полная версия

полная версияArmenophobia in Azerbaijan

The most favored practice of Azerbaijani authors was renaming medieval Armenian political figures, historians and writers who lived and worked in Karabakh turning them into Albanians. In this way, Movses Kaghankatvatsi who had written in the Armenian language metamorphosed into the Albanian historian Moisey Kalankatuyski. The same lot was reserved for the Armenian prince Sahly ibn-Sumbat (Armenians preferred to call him Sahl Smbatyan) who underwent a transmutation becoming half-Albanian, half-Azerbaijani.88

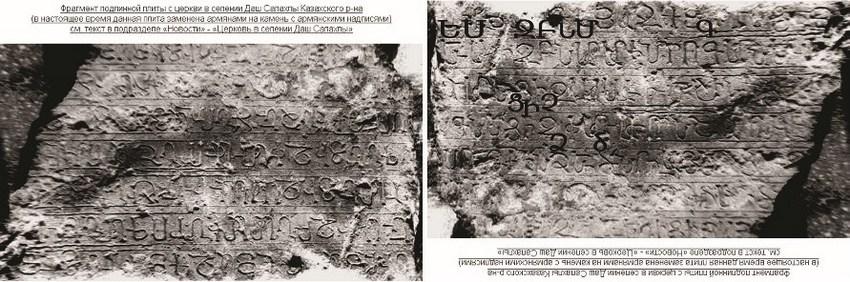

The academician Farida Mamedova who is a fiery preacher of the myth on Albanian (that is Azerbaijani) origin of Karabakh abuses the fact that the Azerbaijani readership does not know Armenian to deliberately mislead it. Thus, in her book entitled The History of Caucasian Albania, as evidence of “Armenian falsifications” she publishes a photograph of a stone slab carrying an inscription in Armenian which is rotated at 180 degrees89 and tagged as a “fragment of a genuine (Albanian) slab from the church in the village of Dash Salakhli of Qazakh region”90. The inscription is so crisp that any person familiar with Armenian and Armenian script can read it without any special training.

Without dwelling on numerous scholarly self-contradictions,91 we must only underscore that using her feigned knowledge of the Armenian language and misleading her readership is the keynote of her entire scientific activity and scholarly works. In this way, in an attempt to prove the Albanian origins of Gandzasar Monastery92 located in Nagorno-Karabakh, she resorts to the same trick used earlier and passes the Armenian language for Albanian:

I saw the inscription in Gandzasar in 1978 when I was there along with Azerbaijani scientists accompanied by Armenians of Karabakh for this very purpose. On my way there I already knew of the existence of this inscription in the Gandzasar monastery made at the behest of Hassan Jalal which reads specifically as follows: “… I built this cathedral for my Albanian people” (in Albanian: – imaguvaniazgn).93

The scholar that claims knowledge of the Armenian and ‘Albanian’ languages affirms that imaguvaniazg is an Albanian word while, actually, it contains three Armenian words: ‘im’ – my (իմ), ‘aguanits’ from Aghvan (Աղվանից) and ‘azg’ clan (ազգ) merged into a single word ‘in Albanian language’, and with the same meaning for that matter. But the most interesting thing is that no such inscription has ever existed in Gandzasar.94 This is a blatant example of an egregious falsification of the modern times.

The school curriculum was purged from Armenian authors (this particularly refers to the works of the first people’s writer of Azerbaijan, Alexander Shirvanzadeh95). The literary works by Azerbaijani authors of the turn of the 19th century viewed as classics of Azerbaijani literature which portrayed Armenians in the positive light and contained appeals for brotherhood and peace (works of Sabir, Hajibekov96, and Mirza Jalil97) were expunged.

Enlightenment advocates of the early 20th century were replaced by the partisans of ideology and propaganda that appealed to a national unity balked by Armenians.

“Glory to the heroes of Sumgait” was the slogan of the public rallies bringing together thousands of people in the city of Baku.

Bakhtiyar Vahabzadeh, people’s writer of Azerbaijan: The time will come when we will realize the courage and heroic deeds of plain Azerbaijani guys in Sumgait who started the purge of our country from the Armenian filth.98

In his book entitled Polygon of Azerbaijan, Aris Kazinyan notes an essential role of rumors as a main propaganda weapon of all times in shaping the behavior of ignorant popular masses.99

It is very illustrative that at the beginning of the past century many journalists, missionaries and diplomats who worked either in the Ottoman Empire or in the Transcaucasia noted that the very fact of rumors about violent acts against Muslims at the hands of Armenian was the symptom of a forthcoming massacre, an anticipation of new Armenian pogroms. There is an amazing continuity not only in the rites of violence, but also in the pretexts for perpetrating it. On the eve of every Armenian massacre Ottomans and Turkish Tatars spread false rumors about carnage of Muslim populations at the hands of ‘gyavurs’ in some remote areas, about Armenian plans to attack Turkish districts in specific cities. <…> In 1905, the newspaper Tiflis Leaflet (Тифлиский Листок) published a report on the situation in the Eastern Caucasia: “In the mid-August, the provinces of Aresh, Jevanshir and other places were upset by a gruesome rumor: it was claimed that Armenians attacked peaceful nomads near the village of Vank and massacred many women and children. Three hundred armed horsemen from Aghdam moved into the area only to find out that there had been a skirmish about seven stolen sheep, with two Tatars killed and several Armenians wounded. Such conflicts happened every year and involved more severe bloodshed. But the formal pretext was found (Tiflis Leaflet, 21.08.1905)100.

On the eve of the Sumgait massacre, the same traditional scenario came into play: certain individuals appeared in Baku, Sumgait and other regions of Azerbaijan telling the stories of Azerbaijani pogroms in Kapan (Kafan) region of Armenia and displaced compatriots.

A similar scenario was staged in January 1990 during the massacre of Armenians in Baku. An eyewitness of these events, the Colonel V. Anokhin reported: “I am sure that the more fantastic the lie is, the higher are the odds that people will be taken in. The deception techniques are sometimes monstrous. For instance, a public rally is held in the neighboring district to commemorate 1000 dead in Kurdamir. When I tell the residents of Kurdamir about it, they are astounded; they surely know that there is not a single loss of life there. However, they themselves go around telling stories of forty thousand Azerbaijanis killed in Baku”.101

As a result, all things that caused the alarm and concern of Azerbaijani thinkers again led to the frustration of Azerbaijani intellectuals rather than consolidated it.

Mirmehdi Agaoghlu, writer: My views of Armenians were shaped amid the famous slogan: “He, who does not sit, is Armenian”. The events on the central square began with millions of people squatting and standing up following this command. Just like the grown-ups, we, the kids, had a slogan of our own: “Wherever you see Armenian, hit him on the head with a pail”. We had but one enemy: the Armenian enemy. We heard this propaganda from the Azerbaijani television, we were taught this at school. The Armenian ‘dyga’102 were our enemies. We grew up amid this hatred towards Armenians. The state machinery of propaganda portrayed Armenians as a fictitious people that never had statehood, parasites and cheap prostitutes who lived off other countries. <…> Do you want to know the truth? In the past 20–25 years, your own historians and authors of propaganda told you lies. On the top of it, Armenian sources also indulge in exaggeration. Now try to distinguish fiction from reality. Every time I saw Armenian actors, scientists or representatives of other spheres of life on Russian channels, I felt resentment but still asked myself the question: If they are indeed such a tiny little nation that we can easily be done with, why do we come across them everywhere? Why are we not like them?

So, gradually the hatred inside me transformed into a complex of inferiority. And I felt angry because I had been deceived all this time.103

Journalist Farheddin Hajibeyli: Why do we always suffer a defeat? There is no one to blame except us, boycott YOURSELVES!

Nobody is head over ears in love with black eyebrows and eyes of Armenians. They accomplished what they have today after decades of hard work. Let us consider them our enemies cursing and abusing them, but for the sake of justice we must recognize their right to all these victories, as they have been accomplished due to their intellect and foresight. <…> Now, let us be honest: who is more worthy of victories? Us or them?104

After the country’s independence, the Azerbaijani quest for national identity and consolidation through inculcation and cultivation of the image of the external Armenian enemy by manipulating the public mind was given free rein through self-expression.

3. Armenians in Baku

One of the main propaganda tricks employed by the official Baku in disseminating the myth of its tolerance and commitment to multiculturalism – the one that becomes a fertile ground for cultivation and indoctrination of armenophobia – rests upon the assumption that 30 thousand Armenians live in Azerbaijan.

This myth of 30 thousands Armenians in Baku is quite actively exploited by the Azerbaijani propaganda. The late national leader Heydar Aliyev was the first to come up with this statement.105 Later, this figure fluctuated depending on the situation at hand and the needs of the day. For example, in 2008 Ziyafat Asgarov, the vice-speaker of the parliament stated: “Presently, there are approximately 50,000 Armenians living in Azerbaijan, and they face no problems”.106 In his turn, Araz Alizadeh, the chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Azerbaijan, curtails the number of Armenians by 10 thousands and brings up a figure of 40,000 Armenians living in the country.107 In the meantime, Elnur Aslanov, the head of the Division of Political Analysis and Information Support of the President’s Administration of Azerbaijan speaks about some 20,000 Armenians.108 Ganira Pashayeva, member of the Azerbaijani parliament, confined herself to invoking “thousands of Armenians” without specifying their precise number.109

Meantime, according to the official census of 1999, there were about 645 Armenians living on the territories controlled by Azerbaijan,110 while the census of 2009 placed the number of Armenians at 193.111 In this reference, the Azerbaijani side brandishes the argument that the Armenians who live in Azerbaijan do so in a stateless capacity and, therefore, are not covered in the census.

It must be noted that this refusal to issue documents on the ground of ethnicity,112 which dates back some 20 years, is in itself indicative of an ongoing apartheid and segregation policy against Armenians.

In the study Ethnicity as a social status and stigma: Armenians in the post-soviet Azerbaijan, published by Heinrich Böll Foundation,113 Sevil Huseinova notes that after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, ethnic Armenians who had lived in Baku were stripped of their status of equal members of the local urban community. This was determined not only by ethnic demarcation of the population. Their status of equal community members was lost during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, as Armenian ethnicity virtually became synonymous with the concepts of enemy and alien. This occurred as the ongoing conflict came to stigmatize the ethnic identity of Armenians. Being Armenian and living in Azerbaijan represented a contradiction and no longer met the standard of a ‘good citizen’. The self-perception of Armenians living in Baku crystallized in this context.

In addition, the ideology stating that the stigmatized Armenian residents of Baku constitute a threat or provoke negative emotions permeates the information space of Baku and Azerbaijan, as a whole. The borderline between stigmatized and correct persons is clearly marked. “The media and the daily life swarm with concepts of stigma: “historical enemies”, “a small Armenian bastard”, the derogatory term “Khachik” and so forth. You can say that ethnicity becomes the quality which sets apart the Armenians of Baku and distinguishes them from the other residents of the city and other citizens of Azerbaijan”.114

Following a spate of pogroms on the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan and attempts to completely purge the country of ethnic Armenians, some of them had to remain in Azerbaijan for various reasons.

They can be conventionally divided into several categories since they often migrate from one category into another.

1. Elderly, sick and lonely people are those who were not in position to leave the country and did not envisage their lives elsewhere, as Azerbaijan was the place where they had been born and raised; they had no other place to go and no one to host them.

There are no data on the number and later fates of those who had been stranded on the territory of Azerbaijan. However, it can be reasonably assumed that by now most of them have already passed away due to their health condition, age and lack of proper care and social protection.

2. Persons bound by intermarriage: those included under this category can be ranked as the most ‘problem-free’ as they enjoy protection from their husbands and children. As Sevil Huseinova notes in her research,115 these were Armenian women who had married the Azerbaijanis, and whose husbands and children could warrant their safety. As a rule, their lives were less endangered during the pogroms, their houses were not seized, and many of them could keep their jobs and property.

However, as evidenced by scarce publications and reports by international organizations, these women, too, had to face manifestations of extreme, moderate or latent xenophobia. For personal safety reasons, they had to alter their appearance116, last and first names, place of residence and work; they also concealed their origin to fully accommodate the realities of the modern Azerbaijan, but on the whole they had no regrets about the choice they made.

Liana – Leila: “By then, I had already formally changed my name to Leïla. But shortly after, our new neighbors, who were Azerbaijanis banished from Armenia, learned about my Armenian descent. At first, they shot angry glances at me. When they saw me passing in the street, they used to hurl abuse at my back so that I could hear it. Their resentment was understandable as they had lost their homes and shelter, just like the Armenians, who had been forced to leave the city, in which they had lived for decades. I understood why they did not treat me well. But this lasted only a short time. Time heals all, as I learned first-hand. Our neighbors accepted me, and we have had very good relations,” tells Leïla. < > Nobody in Lankaran, except her husband’s family, knows of Leïla’s Armenian descent.117

However, this relatively unscathed category of women includes those who found themselves marooned in the Azerbaijani society and had to go through their share of trials and tribulations reserved for Armenians. Manush Khujoyan, the representative of the Saved Relics organization, told the story of the sister of one of their organization members who had remained in Baku.

“During the Sumgait pogroms, as everybody was fleeing, the husband of that woman had convinced her to stay behind, vouching for her safety; however, with the advent of the Karabakh war, he immediately divorced her. This woman shares the lot of many other Armenians in Azerbaijan and lives in very poor conditions, without any documents. To this day, she holds a soviet passport”. The ‘Saved Relics’ wanted to help this woman come to Armenia with the mediation of the Red Cross; however, she refused to contact the Red Cross as she seriously feared for her life.118

3. The term Homo soveticus refers to those who had hoped that the “tide” would subside, and the things would resume their ordinary course. Account must be taken of the fact, that the pogroms were perpetrated as the Soviet Union was still alive and kicking, and it could not possibly occur to a number of people that the soviet government would not find a way to remedy the situation. A year later, as the Soviet Union disintegrated, the ensuing economic collapse and the war against Nagorno-Karabakh Republic made travel impossible as crossing the border meant disclosing one’s ethnic origin and therefore was unsafe.

Kamalya Yesina, Karina Sargsyan: She wanted to leave, but stayed. At first, she thought that things would get to normal, and it was only a nightmare. But with every new day, the situation spiraled. Neighbors and relatives left the country. Memories of past conversations rushed back. “Didn’t I foretell this situation,” said her uncle in one of those ‘kitchen conversations’, and he was right. <…> The decade of the 1980s drew to its end… Sitting in an empty kitchen, she answered the questions of her own monologue. And they were so numerous. There could be but one answer: pack up things and leave. But where and why? <…> “Good that my parents didn’t live to see these dreadful days. At the turn of the 1990s, the neighbors left. For good. Tears poured profusely. Hopelessness, fear and bitterness”, recalls Karina. Her relatives who lived next door left back in January 1990. <…> As they left, she knew for sure that she would stay in Baku. <…> Her last name is Russian, her children are considered Russians, and Russians are spared in Azerbaijan,” and they will spare me too,” she reasoned. <…> Today, Kamalya Yesina has no regrets about her staying. She simply could not leave. But she confides that these years have claimed a heavy toll on her looks… prematurely.119

Zhanna Shahmuradyan: Baku. Two women of Armenian descent will receive identity documents from the Republic of Azerbaijan. <…> Earlier the applicant Zh. Shahmuradyan filed a court petition asking to issue an identity document for her daughter. The applicant motivated her claim with the fact that she was born in Baku in 1966 and had lived there ever since. In 1983, she was issued a soviet passport for the last time. She never left the territory of Azerbaijan, but the police turned down her request for evident reasons. In 1992, she met an Azerbaijani man and lived with him for a while in a common-law marriage. They had a daughter named Ayla. However, as the girl’s mother had no documents, the child was not issued a birth certificate. In the meanwhile, Zh. Shahmuradyan submitted evidence to the Administrative-Economic Court № 1 of Baku attesting the fact that she and her daughter indeed had lived in Azerbaijan for many years. As a result, the court instructed the Main Passport, Registration and Migration Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs to issue documents to these women. “After we receive the documents, I will first of all travel to Russia to meet my mother whom I haven’t seen for long. But I will have to return to my daughter”, says the woman.120

Nora Vartanesovna Varagyan: After the ruling of the Court of Appeals of Baku in respect of the Police Department of Nasimi district, the applicant Nora Vartanesovna Varagyan filed a cassation appeal to the Supreme Court. Presently, the case is examined by Asad Mirzoyev, Civil Board member of the Supreme Court. The cassation will be examined on May 8.

It must be noted that in 1991, in the first years of the armed aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan, Nora Vartanesovna Varagyan left the place of her residential registration121 in Nasimi district. Subsequently, she was not registered at any other domicile. In 2007, she filed an application with the Passport Office of the Police Department of Nasimi district to receive an identity document. But the Passport Office of the Police Department of Nasimi district turned down her application since her registration as resident had been ended, after which N. Varagyan filed a complaint in the local court against the actions of the official of the Police Department of Nasimi district. The Nasimi District Court and the Baku Court of Appeals ruled to deny her claim.122

4. Persons completely integrated into the Azerbaijani society and not wishing to live elsewhere. They are linked to the Armenian ethnicity in name only, but not in self-awareness. An example: The father of Elvira Movsesyan who doomed his family and children to decades of trials and tribulations, or Anzhela Oganova.

Anzhela Oganova: “I love my city so much. Not for a second did I want to leave the place,” said Anzhela Oganova as we met. <…> In 1992, she was forced to quit her job. <…> “She came running to the Office of the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly and voiced her complaint: she was tormented and battered by her neighbors,” tells Sayad. After her mother died, Anzhela had to face a problem that proved unsolvable. She had to register her apartment in her name. It was not even an apartment, but a room in a communal apartment that she shared with other people. But her neighbors had already privatized the remaining portion of that apartment, and now they had to boot and drum out this lonely and helpless woman driving her away from the room she occupied. <…> The Civil Registry Office refused to accept her documents because Anzhela was Armenian. Her problems aggravated. Later on, her neighbors burst into her room and severely brutalized her. The only one she could call was Sayad. “When I called the ambulance and mentioned her name, they refused to come over. Then I had to call again and give them my own mother’s first and second names”, told us Sayad.123

Elvira Movsesyan: Elvira Vladimirovna Movsesyan is one of such people. <…> For several years now, she has been trying to leave Azerbaijan, without any success. Elvira has no documents and therefore, she is next to no one. She was born in 1968 in Sharur District of Nakhichevan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (now: Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan). She was born to Armenian father and Azerbaijani mother. <…> In 1990, her father traveled to Armenia to figure out the situation there. After staying there for about a month, he realized that he was not welcome in Armenia as his wife was Azerbaijani. In addition, he had no knowledge of either Russian or Armenian and could speak only Azerbaijani. <…> Shortly after that, my brothers got a visit from the law-enforcement officers. They told them to leave immediately threatening to arrest them on false charges and have them sentenced to lengthy imprisonment <…>. Our neighbors divided in two factions. Some of them helped us, while others were bellicose and requested that we leave. <…> We could not leave the house and were stuck indoors. <…> In 1999, Elvira decided to take her mother’s last name. “Our mother, a poor old woman, put together all the necessary paperwork, but passport department refused to take them. The authorities did not even examine the documents. Moreover, they took Elvira’s Soviet passport along with the paperwork that her mother had put together.124

No one, not even Azerbaijani researchers125, know the real number of such people and their subsequent fate. Yet, a small number of publications and reports prepared by international organizations can give a glimpse of their living conditions.

In Baku, the paramedics of the Ministry of Emergency Situations discovered the body of an elderly Armenian woman. The paramedics of the Ministry of Emergency Situations discovered a body of an elderly woman in Surakhany District of Baku. As 1news.az was informed by the press service of the Ministry of Emergency Situations, their hot-line 112 received an alert that Rosa Baykovna Bagdasarova (born in 1934) had not answered a knocks on the door and telephone calls for a long time. The rescue team of the Ministry arrived quickly on site. They penetrated R. Bagdasarova’s apartment on the sixth floor through the balcony of a neighboring apartment. In the apartment, they found the lifeless body of its owner. A medical team was called in to certify the death. The Police Department of Surakhany District informed 1news.az that the 79-year-old woman was an ethnic Armenian and died of natural causes.126

After examining the problems of ethnic Armenians living in Azerbaijan, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) in its report for 2011127 states that the number of people of Armenian descent in Azerbaijan fluctuates between 700 and 30,000128 persons. These people are divested of the opportunity to exercise their rights as citizens of Azerbaijan and do not enjoy social protection. They never applied to receive Azerbaijani passports in exchange for Soviet passports and today can be virtually described as stateless persons.