Полная версия

Lifespan

Those people will tell you that our modern lifestyles have cursed us with shortening lifespans. They’ll say you’re unlikely to see 100 years of age and that your children aren’t likely to get to the century mark, either. They’ll say they’ve looked at the science of it all and done the projections, and it sure doesn’t seem likely that your grandchildren will get to their 100th birthdays, either. And they’ll say that if you do get to 100, you probably won’t get there healthy and you definitely won’t be there for long. And if they grant you that people will live longer, they’ll tell you that it’s the worst thing for this planet. Humans are the enemy!

They’ve got good evidence for all of this—the entire history of humanity, in fact.

Sure, little by little, millennia by millennia, we’ve been adding years to the average human life, they will say. Most of us didn’t get to 40, and then we did. Most of us didn’t get to 50, and then we did. Most of us didn’t get to 60, and then we did.12 By and large, these increases in life expectancy came as more of us gained access to stable food sources and clean water. And largely the average was pushed upward from the bottom; deaths during infancy and childhood fell, and life expectancy rose. This is the simple math of human mortality.

But although the average kept moving up, the limit did not. As long as we’ve been recording history, we have known of people who have reached their 100th year and who might have lived a few years beyond that mark. But very few reach 110. Almost no one reaches 115.

Our planet has been home to more than 100 billion humans so far. We know of just one, Jeanne Calment of France, who ostensibly lived past the age of 120. Most scientists believe she died in 1997 at the age of 122, although it’s also possible that her daughter replaced her to avoid paying taxes.13 Whether or not she actually made it to that age really doesn’t matter; others have come within a few years of that age but most of us, 99.98 percent to be precise, are dead before 100.

So it certainly makes sense when people say that we might continue to chip away at the average, but we’re not likely to move the limit. They say it’s easy to extend the maximum lifespan of mice or of dogs, but we humans are different. We simply live too long already.

They are wrong.

There’s also a difference between extending life and prolonging vitality. We’re capable of both, but simply keeping people alive—decades after their lives have become defined by pain, disease, frailty, and immobility—is no virtue.

Prolonged vitality—meaning not just more years of life but more active, healthy, and happy ones—is coming. It is coming sooner than most people expect. By the time the children who are born today have reached middle age, Jeanne Calment may not even be on the list of the top 100 oldest people of all time. And by the turn of the next century, a person who is 122 on the day of his or her death may be said to have lived a full, though not particularly long, life. One hundred and twenty years might be not an outlier but an expectation, so much so that we won’t even call it longevity; we will simply call it “life,” and we will look back with sadness on the time in our history in which it was not so.

What’s the upward limit? I don’t think there is one. Many of my colleagues agree.14 There is no biological law that says we must age.15 Those who say there is don’t know what they’re talking about. We’re probably still a long way off from a world in which death is a rarity, but we’re not far from pushing it ever farther into the future.

All of this, in fact, is inevitable. Prolonged healthy lifespans are in sight. Yes, the entire history of humanity suggests otherwise. But the science of lifespan extension in this particular century says that the previous dead ends are poor guides.

It takes radical thinking to even begin to approach what this will mean for our species. Nothing in our billions of years of evolution has prepared us for this, which is why it’s so easy, and even alluring, to believe that it simply cannot be done.

But that’s what people thought about human flight, too—up until the moment someone did it.

Today the Wright brothers are back in their workshop, having successfully flown their gliders down the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk. The world is about to change.

And just as was the case in the days leading up to December 17, 1903, the majority of humanity is oblivious. There was simply no context with which to construct the idea of controlled, powered flight back then, so the idea was fanciful, magical, the stuff of speculative fiction.16

Then: liftoff. And nothing was ever the same again.

We are at another point of historical inflection. What hitherto seemed magical will become real. It is a time in which humanity will redefine what is possible; a time of ending the inevitable.

Indeed, it is a time in which we will redefine what it means to be human, for this is not just the start of a revolution, it is the start of an evolution.

PART I

WHAT WE KNOW

(THE PAST)

ONE

VIVA PRIMORDIUM

IMAGINE A PLANET ABOUT THE SIZE OF OUR OWN, ABOUT AS FAR FROM ITS STAR, rotating around its axis a bit faster, such that a day lasts about twenty hours. It is covered with a shallow ocean of salty water and has no continents to speak of—just some sporadic chains of basaltic black islands peeking up above the waterline. Its atmosphere does not have the same mix of gases as ours. It is a humid, toxic blanket of nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide.

There is no oxygen. There is no life.

Because this planet, our planet as it was 4 billion years ago, is a ruthlessly unforgiving place. Hot and volcanic. Electric. Tumultuous.

But that is about to change. Water is pooling next to warm thermal vents that litter one of the larger islands. Organic molecules cover all surfaces, having ridden in on the backs of meteorites and comets. Sitting on dry, volcanic rock, these molecules will remain just molecules, but when dissolved in pools of warm water, through cycles of wetting and drying at the pools’ edges, a special chemistry takes place.1 As the nucleic acids concentrate, they grow into polymers, the way salt crystals form when a seaside puddle evaporates. These are the world’s first RNA molecules, the predecessors to DNA. When the pond refills, the primitive genetic material becomes encapsulated by fatty acids to form microscopic soap bubbles—the first cell membranes.2

It doesn’t take long, a week perhaps, before the shallow ponds are covered with a yellow froth of trillions of tiny precursor cells filled with short strands of nucleic acids, which today we call genes.

Most of the protocells are recycled, but some survive and begin to evolve primitive metabolic pathways, until finally the RNA begins to copy itself. That point marks the origin of life. Now that life has formed—as fatty-acid soap bubbles filled with genetic material—they begin to compete for dominance. There simply aren’t enough resources to go around. May the best scum win.

Day in and day out, the microscopic, fragile life-forms begin to evolve into more advanced forms, spreading into rivers and lakes.

Along comes a new threat: a prolonged dry season. The level of the scum-covered lakes has dropped by a few feet during the dry season, but the lakes have always filled up again as the rains returned. But this year, thanks to unusually intense volcanic activity on the other side of the planet, the annual rains don’t fall as they usually do and the clouds pass on by. The lakes dry up completely.

What remains is a thick, yellow crust covering the lake beds. It is an ecosystem defined not by the annual waxing and waning of the waters but by a brutal struggle for survival. And more than that: it is a fight for the future—because the organisms that survive will be the progenitors of every living thing to come: archaea, bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals.

Within this dying mass of cells, each scrapping for and scraping by on the merest minimums of nutrients and moisture, each one doing whatever it can to answer the primal call to reproduce, there is a unique species. Let’s call it Magna superstes. That’s Latin for “great survivor.”

It does not look very different from the other organisms of the day, but M. superstes has a distinct advantage: it has evolved a genetic survival mechanism.

There will be far more complicated evolutionary steps in the eons to come, changes so extreme that entire branches of life will emerge. These changes—the products of mutations, insertions, gene rearrangements, and the horizontal transfer of genes from one species to another—will create organisms with bilateral symmetry, stereoscopic vision, and even consciousness.

By comparison, this early evolutionary step looks, at first, to be rather simple. It is a circuit. A gene circuit.

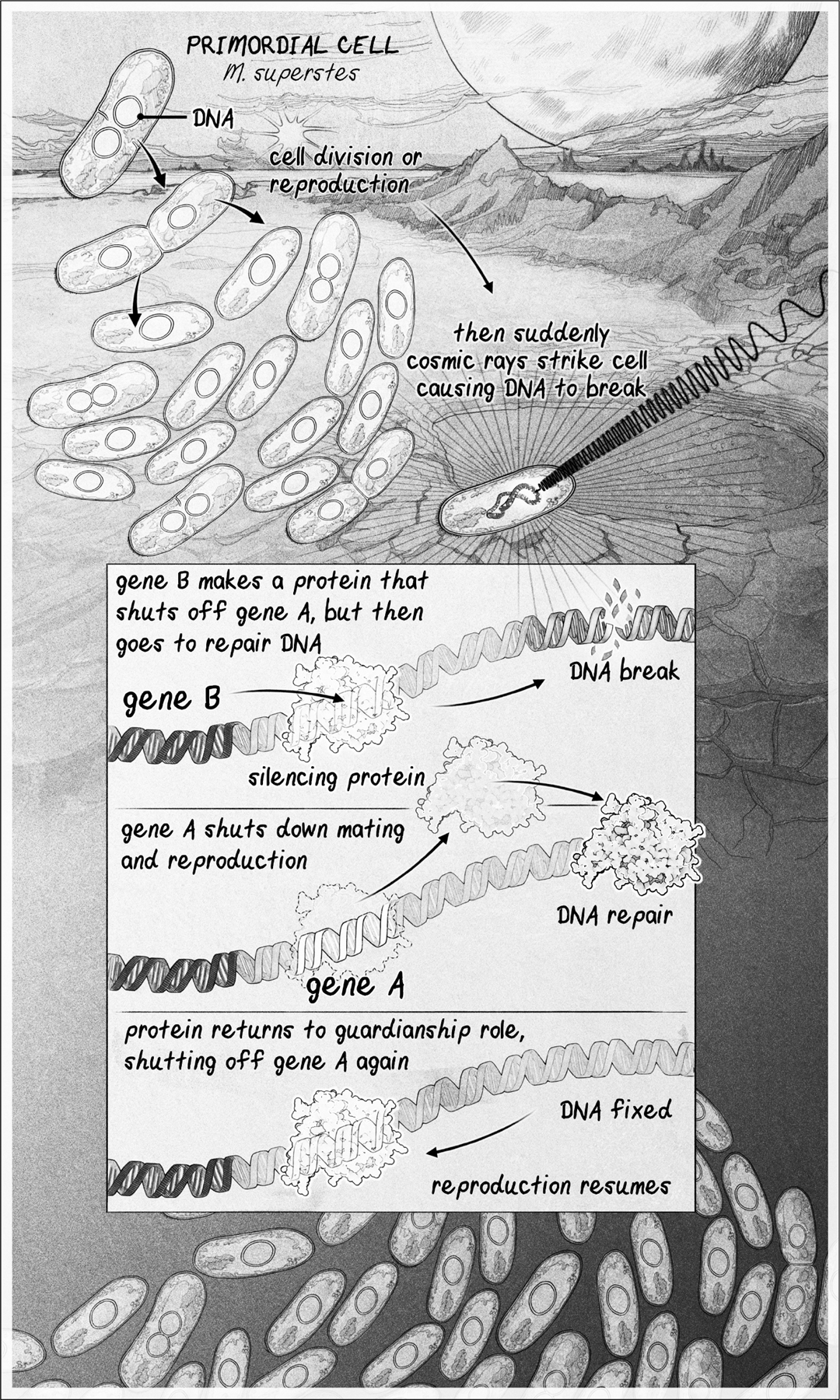

The circuit begins with gene A, a caretaker that stops cells from reproducing when times are tough. This is key, because on early planet Earth, most times are tough. The circuit also has a gene B, which encodes for a “silencing” protein. This silencing protein shuts gene A off when times are good, so the cell can make copies of itself when, and only when, it and its offspring will likely survive.

The genes themselves aren’t novel. All life in the lake has these two genes. But what makes M. superstes unique is that the gene B silencer has mutated to give it a second function: it helps repair DNA. When the cell’s DNA breaks, the silencing protein encoded by gene B moves from gene A to help with DNA repair, which turns on gene A. This temporarily stops all sex and reproduction until the DNA repair is complete.

This makes sense, because while DNA is broken, sex and reproduction are the last things an organism should be doing. In future multicellular organisms, for instance, cells that fail to pause while fixing a DNA break will almost certainly lose genetic material. This is because DNA is pulled apart prior to cell division from only one attachment site on the DNA, dragging the rest of the DNA with it. If DNA is broken, part of a chromosome will be lost or duplicated. The cells will likely die or multiply uncontrollably into a tumor.

With a new type of gene silencer that repairs DNA, too, M. superstes has an edge. It hunkers down when its DNA is damaged, then revives. It is superprimed for survival.

THE EVOLUTION OF AGING. A 4-billion-year-old gene circuit in the first life-forms would have turned off reproduction while DNA was being repaired, providing a survival advantage. Gene A turns off reproduction, and gene B makes a protein that turns off gene A when it is safe to reproduce. When DNA breaks, however, the protein made by gene B leaves to go repair DNA. As a result, gene A is turned on to halt reproduction until repair is complete. We have inherited an advanced version of this survival circuit.

And that’s good, because now comes yet another assault on life. Powerful cosmic rays from a distant solar eruption are bathing the Earth, shredding the DNA of all the microbes in the dying lakes. The vast majority of them carry on dividing as if nothing has happened, unaware that their genomes have been broken and that reproducing will kill them. Unequal amounts of DNA are shared between mother and daughter cells, causing both to malfunction. Ultimately, the endeavor is hopeless. The cells all die, and nothing is left.

Nothing, that is, but M. superstes. For as the rays wreak their havoc, M. superstes does something unusual: thanks to the movement of protein B away from gene A to help repair the DNA breaks, gene A switches on and the cells stop almost everything else they are doing, turning their limited energy toward fixing the DNA that has been broken. By virtue of its defiance of the ancient imperative to reproduce, M. superstes has survived.

When the latest dry period ends and the lakes refill, M. superstes wakes up. Now it can reproduce. Again and again it does so. Multiplying. Moving into new biomes. Evolving. Creating generations upon generations of new descendants.

They are our Adam and Eve.

Like Adam and Eve, we don’t know if M. superstes ever existed. But my research over the past twenty-five years suggests that every living thing we see around us today is a product of this great survivor, or at least a primitive organism very much like it. The fossil record in our genes goes a long way to proving that every living thing that shares this planet with us still carries this ancient genetic survival circuit, in more or less the same basic form. It is there in every plant. It is there in every fungus. It is there in every animal.

It is there in us.

I propose the reason this gene circuit is conserved is that it is a rather simple and elegant solution to the challenges of a sometimes brutish and sometimes bounteous world that better ensures the survival of the organisms that carry it. It is, in essence, a primordial survival kit that diverts energy to the area of greatest need, fixing what exists in times when the stresses of the world are conspiring to wreak havoc on the genome, while permitting reproduction only when more favorable times prevail.

And it is so simple and so robust that not only did it ensure life’s continued existence on the planet, it ensured that Earth’s chemical survival circuit was passed on from parent to offspring, mutating and steadily improving, helping life continue for billions of years, no matter what the cosmos brought, and in many cases allowing individuals’ lives to continue for far longer than they actually needed to.

The human body, though far from perfect and still evolving, carries an advanced version of the survival circuit that allows it to last for decades past the age of reproduction. While it is interesting to speculate why our long lifespans first evolved—the need for grandparents to educate the tribe is one appealing theory—given the chaos that exists at the molecular scale, it’s a wonder we survive thirty seconds, let alone make it to our reproductive years, let alone reach 80 more often than not.

But we do. Marvelously we do. Miraculously we do. For we are the progeny of a very long lineage of great survivors. Ergo, we are great survivors.

But there is a trade-off. For this circuit within us, the descendant of a series of mutations in our most distant ancestors, is also the reason we age.

And yes, that definite singular article is correct: it is the reason.

TO EVERYTHING THERE IS A REASON

If you are taken aback by the notion that there is a singular cause of aging, you are not alone. If you haven’t given any thought at all as to why we age, that’s perfectly normal, too. A lot of biologists haven’t given it much thought, either. Even gerontologists, doctors who specialize in aging, often don’t ask why we age—they simply seek to treat the consequences.

This isn’t a myopia specific to aging. As recently as the late 1960s, for example, the fight against cancer was a fight against its symptoms. There was no unified explanation for why cancer happens, so doctors removed tumors as best they could and spent a lot of time telling patients to get their affairs in order. Cancer was “just the way it goes,” because that’s what we say when we can’t explain something.

Then, in the 1970s, genes that cause cancer when mutated were discovered by the molecular biologists Peter Vogt and Peter Duesberg. These so-called oncogenes shifted the entire paradigm of cancer research. Pharmaceutical developers now had targets to go after: the tumor-inducing proteins encoded by genes, such as BRAF, HER2, and BCR-ABL. By inventing chemicals that specifically block the tumor-promoting proteins, we could finally begin to move away from using radiation and toxic chemotherapeutic agents to attack cancers at their genetic source, while leaving normal cells untouched. We certainly haven’t cured all types of cancer in the decades since then, but we no longer believe it’s impossible to do so.

Indeed, among an increasing number of cancer researchers, optimism abounds. And that hopefulness was at the heart of what was arguably the most memorable part of President Barack Obama’s final State of the Union address in 2016.

“For the loved ones we’ve all lost, for the family we can still save, let’s make America the country that cures cancer once and for all,” Obama said as he stood in the House of Representatives chamber and called for a “cancer moon shot.” When he placed then Vice President Joe Biden—whose son Beau had died of brain cancer a year earlier—in charge of the effort, even some of the Democrats’ staunch political enemies had trouble holding back the tears.

In the days and weeks that followed, many cancer experts noted that it would take far more than the year remaining to the Obama-Biden administration to end cancer. Very few of those experts, however, said it absolutely couldn’t be done. And that’s because, in the span of just a few decades, we had completely changed the way we think about cancer. We no longer submit ourselves to its inevitability as part of the human condition.

One of the most promising breakthroughs in the past decade has been immune checkpoint therapy, or simply “immunotherapy.” Immune T-cells continually patrol our body, looking for rogue cells to identify and kill before they can multiply into a tumor. If it weren’t for T-cells, we’d all develop cancer in our twenties. But rogue cancer cells evolve ways to fool cancer-detecting T-cells so they can go on happily multiplying. The latest and most effective immunotherapies bind to proteins on the cancer cells’ surface. It is the equivalent of taking the invisible cloak off cancer cells so T-cells can recognize and kill them. Although fewer than 10 percent of all cancer patients currently benefit from immunotherapy, that number should increase thanks to the hundreds of trials currently in progress.

We continue to rail against a disease we once accepted as fate, pouring billions of dollars into research each year, and the effort is paying off. Survival rates for once lethal cancers are increasing dramatically. Thanks to a combination of a BRAF inhibitor and immunotherapy, survival of melanoma brain metastases, one of the deadliest types of cancer, has increased by 91 percent since 2011. Between 1991 and 2016, overall deaths from cancer in the United States declined by 27 percent and continue to fall.3 That’s a victory measured in millions of lives.

Aging research today is at a similar stage as cancer research was in the 1960s. We have a robust understanding of what aging looks like and what it does to us and an emerging agreement about what causes it and what keeps it at bay. From the looks of it, aging is not going to be that hard to treat, far easier than curing cancer.

Up until the second half of the twentieth century, it was generally accepted that organisms grow old and die “for the good of the species”—an idea that dates back to Aristotle, if not further. This idea feels quite intuitive. It is the explanation proffered by most people at parties.4 But it is dead wrong. We do not die to make way for the next generation.

In the 1950s, the concept of “group selection” in evolution was going out of style, prompting three evolutionary biologists, J. B. S. Haldane, Peter B. Medawar, and George C. Williams, to propose some important ideas about why we age. When it comes to longevity, they agreed, individuals look out for themselves. Driven by their selfish genes, they press on and try to breed for as long and as fast as they can, so long as it doesn’t kill them. (In some cases, however, they press on too much, as my great-grandfather Miklós Vitéz, a Hungarian screenwriter, proved to his bride forty-five years his junior on their wedding night.)

If our genes don’t ever want to die, why don’t we live forever? The trio of biologists argued that we experience aging because the forces of natural selection required to build a robust body may be strong when we are 18 but decline rapidly once we hit 40 because by then we’ve likely replicated our selfish genes in sufficient measure to ensure their survival. Eventually, the forces of natural selection hit zero. The genes get to move on. We don’t.

Medawar, who had a penchant for verbiage, expounded on a nuanced theory called “antagonistic pleiotropy.” Put simply, it says genes that help us reproduce when we are young don’t just become less helpful as we age, they can actually come back to bite us when we are old.

Twenty years later, Thomas Kirkwood at Newcastle University framed the question of why we age in terms of an organism’s available resources. Known as the “Disposable Soma Hypothesis,” it is based on the fact that there are always limited resources available to species—energy, nutrients, water. They therefore evolve to a point that lies somewhere between two very different lifestyles: breed fast and die young, or breed slowly and maintain your soma, or body. Kirkwood reasoned that organisms can’t breed fast and maintain a robust, healthy body—there simply isn’t enough energy to do both. Stated another way, in the history of life, any line of creature with a mutation that caused it to live fast and attempt to die old soon ran out of resources and was thus deleted from the gene pool.

Kirkwood’s theory is best illustrated by fictitious but potentially real-life examples. Imagine you are a small rodent that is likely to be picked off by a bird of prey. Because of this, you’ll need to pass down your genetic material quickly, as did your parents and their parents before them. Gene combinations that would have provided a longer-lasting body were not enriched in your species because your ancestors likely didn’t escape predation for long (and you won’t, either).

Now consider instead that you are a bird of prey at the top of the food chain. Because of this, your genes—well, actually, your ancestors’ genes—benefited from building a robust, longer-lasting body that could breed for decades. But in return, they could afford to raise only a couple of fledglings a year.

Kirkwood’s hypothesis explains why a mouse lives 3 years while some birds can live to 100.5 It also quite elegantly explains why the American chameleon lizard, Anolis carolinensis, is evolving a longer lifespan as we speak, having found itself a few decades ago on remote Japanese islands without predators.6

These theories fit with observations and are generally accepted. Individuals don’t live forever because natural selection doesn’t select for immortality in a world where an existing body plan works perfectly well to pass along a body’s selfish genes. And because all species are resource limited, they have evolved to allocate the available energy either to reproduction or to longevity, but not to both. That was as true for M. superstes as it was and still is for all species that have ever lived on this planet.

All, that is, except one: Homo sapiens.

Having capitalized on its relatively large brain and a thriving civilization to overcome the unfortunate hand that evolution dealt it—weak limbs, sensitivity to cold, poor sense of smell, and eyes that see well only in daylight and in the visible spectrum—this highly unusual species continues to innovate. It has already provided itself with an abundance of food, nutrients, and water while reducing deaths from predation, exposure, infectious diseases, and warfare. These were all once limits to its evolving a longer lifespan. With them removed, a few million years of evolution might double its lifespan, bringing it closer to the lifespans of some other species at the top of their game. But it won’t have to wait that long, nowhere near that. Because this species is diligently working to invent medicines and technologies to give it the robustness of a much longer lived one, literally overcoming what evolution failed to provide.