Полная версия

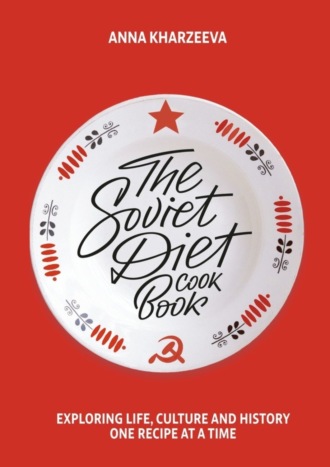

The Soviet Diet Cookbook: exploring life, culture and history – one recipe at a time

I may not mess about with the lay of the land any more, however. I’ll buy my rombabas from the shop and pour a Bacardi to go with it. Rum has very much made it to Russian parties and homes by now and has replaced Stalin’s preferred Georgian tipple. These days, “Dear Leader” would have to stay sober. Or maybe not, as the home of rum is none other than communist Cuba.

Recipe:

Dissolve yeast in 1 cup of warm milk. Add three cups of flour and knead into a stiff dough. Roll into a ball. Make 5 or 6 shallow cuts in the ball and place the dough into a pan filled with 2—2 ½ liters warm water. Cover with a lid and set in a warm place for 40—50 minutes.

For the cakes:

1 kg flour; 2 cups milk;

7 eggs; 1 ¼ cups sugar;

300 grams butter; ¾ tsp salt;

200 grams raisins; ½ tsp vanilla;

50 grams yeast.

For the sauce

½ cup sugar; 1 ¾ cups water;

4—6 spoonfuls of rum, wine or other liquor.

When the dough increases in volume by 50%, remove it from the water with a slotted spoon. Separate the eggs. Add egg yolks to sugar and mix until there is no white showing. Whip egg whites into a froth. Add to the dough ball the second cup of warm milk, salt, vanilla and egg yolks mixed with sugar. Mix well.

Add the remaining flour and knead the dough. After that, add the butter to the dough and knead very well. The dough should not be too thick. Again cover and put in a warm place. When the dough again increases in volume by 50 percent, add the raisins, stir and pour the batter into the prepared mold.

Cover and put in a warm place to rise. When the dough has risen to 3/4 the height of the molds, then gently, not shaking, put it in a cool oven, approximately 45—60 minutes.

During baking, the mold must be rotated with great caution, as even a slight push can cause the dough to fall. When the rombabas are ready, (readiness is determined in the same manner as in cakes). Remove from the mold and put on a dish. When cool, pour the syrup over them, carefully turning on a platter so they are soaked in the syrup soaked from all sides. Then, put them on a separate dish to dry. Put on another dish, covered with a paper towel, to serve

13. The breakfast all Russians love to hate. Mannaya kasha (semolina porridge)

This week, my breakfast meal was or semolina porridge, affectionately known as manka. This is the breakfast that Soviet people had every day, unlike the one described in the Book. mannaya kasha really

These days, however, I would never serve it for breakfast if I wanted people to speak to me again. Not that everyone hates it, but your chances of at least half the people in the room having a reaction of: “anything but this, I can’t believe this is happening to me” when served this meal are very high.

The reason for such a reaction is that manka has always been considered the best breakfast meal for kids, and it is served everywhere – at home, in preschool, at school, at the office cafeteria… It’s a milky gooey mass on a plate that, if not quite cooked right, or not very hot, turns quickly into… a milky gooey mass that is slightly less edible. It is a real life nightmare for many.

In a famous short story, “All Secrets Become Known,” a boy has to eat his manka or he won’t be allowed to go to the Kremlin. He hates the stuff and pours it out the window and straight on to someone’s hat. I still remember the drawing in the book with the porridge coming off a tall skinny man’s hat, nose and coat. I know many people who would say that’s exactly where it belongs.

Lucky for me, I actually like manka. Granny will make it for me on the odd occasion and I’m always happy to have it. I even ordered it at a restaurant recently! I loved watching people’s reaction when I told them what I ate. I think I narrowly avoided being put in a mental institution.

Even though I have manka every now and again, up to this point, I’ve been able to avoid making it for myself, as I know it’s not easy to keep it from forming lumps and/or burning. I was really focused and trying very hard, yet my porridge didn’t turn out perfectly – it was a little bit burnt, and had a few lumps in it. I ate it anyway.

Granny says she was surprised when in a kind of home economics class she conducted at school, a pupil was making manka with cold water. He put the dry manka in the proportion of 2 tablespoons per 1 cup water into cold water and then slowly brought it to a boil. He explained that this way there were fewer lumps. Granny took his advice to heart and makes manka that way to this day.

I also feel grateful to manka, since I recently found out it helped my parents survive. They were both born in 1963, a year in which, according to Granny, “ all the food suddenly disappeared from shops.” “There were no grains,” she said. “When your mom was little, I was surprised to find a packet of manka in the shop, and when I took it home, I saw that it had worms and bugs in it. Turned out it was the ‘strategic reserves’ that had been made a while ago and had gone bad.”

My dad’s mother says that when she was pregnant with my father and living in Kursk, she had even less food than there was in Moscow. She would be given some manka as well as some other foods at a special office for women who were pregnant or had young children, and that was a huge help.

It seems to me that unlike we young modern Russians, the Soviet adults stayed loyal to their childhood savior.

“There were carrot, cabbage and beet rissoles with manka for sale in the ‘gastronomy’ sections of restaurants and cafes,” Granny remembers. “They were all very popular.”

Granny’s friend Galina Vasileyvna also shared this story about the ubiquity of manka in the Soviet diet:

“When (bird’s milk) cake first appeared, it would be sold at the Praga Restaurant. It was so popular that you had to put in a pre-order and then wait your turn. Those who didn’t want to wait developed a recipe for it that could be made at home. In it, they replaced the soufflé with manka porridge. The recipe went around the whole country, traveling from city to city.” ‘ptichye moloko’

I will continue to stay loyal to the meal that kept me, my parents and grandparents full in the mornings – the porridge, not the cake. That would be my Soviet nightmare.

Recipe:

¾ cup milk; 3 teaspoons semolina; ½ teaspoon sugar; 1 teaspoon butter.

Add ¼ cup water to the milk and bring to a boil. When the liquid is boiling, slowly add the semolina, stirring constantly.

Add the sugar and a pinch of salt and cook on low heat 10—15 minutes. Put the butter on top of the porridge before serving.

Granny’s method:

2 heaped tablespoons semolina

1 cup milk or water, or half of each

Sugar to taste

Pinch of salt

Place the semolina into cold water in a pot, slowly bring to boil, add salt and sugar, reduce heat and stir constantly until it thickens up. Serve with jam.

14. Happy Soviet New Year’s eve. Olivier salad, biskvit

New Year’s Eve is a huge deal in Russia. It was made into the main holiday of the year during the Soviet era, since it wasn’t possible to celebrate a religious holiday like Christmas in an atheist state. As a result, New Year’s Eve is both an occasion to spend time with family and have a party with friends.

Most young Russians spend New Year’s Eve like this: From 9pm-midnight, you stuff yourself with the tastiest dishes your mother and grandmother can make. Then, as soon as you watch the broadcast of the president making his speech at 11:55, and hear the bells in the Kremlin tower strike 12, you’ll be out the door with three bottles of champagne up your sleeve. After a very civilized night out, you come home and collapse into bed at 5am, but don’t fall asleep until 9, since the fireworks go on until sun-up, which in midwinter is about 9am.

You spend the next three days finishing off everything that wasn’t eaten on Dec. 31. Good thing Russians get the first 10 days of January off from work!

New Year’s Eve dinner always includes Olivier salad; white bread with tiny canned fish known as shproty; an abundance of mandarins or oranges; the beet salad called vinaigrette; herring “under a fur coat” of carrots, potatoes, beets and onions; pickles; and a bottle or two of Soviet champagne. For dessert, in my family there would be “biskvit” – the only type of cake ever to be made in my family. Ever.

The best effort was always made for the most special night of the year, although the results of that effort depended on the era and financial ability.

“My mother said that growing up, I ate one orange,” Granny told me, remembering New Year’s Eves of her childhood. “She went to the Torgsin [a special store that accepted payment only in hard currency, not rubles] and exchanged a silver spoon for one orange.”

I ask here if that was a damn good orange – one worth family silver – but she can’t remember. I pretend I’m not upset and think of ordering a silver orange to use up my rubles before their value decreases further, given that this particular winter the ruble collapsed as a result of Western sanctions on Russia and the conflict in Ukraine.

As for vinaigrette, Granny remembers that when they lived “in evacuation” during World War II, her mother would make vinaigrette, and the people in the village they were evacuated to told her that they “had all the ingredients available, but they only serve this sort of food to pigs.”

The same villagers seemed keen to learn to make biskvit, though. During the war years, presents for soldiers at the front were collected in every town, and my great-grandmother made biskvit for the collection. Apparently everyone was very interested in the cake. At least according to the legend. I’ve noticed over time that most stories involving my great-grandmother feature everyone being stunned and amazed by the things she does!

I made the Soviet biskvit for a friend’s New Year’s Eve party, and it was a complete failure. I made it at my friend’s apartment and there was no mixer to use, so I whipped the dough by hand, which was clearly not enough. As a result, the cake turned out more like a flat omelette. I didn’t tell Granny, knowing she would just laugh, but I thought it would be a good chance to write her recipe down.

I was very surprised, shocked even, that the book didn’t have a recipe for Olivier salad, considering the outsized role it plays in the Russian diet. I would mock its presence at every New Year’s table, until the mocking turned into a tradition. I now must have it every year. In part it’s a joke, in part it’s just a really tasty salad. The past two years, I got my husband to barbeque some chicken to include in it, and made my own mayo, and, well, I’m salivating as I write this.

Olivier salad is one of the “noble” dishes, like beef stroganoff, vinaigrette or guryev porridge, that was Soviet-ized and put on every Soviet table with bologna substituting for the pre-revolutionary willow grouse meat. A quick search online shows a lot of theories, full of mystery and historical knowledge about Olivier and a lot of “I am right, you are wrong” comments that show Russians are still very passionate about this dish.

Trying to solve the mystery of Olivier, I started asking Granny questions.

“Did you always have Olivier?”

“We had vinaigrette and one other salad. We didn’t name the other salad anything.”

“So you had Olivier but didn’t call it that?”

“I don’t remember exactly when Olivier appeared, but everyone made salads to their own taste. The book you’re using, it’s from 1953, when there couldn’t be any foreign names. The salad must have become popular later.”

“But vinaigrette and beef stroganoff are not exactly Russian names.”

“They had long become Russian words by then. And, anyway, looking for logic in our country is laughable and useless.”

Whatever the explanation, Olivier salad will always have a place on my New Year’s table, along with biskvit, but Granny’s version – not the Soviet one!

Recipes:

Olivier salad:

4 medium carrots

4 eggs

6 medium potatoes

5—6 pickled cucumbers

1 can green peas

1.5 chicken breasts

2—3 Tbsp mayonnaise

Boil potatoes, carrots and chicken. Allow to cool. Cut up ingredients into cubes, add mayonnaise.

: biskvit

100 grams wheat flour;

100 grams potato flour;

1 cup sugar;

10 eggs;

¼ tsp vanilla

Separate the egg whites from the yolks. Put the whites in a cool place. Beat the egg yolks with the sugar until you can no longer see any white. You can add vanilla here. Then add the flour. Stir. Whip the egg whites into a solid foam. Mix them into the dough gently.

Pour the dough into a springform pan that has been lightly greased and floured. Fill the form ¾ full. Put in the oven at the average temperature for baking. Bake until the cake breaks free easily from the mold. Allow to cool on a wire rack.

Cut the cake in two (or into more pieces) and spread jam between the layers. The top of the cake can be covered with glaze and decorated with more jam, berries, candied fruit or nuts. Cut into thin slices with a sharp knife.

Granny’s biskvit:

5—6 eggs

1 cup sugar

1 cup mix of flour and cocoa or ground coffee

Mix 5 big or 6 small eggs with a cup of sugar using an electric mixer. Slowly add 1 cup of flour and cocoa, ground coffee or anything else you’d like to add. You can make half a batch with cocoa, and half plain and combine them in a baking mold. Bake for 45 minutes to an hour, first at 180C and then at 160. Leave until almost cool in the oven with a slightly open oven door.

15. The Caucasian answer to long winter nights. Bouzbash (lamb soup)

There are a lot of Soviet meals I’ve eaten but have never cooked, and there are a few Soviet meals I know well and have prepared, but this time I’m up against a meal I’ve not only never made or tried – I’ve barely even heard of it.

It’s bouzbash from the Caucasus country of Azerbaijan: lamb soup with apples, peas, potatoes and tomato sauce. Part of me wonders if perhaps there’s a good reason why I haven’t crossed paths with this Soviet delight. But another part of me has a lot of faith in the cuisine of the Caucasus, which is generally spicy and exciting.

The bouzbash turned out fine – not delicious, but edible – and it seemsto me that the recipe could be somewhat improved. I found a recipe online that suggests adding chickpeas instead of green peas and tomatoes instead of tomato puree. They sound like worthy adjustments.

One of the problems with the bouzbash, as with all lamb-based meals, is that it’s hard to get decent lamb in Moscow.

As for the other ingredients, they are easily available, except for uncooked peas. I was excited about going old school and boiling the peas, but was hit by reality: you can’t find uncooked peas anymore – they just come in cans.

It was a very different situation in the days when my grandmother was young: “During World War II, we kids would heat up the peas on a hot frying pan on an oven so they would get easier to chew. We would carry them around in our pockets and snack on them as if they were sunflower seeds or nuts. This was on top of lots of peas we were getting in soups and porridges, too. We had peas during the war, and nothing else,” Granny said.

Granny’s friend Valentina Mikhailovna also remembered that her mother knew a pre-Revolutionary recipe for pea kissel (a kind of drink) served with hemp oil. They also made rye pirogi with a filling of onions and peas.

As for lamb, in those days, you could find it at the kind of markets we would call a farmer’s market today. Granny called them “ an island of capitalism, where you could find almost anything and haggle over the price. You could also buy as much as you wanted, unlike in shops where there could be a ‘1 unit per person’ limit, like in the 1960s and 1970s, when food was in short supply.”

I’m glad I discovered this lamb meal, and, although we don’t have a huge amount of lamb to choose from, it will certainly go over well on a cold winter night, especially when everyone’s recovering from the New Year celebrations.

Recipe:

For 500 grams of lamb – one cup of split peas, 500 grams of potatoes, two apples, two onions, two tablespoons of tomato puree and butter.

Cut or chop up the washed lamb into 30-40-gram pieces. Place them into a pot, fill it with water so that the water covers the lamb, salt it and cover the pot with a lid. Simmer on a low heat, removing the froth.

In a separate pot, boil the washed and sorted out peas in 2—3 cups of cold water and simmer on a low heat. After about 1—1.5 hours, place the boiled pieces of lamb into the pot with the peas, removing the small bones.

Afterwards, add the strained broth, the finely chopped and fried onion, the sliced potatoes and apples, the tomato puree, salt, pepper and, covering the pot with a lid, stew for 20—25 minutes.

16. The tasty solution for leftover cottage cheese. Tvorozhniki/syrniki

This breakfast is dedicated to tvorog – a type of cottage cheese or curd that is very widely used in Russia. It is eaten for breakfast, used in desserts and stuffed into dumplings and pies.

Tvorog attracts a lot of respect in Russia. Being able to intelligently discuss the best ways of eating it, how to choose the best type and knowing how to prepare it will all get you a raise of the eyebrows and an approving nod of the head. Which is why I’m surprised that one of the most popular breakfast options made with tvorog is known as “syrniki” – literally, cheese things – as opposed to “tvorozhniki” – cottage-cheese things. I was pleased to find out that the Book calls them “tvorozhniki,” although it obviously didn’t catch on among the wider public.

Usually considered too good a product to be used in cooking, tvorog is often eaten by itself with sour cream and jam, so I suspect syrniki might have been invented as a means to use up tvorog that was already too old to be consumed uncooked. Nothing – let alone food – gets thrown out much in Russia. This cultural tendency definitely comes from the older generation who had to hold on to everything they had, whether it was old dairy products or candy wrappers.

Granny tells me that there was a joke in Soviet times referring to the “throwing out” of food – the verb used for “to throw out” and “to deliver to the shop in limited quantities to sell” was the same – vykinut’. In the joke, a foreigner and a Russian are standing by a store, and the Russian says: “look, they delivered some food!” to which the foreigner replies: “Yes, we throw out food of this sort, too.”

It seems like there was plenty of irony and general understanding that the way things were in the Soviet Union was far from perfect. For instance, all packaged foods had to have an official sticker known as a GOST sticker, which indicated that the food was made according to state standards. And the very best of each type of food would get an additional stamp shaped like a hexagon saying “znak kachestva” (assurance of quality). Factories would compete for this stamp, and considered it a big deal to have one of those on their cheese, tvorog, chocolate or tea.

The people, however, seemed far less excited about it. Among the general public, “znak kachestva” sarcastically became known as “we couldn’t do better if we tried.” I asked Granny if she would choose tvorog or other foods based on the hexagon stamp. She said she never did – she just bought whatever was available and affordable. If there was more than one type, then she’d choose by the region it came from. “Like now I choose dairy from New Zealand or France,” she said, before remembering about the ban on the import of many foreign foods that was issued in August 2014. “…Well, I did, when it was still there. Now I go for Belarusian products.”

I think I chose the wrong type of tvorog for my syrniki, as they turned out rubbery. he right type of cottage cheese should be quite wet and high in fat. My friend Vlad made some for me recently and he said about a pound of tvorog, 1 egg and 4 tablespoons flour is the right proportion. His tvorozhniki were perfect, so I’ll stick to his recipe from now on. See his recipe below. T

The challenge now is to resist the temptation to throw my tvorozhniki out and maybe find a way to re-cook them (something Granny would certainly do), and not to blame my poor choice on the absence of a hexagon stamp!

Recipe:

500 grams tvorog (cottage cheese);

½ cup sour cream; 1 egg;

2 tbsp butter; 2 tbsp sugar;

½ cup flour; ¼ tsp vanilla

Put the cottage cheese through a meat grinder or rub through a sieve. Add to a deep dish or pan. Put in ¼ cup sifted flour, sugar, salt, vanilla and egg. Mix well.

Put on a floured table and roll the mixture into a thick log.

Cut it crosswise into 10 equal-size cakes. Roll each cake in the remaining flour. Put into a heated pan coated with butter and fry on both sides until golden brown.

Top with powdered sugar, jam, or sour cream.

Vlad Bykhanov’s syrniki/tvorozhniki:

500gr cottage cheese

1 egg +1 egg yolk if the cottage cheese is dry

4 full tablespoons of flour + some more to cover in before frying

Salt and sugar to taste

6 teaspoons sour cream + more to serve

Form balls and roll them in flour, fry on an oiled pan on medium heat, turning frequently.

Turn heat off and top each syrnik with a teaspoon of sour cream and cover with a lid. The sour cream will make them more fluffy.

17. An expression of the Russian love for cabbage. Shchi

I think it’s no secret to anyone that Russians love our cabbage, although this is not necessarily by choice. I mean, it’s not like we had a nice spread of vegetables to choose from growing in the Russian soil. Many Russian dishes feature cabbage, and soup is no exception. Shchi, or cabbage soup, is probably the second most popular soup in Russia after borscht, although it is a lot less exciting.

I grew up with Granny’s shchi, which consisted of cabbage and broth, with the occasional addition of meat. She would serve it with some homemade croutons which, to be honest, were the most exciting part of it. I was a little bit surprised to read that the recipe in the Book also includes potatoes, tomatoes and carrots.

Just as well it did, too, because when I made it, I was visiting my Australian in-laws, and I didn’t think they would be terribly excited by the idea of having boiled cabbage and broth for dinner. The quality of produce in Australia is very high and as a result, the soup turned out nicely and was well received. At least my in-laws said they enjoyed it, and I’m just going to believe they were sincere.

I know foreigners have a limit on just how Russian they are willing to take with their meals. I wouldn’t try the layered mayonnaise and fish salad known as herring-under-a-fur-coat on the Australians because, well, they could just put me on the next flight home. When I cook for them, I have to pick the right meals and not overdo it on the “Russianness.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.