Полная версия

The British Are Coming

Life in besieged Boston grew grimmer by the day. Soon after the fighting began, General Gage agreed to issue exit permits to those who wanted to leave town if all citizens surrendered their weapons at Faneuil Hall. By late April, some 1,778 firelocks had been handed over, plus 634 pistols, 973 bayonets, and 38 ancient blunderbusses. Gage insisted that swords also be added to the pile. “Nearly half the inhabitants have left the town already,” the merchant John Andrews wrote a friend on May 6. “You see parents that are lucky enough to procure papers, with bundles in one hand and a string of children in the other, wandering out of town … not knowing where they’ll go.” Provisions grew short, prices soared, fresh food vanished. “Pork and beans one day,” Andrews wrote, “and beans and pork another.”

Loyalists from the countryside slipped into Boston for Crown protection, then complained bitterly to Gage that allowing all rebel sympathizers to leave would invite bombardment of the town; hostages must be kept to discourage attack. Gage saw the point, and the exodus largely stopped except for those able to sneak out by boat. “It is inconceivable the distress and ruin this unnatural dispute has caused to this town and its inhabitants,” the surveyor Henry Pelham wrote on May 16. “Almost every shop and store is shut. No business of any kind is going on.” A British lieutenant observed after taking a stroll, “I can’t help looking on it as a ruined town. I think I see the grass growing in every street.” More grass was needed: provender for British horses by late May was short by three thousand tons. Warming weather and a diet of salt meat brought widespread illness. Reverend Henry Caner, a loyalist, would write to London, “It is not uncommon to bury 20 to 30 a week among the troops and inhabitants.… If our lives must pay for our loyalty, God’s will be done.” Another loyalist clergyman, Reverend John Wiswall, who took refuge with his family in Boston from Cape Cod, noted in his journal, “My daughter died the 23rd and my wife the 26th. Buried in family tomb the 28th.”

From his Province House headquarters, Gage awaited reinforcements and braced against a rebel assault. Regiments built several small batteries on the Common and a larger redoubt on Beacon Hill. Gunners at Boston Neck were ordered to keep lighted matches by their cannons at all times. Regulars patrolled the wharves every half hour. Loyalist volunteers with white cockades in their hats kept vigil in the streets at night. “We are threatened with great multitudes,” Gage wrote Lord Dartmouth in mid-May. “The people called friends of government are few.” News from the other provinces was bleak. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire were “in open rebellion,” he told London. “They are arming at New York and, as we are told, in Philadelphia and all the southern provinces.” The royal mail was no longer secure; a postal rider with official correspondence from New York had been detained, his locked bag jimmied open with hammer and pliers.

Guard boat crews patrolled the harbor with 6-pounders, alert for fire rafts and often ducking sniper rounds from the far shore. Ships from England no sooner dropped anchor than potshots rang out. “The country is all in arms, and we are absolutely invested with many thousand men, some of them so daring as to come very near our outposts,” Captain Glanville Evelyn wrote his father in Scotland. Morale sank in the regular ranks. A Royal Navy surgeon permitted to treat wounded British captives in Cambridge wrote in May that the rebel army “is truly nothing but a drunken, canting, lying, praying, hypocritical rabble, without order, subjection, discipline, or cleanliness.” A new British drinking song warned:

Boston we shall in ashes lay,

It is a nest of knaves,

We’ll make them soon for mercy pray,

Or send them to their graves.

There would be ashes on May 17. That night, a sergeant in the 65th Regiment reportedly delivered musket cartridges by candlelight to the barracks on Treat’s Wharf; soon after his arrival, a small, accidental blaze grew into a conflagration that burned until three a.m. Gage had placed the town’s fire engines under military control, and inept redcoats, one merchant complained, operated the apparatus “with such stupidity that the flames raged with incredible fury & destroyed 30 stores.” The losses at Dock Square also included regimental uniforms, weapons, and donations collected for Boston’s poor.

Fresh meat for British larders and forage for British horses could be found within a mile or two of Province House, but trouble could be found there as well. In Boston Harbor, more than thirty islands—used for over a century as livestock pastures and hay fields—stippled the narrow, twisting approaches from open water. Shoals, mudflats, salt creeks, and sandbars changed shape with each new tide. Much of the harbor at low water was no deeper than three fathoms—eighteen feet—while the three largest Royal Navy ships on station drew twenty feet or more. American mariners skittered through this watery terrain in smacks, canoes, and whaleboats, trading shots at long range with British foraging parties. On May 21, Gage sent several sloops to Grape Island, but they scavenged only eight tons of hay before rebels burned eighty more.

On Saturday morning, May 27, six hundred Massachusetts and New Hampshire militiamen scuffed from the Chelsea meetinghouse down Beach Road to the shoreline. By eleven a.m., the ebbing tide had fallen enough to let them slosh knee-deep across narrow Belle Isle Creek to Hog Island, where, as ordered by the Committee of Safety, they rounded up 411 sheep, 27 cows, and 6 horses, shooting those that would not be herded. The British were to get none. Thirty men waded across Crooked Creek to adjacent Noddle’s Island, at the confluence of the Charles and Mystic Rivers. At seven hundred acres, Noddle’s was the largest of the harbor isles, once a refuge for Baptist apostates driven from Boston by Puritans, and long a favorite dueling ground for aggrieved parties of all denominations. Here the rebels set fire to a barn piled high with salt hay.

Aboard the fifty-gun Preston in the Boston anchorage, the sight of thick smoke to the east caught the squinting eye of Samuel Graves, commander of the North American station. Graves this very week had received news from London of his promotion to vice admiral of the white; he celebrated with a thirteen-gun salute from his squadron and colors appropriate to his new rank hoisted above Preston’s deck. A sixty-two-year-old sea dog who had never held high command before arriving in America a year earlier, Graves was a harbor admiral; recovering from a small stroke, he had shuttled between his flagship and a comfortable house on Pearl Street without once in nineteen months venturing out past the Boston lighthouse. His talents were modest—the new promotion notwithstanding—and his grievances many. With thirty vessels in his squadron, but only four substantial ships of force, he was to ensure that Britannia ruled the waves along an eighteen-hundred-mile littoral, from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Cape Florida. Despite a stupendous increase in smuggling by American insurgents, he admitted that during this past winter “no seizures of any consequence have been made.”

Graves badgered the Admiralty with legitimate complaints about “properly guarding this extensive coast with the few vessels I have”; about the poor condition of those vessels—Hope was “very leaky,” and so were Halifax, Somerset, and others; about the difficulty of getting guns, pilots, provisions, and proper sailors; and about idiotic orders from home, including a directive to search the ballast of every ship arriving in North America for smuggled musket flints, as if ample flint could not be found in American rock. He also complained about General Gage, whom he detested and who detested him in return. With four nephews at sea in the king’s service, Graves was a master of nepotism; Lord North’s undersecretary, William Eden, would describe him this year as “a corrupt admiral without any shadow of capacity.” He was suspected, among other indiscretions, of selling stringy mutton on the Boston black market. Captain Evelyn spoke for many in asserting that “every man both in the army and navy wishes him recalled.”

Graves loathed “rebellious fanatics,” and in that smoke billowing from Noddle’s Island he spied a chance to show General Gage how they should be fought. At three p.m., a detachment of 170 marines from Glasgow, Cerberus, and Somerset landed on the island’s western flank. At the same time, the Diana, a new 120-ton armed schooner just that morning back from chasing gunrunners in Maine under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Graves—from the quartet of nephews—worked her way into Chelsea Creek, which separated the mainland from Noddle’s and Hog Islands. More marines followed Diana in a dozen longboats to cut off the rebel retreat. The pop of militia muskets now sounded from behind stone walls around the Winnisimet ferry landing. Diana answered with grapeshot and bore down on rebel drovers herding livestock through the shallows and onto Beach Road. Fifteen militiamen squatted in a Noddle’s marsh as a rear guard, swapping volleys with the regulars. “The bullets flew very thick,” Corporal Amos Farnsworth of Groton reported. “The balls sung like bees round our heads.” From the Cerberus quarterdeck, marines manhandled a pair of 3-pounders ashore and from a sandy embankment shelled the ferry landing.

Spattered with fire from both flanks, Lieutenant Graves decided that Diana had gone far enough. But as he sought to come about, the wind died. Longboats nosed alongside with hawsers to tow her down Chelsea Creek. Bullets smacked the water. Oarsmen bent low at the gunwales as the schooner inched back toward the wider harbor.

At twilight three hundred militia reinforcements rushed into the skirmish line with their own pair of 3-pounders, the first use of American field artillery in the war. In command was a stubby, rough-hewn brawler with a shock of white hair. Brigadier General Israel Putnam—“Old Put” to his men—was described by the Middlesex Journal as “very strongly made, no fat, all bones and muscles; he has a lisp in his speech and is now upwards of sixty years of age.” A wool merchant and farmer from Connecticut, barely literate, Putnam “dared to lead where any dared to follow,” one admirer observed; another called him “totally unfit for everything but fighting.” Stories had been told of him for decades in New England, most involving peril and great courage: how he once tracked down a wolf preying on his sheep, crawled headfirst into its den with a birch-bark torch to shoot it, then dragged the carcass out by the ears; how in the French war when a fire ignited a barracks, he organized a bucket brigade to save three hundred barrels of gunpowder, tossing pails of water onto the burning rafters from a ladder while wearing soaked mittens cut from a blanket; how he had been captured, starved, and tortured by Iroquois in 1758, and only the timely intervention of a French officer kept him from burning at the stake; how, after being shipwrecked on the Cuban coast during the Anglo-American expedition against Havana in 1762, he saved all hands by building rafts from spars and planks; how he had fought rebellious Indians near Detroit in Pontiac’s War of 1764, and later explored the Mississippi River valley; how he had left his plow upon hearing news of Lexington to ride a hundred miles in twenty-four hours to Cambridge. Now, wearing his scars and scorches like valor ribbons, he was ready to destroy Diana.

She was poised for destruction. After finally coming abreast of Winnisimet ferry just after ten p.m., the schooner was caught in a falling tide, her hull scraping bottom. The rebel fusillade from shore intensified, the gunners firing blindly at shadows on a moonless night, but vicious enough to kill two sailors, wound others, and cause the longboats to cast off their tow ropes. Lieutenant Graves tried to rig a kedge anchor and windlass to haul Diana free, but she stuck fast sixty yards from the beach, then heeled over onto her beam ends. The armed sloop Britannia eased close to pluck the crew from the canted deck as rebel 3-pounders boomed and Putnam, said to be wading waist-deep across the mudflats, shouted insults and blandishments in the dark. Swarming militiamen stripped the schooner of cannons, a dozen swivel guns, rigging, and sails, then piled hay under her bow and set it ablaze. At three a.m. flames reached the magazine, and Diana exploded in a fine rain of splintered oak.

Admiral of the White Graves buried his dead and ordered Somerset at dawn to fire long-range on the jubilant crowd capering along the Chelsea shore. Gage was disgusted by the schooner’s loss. “The general,” an aide wrote, “by no means approved of the admiral’s scheme, supposed it to be a trap, which it proved to be.” American raiders would return to the islands over the next two weeks, rustling another two thousand head of livestock while burning corn cribs, barns, and—heaping insult on the injuries—a storehouse that Graves had rented for cordage, lumber, and barrel staves.

“Heaven apparently and most evidently fights for us,” one Jonathan exulted. Putnam and his men returned to Cambridge in high feather. Diana’s mast had been salvaged and soon stood as a seventy-six-foot flagpole on Prospect Hill. A captured British barge with the sail hoisted was placed in a wagon and paraded around the Roxbury meetinghouse in early June to cheers and cannon salutes. “I wish,” Putnam was quoted as saying, “we have something of this kind to do every day.”

Gage declared martial law on June 12 with a long, windy denunciation of “the infatuated multitudes.” He offered to pardon those who “lay down their arms and return to the duties of peaceable subjects,” exclusive of Samuel Adams and John Hancock, “whose offenses are of too flagitious a nature” to forgive. He ended the screed with “God save the King.”

The same day, Gage wrote to Lord Barrington, the secretary at war, that “things are now come to that crisis that we must avail ourselves of every resource, even to raise the Negroes in our cause.… Hanoverians, Hessians, perhaps Russians may be hired.” To Lord Dartmouth he warned that he was critically low on both cash—he could not pay his officers—and forage; ships had been sent to Nova Scotia and Quebec seeking hay and oats. Crushing the rebellion, he estimated, would require more frigates and at least 32,000 soldiers, including 10,000 in New York, 7,000 around Lake Champlain, and 15,000 in New England. Another officer writing from Boston on June 12 advised London—the king himself received a copy—that the rebel blockade “is judicious & strong.” As for British operations, “all warlike preparations are wanting. No survey of the adjacent country, no proper boats for landing troops, not a sufficient number of horses for the artillery nor for the regimental baggage.” The war chest had “about three or four thousand [pounds] only remaining.… The rebellious colonies will supply nothing.”

Gage’s adjutant complained that “every idle report is carried to headquarters and … magnified to such a degree that rebels are seen in the air carrying cannon and mortars on their shoulders.” Some regulars longed for a decisive battle; “taking the bull by the horns” became an oft-heard phrase in the regiments. “I wish the Americans may be brought to a sense of their duty,” an officer wrote in mid-June. “One good drubbing, which I long to give them … might have a good effect.” As Captain Evelyn told his cousin in London, “If there is an honor in hard knocks, we are likely to have some share.”

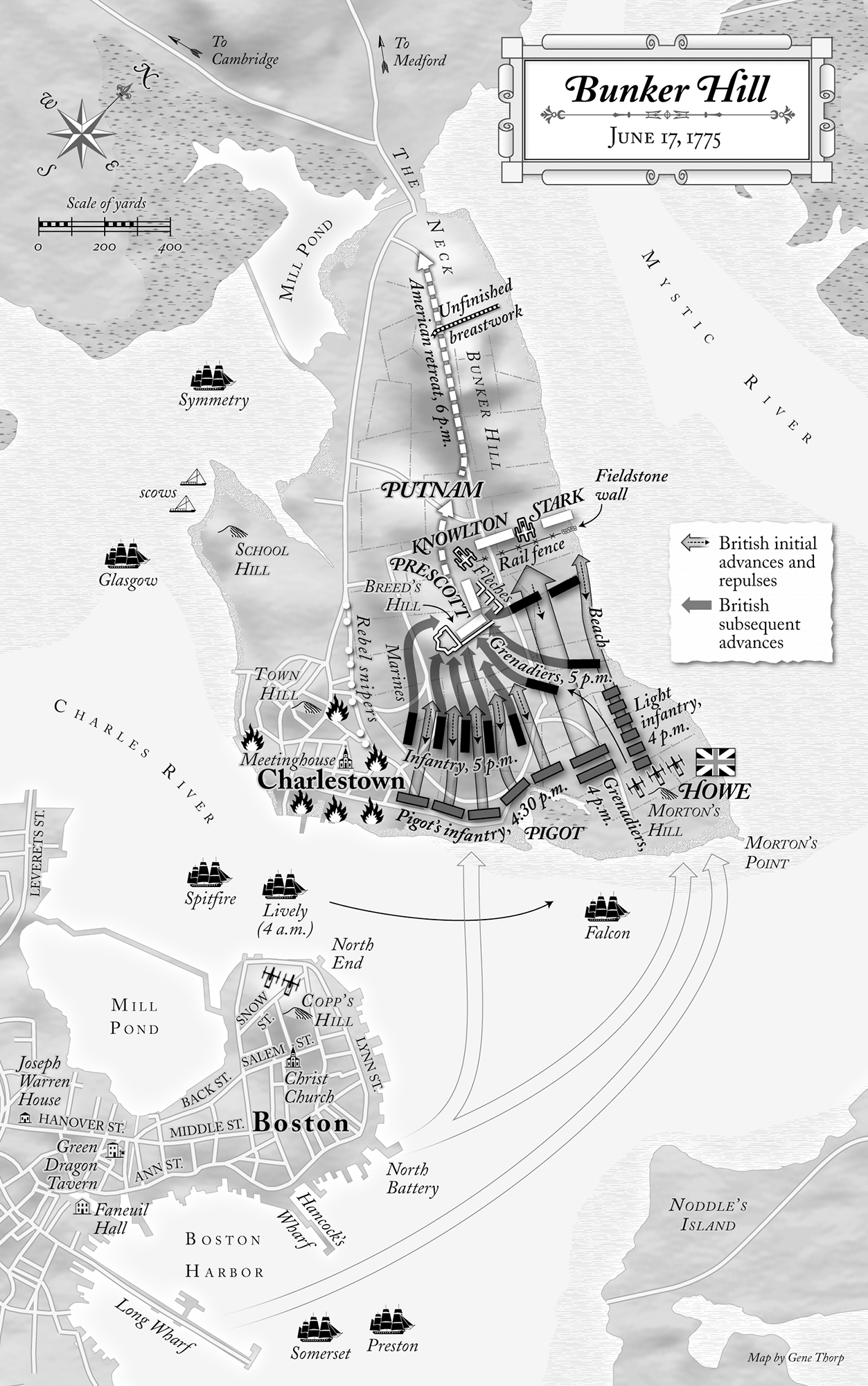

The imminent arrival of transports with light dragoons, more marines, and several foot regiments would bring the British garrison to over six thousand troops, not enough to subdue Massachusetts, much less the continent, but sufficient, as Gage told London, to “make an attempt upon some of the rebel posts, which becomes every day more necessary.” Two alluring patches of high ground remained unfortified, and Gage knew from an informant that American commanders coveted the same slopes: the elevation beyond Boston Neck known as the Dorchester Heights, and the dominant terrain above Charlestown called Bunker, or Bunker’s Hill. A battle plan was made to seize the former on Sunday, June 18, with a bombardment of Roxbury while the rebels were at church, followed by the construction of two artillery redoubts on the heights. If all went well, regulars could then capture the high ground on Charlestown peninsula and eventually attack the American encampment at Cambridge.

No sooner was the plan conceived than it leaked to the Committee of Safety; British officers seemed incapable of keeping their mouths shut in a town full of American spies and eavesdroppers. Intelligence even came from New Hampshire, where a traveler out of Boston told authorities there about rumors of an imminent British sally. Meeting in Hastings House, a gambrel-roofed mansion near the Cambridge Common, the committee on June 15 voted unanimously that “the hill called Bunker’s Hill in Charlestown be securely kept and defended.” Dorchester Heights would have to wait until more guns and powder could be stockpiled.

The American camps bustled. Arms and ammunition were inspected, with each marching soldier to carry thirty rounds. A note to the Committee of Supply advised that “the army is destitute of shirts & trousers, and if any [are] in store, pray they may be sent.” Liquor sales stopped, again. Teamsters carted the books and scientific instruments from Harvard’s library to Andover for safekeeping. Organ pipes were yanked from the Anglican church and melted down for musket bullets. An ordnance storehouse issued all forty-eight shovels in stock as well as ammunition to selected regiments—typically forty or fifty pounds of powder, a thousand balls, and a few hundred flints. Commissaries in Cambridge and Roxbury reported that provisions arriving through June 16 included 1,869 loaves of bread and 357 gallons of milk from Cambridge vendors, 60 pairs of shoes from Milton, 1,570 pounds of beef and 40 barrels of beer from Watertown, a ton of candles, 1,500 pounds of soap, several hundred barrels of beans, peas, flour, and salt fish by the quintal, rum by the hogshead, and a few hundred tents, many without poles. All Massachusetts men within twenty miles of the coast were urged to carry their firelocks “to meeting on the Sabbath and other days when they meet for public worship.” A sergeant from Wethersfield wrote his wife, “We’ve been in a great deal of hubbub.”

Orders spilled from the headquarters of Major General Ward, who occupied a southeast room on the Hastings House ground floor. Portly and sallow, sporting a powdered wig, boots, and a long coat with silver buttons, Artemas Ward, now forty-seven, had been chosen in February to command the Massachusetts militia on the strength of his long tenure in colonial politics. As a Harvard student, he once helped lead a campaign against “swearing and cursing” at the college; as a justice of the peace in Shrewsbury, he’d levied fines against the profane and could be found in the street reprimanding those who dishonored the Sabbath with unnecessary travel. Massachusetts, he believed, was home to the Chosen People. Ward had never fully recovered his health after the rigors of the French war, from which he’d emerged as a militia lieutenant colonel despite seeing little action. “Attacks of the stone”—kidney stones—still tormented him. Pious, honest, and devoted to the patriot cause, he was also taciturn, torpid, and stubborn. The gambit to hold Bunker Hill in Charlestown that he and the Committee of Safety had concocted was an impulse, not a plan. The rebel force lacked not only sufficient ammunition and field artillery but also combat reserves, a coherent chain of command, and even water. Ward had recently requested from the provincial congress almost sixty guns, fifteen hundred muskets, twenty tons of powder, and a similar quantity of lead; few of those munitions had been forthcoming.

Shortly after six p.m. on Friday, June 16, three Massachusetts regiments drifted through the arching elms and onto the Cambridge Common. They wore the usual homespun linen shirts and breeches tinted with walnut or sumac dye. Most carried a blanket or bedroll, often with a tumpline strap across the forehead to support the weight on their backs. A clergyman’s benediction droned over their bowed heads, and with a final amen they replaced their low-crowned hats and turned east down the Charlestown road.

Twilight faded and was gone, and the last birdsong faded with it. The first stars threw down their silver spears. Little rain had fallen in the past month, and dust boiled beneath each step. Candlelight gleamed from the rear of two bull’s-eye lanterns carried by sergeants at the head of the column. Officers commanded silence, and only the rattle of carts stacked with entrenching tools broke the quiet. Through parched orchards and across Willis Creek they marched, and past the hulking shadows of Prospect and Winter Hills. As they turned right toward Charlestown, a couple hundred Connecticut troops joined the column, bringing their strength to a thousand men.

General Ward had remained in his Hastings House headquarters, and the column was led by a sinewy, azure-eyed colonel wearing a blue coat with a single row of buttons and a tricorne hat. He carried a linen banyan. William Prescott of Pepperell, forty-nine and bookish, had fought twice in Canada during wars against the French, earning a reputation for cool self-possession under fire. In this war he reportedly had vowed never to be taken alive. “He was a bold man,” one soldier later wrote of him, “and gave his orders like a bold man.”

Bold orders this evening would prove to be ill-considered. As the procession crossed Charlestown Neck—barely ten yards wide at high tide—Prescott briefly conferred with the irrepressible Israel Putnam and Colonel Richard Gridley, an artilleryman and engineer who had also fought twice in Canada with distinction. From just below the isthmus, the three officers contemplated the dark contours of Charlestown peninsula, an irregular triangle a mile long and less than half that in width, bracketed by the Mystic and Charles Rivers. Even at night the dominant terrain was obvious: Bunker Hill rose gradually from the Neck for three hundred yards to a rounded crown 110 feet high, commanding not only the single land route off the peninsula, but the approach roads from Cambridge and Medford, as well as the adjacent waters. From the crest a low ridge swept southeast another six hundred yards to the patchwork of pastures, seventy-five feet high and sutured with rail fences, that would be called Breed’s Hill. Some fields had been scythed, the grass laid in windrows and cocks; in others it still stood waist-high. Brick kilns and clay pits pocked the steep eastern slope of the Breed’s pastures. Gardens and small orchards lay scattered to the west, backing the four hundred houses, shops, and buildings in Charlestown. Most of the three thousand residents had fled inland. The rising moon, three days past full, laved the town in amber light. Beyond the ferry landing and a spiny-masted warship in the Charles lay slumbering Boston.

For reasons never explained and certainly never understood, when the conference ended Prescott ordered the column to continue southeast. Colonel Gridley quickly staked out a redoubt—an imperfect square with sides about 130 feet long—not on nearly impregnable Bunker Hill, as the Committee of Safety had specified, but on the southwest slope of Breed’s pastureland. Accustomed to pick-and-shovel work, the men grabbed tools from the carts and began hacking at the hillside. Striking clocks in Boston, echoed at higher pitch by a ship’s bell, told them it was midnight.

The rhythmic chink of metal on hard ground carried to the Lively, another of those leaky vessels in the British squadron, now anchored astride the Charlestown ferryway. As coral light seeped across the eastern horizon at four a.m. on Saturday, June 17, the graveyard watch officer strained to decipher the odd sounds above the groan of the ship’s yards and the Charles whispering along her hull. He summoned the captain, whose spyglass soon showed hundreds of tiny dark figures tearing at the distant slope with spade and mattock.