Полная версия

Lifespan

CRISIS MODE

Wilbur and Orville Wright could never have built a flying machine without a knowledge of airflow and negative pressure and a wind tunnel. Nor could the United States have put men on the moon without an understanding of metallurgy, liquid combustion, computers, and some measure of confidence that the moon is not made of green cheese.7

In the same way, if we are to make real progress in the effort to alleviate the suffering that comes with aging, what is needed is a unified explanation for why we age, not just at the evolutionary level but at the fundamental level.

But explaining aging at a fundamental level is no easy task. It will have to satisfy all known laws of physics and all rules of chemistry and be consistent with centuries of biological observations. It will need to span the least understood world between the size of a molecule and the size of a grain of sand,8 and it should explain simultaneously the simplest and the most complex living machines that have ever existed.

It should, therefore, come as no surprise that there has never been a unified theory of aging, at least not one that has held up—though not for lack of trying.

One hypothesis, proposed independently by Peter Medawar and Leo Szilard, was that aging is caused by DNA damage and a resulting loss of genetic information. Unlike Medawar, who was always a biologist, who built a Nobel Prize–winning career in immunology, Szilard had come to study biology in a roundabout way. The Budapest-born polymath and inventor lived a nomadic life with no permanent job or address, preferring to spend his time staying with colleagues who satisfied his mental curiosities about the big questions facing humanity. Early in his career, he was a pioneering nuclear physicist and a founding collaborator on the Manhattan Project, which ushered in the age of atomic warfare. Horrified by the countless lives his work had helped end, he turned his tortured mind toward making life maximally long.9

The idea that mutation accumulation causes aging was embraced by scientists and the public alike in the 1950s and 1960s, at a time when the effects of radiation on human DNA were on a lot of people’s minds. But although we know with great certainty that radiation can cause all sorts of problems in our cells, it causes only a subset of the signs and symptoms we observe during aging,10 so it cannot serve as a universal theory.

In 1963, the British biologist Leslie Orgel threw his hat into the ring with his “Error Catastrophe Hypothesis,” which postulated that mistakes made during the DNA-copying process lead to mutations in genes, including those needed to make the protein machinery that copies DNA. The process increasingly disrupts those same processes, multiplying upon themselves until a person’s genome has been incorrectly copied into oblivion.11

Around the same time that Szilard was focusing on radiation, Denham Harman, a chemist at Shell Oil, was also thinking atomically, albeit in a different way. After taking time off to finish medical school at Stanford University, he came up with the “Free Radical Theory of Aging,” which blames aging on unpaired electrons that whiz around within cells, damaging DNA through oxidation, especially in mitochondria, because that is where most free radicals are generated.12 Harman spent the better part of his life testing the theory.

I had the pleasure of meeting the Harman family in 2013. His wife told me that Professor Harman had been taking high doses of alphalipoic acid for most of his life to quench free radicals. Considering that he worked tirelessly on his research well into his 90s, I suppose, at the very least, it didn’t hurt.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Harman and hundreds of other researchers tested whether antioxidants would extend the lifespan of animals. The results overall were disappointing. Although Harman had some success increasing the average lifespan of rodents, such as with the food additive butylated hydroxytoluene, none showed an increase in maximum lifespan. In other words, a cohort of study animals might live a few weeks longer, on average, but none of the animals was setting records for individual longevity. Science has since demonstrated that the positive health effects attainable from an antioxidant-rich diet are more likely caused by stimulating the body’s natural defenses against aging, including boosting the production of the body’s enzymes that eliminate free radicals, not as a result of the antioxidant activity itself.

If old habits die hard, the free-radical idea is heroin. The theory was overturned by scientists within the cloisters of my field more than a decade ago, yet it is still widely perpetuated by purveyors of pills and drinks, who fuel a $3 billion global industry.13 With all that advertising, it is not surprising that more than 60 percent of US consumers still look for foods and beverages that are good sources of antioxidants.14

Free radicals do cause mutations. Of course they do. You can find mutations in abundance, particularly in cells that are exposed to the outside world15 and in the mitochondrial genomes of old individuals. Mitochondrial decline is certainly a hallmark of aging and can lead to organ dysfunction. But mutations alone, especially mutations in the nuclear genome, conflict with an ever-increasing amount of evidence to the contrary.

Arlan Richardson and Holly Van Remmen spent about a decade at the University of Texas at San Antonio testing if increasing free-radical damage or mutations in mice led to aging; it didn’t.16 In my lab and others, it has proven surprisingly simple to restore the function of mitochondria in old mice, indicating that a large part of aging is not due to mutations in mitochondrial DNA, either, at least not until late in life.17

Although the discussion about the role of nuclear DNA mutations in aging continues, there is one fact that contradicts all these theories, one that is difficult to refute.

Ironically, it was Szilard, in 1960, who initiated the demise of his own theory by figuring out how to clone a human cell.18 Cloning gives us the answer as to whether or not mutations cause aging. If old cells had indeed lost crucial genetic information and this was the cause of aging, we shouldn’t be able to clone new animals from older individuals. Clones would be born old.

It’s a misconception that cloned animals age prematurely. It has been widely perpetuated in the media and even the National Institutes of Health website says so.19 Yes, it’s true that Dolly, the first cloned sheep, created by Keith Campbell and Ian Wilmut at the Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh, lived only half a normal lifespan and died of a progressive lung disease. But extensive analysis of her remains showed no sign of premature aging.20 Meanwhile, the list of animal species that have been cloned and proven to live a normal, healthy lifespan now includes goats, sheep, mice, and cows.21

Because of the fact that nuclear transfer works in cloning, we can say with a high degree of confidence that aging isn’t caused by mutations in nuclear DNA. Sure, it’s possible that some cells in the body don’t mutate and those are the ones that end up making successful clones, but that seems highly unlikely. The simplest explanation is that old animals retain all the requisite genetic information to generate an entirely new, healthy animal and that mutations are not the primary cause of aging.22

It’s certainly no dishonor to those brilliant researchers that their theories haven’t withstood the test of time. That’s what happens to most science, and perhaps all of it eventually. In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn noted that scientific discovery is never complete; it goes through predictable stages of evolution. When a theory succeeds at explaining previously unexplainable observations about the world, it becomes a tool that scientists can use to discover even more.

Inevitably, however, new discoveries lead to new questions that are not entirely answerable by the theory, and those questions beget more questions. Soon the model enters crisis mode and begins to drift as scientists seek to adjust it, as little as possible, to account for that which it cannot explain.

Crisis mode is always a fascinating time in science but one that is not for the faint of heart, as doubts about the views of previous generations continue to grow against the old guard’s protestations. But the chaos is ultimately replaced by a paradigm shift, one in which a new consensus model emerges that can explain more than the previous model.

That’s what happened about a decade ago, as the ideas of leading scientists in the aging field began to coalesce around a new model—one that suggested that the reason so many brilliant people had struggled to identify a single cause of aging was that there wasn’t one.

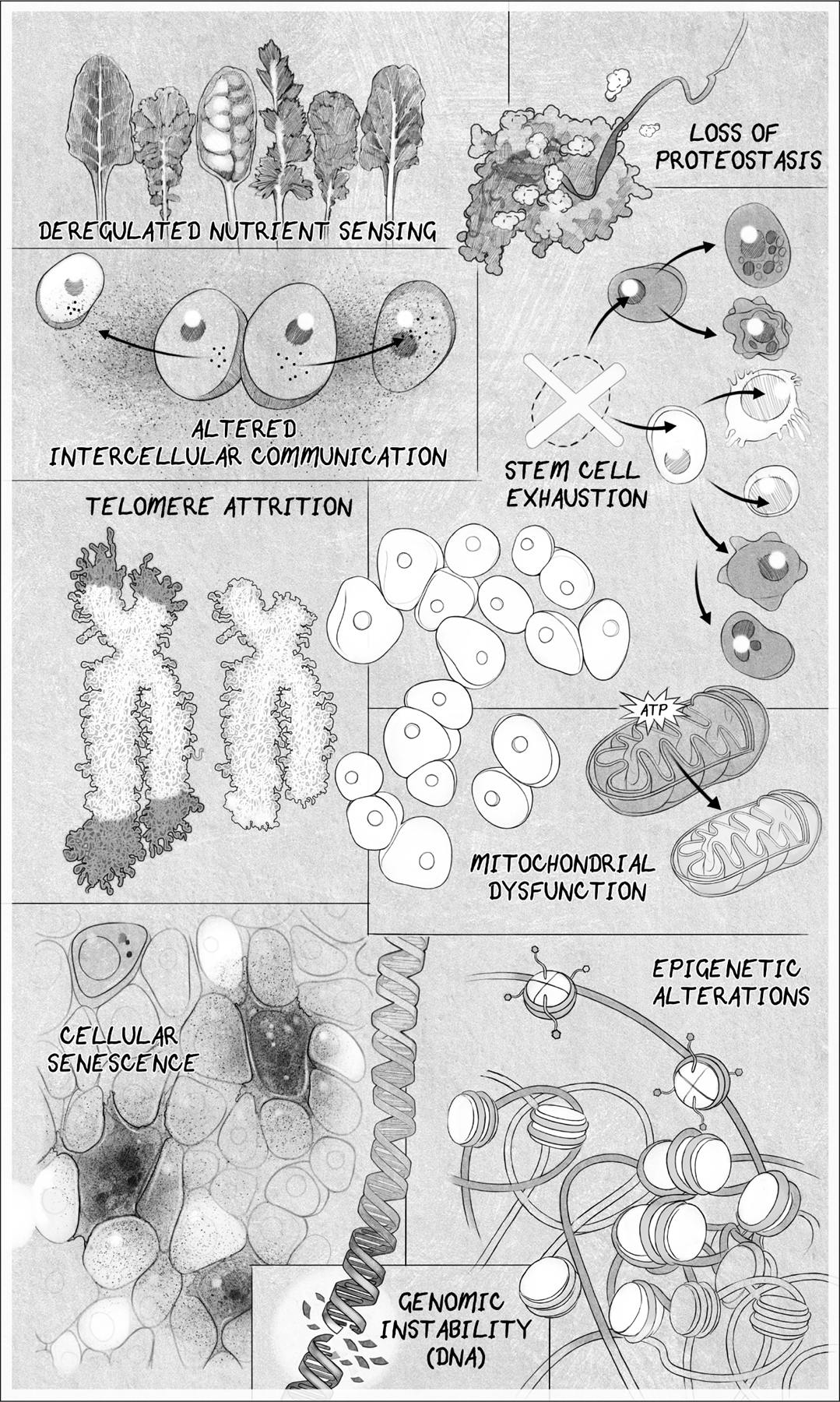

In this more nuanced view, aging and the diseases that come with it are the result of multiple “hallmarks” of aging:

Genomic instability caused by DNA damage

Attrition of the protective chromosomal endcaps, the telomeres

Alterations to the epigenome that controls which genes are turned on and off

Loss of healthy protein maintenance, known as proteostasis

Deregulated nutrient sensing caused by metabolic changes

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Accumulation of senescent zombielike cells that inflame healthy cells

Exhaustion of stem cells

Altered intercellular communication and the production of inflammatory molecules

Researchers began to cautiously agree: address these hallmarks, and you can slow down aging. Slow down aging, and you can forestall disease. Forestall disease, and you can push back death.

Take stem cells, which have the potential to develop into many other kinds of cells: if we can keep these undifferentiated cells from tiring out, they can continue to generate all the differentiated cells necessary to heal damaged tissues and battle all kinds of diseases.

Meanwhile, we’re improving the rates of acceptance of bone marrow transplants, which are the most common form of stem cell therapy, and using stem cells for the treatment of arthritic joints, type 1 diabetes, loss of vision, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. These stem cell–based interventions are adding years to people’s lives.

Or take senescent cells, which have reached the end of their ability to divide but refuse to die, continuing to spit out panic signals that inflame surrounding cells: if we can kill off senescent cells or keep them from accumulating in the first place, we can keep our tissues much healthier for longer.

The same can be said for combating telomere loss, the decline in proteostasis, and all of the other hallmarks. Each can be addressed one by one, a little at a time, in ways that can help us extend human healthspans.

Over the past quarter century, researchers have increasingly honed their efforts in on addressing each of these hallmarks. A broad consensus formed that this would be the best way to alleviate the pain and suffering of those who are aging.

There is little doubt that the list of hallmarks, though incomplete, comprises the beginnings of a rather strong tactical manual for living longer and healthier lives. Interventions aimed at slowing any one of these hallmarks may add a few years of wellness to our lives. If we can address all of them, the reward could be vastly increased average lifespans.

As for pushing way past the maximum limit? Addressing these hallmarks might not be enough.

But the science is moving fast, faster now than ever before, thanks to the accumulation of many centuries of knowledge, robots that analyze tens of thousands of potential drugs each day, sequencing machines that read millions of genes a day, and computing power that processes trillions of bytes of data at speeds that were unimaginable just a decade ago. Theories on aging, which were slowly chipped away for decades, are now more easily testable and refutable.

Although it is in its early days, a new shift in thinking is again under way. Once again we find ourselves in a period of chaos—still quite confident that the hallmarks are accurate indicators of aging and its myriad symptoms but unable to explain why the hallmarks occur in the first place.

THE HALLMARKS OF AGING. Scientists have settled on eight or nine hallmarks of aging. Address one of these, and you can slow down aging. Address all of them, and you might not age.

It is time for an answer to this very old question.

Now, finding a universal explanation for anything—let alone something as complicated as aging—doesn’t happen overnight. Any theory that seeks to explain aging must not just stand up to scientific scrutiny but provide a rational explanation for every one of the pillars of aging. A universal hypothesis that seems to provide a reason for cellular senescence but not stem cell exhaustion would, for example, explain neither.

Yet I believe that such an answer exists—a cause of aging that exists upstream of all the hallmarks. Yes, a singular reason why we age.

Aging, quite simply, is a loss of information.

You might recognize that loss of information was a big part of the ideas that Szilard and Medawar independently espoused, but it was wrong because it focused on a loss of genetic information.

But there are two types of information in biology, and they are encoded entirely differently. The first type of information—the type my esteemed predecessors understood—is digital. Digital information, as you likely know, is based on a finite set of possible values—in this instance, not in base 2 or binary, coded as 0s and 1s, but the sort that is quaternary or base 4, coded as adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine, the nucleotides A, T, C, G of DNA.

Because DNA is digital, it is a reliable way to store and copy information. Indeed, it can be copied again and again with tremendous accuracy, no different in principle from digital information stored in computer memory or on a DVD.

DNA is also robust. When I first worked in a lab, I was shocked by how this “molecule of life” could survive for hours in boiling water and thrilled that it was recoverable from Neanderthal remains at least 40,000 years old.23 The advantages of digital storage explain why chains of nucleic acids have remained the go-to biological storage molecule for the past 4 billion years.

The other type of information in the body is analog.

We don’t hear as much about analog information in the body. That’s in part because it’s newer to science, and in part because it’s rarely described in terms of information, even though that’s how it was first described when geneticists noticed strange nongenetic effects in plants they were breeding.

Today, analog information is more commonly referred to as the epigenome, meaning traits that are heritable that aren’t transmitted by genetic means.

The term epigenetics was first coined in 1942 by Conrad H. Waddington, a British developmental biologist, while working at Cambridge University. In the past decade, the meaning of the word epigenetics has expanded into other areas of biology that have less to do with heredity—including embryonic development, gene switch networks, and chemical modifications of DNA-packaging proteins—much to the chagrin of orthodox geneticists in my department at Harvard Medical School.

In the same way that genetic information is stored as DNA, epigenetic information is stored in a structure called chromatin. DNA in the cell isn’t flailing around disorganized, it is wrapped around tiny balls of protein called histones. These beads on a string self-assemble to form loops, as when you tidy your garden hose on your driveway by looping it into a pile. If you were to play tug-of-war using both ends of a chromosome, you’d end up with a six foot-long string of DNA punctuated by thousands of histone proteins. If you could somehow plug one end of the DNA into a power socket and make the histones flash on and off, a few cells could do you for holiday lights.

In simple species, like ancient M. superstes and fungi today, epigenetic information storage and transfer is important for survival. For complex life, it is essential. By complex life, I mean anything made up of more than a couple of cells: slime molds, jellyfish, worms, fruit flies, and of course mammals like us. Epigenetic information is what orchestrates the assembly of a human newborn made up of 26 billion cells from a single fertilized egg and what allows the genetically identical cells in our bodies to assume thousands of different modalities.24

If the genome were a computer, the epigenome would be the software. It instructs the newly divided cells on what type of cells they should be and what they should remain, sometimes for decades, as in the case of individual brain neurons and certain immune cells.

That’s why a neuron doesn’t one day behave like a skin cell and a dividing kidney cell doesn’t give rise to two liver cells. Without epigenetic information, cells would quickly lose their identity and new cells would lose their identity, too. If they did, tissues and organs would eventually become less and less functional until they failed.

In the warm ponds of the primordial Earth, a digital chemical system was the best way to store long-term genetic data. But information storage was also needed to record and respond to environmental conditions, and this was best stored in analog format. Analog data are superior for this job because they can be changed back and forth with relative ease whenever the environment within or outside the cell demands it, and they can store an almost unlimited number of possible values, even in response to conditions that have never been encountered before.25

The unlimited number of possible values is why many audiophiles still prefer the rich sounds of analog storage systems. But even though analog devices have their advantages, they have a major disadvantage. In fact, it’s the reason we’ve moved from analog to digital. Unlike digital, analog information degrades over time—falling victim to the conspiring forces of magnetic fields, gravity, cosmic rays, and oxygen. Worse still, information is lost as it’s copied.

No one was more acutely disturbed by the problem of information loss than Claude Shannon, an electrical engineer from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston. Having lived through World War II, Shannon knew firsthand how the introduction of “noise” into analog radio transmissions could cost lives. After the war, he wrote a short but profound scientific paper called “The Mathematical Theory of Communication” on how to preserve information, which many consider the foundation of Information Theory. If there is one paper that propelled us into the digital, wireless world in which we now live, that would be it.26

Shannon’s primary intention, of course, was to improve the robustness of electronic and radio communications between two points. His work may ultimately prove to be even more important than that, for what he discovered about preserving and restoring information, I believe, can be applied to aging.

Don’t be disheartened by my claim that we are the biological equivalent of an old DVD player. This is actually good news. If Szilard had turned out to be right about mutations causing aging, we would not be able to easily address it, because when information is lost without a backup, it is lost for good. Ask anyone who’s tried to play or restore content from a DVD that’s had an edge broken off: what is gone is gone.

But we can usually recover information from a scratched DVD. And if I am right, the same kind of process is what it will take to reverse aging.

As cloning beautifully proves, our cells retain their youthful digital information even when we are old. To become young again, we just need to find some polish to remove the scratches.

This, I believe, is possible.

A TIME TO EVERY PURPOSE

The Information Theory of Aging starts with the primordial survival circuit we inherited from our distant ancestors.

Over time, as you might expect, the circuit has evolved. Mammals, for instance, don’t have just a couple of genes that create a survival circuit, such as those that first appeared in M. superstes. Scientists have found more than two dozen of them within our genome. Most of my colleagues call these “longevity genes” because they have demonstrated the ability to extend both average and maximum lifespans in many organisms. But these genes don’t just make life longer, they make it healthier, which is why they can also be thought of as “vitality genes.”

Together, these genes form a surveillance network within our bodies, communicating with one another between cells and between organs by releasing proteins and chemicals into the bloodstream, monitoring and responding to what we eat, how much we exercise, and what time of day it is. They tell us to hunker down when the going gets tough, and they tell us to grow fast and reproduce fast when the going gets easier.

And now that we know these genes are there and what many of them do, scientific discovery has given us an opportunity to explore and exploit them; to imagine their potential; to push them to work for us in different ways. Using molecules both natural and novel, using technology both simple and complex, using wisdom both new and old, we can read them, turn them up and down, and even change them altogether.

The longevity genes I work on are called “sirtuins,” named after the yeast SIR2 gene, the first one to be discovered. There are seven sirtuins in mammals, SIRT1 to SIRT7, and they are made by almost every cell in the body. When I started my research, sirtuins were barely on the scientific radar. Now this family of genes is at the forefront of medical research and drug development.

Descended from gene B in M. superstes, sirtuins are enzymes that remove acetyl tags from histones and other proteins and, by doing so, change the packaging of the DNA, turning genes off and on when needed. These critical epigenetic regulators sit at the very top of cellular control systems, controlling our reproduction and our DNA repair. After a few billion years of advancement since the days of yeast, they have evolved to control our health, our fitness, and our very survival. They have also evolved to require a molecule called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, or NAD. As we will see later, the loss of NAD as we age, and the resulting decline in sirtuin activity, is thought to be a primary reason our bodies develop diseases when we are old but not when we are young.

Trading reproduction for repair, the sirtuins order our bodies to “buckle down” in times of stress and protect us against the major diseases of aging: diabetes and heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis, even cancer. They mute the chronic, overactive inflammation that drives diseases such as atherosclerosis, metabolic disorders, ulcerative colitis, arthritis, and asthma. They prevent cell death and boost mitochondria, the power packs of the cell. They go to battle with muscle wasting, osteoporosis, and macular degeneration. In studies on mice, activating the sirtuins can improve DNA repair, boost memory, increase exercise endurance, and help the mice stay thin, regardless of what they eat. These are not wild guesses as to their power; scientists have established all of this in peer-reviewed studies published in journals such as Nature, Cell, and Science.

And in no small measure, because sirtuins do all of this based on a rather simple program—the wondrous gene B in the survival circuit—they’re turning out to be more amenable to manipulation than many other longevity genes. They are, it would appear, one of the first dominos in the magnificent Rube Goldberg machine of life, the key to understanding how our genetic material protects itself during times of adversity, allowing life to persist and thrive for billions of years.