Полная версия

This was agreed to, and then Brangstrode summarized the position. ‘The matter stands then in this way. Unless everything is cleared up beforehand to our satisfaction, Alexander will represent us at the enquiry, taking Sutton with him. In the meantime we do nothing about any claim that may be made.’ He looked round on his little audience, and seeing approval on each face, turned to the solicitor. ‘And now, Alexander, what about that lunch I defrauded you of?’

With a little further talk the conference came to an end.

3

Sea Law

In due course the Barmore reached London and the shipwrecked crew came ashore. But whatever statement they may or may not have made to their owners, no further information was vouchsafed to Jeffrey. Instead he was simply informed that the Board of Trade enquiry into the disaster would be held on the following Wednesday in a court in Hopeney Street off Kingsway, under the presidency of Mr Courtney Trafford, a stipendiary magistrate with considerable experience of that class of work.

The newspapers, it was true, were full of the story. But their accounts were not very illuminating. As was to be expected, they wrote up the dramatic side of the tale for all they were worth, painting vivid pen pictures of an epic struggle to save a stricken ship amid a waste of tumbling waters in the darkness of the night. But over such dull matters as practical cause and effect they slid gently. Naturally perhaps, as the very mysteriousness of the happening was but so much more grist to their mill.

Jeffrey read these accounts with exasperated scepticism. He had not been content entirely to rest on his oars during that ten days before the enquiry. With some difficulty he had found out four insurance firms beside his own, which had covered portions of the cargo carried by the ill-fated ship. He had called in each instance on the manager and tactfully questioned him as to his views on the affair. In the case of three out of the four his efforts had met with a ready response.

These three managers admitted without hesitation that they viewed the circumstances with grave dissatisfaction. Mr Edwardes of the Derby & Yorkshire Company was the most outspoken.

‘Explosions?’ he had said. ‘What sort of explosions? They won’t say. They must surely know, that captain and crew. Then why all the mystery? I admit I don’t at all like the thing. I may say we’re not going to pay a penny till the whole matter is cleared up.’

‘So far as I can gather,’ Jeffrey answered, ‘Doulton of the Antwerp Company and Austin of the Narrow Seas take up the same position. And so do we.’

‘Of course you do. You’re attending the enquiry?’

‘Alexander, our solicitor, is watching it on our behalf, but I didn’t think of going myself.’

‘I shall,’ Edwardes returned. ‘If there’s going to be trouble, I want to know about it from the beginning.’

Jeffrey, remembering that this was the argument Alexander had used for taking Sutton, decided that after all he might as well attend himself. If the proceedings didn’t seem to be useful he could leave at any time. Besides, even if he were to wait till the end, it would not take up a serious amount of his time.

Jeffrey was more upset about the position of the Land and Sea than he would have cared to admit. Owing to various family troubles, he had never been able to save, and now at the age of fifty-two he was still entirely dependent on what he earned. He did not exactly fear that the payment of this £105,000 on the top of the £250,000 would cripple his company, but its prosperity was too intimately bound up with his own for him not to be profoundly anxious as to the outlook.

It was therefore with a direct personal interest in the proceedings that he presented himself with Alexander and Sutton at the Hopeney Street court at some twenty minutes past ten on the Wednesday morning following.

The room into which they presently pushed their way was of good size and was fitted with the usual court furniture. Bench, dock, jury box, witness box, well containing the solicitors’ table, and public galleries; all were arranged as in a criminal court—as indeed Jeffrey reminded himself this usually was. Unlike so many courtrooms, this was modern, airy and well lighted. In one other particular it looked different from the courts which Jeffrey had previously attended, and that was in the absence of policemen, of whom several had always been well in evidence.

But what most surprised Jeffrey was the number of people who were present. He had not expected the proceedings to be popular, but already there was a crowd of from eighty to a hundred standing chatting in little knots or seated as close as they could get to the central table. And nearly all of them looked as if they were there on business. There were a number of men whose black clothes, clean-shaven faces and thin compressed lips unmistakably suggested the law. Many more were obviously business men, and among them Jeffrey recognized several whom he knew. They were the managers of all four insurance companies on whom he had called, one or two other men interested in shipping, and Stewart Clayton, the manager of the Southern Ocean Company. There were men in blue suits and carrying bowler hats whom Jeffrey put down, correctly, as he afterwards discovered, as trades union secretaries. There was a rather woebegone cluster of men in poor clothes, obviously the shipwrecked crew, with, standing a little apart from them, but with a subtle suggestion of belonging to them, some half-dozen older and better dressed individuals, clearly the officers. Only a few persons who had taken seats in the public galleries appeared to be unconnected with the proceedings. These looked like unemployed, who had drifted in as a relief from the dreadful tedium of their lives. Not a single woman or girl was present: all were men.

‘This is going to be a bigger thing than I had any idea of,’ Jeffrey remarked to Alexander, as they squeezed their way into a seat near the solicitors’ table.

‘There are a good many interests affected,’ Alexander replied, ‘and probably most, if not all, are represented. There’s first of all the Board of Trade, then the owners, then the underwriters, then at least five insurance firms who covered the cargo. You discovered four besides your own firm, didn’t you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, they’re probably all here. Then the British Latin States people will be called in connection with the rescue of the crew. And that’s only one side of the affair. The captain, officers and crew of the lost vessel are in a way of speaking upon trial. They will be here both as witnesses and to see that they get a fair hearing.’

‘That lot over there, I should say.’

‘I imagine so. It’s rather a serious business for the senior officers. The court can reprimand them, or suspend or remove their certificates, in the event of negligence or other fault being proved. They can’t be sent to prison, but even a reprimand is a terribly serious thing for an officer, specially a master.’

‘You mean he’d lose his job?’

‘Almost certainly. And that wouldn’t be the worst of it. He’d probably never get another. Particularly now, when so many qualified men are unemployed.’

‘Means ruin for life?’

‘It does, and so I expect the chief officers are all legally represented. And that adds to the crowd.’

As he spoke, Clayton saw Jeffrey and pushed across. ‘Extraordinary affair this,’ he remarked. ‘Quite outside my previous experience.’

‘I’ve only heard what you told me yourself,’ Jeffrey answered, when he had introduced Alexander. ‘Has your captain not been able to clear it up?’

‘No, that’s just it,’ Clayton returned. ‘He doesn’t know a thing about it. His statement is simply that explosions occurred, but what caused them he can’t say. Extraordinarily unsatisfactory.’

‘Probably the enquiry will bring out the truth.’

‘I’m sure I hope so. Not to know is bad for us from every point of view. But you’re almost as much interested in it as we are?’

‘A good deal more deeply than we care to be,’ Jeffrey admitted.

Clayton shook his head. ‘Well, let’s hope for the best,’ he murmured, as he moved to a seat beside his solicitor.

It was now half-past ten, the hour at which the proceedings were to open. People had continued to pour in, till the room was practically full. Almost all had found seats. The shipwrecked crew, of whom there seemed between thirty and forty, had pushed into the jury box and the witnesses’ seats behind. Counsel with their formidable briefs, and their attendant solicitors with their reference books and stacks of papers, had taken their places at the table. There was still, however, movement all over the room and a loud buzz of conversation.

Presently there came a cry of ‘Silence!’ Everyone stood up and the stipendiary magistrate, Mr Courtney Trafford, entered, followed by two other men. He took his place in the centre of the dais, bowed to those present, and sat down, his companions sitting on his right and left hands respectively.

‘The assessors,’ Alexander whispered. ‘Technical men appointed to advise Trafford.’

Jeffrey nodded, settling himself more comfortably in his seat. They were punctual about beginning at all events. He hoped this was an augury for the speedy conduct of the case.

There ensued a number of rather uninteresting formalities, and then all sorts of people from all over the room, Alexander among them, got up and said they were appearing for this or that interest. Their names were duly noted, and a short discussion then took place between the magistrate and his assessors. When this was over, Mr Trafford made a brief opening statement.

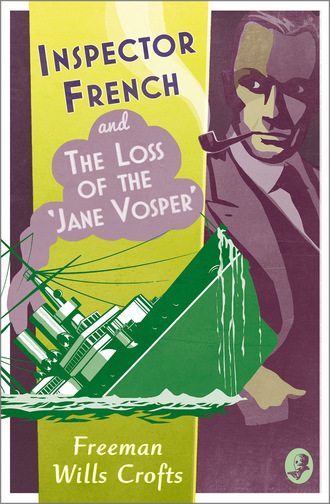

‘As you are aware, gentlemen, this enquiry is into the circumstances of the sinking of the steamer Jane Vosper, while on a voyage from London to Pernambuco and other ports in South America. The court will be concerned in the first place with the fact and the cause of the sinking, but it will also take cognizance of the conduct of all those concerned, inasmuch as this may have contributed or otherwise to the sinking. This will include not only the actions of those on board the ship, both before and at the time of the disaster, but also those whose duty it was to see that she went to sea in a reasonably fit and perfect condition, both as regards the ship herself, the appliances and stores which she carried, and the nature and disposal of the cargo.

‘The loss of a ship at sea is always a distressing event to all concerned, and this case is no exception to the rule. At the same time it is a matter of congratulation that in this instance the worst feature of such disasters is missing—there was happily no loss of life. That fortunate circumstance will not, however, make any difference to the course of this enquiry, particularly as we have only to remember that had the weather been different, it is possible that not a single member of the crew would have escaped.

‘I shall now ask you, Mr Armitage, to open the proceedings on behalf of the Board of Trade.’

Mr Reginald Armitage, one of the barristers present, was a tall man with an impressive carriage and a dominating manner. His hawk-like face and heavy jaw bespoke a tenacity of purpose which would not easily be turned aside from the path he wished to follow. His very look of conscious power and grip was a reassurance to those for whom he appeared, and induced doubts of their case into the minds of his opponents. And when he spoke, these feelings became strengthened. He had a full rich voice with which he could make great play, modifying it, as it were between the aggressive roaring of the lion and the seductive softness of the sucking dove. It was rumoured by those who did not like him, that in civil cases he made huge sums merely by not being on the other side.

‘Your Worship,’ he began quietly, standing up and turning towards the magistrate, ‘after what you have just said there is no need for me to waste the time of the court with prolonged remarks, and I will be very brief.’

He paused and hitched his gown up on his shoulder, a characteristic action. Then in a louder and more assured tone he went on:

‘As Your Worship has pointed out, this enquiry is into the sinking of the steamer Jane Vosper on the morning of Saturday, 28th of last month, while she was on a voyage from London to Pernambuco in Brazil.

‘The Jane Vosper, as you will hear in evidence, was a cargo liner of some 2500 tons register, owned by the Southern Ocean Steam Navigation Company of Fenchurch Street, and registered in London. Her length was 270 feet, beam 36 feet, and draught 16 feet. She was built in 1913 for the general carrying trade, and carried a complement of 35 officers and men.’

Mr Armitage then went on to describe the vessel, with its high fo’c’sle, bridge-deck and poop and the comparatively low stretches of well-deck between. He told of the location of the stores and of the berthing of the officers and crew. He referred briefly to the engines and boilers and went into detail about the size and position of the three holds and the number and position of the watertight bulkheads dividing them. When he had finished there was not much about the vessel that he had not covered.

‘As to the actual voyage and to the extraordinary series of explosions as a result of which the ship sank,’ Mr Armitage went on, ‘I propose to say very little, as I think you will get a better idea of these direct from Captain Hassell, her master, who is with us today. But very broadly speaking,’ and Mr Armitage went on to describe both, not indeed broadly, but in the utmost detail. He told the story vividly and well, from the loading of the cargo in the London Docks right up to the point at which the Barmore picked the crew up from the boats. Nothing was omitted from the tale, except the explanation of what had really occurred. Mr Armitage didn’t say in so many words that this was a mystery, but indicated that all the available evidence on the point would be put before the court. Then after a short peroration on the importance of the case and the number of interests involved, he sat down.

But immediately he was on his feet again. ‘James Hassell,’ he called, glancing over the assembly.

Captain Hassell, looking anxious and thoroughly woebegone, rose from his seat with the other officers and moved round the room to the witness box. There he was sworn and invited to sit down.

‘You are James Hassell, master of the Jane Vosper, the ship which is the subject of this enquiry?’

‘I am.’

Then ensued a long questionnaire on Hassell’s age, qualifications and career. He had been twenty-five years with the Southern Ocean Company, eighteen as a skipper, and eight in command of the Jane Vosper. He was adequately qualified for his job and had never before been involved in any serious mishap.

A similar but more detailed questionnaire on the ship herself followed. Her size, age, design, workmanship and equipment were taken in turn and legally established. The captain said she was a good sea boat, steady, easy to steer, and very dry, as well as being well built and well found in every way. There was nothing about her, he declared, to account for the explosions or to warrant any suggestion that she had been sunk more easily than a ship should.

Mr Armitage then turned to the voyage and took Hassell through each step from the London Docks until the first explosion.

‘Now,’ he went on, ‘during those six days of the passage, up till the time of the first explosion, did you notice anything abnormal or unusual about the ship or crew?’

‘Nothing whatever. Except for the delays from fog and wind, the voyage was entirely normal and satisfactory.’

‘You were satisfied with your crew?’

‘Absolutely.’

‘There was nothing to suggest that disaster might be approaching?’

‘No, sir. Nothing.’

‘Except that you had lost some thirty-three hours, you were entirely satisfied with your progress?’

‘Entirely.’

‘And before you started? Was everything perfectly normal and satisfactory?’

‘Perfectly so.’

‘Were you satisfied with the nature and stowing of the cargo?’

‘Quite satisfied.’

‘Very well. Now we come to the explosions. Will you tell us in your own words what occurred?’

Hassell told of his being unable to sleep and his decision to go on deck, of his doing so, of the sea that was running, and of the first explosion. Then he described the steps he had taken to ascertain the damage. How he had rung down the engines to SLOW AHEAD, reducing the speed as much as possible consistent with keeping the ship’s head to the seas. How he had called for information to the engine-room and taken over the ship himself, so that his deck officers might go and find out what had happened.

Slowly Mr Armitage took him through the events of that dreadful night. The second explosion, the third, the fourth. The orders he had given, the wireless messages he had sent, his inspection of the damage in the stokehold and No. 1 hold, and his consultations with the chief engineer and first officer. Finally, his conclusion that the ship could not be saved, the last message to the approaching Barmore, and taking to the boats, the sinking of the Jane Vosper, and the final rescue by the Barmore.

The K.C. then turned once again to the explosions.

‘Now at first you tell me you weren’t certain of exactly where the explosions had occurred. But later you came to a conclusion on this point?’

‘In the light of what happened afterwards, it was clear that they were in No. 2 hold.’

‘Quite. What size was this hold?’

‘About 40 feet long by the full breadth of the ship, say 34 feet, and about 17 feet deep.’

‘That’s a large space, very much the size of this room, I should say.’ Mr Armitage looked round. ‘Now can you form any opinion as to whereabouts in the hold the explosions occurred?’

For the first time Captain Hassell looked doubtful. ‘I’ve been thinking about that, sir,’ he answered. ‘While I can’t swear to it, I am of the opinion that they were low down.’

‘Yes? Why do you think so?’

Again Hassell hesitated. ‘I’m afraid it’s more what the chief engineer reported than what I saw for myself,’ he admitted. ‘He said—’

‘Well, we’ll get that from him. What did you see for yourself?’

‘When I went down to the stokehold after the last explosion I saw that the principal buckling in the bulkhead, what I might call the centre of the buckling, was low down: about five feet from the floor plates. That’s what I saw, but there was another reason. It didn’t occur to me at the time, but I’ve thought of it since. It seemed to me the shots were individually small. If they hadn’t been, they would have blown the hatches off. But if they were small, they must have been low against the ship’s bottom to puncture her plates.’

‘Yes?’

‘I think, sir, that without considering the puncturing of the ship’s bottom at all, one could say they were low down because they didn’t raise the hatches.’

‘I should have thought that even a small explosion and low down would have blown off the hatches. Would a large volume of gas not have been generated, which must have gone somewhere?’

‘That is so, but in the case of the Jane Vosper the holds were well ventilated and in my opinion the ventilators afforded the necessary relief.’

‘Ah, quite so. That all sounds very clear and very ingenious, if I may say so, captain. An interesting and important point, that the charges were probably small.’ He paused for a moment, then resumed. ‘Now another point. Was any adjustment made with the disposition or otherwise of the cargo since the stevedores finished with it?’

‘No, sir, the hatches weren’t opened.’

‘But you have told us that the holds could be entered without opening the hatches?’

‘That is so. But the cargo would not normally be moved without opening the hatches.’

‘I see. Do you mean then that at the time of the explosion the hold contained everything loaded by the stevedores and nothing else?’

‘I believe that to be correct.’

‘What’s your own view, captain, as to the cause of the explosions?’

‘I can’t explain them at all. I know of nothing that could have caused them and am entirely puzzled by the whole thing.’

‘Now, here’s a more difficult question. During the loading of that hold, up till the time the hatches were battened down, could anyone have placed explosives in the hold?’

A slight movement passed through the assembly. This was the first time the suggestion of foul play had crept into question or answer, and it evoked a corresponding reaction. Persons who were already looking bored sat up sharply. The atmosphere grew more tense.

But the suggestion did not seem strange to Captain Hassell. He agreed that this was a more difficult question. He didn’t think anything of the kind could have been done, though he wasn’t prepared to state it as a fact. In the daytime he believed it would be impossible. He pointed to the fact that during loading hours no one could have approached unseen. At night there was a watchman aboard, apart from those on the wharves, and he thought it very unlikely that anyone could have passed these men.

‘Then with regard to the period between the battening down of the hatches and the disaster. During that period could anyone have smuggled in explosives?’

As to the possibility of this the witness was not so sure. Granted that someone with explosives was on board who wished to sink the ship and endanger his own life, Hassell supposed an opportunity could have been found. But he was dogmatic about its probability. He didn’t believe that any of the men who were on board were capable of doing such a thing, or had done it.

Mr Armitage did not press the point, but turned instead to the question of the wireless signals. These he went over in detail, obtaining Hassell’s reason for every message he had sent. He was particularly searching in his questions with reference to the final S O S, and the reason which induced the captain to abandon ship. At the end he said, ‘Thank you, captain,’ and sat down.

As he did so another little wave of movement passed over the room. People who had been listening intently suddenly found they had become cramped, and took advantage of the break to change their positions. A buzz of conversation arose, as whispered remarks were exchanged. Then Mr Trafford’s voice was heard inviting anyone who was appearing for a client, and who wished to ask questions, to do so.

Three or four of the legal-looking men stood up, and Trafford took them in turn. But to Jeffrey their questions seemed to have very little point. In no case did they succeed in bringing out anything new. All that they got was confirmation of statements already made.

When the last had finished Trafford said he would himself like to ask one question: ‘When your second officer reported that there was fire in No. 2 hold, what exactly did you do? I ask because no action seems to have been taken to deal with it.’

‘I realized the danger of fire at once, sir,’ Hassell replied, ‘and I was quite clear as to what I should do about it. But I was more afraid that the ship might be taking water, and until the wells were sounded, I refrained from any decision as to the best thing to be done. In the end the fire was put out automatically by the flooding of the hold.’

Trafford nodded. ‘I follow,’ he admitted, then went on: ‘That will do for the present, Captain Hassell. Please don’t go away, as some further question may arise. Now, Mr Armitage?’

Hassell left the box and Armitage stood up and called, ‘Henry Arlow.’

Arlow was sworn, and then in due form asked his name, position, qualifications and history. Though he was only first officer of the Jane Vosper and had never had a ship, he had held for eight years his master’s certificate. His qualifications were therefore satisfactory and his record was good.

Then to Jeffrey and others of those present the enquiry began to drag. For all the preliminary questions asked Arlow were those which the captain had already answered. It was not until Armitage reached the actual explosions, that Arlow had anything new to tell.