полная версия

полная версияArmenophobia in Azerbaijan

Anzhela Elibegova, Armine Adibekian

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Translation by Armen Ayvazyan

Editing by Armen Ayvazyan

A. Adibekyan, A. Elibegova

© “Information and Public Relations Center” of the Administration of the President of the Republic of Armenia

Opening Remarks

The idea of this book came after the presentation of Azeriсhild project which represented a systematized compilation of works by Azerbaijani authors intended for children audiences along with a series of examples of works created by children themselves, which gave a clear demonstration of the gap between the real situation in the Azerbaijani society about anything relating to Armenia and the declared tolerance for diversity of cultures and religions.

Naturally enough, we tend to label this hatred as armenophobia often without full awareness of the pivotal role it plays in shaping the ethnic identity of Azerbaijanis; such hatred channeled against all that pertains to Armenia stands as the nemesis of their psychological model and fuels the juxtaposition of us vs. them which is fraught with repercussions for Azerbaijanis themselves.

The large archive compiled by the authors of this book a) serves as a thesaurus for an analysis of ongoing processes in the Azerbaijani society and b) allows building a temporal perspective on three levels by covering the past history, current situation and expected ramifications of the armenophobic policy pursued at the state level in Azerbaijan.

The book contains necessary factual evidence and theoretical premises that can be viewed as illustrative of the psychological and social basis underpinning the processes that occur in the Azerbaijani society and have some bearing on us. The chance to scrutinize online the phenomenon of armenophobia in the social milieu of Azerbaijan facilitates the work of specialists and becomes a continuous resource for analysis.

The authors are certainly far from the allegation that the Armenian society – if taken under a rigorous scrutiny – will not display similar traits. However, it must be emphasized that the scale and level of such propaganda defy all reasonable comparison in the first place.

The book provides overwhelming evidence attesting to a widespread armenophobia in Azerbaijan and beyond its borders – orchestrated and inspired by the state while represented by its existing political forces with the full approval and support of the intellectual elite and the society as a whole. In this context, there is a blatant contradiction between the verbal statements declaring commitment to certain values and a very specific line of action that nullifies them. Secondly, the book aims exclusively to narrate facts without recourse to any hasty conclusions, partial assessments or biased analysis.

It must be stressed that all examples included in the book are taken from Azerbaijani or neutral sources. The limitations of this publication warrant the inclusion of only the most typical and common manifestations of armenophobia in Azerbaijan. Besides, considering the frequent practice employed by the Azerbaijani media consisting in removal of materials from original sources, the authors have prepared screen shots for all examples used in the book.

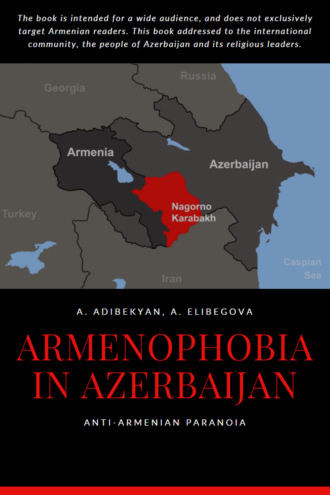

The book is intended for a wide audience, and does not exclusively target Armenian readers. We address this book to the international community, the people of Azerbaijan and its religious leaders.

It is incumbent on us to warn that showing retaliatory xenophobia is inadmissible; therefore, this book is not intended for use as a teaching material in schools and is not recommended for highly sensitive readers.

And, of course, we wish to express our special gratitude to all those whose assistance and support contributed to the publication of this book.

The authors also recommend several thematic websites created upon the initiative of the Information and Public Relations Center of the Administration of the President of the Republic of Armenia by its experts

http://karabakhrecords.info

http://maragha.org

http://azerichild.info

http://xocali.net

http://ermenihaber.am

http://xocali.tv

http://justiceforkhojaly.tv

Armine Adibekyan, Head of the Xenophobia Prevention Initiative NGOAnzhela Elibegova, Candidate of Political Sciences, expert on the geopolitics of the South Caucasus

1. What is important to know about xenophobia?

The complex notion of xenophobia can lend itself to a scrutiny under diverse perspectives of such sciences as biology, medicine, psychology, sociology, ethnology, political science, cultural studies and other related disciplines, yet regardless of its aspects it boils down to an antagonistic perception of others vs. your own kind.

No real threat from the ‘others’ must necessarily be present to trigger off the xenophobia complex as it is intended to bring together the members of any specific community, therefore any similar marking will suffice to serve a key indicator distinguishing between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

The sense of affiliation with a community (i.e. family, tribe, religious, professional, cultural or ethnic group) is a core human need.1 Being part of an ethnic community ranks high among top needs in the self-identification of any individual. Therefore, everything that cannot be framed into the historical concept of ethnic self-identification may elicit individual feelings of rejection, negation, exclusion and opposition.

The conflictologist Christopher Mitchell2 in his study of primary self-identification comes up with the following socio-psychological findings.

• Affiliation with a large group meets the need felt by every individual to be accepted by others.

• Identification with any particular group is instrumental in building self-esteem and sense of security; therefore it is of preference that the group in question be successful from the perspective of its individual members.

• Individuals shun any negative opinions in respect of their own group, as it relates to their wish to maintain a high self-esteem; In their ambition to build a high self-esteem individuals are likely to glorify their group and overlook information on its actions or qualities that can put the group or its members in a bad light.

• The division into ‘us’ and ‘them’ is almost inevitably bound to debase ‘them’ so that ‘us’ can be hailed by the same token;

• Group identification is often so strong that the values and objectives of the group are internalized and assimilated by its individual members.

• Any threat to the group or any of its values and goals will be regarded by its members as a personal threat putting their own values at risk.

The awareness of pitting ‘us’ against ‘them’ occurs through close ties, such as:

• family, kinship, blood ties (tribe, clan, family);

• ethnicity (people, ethnic group, nation);

• language (language, dialect, vernacular);

• creed (religion, sectarian groups);

• social affiliation (community, estate, class, group).

‘One of us’ is a holder of models that form and govern the conduct within a single community as inherited from previous generations and replicated by generations that follow.

The ‘others’ are associated with fear, alleged trouble and change – not infrequently for worse. Change, aggression, invasion and destruction are in direct association with the concept of ‘others’ and set the foundation underlying the picture of the world formed by virtually all peoples. This statement is true not only for relations between individuals and groups but also covers the interaction of the human being with nature (natural phenomena, wild animals, etc.). Social psychologists G.U. Soldatova and A. V. Makarchuk hold the view that more often the attitude towards ‘aliens’ is dominated by fear.3 Historically, people have always treated arcane, unknown and new things with apprehension. According to Erich Fromm, this fear, which may later translate into suspiciousness and culminate in rejection, can be traced back to the need of making ‘extraordinary decisions’.4

According to some authors, the concept of ‘alien’ cannot be simply equated with the concepts of ‘opposed’, ‘other’ or ‘enemy’, but serves as an axis that lends sense to the concept of ‘one of our own’. People who live in homogeneous environments rarely reflect on their identity seeing the world framed into a shared ideologies, perceptions and behavioral patterns. Only after they face an alternative and become aware of their differences, do they form a picture of their own kind and identify themselves as bearers of their ‘own’ system.

People’s view and evaluation of ‘aliens’ spring from their own customs, traditions and lines of conduct. The concept of ‘us’ (‘one of our kind’, ‘friends’, ‘desirables’) has been carved by chiseling out ‘them’ (‘enemies’, ‘aliens’, ‘undesirables’). People have long been able to build awareness of the specifics of their own ethnic group only through comparison and contrast with others.5

‘Aliens’ can be classified as follows:

‘Remote aliens’ are a group known to exist but with so far no contacts established or vital interests affected due to geographical, historical and other reasons. This category evokes neutral and descriptive attitude that is free from negative implications and according to Igor Kon ‘arouses curiosity’ (contacts between Armenians and Eskimos, Georgians and Uighurs, Bushmen and Sioux).

Friendly aliens are a group with a shared history of cooperation, intensive contact, overcoming the same calamities and joining forces in warfare against common enemies. The perception of this category of ‘aliens’ takes on a positive hue with their differences well known, thoroughly examined, accepted and viewed favorably (contacts between Armenians and Assyrians, Armenians and Greeks, Azerbaijanis and Turks, etc.). Soldatova defines this category rather as ‘others’ than ‘aliens’. “They both attract and repel at the same time. By itself, such emotional duality is free from negative connotations, and the odds are always high that such ‘other-alien’ may become a ‘one of our own’.6

Nearby alien represent a group located in the immediate vicinity, where a history of conflicts, confrontation and struggle underlies the relations with this group. This may refer to warring tribes, states or opposing systems, which according to G. Soldatova can be defined as ‘hostile’. Therefore, ‘hostile-aliens’ are usually shunned, rejected, blamed for all calamities and disasters; frequently they are targeted as enemies and hated. And, should the rational fear of the unknown degenerate into such manifestations, then we come to deal with nothing short of xenophobia – fear of aliens, feelings of hatred and animosity towards ‘alien’ individuals and groups which differ from us”.7 The perception of ‘hostile-aliens’ is characterized by negative hues and mutually aggressive attitudes that last. ‘Hostile aliens’ are groups which live, as a rule, in the immediate vicinity of each other (share a border) and sometimes within the same community (relations between the national or religious minorities and the majority).

It must be noted that the transition from the second category of ‘aliens’ to the third category is rather commonplace. Familiar, close and not numerous as they are, they may be in need of protection and defense. However, as ‘aliens’ evolve to the extent of wanting to break off, take charge of their own problems and meet their needs on equal footing with the majority, they may be immediately labeled as ‘hostile enemies’. Qualities previously regarded in a positive vein may become tinged with entirely opposite feelings.

Repelling alien elements hinges on the importance of the global goal. For instance, the ethnic differentiation of own kind vs. aliens lies along the lines: “We are Armenians” or “We are Lezgins”. But within the same ethnic group, identical processes may occur on subethnic or territorial levels, such as: Lezgins of Azerbaijan vs. Legzins of Dagestan, Cristian Armenians vs. Muslim Armenians, which can further break into factions based on the local vernacular, region or a patron saint worshiped. Consolidation or exclusion varies depending on the goal or status of the ‘alien’ in the context of the problem at hand.

The interaction between the groups on the basis of their distinctions can be as follows:

• Biological – based on the survival instinct.

• Psychological – based on the perception of the other group and the processes that it entails, such as: patterns of thinking, fears, motives, etc., that form attitudes and behavior.

• Socio-psychological – based on the differentiation occurring within the society and the social processes that it entails.

• Political – based on the role and responsibility of the authorities in shaping the public opinion and ways to cultivate or thwart xenophobic tendencies.

The biological aspect

The origins of xenophobia have been traditionally traced back to biological characteristics, where the rejection of an ‘alien’ is seen as an instinctive survival mechanism for preserving the kind and species. Those ‘of own kind’ are protected from extinction as scarce resources are relentlessly fought over.8

However, seeking to justify human behavior by biological factors only is highly contentious. Throughout the history, social structures were governed by placing taboos and bans on natural biological instincts through religious, moral, administrative and legal provisions. A. Tsiurupa maintains the view that “such an instinct is pernicious and pointless in the human society”.9 This comes to say that an entire universe of differences separates the animal world and the human society, and therefore biology may not be referred to as an excuse for any conduct which the human society flags as detrimental.

Psychological and socio-psychological aspect

Xenophobia is an irrational sentiment and a source of an entire set of negative individual emotions hinging on fears, prejudices, stereotypes, biased judgments and all ensuing states and behavioral patterns.

Xenophobia is based on anticipated risks and fears springing from a twisted perception of the reality rather than any objective circumstances. Suspected existence of external and quite specific forces responsible for adverse effects occurring within ‘own’ society and putting its very existence at risk is referred to in support of allegations of ill intent on the part of ‘aliens’.

The surrounding world is seen as a ‘pyramid of threats’ with the enemy’s incarnation placed at its top and possessing destructive traits, objectives and instruments. The “enemy” can manipulate the surrounding environment (by enchanting, bribing, slandering or lobbying) and makes use of these capabilities and capacities to influence the destructive processes within the society. The mirror image of this pyramid represents the prism, through which the reality is seen, and which comprises attitudes, stereotypes and projections cultivating the image of an enemy. This process is followed by frustration which leads to aggression and repression.

Frustration is a psychological condition occurring where there are no or limited possibilities to meet one’s needs and causing a feeling of deprivation over what is aspired for. The theory of aggression and frustration maintains that the frustrated condition leads to an aggression directed against the actual or purported source of frustration, any other third party or even against own self.10

In Azerbaijan, for instance, ‘Karabakh’ is usually considered to be such source of frustration (standing collectively for a military defeat, the negotiation process, attempts to win it back, absence of a promised war) where Armenians as ethnic group are labeled as its cause, regardless of their place of residence, nationality, sex, age, and social status.

Aggression – is a deliberate action or rhetoric, meant to cause damage or offense to its target. The aggression may occur unaccompanied by action; it can manifest itself in rhetoric, fantasizing, dreams or even in a thoroughly meditated retaliation plan,11 such as vociferating insults in the press, threats of blasting nuclear power plants or shooting down civilian aircrafts, wishful thinking on “celebrating the next Nowruz in Shusha”, public discussion of incursion plans and hostilities.

There are several ways of externalizing aggression:12

Redirection against the recognized cause of frustration – Karabakh and Armenia, including their inhabitants, who are labeled as “separatists”, “aggressors” and “occupying forces”.

Redirection against absolutely innocent targets – at the end of the twentieth century, the Armenian population of Sumgait, Baku and Kirovabad, while not being the supporters of the Miatsum ideology (demands to transfer Nagorno-Karabakh under the Armenian jurisdiction), fell victim to pogroms in Azerbaijan because of their compatriots’ actions in Karabakh only on the grounds of their Armenian ethnicity. In the aftermath of the war, this aggression was further extended to those, who, according to the official Baku were pro-Armenian and therefore supported anti-Azerbaijan policy; we refer to the infamous ‘Black list’, which will be discussed later.

Transferring inside own society, i.e. redirection against own self – the search for internal “Armenian enemies”, suppressing the dissidence and authoritarianism resulting in an increased rate of suicides and homicides (domestic murders and political assassinations).

Also, ethnic attitudes/mindsets form part of the socio-psychological dimension. This refers to a person’s propensity to perceive individual aspects of the life of the nation and relations between nations as well as to act in a certain way in a particular situation, in accordance with such perceptions.13

There are three types of attitudes/mindsets:

Positive: overestimation of positive qualities;

Negative: overestimation of negative qualities;

Adequate: a balanced approach in evaluating some characteristics.

The formulation of attitudes/mindsets falls under the impact of the attitudes/mindsets instilled by parents (similarities between attitudes of parents and children on socially significant subjects), persons of high repute and the mass media. All of these serve as agents of education, propaganda and ideology in shaping the needed stereotype.

Grandfather to his grandson: The Armenians are our enemies, son. These accursed people have been blighting our lives for 5 years now fouling up everything with their venom. Once, we accepted them into our service as farm hands and servants. We gave them land, housing and shelter. They grew on our scraps. Let them be damned for abusing our kindness. As insolent dogs bark at their masters, so did they pay us back with a vile ingratitude to bite those who lent them a hand and supported them in times of hardship. These scoundrels and bastards bark at those who gave them bread and refuge14.15

Azad Sharif, a veteran of Azerbaijani journalism: We must shout this message loud and clear so that our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren may hear us and avoid the mistakes of our fathers and our own. Let them never trust Armenians again and give them the chance to do another Khojaly16! Heed my words, in half a century they will once again knock at our doors offering their treacherous friendship, begging for our trust, repenting their sins and trying to win our favor with their sweet talk. Children! Grandchildren! And great-grandchildren! Never forget this!”

Frequently, these attitudes/mindsets are generated on the basis of a successful or failed communication experience with a representative of some group. Ethnic attitudes/mindsets, just like any others, underpin the common misconceptions on others. However, they are susceptible to change under temporal or situational factors; this can be accomplished through collecting sufficient knowledge about the subject, personal contacts or altering the ideological milieu.

Mirmekhti Agaoghlu: In this way, the hatred inside me gradually transformed into a complex of insignificance. I felt upset over being lied to for so long.

Out of pure interest, I began communicating with some Armenian girls on the website www.mail.ru. They used to tell me: “Your guys are so rude, ill-mannered and immoral; they use obscene language and insult”. I tried to show some civilized manners. <…> I told these girls, that I am different and not like them.

Sometimes, we talked about the war. We tried to figure out who was right, who was to blame, while forgetting that resolution of this conflict was up to the presidents, and not us. And when we realized this simple truth, the bombast dissipated, and our conversation returned to the regular subject of simple things in our lives. <…> The years of our childhood saw crowds rushing into streets for rallies, and ever since we have been creating the great Armenian foe by nurturing, elaborating and fueling its growth. In the end, we made it so big that we started seeing only what we wanted to see rather than the reality. <…> but every time we get to know who our enemies are and what they are capable of, we are up for a shock.17

In their turn, ethnic attitudes/mindsets underlie the ethnic stereotyping, which constitutes an interaction element based on the experience of previous generations which serve as a source of human views and perceptions.

Stereotype is a set of views that reflects the attitudes/mindsets of a social group in respect of a specific phenomenon or another social group. Ethnic stereotype is a firmly ingrained attitude/mindset that directly affects how the surrounding people are perceived and how their behavior is interpreted. Stereotyping is a convenient way of classifying and systematizing information. Ethnic stereotypes are associated with a generalized and schematized description of the properties and characteristics of one’s own ethnic community (autostereotypes) and those of an alien ethnic community (heterostereotypes).18

The present research revealed the dominant stereotypes in Azerbaijan, which are as follows:

Azerbaijani autostereotypes: very ancient, cultured, civilized, hospitable, trusting, forgiving, hard-working, talented, creative, honest, decent, proud, courageous, patriotic and tolerant people.

Kenan Guluzadeh: Azerbaijanis is truly gentle nation, far from any gratuitous aggressiveness, let alone any deliberate cultivation or incitement of religious hatred and national or ethnic strife. These are not just lofty words, but the reality that we all know. <…> We can feel no hatred towards the people who live in the neighboring countries, and this includes Armenians. Indeed, we may loathe, and perhaps rightfully do so, some nationalist circles in Armenia. <…> But we are not capable of hating an entire nation, simply because a human soul cannot house so much hatred. <…> Xenophobia is foreign to the Azerbaijani society. We are all Azerbaijani, and we have no other motherland.19

Heterostereotypes of Armenians – vile, perfidious, lying, bloodthirsty, thieving, untalented, ungrateful, greedy, mercenary, scheming, petty merchants and perjurers.

Azad Sharif, a veteran of Azerbaijani journalism: Let us be honest at least to ourselves and admit the fact that we are an amazingly trusting nation: we bear no grudges and take pride in our multiculturalism. For centuries, our forgiving nature was abused by our treacherous and envious neighbors who shared with us the same courtyard, front door, the city or the village