Полная версия

The British Are Coming

“It seemed as if men came down from the clouds,” another witness recalled. Some took posts on the two bridges spanning the Concord River, which looped west and north of town. Most made for the village green or Wright Tavern, swapping rumors and awaiting orders from Colonel James Barrett, the militia commander, a sixty-four-year-old miller and veteran of the French war who lived west of town. Dressed in an old coat and a leather apron, Barrett carried a naval cutlass with a plain grip and a straight, heavy blade forged a generation earlier in Birmingham. His men were tailors, shoemakers, smiths, farmers, and keepers from Concord’s nine inns. But the appearance of tidy prosperity was deceiving: Concord was suffering a protracted decline from spent land, declining property values, and an exodus of young people, who had scattered to the frontier in Maine or New Hampshire rather than endure lower living standards than their elders had enjoyed. This economic decay, compounded by the Coercive Acts and British political repression, made these colonial Americans anxious for the future, nostalgic for the past, and, in the moment, angry.

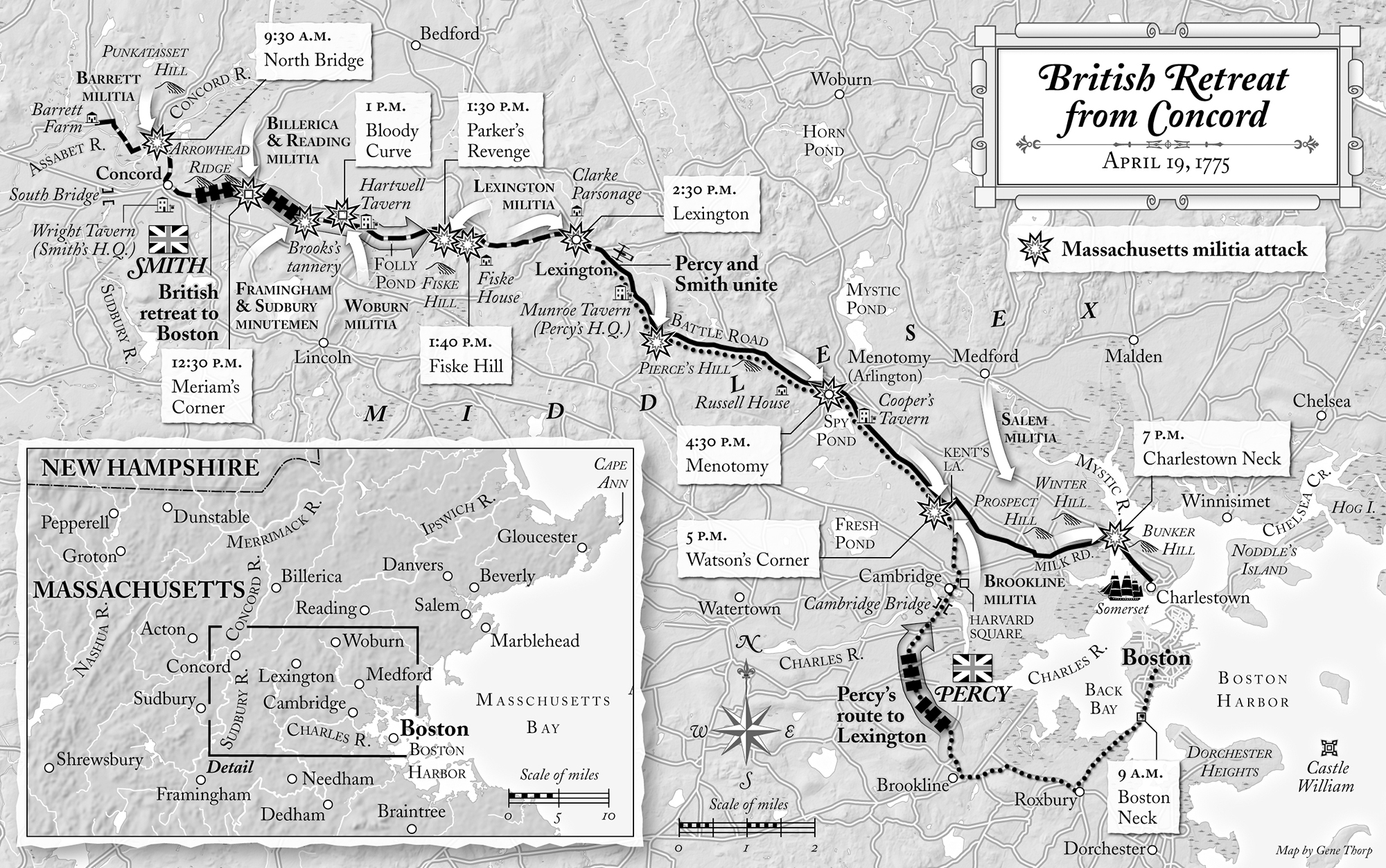

Sometime before eight a.m., perhaps two hundred impatient militiamen headed for Lexington to the rap of drums and the trill of fifes. Twenty minutes later, eight hundred British soldiers hove into view barely a quarter mile away, like a scarlet dragon on the road near the junction known as Meriam’s Corner. “The sun shined on their arms & they made a noble appearance in their red coats,” Thaddeus Blood, a nineteen-year-old minuteman, later testified. “We retreated.”

They fell back in an orderly column, as if leading an enemy parade into Concord, the air vibrant with competing drumbeats. “We marched before them with our drums and fifes going and also the British drums and fifes,” militiaman Amos Barrett recalled. “We had grand music.” Past the meetinghouse the militia marched, past the liberty pole that had been raised as an earnest of their beliefs. A brief argument erupted over whether to make a stand in the village—“If we die, let us die here,” urged the militant minister William Emerson—but most favored better ground on the ridgeline a mile north, across the river. Colonel Barrett agreed, and ordered them to make for North Bridge. Concord was given over to the enemy.

The British brigade wound past Abner Wheeler’s farm, and the farms of the widow Keturah Durant and the spinster seamstress Mary Burbeen and then the widow Olive Stow, who had sold much of her land, along with a horse, cows, swine, and salt pork, to pay her husband’s debts when he’d died, three years earlier. They strode past the farms of Olive’s brother, Farwell Jones, and the widow Rebecca Fletcher, whose husband also had died three years before, and the widower George Minot, a teacher with three motherless daughters, who was not presently at home because he was the captain of a Concord minute company. Into largely deserted Concord the regulars marched, in search of feed for the officers’ horses and water for the parched men. From Burial Ground Hill, Smith and Pitcairn studied their hand-drawn map and scanned the terrain with a spyglass.

Gage’s late intelligence was accurate: in recent weeks, most military stores in Concord had been dispersed to nine other villages or into deeper burrows of mud and manure. Regulars seized sixty barrels of flour found in a gristmill and a malt house, smashing them open and powdering the streets. They tossed five hundred pounds of musket balls into a millpond, knocked the trunnions from several iron cannons found in the jail yard, chopped down the liberty pole, and eventually made a bonfire of gun carriages, spare wheels, tent pegs, and a cache of wooden spoons. The blaze briefly spread to the town hall, until extinguished by a bucket brigade of regulars and villagers.

With the pickings slim in Concord, Colonel Smith ordered more than two hundred men under Captain Lawrence Parsons to march west toward Colonel Barrett’s farm, two miles across the river. Perhaps they would have better hunting there.

Since 1654, a bridge had spanned the Concord River just north of the village. The current structure, sixteen feet wide and a hundred feet long, had been built for less than £65 in 1760 by twenty-six freemen and two slaves, using blasting powder and five teams of oxen. The timber frame featured eight bents to support the gracefully arcing deck, each with three stout piles wedged into the river bottom. Damage from seasonal floods required frequent repairs, and prudent wagon drivers carefully inspected the planks before crossing. A cobbled causeway traversed the marshy ground west of the river.

Seven British companies crossed the bridge around nine that Wednesday morning, stumping past stands of black ash, beech, and blossoming cherry. Dandelions brightened the roadside, and the soldiers’ faces glistened with sweat. Three companies remained to guard the span, while the other four continued with Captain Parsons to the Barrett farm, where they would again be disappointed: “We did not find so much as we expected,” an ensign acknowledged. A few old gun carriages were dragged from the barn, but searchers failed to spot stores hidden under pine boughs in Spruce Gutter or in garden furrows near the farm’s sawmill.

The five Concord militia companies had taken post on Punkatasset Hill, a gentle but insistent slope half a mile north of the bridge. Two Lincoln companies and two more from Bedford joined them, along with Captain Davis’s minute company from Acton, bringing their numbers to perhaps 450, a preponderance evident to the hundred or so redcoats peering up from the causeway; one uneasy British officer estimated the rebel force at fifteen hundred. On order, the Americans loaded their muskets and rambled downhill to within three hundred yards of the enemy. A militia captain admitted feeling “as solemn as if I was going to church.”

Solemnity turned to fury at the sight of black smoke spiraling above the village: the small pyre of confiscated military supplies was mistaken for British arson. Lieutenant Joseph Hosmer, a hog reeve and furniture maker, was described as “the most dangerous man in Concord” because young men would follow wherever he led. Now Hosmer was ready to lead them back across the bridge. “Will you let them burn the town down?” he cried.

Colonel Barrett agreed. They had waited long enough. Captain Davis was ordered to move his Acton minutemen to the head of the column—“I haven’t a man who’s afraid to go,” Davis replied—followed by the two Concord minute companies; their bayonets would help repel any British counterattack. The column surged forward in two files. Some later claimed that fifers tootled “The White Cockade,” a Scottish dance air celebrating the Jacobite uprising of 1745. Others recalled only silence but for footfall and Barrett’s command “not to fire first.” The militia, a British soldier reported, advanced “with the greatest regularity.”

Captain Walter Laurie, commanding the three light infantry companies, ordered his men to scramble back to the east side of the bridge and into “street-firing” positions, a complex formation designed for a constricted field of fire. Confusion followed, as a stranger again commanded strangers. Some redcoats braced themselves near the abutments. Others spilled into an adjacent field or tried to pull up planks from the bridge deck.

Without orders, a British soldier fired into the river. The white splash rose as if from a thrown stone. More shots followed, a spatter of musketry that built into a ragged volley. Much of the British fire flew high—common among nervous or ill-trained troops—but not all. Captain Davis of Acton pitched over dead, blood from a gaping chest wound spattering the men next to him. Private Abner Hosmer also fell dead, killed by a ball that hit below his left eye and blew through the back of his neck. Three others were wounded, including a young fifer and Private Joshua Brooks of Lincoln, grazed in the forehead so cleanly that another private concluded that the British, improbably, were “firing jackknives.” Others knew better. Captain David Brown, who lived with his wife, Abigail, and ten children two hundred yards uphill from the bridge, shouted, “God damn them, they are firing balls! Fire, men, fire!” The cry became an echo, sweeping the ranks: “Fire! For God’s sake, fire!” The crash of muskets rose to a roar.

“A general popping from them ensued,” Captain Laurie later told General Gage. One of his lieutenants had reloaded when a bullet slammed into his chest, spinning him around. Three other lieutenants were wounded in quick succession, making casualties of half the British officers at the bridge and ending Laurie’s fragile control over his detachment. Redcoats began leaking to the rear, and soon all three companies broke toward Concord, abandoning some of their wounded. “We was obliged to give way,” an ensign acknowledged, “then run with the greatest precipitance.” Amos Barrett reported that the British were “running and hobbling about, looking back to see if we was after them.”

Battle smoke draped the river. Three minutes of gunplay had cost five American casualties, including two dead. For the British, eight were wounded and two killed, but another badly hurt soldier, trying to regain his feet, was mortally insulted by minuteman Ammi White, who crushed his skull with a hatchet.

A peculiar quiet descended over what the poet James Russell Lowell would call “that era-parting bridge,” across which the old world passed into the new. Some militiamen began to pursue the fleeing British into Concord, but then veered from the road to shelter behind a stone wall. Most wandered back toward Punkatasset Hill, bearing the corpses of Davis and Abner Hosmer. “After the fire,” a private recalled, “everyone appeared to be his own commander.”

Colonel Smith had started toward the river with grenadier reinforcements, then thought better of it and trooped back into Concord. The four companies previously sent with Captain Parsons to Barrett’s farm now trotted unhindered across the bridge, only to find the dying comrade mutilated by White’s ax, his brains uncapped. The atrocity grew in the retelling: soon enraged British soldiers claimed that he and others had been scalped, their noses and ears sliced off, their eyes gouged out.

As Noah Parkhurst from Lincoln observed moments after the shooting stopped, “Now the war has begun and no one knows when it will end.”

No fifes and drums would play the British back to Boston. From his command post in Wright Tavern, Smith, described by one of his lieutenants as “a very fat heavy man,” moved with unwonted agility in organizing the retreat. Badly wounded privates would be left to rebel mercy, but horse-drawn chaises for injured officers were wheeled out from Concord’s barns and stables. Troops filled their canteens, companies again arranged themselves in march order, and a final round of food and brandy was tossed back. Before noon the red procession headed east, silent and somber, every man aware that eighteen miles of danger lay ahead.

The first mile proved almost tranquil. The road here was wide enough—four rods, or sixty-six feet—for the troops to march eight abreast, in a column stretching three hundred yards or more. Using tactics honed during years of combat in North American woodlands, scores of light infantry flankers swept through the tilled fields and apple orchards, stumbling over frost-heaved rocks while searching for rebel ambushers. “The country was an amazing strong one, full of hills, woods, stone walls, &c.,” Lieutenant Barker of the King’s Own would tell his diary. “They were so concealed there was hardly any seeing them.”

But the rebels were there. Arrowhead Ridge loomed above the north side of the road, offering a sheltered corridor through the Great Fields for hundreds of militiamen hurrying from North Bridge to Meriam’s Corner. Here the road narrowed to a causeway across boggy ground, canalizing and slowing the column. Skirmishers in slouch hats could be seen loping behind outbuildings and across the pastures and meadows. British soldiers wheeled and fired, but again threw their shot high. “This ineffectual fire gave the rebels more confidence,” one officer observed. A return volley killed two redcoats and wounded several more. Some officers dismounted to be less conspicuous; the morning had demonstrated how American marksmen—“with the most unmanly barbarity,” a redcoat complained—already had begun targeting those with shiny gorgets at their necks and the bright vermilion coats commonly worn by the higher ranks.

Now the running gun battle began in earnest, with crackling musketry and spurts of smoke and flame. The provincial ranks swelled to a thousand, twelve hundred, fifteen hundred, more by the hour—“monstrous numerous,” a British soldier would write to his mother. The road—Battle Road, as it would be remembered—angled past Joshua Brooks’s tannery; the smell of tannins rose from the pits, drying racks, and currier shop, and a sharper odor wafted from the nearby slaughterhouse that sluiced offal into Elm Brook. Just to the east, past where the wetlands had been ditched and drained to create a hay meadow, the road began to climb through a cut made in the brow of a wooded hill, then nearly doubled back on itself in a hairpin loop soon known as the Bloody Curve. Here was “a young growth of wood well-filled with Americans,” a minuteman wrote. “The enemy was now completely between two fires.”

Plunging fire gashed the column; grazing fire raked it. Men primed, loaded, and shot as fast as their fumbling hands allowed. A great nimbus of smoke rolled across the crest of the hill. Bullets nickered and pinged, and some hit flesh with the dull thump of a club beating a heavy rug. Militiamen darted from behind stone walls to snatch muskets and cartridge boxes from eight dead redcoats and several wounded who lay writhing in the Bloody Curve. One regular later acknowledged in a letter home that the rebels “fought like bears.” An American private reported seeing a wounded grenadier stabbed repeatedly by passing militiamen so that “blood was flowing from many holes in his waistcoat.” He later reflected, “Our men seemed maddened with the sight of British blood, and infuriated to wreak vengeance on the wounded and helpless.”

More vengeance lurked a mile and a half ahead. Captain John Parker’s company had suffered seventeen casualties in Lexington eight hours earlier, but Parker and his men—perhaps a hundred or more—were keen to fight again. Two miles west of the Common, they dispersed above a granite outcrop in a five-acre woodlot thick with hardwood—hickory, beech, chestnut, red and white oak—and huckleberry bushes. Battle noise drifted from the west, and around two p.m. the thin red line came into view six hundred yards down Battle Road, moving briskly despite more than sixty wounded, not to mention the two dozen dead already left behind. A small bridge at a sharp bend in the road again constricted the column, and as the British vanguard approached within forty yards, the rebels fired. Bullets struck Colonel Smith in the thigh and Captain Parsons in the arm. Major Pitcairn galloped forward to take command as redcoats sprayed the woodlot with lead slugs. When enemy soldiers began to bound up both flanks, Parker and his men turned and scampered through the trees, drifting toward Lexington to join other lurking ambuscades.

The “plaguey fire,” as one British captain called it, now threatened the column with annihilation. “I had my hat shot off my head three times,” a soldier later reported. “Two balls went through my coat, and carried away my bayonet from my side.” Gunfire seemed to swarm from all compass points at Bloody Bluff and, five hundred yards farther on, at Fiske Hill. Pitcairn’s horse threw him to the ground, then cleared a wall and fled into the rebel lines. The major wrapped up his injured arm and pressed on. Ensign Jeremy Lister was shot through the right elbow; a surgeon’s mate extracted the ball from under his skin, but a half dozen bone fragments would later be removed, some the size of hazelnuts.

The combat grew even more ferocious and intimate at Ebenezer Fiske’s house, still thirteen miles from Boston Harbor. James Hayward, a twenty-five-year-old teacher, had left his father’s farm in Acton that morning with a pound of powder and forty balls. At Fiske’s well, he abruptly encountered a British soldier. Both fired. The redcoat died on the spot; Hayward would linger for eight hours before passing, shards of powder horn driven into his hip by the enemy bullet. Several wounded British soldiers were left by their comrades in the Fiske parlor, and there they died.

“Our ammunition began to fail, and the light companies were so fatigued with flanking they were scarce able to act,” Ensign Henry De Berniere later wrote. “We began to run rather than retreat.” Officers tried to force the men back into formation, but “the confusion increased rather than lessened.” Hands and faces were smeared black from the greasy powder residue on ramrods; tiny powder burns from firelock touchholes flecked collars. The ragged procession entered Lexington, with the blood-streaked Common on the left. Officers again strode to the front of the column, brandished their weapons, and “told the men if they advanced they should die,” De Berniere added.

And then, like a crimson apparition, more than a thousand redcoats appeared on rising ground half a mile east of the village: three infantry regiments of the 1st Brigade and a marine battalion, sent from Boston as reinforcements. Smith’s beleaguered men gave a hoarse shout and pelted forward into the new British line, “their tongues hanging out of their mouths, like those of dogs after a chase,” as a later account described them. Wounded men collapsed under the elm trees or crowded into Munroe Tavern, sprawling across the second-floor dance hall or in bunks normally rented by passing drovers. To the delight of those rescued, and the dismay of the insurgents close on their heels, two Royal Artillery guns began to boom near the tavern, shearing tree limbs around the Common and punching a hole in Reverend Clarke’s meetinghouse. Gunners in white breeches with black spatterdashes swabbed each bore with a sponge, then rammed home another propellant charge and 6-pound ball. Sputtering portfire touched the firing vents and the guns boomed again with great belches of white smoke. Cast-iron shot skipped across the ground a thousand yards or so downrange, then skipped again with enough terrifying velocity to send every militiaman—under British artillery fire for the first time ever—diving for cover.

Overseeing this spectacle from atop his white charger, splendidly uniformed in scarlet, royal blue, and gold trim, Brigadier Hugh Earl Percy could only feel pleased with his brigade and with himself. “I had the happiness,” he would write his father, the Duke of Northumberland, on the following day, “of saving them from inevitable destruction.” Heir to one of the empire’s greatest fortunes and a former aide-de-camp to George III, Lord Percy at thirty-two was spindly and handsome, with high cheekbones, alert eyes, and a nose like a harpoon blade. As a member of Parliament, he at times had opposed the government’s policies, including the coercive measures against Massachusetts. As a professional soldier, he was capable, popular—the £700 spent from his own pocket to transport his soldiers’ families to Boston helped—and a diligent student of war, sometimes citing Frederick the Great, whose maxim on artillery was proved here in Lexington: “Cannon lends dignity to what might otherwise be a vulgar brawl.”

A year in New England had expunged whatever theoretical affection Percy held for the colonists, whom he now considered “extremely violent & wrong-headed,” if not “the most designing, artful villains in the world.” To a friend in England he wrote, “This is the most beautiful country I ever saw in my life, & if the people were only like it, we should do very well.… I cannot but despise them completely.” Now he was killing them.

Two blunders early in the day had already marred the rescue mission. Gage’s letter directing the 1st Brigade to muster at four a.m. on the Common was carelessly mislaid for several hours. Then the marines failed to get word—the order was addressed to Major Pitcairn, who had long departed Boston—causing further delays. At nine a.m., five hours late, Percy’s column had surged across Boston Neck. “Not a smiling face was among them,” a clergyman reported. “Their countenances were sad.” To lift spirits, fifers played a ditty first heard in a Philadelphia comic opera in 1767, with lyrics since improvised by British soldiers:

Yankee Doodle came to town

For to buy a firelock;

We will tar and feather him

And so we will John Hancock.

Not until one p.m., after passing the village of Menotomy, five miles from Lexington, did Percy first get word that Smith’s beleaguered expedition was retreating in mortal peril. By that time, a third mishap was playing out behind him. Desperate to make speed from Boston, Percy had declined to take a heavy wagon loaded with 140 extra artillery rounds; until reprovisioned, his gunners would make do with the twenty-four rounds carried for each 6-pounder in their side boxes, just as each infantryman would make do with his thirty-six musket cartridges. Two supply wagons had eventually followed the column only to be ambushed by a dozen “exempts”—men too old for militia duty—at an old cider mill across from the Menotomy meetinghouse. Two soldiers and four horses were killed, and several other redcoats were captured after reportedly tossing their muskets into Spy Pond. Rebels dragged the carcasses into a field, hid the wagons in a hollow, and swept dust over bloodstains on the road.

At three-fifteen p.m., Percy ordered his troops, now eighteen hundred strong, back to Boston. The Royal Welch Fusiliers formed a rear guard, and Smith’s exhausted men tucked in among their fresher comrades. The wounded hobbled as best they could or rode on gun barrels or the side boxes, spilling off whenever gunners unlimbered to hurl more iron shot. Percy was unaware that his supply train had been bushwhacked and that rebel numbers were approaching four thousand as companies from the outer counties arrived. Despite those dignified cannons, he was in for a vulgar brawl.

Looting began even before the column cleared Lexington. In light infantry slang, “lob” meant plunder taken without opposition; “grab” was booty taken by force. “There never was a more expert set than the light infantry at either grab, lob, or gutting a house,” a British officer later acknowledged. Lieutenant Barker complained in his diary that soldiers on the return march “were so wild and irregular that there was no keeping ’em in any order.… The plundering was shameful.” Sheets snatched from beds served as peddler’s packs to carry beaver hats, spinning wheels, mirrors, goatskin breeches, an eight-day clock, delftware, earrings, a Bible with silver clasps, a dung fork. “Many houses were plundered,” Lieutenant Mackenzie wrote. “I have no doubt this enflamed the rebels.… Some soldiers who stayed too long in the houses were killed in the very act of plundering.”

Every mile brought heavier fire. “We were attacked on all sides,” wrote Captain Glanville Evelyn, whose King’s Own company accompanied Percy, “from woods and orchards and stone walls, and from every house on the road.… They are the most absolute cowards on the face of the earth.” The day’s bloodiest fighting erupted in Menotomy—street to street, house to house, room to room. Here twenty-five Americans and forty British would die, with scores more wounded. “All that were found in the houses,” Lieutenant Barker wrote, “were put to death.”

Over a hundred British bullets perforated Cooper’s Tavern while the innkeeper and his wife cowered in the cellar. Two unarmed patrons were killed upstairs, according to a deposition, “their brains dashed across the floor and walls.” At the Jason Russell house, Danvers militiamen piled up shingles as a breastwork in the yard only to be outflanked and caught in a British cross fire. Some fled into the house as balls poured through the windows, “making havoc of glass.” Russell was shot on his doorstep and bayoneted nearly a dozen times; Timothy Munroe ran for his life and escaped, despite a bullet in the leg and buttons on his waistcoat shot away. Eight militiamen who barricaded themselves in the cellar survived after shooting a regular who ventured down the stairs, but others upstairs were killed, perhaps executed. A dozen bodies later were laid side by side in the south room, their blood soaking the plank floor.