withstand God?' On hearing which they were silent, and glorified God, saying: 'Therefore to the Gentiles, also, God hath given repentance unto life.' Especially as Luke, the writer of the history, makes no mention of this dissension, nor even says that Peter was at Antioch with Paul; and occasion would be given to Porphyry's blasphemies, if we could believe either that Peter had erred, or that Paul had impertinently censured the prince of the Apostles."315

But this interpretation, contrary both to internal evidence and to early tradition, and suggested only by the anxiety to defend S. Peter's dignity, did not prevail. Another succeeded, supported by S. Chrysostome, S. Cyril, and the greatest Greek commentators, and for a long time by S. Jerome, even more remarkably opposed to the apparent sense of the passage, and only, as it would seem, dictated by the same desire to defend the dignity of S. Peter, and the conduct of S. Paul. Admitting that it was really Peter who was here mentioned, they maintained that it was not a real dissension between the two Apostles, but apparent only, and arranged both by the one and the other, to terminate the question more decidedly. S. Chrysostome316 sets forth at great length this opinion: "Do you see," says he, "how S. Paul accounts himself the least of all saints, not of Apostles only? Now he who was so disposed with respect to all, both knew how great a prerogative Peter ought to enjoy, and reverenced him most of all men, and was disposed towards him as he deserved. And this is a proof. The whole earth was looking to Paul; there rested on his spirit the solicitude for the Churches of all the world. A thousand matters engaged him every day; he was besieged with appointments, commands, corrections, counsels, exhortations, teachings, the administration of endless business; yet giving up all these, he went to Jerusalem. And there was no other occasion for this journey save to see Peter, as he says himself: 'I went up to Jerusalem to visit Peter.' Thus he honoured him, and preferred him to all men." Suspecting, too, that an accusation against Peter's unwavering faith, might be brought from the words, "fearing those of the circumcision," he breaks out, 'What say you? Peter fearful and unmanly? Was he not for this called Peter, that his faith was immovable? What are you doing, friend? Reverence the name given by the Lord to the disciple. Peter fearful and unmanly! Who will endure you saying such things?'"

Now compare317 together these two interpretations of the Greek Fathers with that of the reformers and their adherents since the sixteenth century. A more complete antagonism of feelings and principles cannot be conceived. I. There is not a Greek Father who does not infer the singular authority of Peter from the first and second chapter of the epistle to the Galatians. There is not an adherent of the reformers who does not trust that he can draw from those same chapters matter to impugn S. Peter's Primacy. II. The Greek Fathers anxiously search out every point which may conduce to Peter's praise. The adherent of the reformers suppresses all such, and seems not to see them. III. If anything in Paul's account seems at first sight to tell against Peter's special dignity, the Greek Fathers are studious carefully to remove it; the adherents of the reformers to exaggerate it. IV. The Greek Fathers prefer slightly to force the obvious meaning of the words, and to desert the original interpretation, rather than set Apostles at variance with each other, or admit that Peter, the chief of the Apostles, was not treated with due deference. The adherents of the reformers intensify everything, take it in the worst sense, and are the more at home, the more bitterly they inveigh against Peter.

Now turn to the third interpretation, that of the Latin Fathers. They admit both that it was Peter and that it was a real dissension, but they are as anxious as the Greek to defend Peter's dignity. Thus Tertullian:318 "If Peter was blamed – certainly it was a fault of conduct, not of preaching." And Cyprian:319 "not even Peter, whom first the Lord chose, and upon whom He built His Church, when afterwards Paul disagreed with him respecting circumcision, claimed aught proudly, or assumed aught arrogantly to himself, saying that he held the Primacy, and that obedience rather was due to him by those younger and later." And Augustine: "Peter himself received with the piety of a holy and benignant humility what was with advantage done by Paul in the freedom of charity. And so he gave to posterity a rarer and a holier example, that they should not disdain, if perchance they left the right track, to be corrected even by their youngers, than Paul, that even inferiors might confidently venture to resist superiors, maintaining brotherly charity, in the defence of evangelical truth. For better as it is on no occasion to quit the proper path, yet much more wonderful and praiseworthy is it, willingly to accept correction, than boldly to correct deviation. Paul then has the praise of just liberty, and Peter of holy humility: which, so far as seems to me according to my small measure, had been a better defence against the calumnies of Porphyry, than the giving him greater occasion of finding fault: for it would be a much more stinging accusation that Christians should with deceit either write their epistles, or bear the mysteries of their God."320

Now, to see the321 fundamental opposition between the Greek and Latin Fathers, and the reformers, let us observe that, though there are three ancient interpretations of this passage, differing from each other, the first denying that the Cephas so reprehended by Paul, was the chief of the Apostles, the second affirming this, but reducing the whole contention to an arrangement of prudence between the two Apostles, and the third maintaining the reality of the reprehension, yet all three have in common the reconciling Peter's chief dignity with the reprehension of him, and the two latter, besides, are much more careful to admire his modesty, than Paul's liberty, and make the most of every point in the narration setting forth Peter's Primacy. On the other hand the reformers use this reprehension as their sharpest weapon against his authority, praise Paul's liberty to the utmost in order to depress that authority, hunt out everything against Peter, and pass over everything for him. It is equally evident that their motive in this runs counter to the faith universal in the Church during the first four centuries; and that their inference cannot be accepted without rejecting all Christian antiquity, and the very sentiments expressed by Paul himself, as we have seen, towards Peter.

But as to the reprehension itself, it would seem to have been not on a point of doctrine at all, but of conduct. S. Peter had long ago both admitted the Gentiles into the Church, and declared that they were not bound to the Jewish law. But out of regard to the feelings of the circumcised converts, he pursued a line of conduct at Antioch, which they mistook to mean an approval of their error, and which needed, therefore, to be publicly cleared up. Accordingly, Peter's fault, if any there were, amounted to this, that having, with the best intention, done what was not forbidden, he had not sufficiently foreseen what others would thence infer contrary to his own intention. Can this be esteemed either a dogmatic error, or a proof of his not holding supreme authority? But the event being injurious, and contrary to the truth of the Gospel, why should not Paul admonish Peter concerning it? But very remarkable it is, that he quotes S. Peter's own example and authority, opposes the antecedent to the consequent fact, and maintains Gospel liberty by Peter's own conduct. S. Chrysostome remarked this. "Observe his prudence. He said not to him, Thou dost wrong, in living as a Jew, but he alleges his former mode of living, that the admonition and the counsel may seem to come not from Paul's mind, but from the judgment of Peter already expressed. For had he said, Thou dost wrong to keep the law, Peter's disciples would have blamed him, but now, hearing that this admonition and correction came not from Paul's judgment, but that Peter himself so lived, and held in his mind this belief, whether they would, or would not, they were obliged to be quiet."322

CHAPTER VII.

S. PETER'S PRIMACY INVOLVED IN THE FOURFOLD UNITY OF CHRIST'S KINGDOM

The doctrine323 of S. Paul has brought us to a most interesting point of the subject, what, namely, is the principle of unity in the Church. A short consideration of this will shew us how the office of S. Peter enters into and forms part of the radical idea of the Church, so that the moment we profess our belief in one holy Catholic Church, the belief is likewise involved in that Primacy of teaching and authority which makes and keeps it one.

The principle of unity, then, is no other than "the Word made flesh: " that divine Person who has for ever joined together the Godhead and the Manhood. Thus, S. Paul speaks to us of God "having made known to us the mystery of His will, according to His good pleasure, which He purposed in Himself, in the dispensation of the fulness of times, to gather together under one head all things in Christ, both which are in heaven and which are on earth:" at whose resurrection, "He set all things under His feet, and gave Him to be head over all to the Church, which is His body, the fulness of Him who filleth all in all." And again, "the head of every man is Christ; – and the head of Christ is God." "And we being many are one body in Christ, and every one members one of another:"324 as, again, he sets forth at length in the 12th chapter of the First Epistle to the Corinthians, calling that one body by the very name of Christ.

With one voice the ancient Fathers325 exult in this as the great purpose of His Incarnation. "The work," says S. Hippolytus,326 "of His taking a body, is the gathering up into one head of all things unto Him." "The Word Man," says S. Irenæus,327 "gathering all things up into Himself, that as in super-celestial, and spiritual, and invisible things, the Word of God is the chief, so also in visible and corporeal things He may hold the chiefship, assuming the Primacy to Himself, and joining Himself as Head to the Church, may draw all things to Himself, at the fitting time." And again, "The Son of God was made Man among men, to join the end to the beginning, that is, man to God;" or, as Tertullian says,328 "that God might shew that in Himself was the evolution of the beginning to the end, and the return of the end to the beginning." And Œcumenius, "Angels and men were rent asunder; God then joined them, and made them one through Christ." S. Gregory Thaumaturgus breaks out, "Thou art He that didst bridge over heaven and earth by Thy sacred body." And Augustine,329 "Far off He was from us, and very far. What, so far off as the creature and the Creator? What, so far off as God and man? What, so far off as justice and iniquity? What, so far off as eternity and mortality? See how far off was 'the Word in the beginning, God with God, by whom all things were made.' How, then, was He made nigh, that He might be as we, and we in Him? 'The Word was made flesh.'" "Man, being assumed, was taken into the nature of the Godhead," says S. Hilary:330 and S. Chrysostome,331 "He puts on flesh, that He who cannot be held may be holden: " "dwelling with us," says Gregory332 of Nazianzum, "by interposing His flesh as a veil, that the incomprehensible may be comprehended." "For since," adds S. Cyril,333 "man's nature was not capable of approaching the pure and unmixed glory of the Godhead, because of its inherent weakness, for our use the only-begotten one put on our likeness." "In the assumption of our nature," says S. Leo,334 "He became to us the step, by which through Him we may be able to mount unto Him: " "the descent of the Creator to the creature is the advance of believers to things eternal: " and, "it is not doubtful that man's nature has been taken into such connection by the Son of God, that, not only in that Man who is the first-born of all creation, but even in all His saints, there is one and the same Christ: and as the Head cannot be divided from the limbs, so neither the limbs from the Head. For though it belong not to this life, but to that of eternity, that God be all in all, yet even now He is the undivided inhabitant of His temple, which is the Church." For all the above is contained in our Lord's own words, "that they all may be one, as Thou, Father, in Me, and I in Thee," on which S. Athanasius335 says, "that all, being carried by Me, may be all one body and one spirit, and reach the perfect man: " – "for, as the Lord having clothed Himself in a body, became man, so we men are deified by the Word, being assumed through His flesh." S. Gregory,336 of Nyssa, has unfolded this idea thus: "since from no other source but from our lump was the flesh which received God, which, by the resurrection, was together with the Godhead exalted; just as in our own body the action of one organ of sense communicates sympathy to all that which is united with the part, so, just as if the whole nature (of man) were one living creature, the resurrection of a part passes throughout the whole, being communicated from the part to the whole, according to the nature's continuity and union." And another,337 interpreting the words, "that they all may be one," "thus I will, that they being drawn into unity, may be blended with each other, and becoming as one body, may all be in Me, who carry all in that one temple which I have assumed; the temple, namely, of His Body." And lastly, S. Hilary338 deduces this not only from the Incarnation, but from the Blessed Eucharist. "For, if the Word be really made flesh, and we really receive the Word as flesh, in the food of the Lord, how is He not to be thought to remain in us naturally, since, both in being born a man, He assumed the nature of our flesh, never to be severed from Him, and has joined the nature of His flesh to the eternal nature under the sacrament of the flesh to be communicated to us."