Полная версия

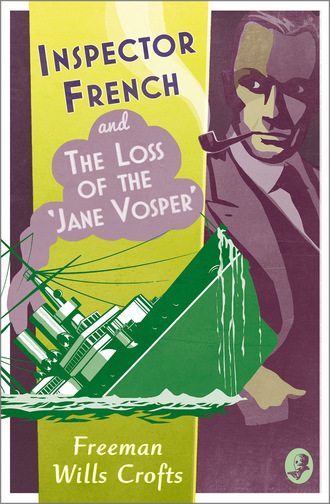

He turned back to the wheel-house. ‘Lash that wheel, Simmonds,’ he said to the helmsman, ‘and get away to the boats. Blair, get away.’

‘Aren’t you coming, sir?’ Blair asked.

‘Yes, I’m coming. Get a move on with those boats. She won’t last much longer.’

Blair and the helmsman ran down the ladder. The boats were lowered. First the port and then the starboard reached the water, the falls were unhooked, quickly, skilfully. The men began to climb down. In a couple of minutes the port boat had her complement and had pushed off from the swaying side. Then Hassell saw the starboard boat was also filled. With a last glance forward over the bows he had looked out over for so many years, Hassell walked, still slowly and with dignity, down the bridge ladder and climbed into the boat.

The Jane Vosper was still forging slowly ahead, and the men, as soon as they had pulled far enough away from her to be safe from her suckage, turned with one consent and began rowing with her, determined to see the end. In silence they watched her, plunging a little deeper into each swell, recovering a little more slowly, the stern rising a little higher … Not a man but was heartily thankful to be out of her, and yet she was their home. All but a few of their possessions, such as they were, were aboard. In the case of the captain his hopes were aboard too.

For ten minutes they watched, then a cry broke out. She was going! At a distance of perhaps quarter of a mile they saw her stern slowly rise. It went up and up and up, with the screw racing, while her bow up to her bridge disappeared beneath the water. The stern hung poised—for hours, it seemed. Then very slowly it began to go down, more and more quickly, till at last it disappeared behind a smooth rolling swell.

Alone on the sea, the boats instinctively drew together.

2

Sea Risk

In a private room in a suite of offices on the fourth floor of a large building in Mincing Lane three men sat talking.

The building was new. It was the last word in office design, with roomy landings and corridors, decorated with simple though slightly startling designs and lighted from unexpected places by glowing tubes. The floors were of rubber, coloured in the shapes conventionally assigned to lightning, though admittedly lightning in rather solid flashes. The four lifts had grilles of bronze, and fascinating little lights popped in and out as the cages rose and fell.

The fourth floor housed a firm whose plate read ‘The Land & Sea Insurance Co., Ltd.’ with below it the word ‘Enquiries’ and the representation of a hand pointing towards three o’clock.

The office in which the three men sat talking was at the end of the main corridor. It was the private room of the manager, Arnold Jeffrey, and he was discussing business with Wallace Crewe, his accountant, and Wilfred Leatherhead, his chief clerk.

For a private office, the room was large and ornate, providing ocular demonstration to the caller of the stability and prosperity of the company. It contained a large flat-topped desk, at which Mr Jeffrey was now seated, and two leather-covered arm-chairs, containing respectively his two assistants. All this furniture rested on a very thick, brightly-coloured carpet, which also bore a table with glass top and curved steel legs, a file case, a waste paper basket, and a nest of sectional bookcases, mostly containing books on law and insurance.

Jeffrey was a big man of about fifty, with a heavy jaw, thin, closely compressed lips, wide awake eyes, and a slightly unpleasant expression. He was an able manager, and if he was not greatly liked in a personal capacity he was respected as a sound business man and an efficient chief.

Crewe and Leatherhead, except that one was tall and thin and the other small and stout, were alike in that they were typical heads of departments in a business of the kind. Both were good men—if they weren’t they wouldn’t have remained long under Jeffrey’s management, but neither was outstanding, and for the same reason.

They were discussing a message which had been received a short time previously from the Weaver Bannister Engineering Company Limited, of Watford, a firm with whom they had recently done business. That their information was serious was evident from the expression of all three. Indeed they looked as if they had just received the news of a disaster.

‘A hundred and five thousand, wasn’t it?’ Jeffrey was saying, and there was something approaching horror in his tones.

‘Yes,’ answered the chief clerk with equal emotion, glancing at a paper he held. ‘There were 350 sets and they were covered at £300 apiece: makes £105,000.’

For a moment there was silence, a brooding silence, and then Jeffrey spoke again with vicious emphasis. ‘Damned ill luck its coming just now,’ he declared. ‘We were badly enough hit by that Chelsea fire, and to have to pay out another hundred thousand on the top of that, as well as having had a bad year generally, is something that won’t bear thinking about.’

‘It’s very unfortunate,’ Crewe answered somewhat inadequately, while Leatherhead murmured agreement.

‘I’ve rung up the chairman,’ went on Jeffrey. ‘I did it first thing when I got the message. He said he’d come across at once.’

‘He’ll be pretty badly hit,’ the accountant considered. ‘Last time he was speaking to me he wasn’t too happy about our position. This’ll about put the lid on it.’

‘Yes, he was talking to me, too,’ Leatherhead added. ‘He was worried about the dividend. Said there never had been such a year of losses since the company was formed.’

‘I don’t know how we’re going to meet another hundred thousand without something unpleasant happening, and that’s a fact,’ Jeffrey declared unhappily, and was going on to develop his theme when there was a knock at one of the two doors and a pretty girl looked in. ‘Mr Brangstrode’s here, Mr Jeffrey,’ she said.

‘Show him in,’ Jeffrey answered, while the other two got up from their chairs.

The young woman stood back and a tall man with aquiline features and greying hair entered the room. There was a suggestion of power in his strong chin and quiet though forceful movements. He was just sixty and looked ten years younger.

Rupert Brangstrode had been chairman of the Land and Sea for the past six years, though it was small beer to him, most of his energies having been put into larger corporations with which he was also connected. However, under the combined management of himself and Jeffrey, the Land and Sea had considerably increased its business. A prosperous business, too, it had been, at least up to the present year. Within recent months bad luck had seemed to dog it. There had been burglaries and accidents which had proved heavy losses, culminating in a fire in Chelsea in which valuable old pictures, insured with the company for the sum of £250,000, had been totally destroyed. The dividend prospects for the current period were therefore distinctly unpromising.

Brangstrode having nodded to the three men, laid his hat on the glass table and sat down in one of the armchairs.

‘What’s all this, Jeffrey?’ he asked in the words of a policeman investigating a street row.

‘More trouble, I’m afraid,’ the manager answered with a worried air. ‘About an hour ago I had a telephone from Bannister’s people of Watford, saying that they had heard that the steamer carrying their consignment of petrol sets to South America had been totally lost.’

The chairman moved impatiently. ‘So you said. I remember we accepted the policy, but except that they were large, I’ve forgotten the figures.’

‘Yes, sir, they were large,’ Jeffrey agreed gravely. ‘There were 350 sets and each was covered at £300. The total cover was £105,000.’

Brangstrode’s face fell. ‘£105,000! Good God!’ For a moment there was silence and then he went on: ‘Well, is it true, this report?’

‘Directly I received it I rang up the shipping company, the Southern Ocean Steam Navigation Company of Fenchurch Street, and asked them. They said it appeared to be true. They had had a cable via Madeira from the skipper of their steamer Jane Vosper, the ship in question, saying that there had been some unexplained explosions aboard, and that part of the ship was flooded. The message said that there was no immediate danger and that they hoped to make Funchal under their own steam. That, the Southern Ocean people said, was the only information they had received direct from the ship.

‘But later they had had a message from the British Latin States people in Gracechurch Street to say that the master of their ship, the Barmore, homeward bound from Buenos Aires, reported that he had just received an S O S from the Jane Vosper, which said that she was sinking rapidly and that they were abandoning ship. The master of the Barmore said the weather was good and that he expected to pick up the crew about midday, that is,’ Jeffrey glanced at the electric clock on the opposite wall, ‘just about an hour ago.’

‘Then it looks a true bill,’ Brangstrode considered.

Jeffrey shrugged. ‘I’m afraid so. The British Latin States people said they expected to hear from their captain if and when he picked up the men, and I asked Clayton to let me know immediately they rang him. We might hear any time.’

Brangstrode nodded, but for some moments remained silent. Then presently he went on: ‘If this turns out as you say, what becomes of our dividend?’

‘I was considering that when you came in,’ Jeffrey returned. ‘I think,’ and he drifted off into technicalities.

‘I suppose,’ said Brangstrode, when this point had been discussed, ‘there’s no chance of our not being liable? Explosions? That sounds like the engine-room? Steam pipes, or boilers, or perhaps a mechanical breakdown? If the accident were due to carelessness or improper management or inferior materials, could we make anything of that?’

Jeffrey shook his head. ‘I doubt it. I should think all those things would be included in the risks we insured against.’

‘What sort are these Southern Ocean people? Know anything about them?’

‘Oh, yes, I think they’re all right. They’ve got a good reputation in the City. A small firm, but quite sound and all that.’

‘Have they only tramps?’

‘As a matter of fact, their boats are liners, not tramps. I used to think all cargo boats were tramps, but they’re not.’

‘I always thought so myself.’

‘We were both wrong. It appears a liner is a ship which travels backwards and forwards on a regular schedule, as these boats do—between London and Buenos Aires. A tramp is a ship that makes no regular journeys: it will take cargo for anywhere hoping to pick up cargo at that port for somewhere else, and so on. Of course, a liner and a tramp may be structionally similar, and a ship may be a liner at one part of its career and a tramp at another.’

‘I didn’t know that. Well, tramps or liners, are they sound ships?’

‘I think so. The Southern Ocean has had very few accidents. Stewart Clayton’s their manager.’

Brangstrode made a gesture. ‘Clayton? I know him. A good man, I agree.’

‘The ships are reputed to be well built and well found. We made, of course, the usual enquiries about them when we learned they were taking the Bannister stuff. But we’ve come across them several times before. They’ve often carried stuff covered by us.’

‘A small firm, you say?’

‘Yes, as shipping companies go. They’ve got small boats, from two to four thousand tons register. I don’t know how many—not very many, I think. They run three services. London to Buenos Aires, calling at various South American ports; London to the West Indies, calling at several islands, and London to the Central American states, including Mexico.’

‘Freight only?’

‘Yes, they don’t take passengers.’

‘I happen to have met Captain Hassell of the Jane Vosper,’ observed Leatherhead suddenly. ‘I was at their offices on another job. You remember, sir, that railway stuff that we covered for Trinidad? While I was there Captain Hassell came in. Mr Clayton introduced us.’

‘And what did you think of him?’ Brangstrode asked.

‘He seemed to me a thorough good man, sir,’ the chief clerk answered with decision. ‘Of course you can’t be sure in one short interview. But I was very favourably impressed. Quiet and businesslike, he seemed, like a man who wouldn’t lose his head in an emergency.’

‘I wonder who insured the ship?’

Jeffrey shook his head. ‘I’ve no idea. They may be their own insurers for all I know to the contrary.’

‘Not very likely if they’re a small concern.’

‘That’s true. Lloyd’s, then, I expect. We can find out easily enough.’

‘It would be interesting to know.’

Once again the rather desultory conversation turned to their own possible loss. Then after some time Brangstrode raised another point.

‘We surely can’t be the only insurance firm interested? What space would these blessed sets take up?’

Jeffrey turned to the chief clerk. ‘You have the description of them somewhere?’

‘I have it here.’

Jeffrey glanced down the paper Leatherhead handed him, then read:

‘“Each set consists of one of our Exo petrol motors, connected direct with an Alilo dynamo, together with a separate switchboard. The sets are packed in strong wooden cases, measuring 2´ 0˝ by 2´ 0˝ by 4´ 0˝.” That would be,’ Jeffrey calculated quickly, ‘16 cubic feet per set, and 350 times 16—5600 cubic feet for the lot, or say, a block 20 feet wide, 28 feet long and 10 feet deep. It probably wouldn’t fill one of her holds.’

‘Then she must have been carrying a lot more stuff?’

‘Sure to have been,’ said Jeffrey.

‘That means that other insurance firms are also interested in the loss?’

Jeffrey agreed again.

‘Interesting to find out what other cargo there was and who had covered it,’ Brangstrode said thoughtfully.

Jeffrey’s reply was interrupted by his telephone bell. With a gesture of apology he picked up the receiver. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘Jeffrey speaking … Oh, they have? I’m glad to hear that … Yes … Yes … No further statement? … What do you think yourself? … On Thursday morning? … Shortly after that, I should think … Then you’ll let me know? Thank you, Clayton, very much.’

Jeffrey put down the receiver. ‘That was Clayton,’ he explained. ‘He says they’ve just had a phone from the Latin States people. A message has just come in from the captain of the Barmore, saying that he’s picked up the crew of the Jane Vosper. At half-past eleven he came in sight of them, and by twelve they were all on board. They reported that the Jane Vosper had gone down a few minutes after they abandoned her, about half-past eight this morning. They say that explosions in the hold damaged the hull, and that one watertight compartment was completely flooded and the two adjoining compartments were leaking more quickly than they could pump them out. They’re making no further statement till they reach home, which, it is expected, will be on Thursday morning. Clayton says the Board of Trade enquiry is certain to be held almost at once, and he’ll keep me advised of all that becomes known.’

‘Then she’s gone,’ Brangstrode concluded, ‘and it looks as if our £105,000 is gone with her.’

‘Clayton had no theory as to what might have happened?’ Crewe asked.

‘None whatever; or if he had, he didn’t mention it. No; he seemed as puzzled as I am.’

‘It definitely wasn’t a steam burst, or a mechanical breakdown?’ Crewe went on.

‘Clayton said “Explosions in the hold.” I should have thought if it had been a steam pipe or something like that, he’d have said so.’

‘He might not,’ put in Brangstrode. ‘He mightn’t want to make any admissions. Or rather, the captain mightn’t report it at this stage.’

‘If it had been a boiler,’ Crewe pointed out, ‘some of the stokers would almost certainly have been killed. If it had been a steam pipe, it is unlikely it would have done all that damage to the hull. A broken connecting rod might have swung round and plunged through her bottom, and so might a broken tail-shaft. But if any of these things had happened it’s hard to see why the captain would want to keep it a secret.’

‘I’ve heard of the loss of a propeller damaging the stern of a vessel so much that she sank,’ Leatherhead put in.

‘Yes,’ Crewe answered. ‘If damage occurs about the after bulkhead, that’s between the aft hold and the aft peak, so that both those are flooded, the average cargo boat will go down. A passenger boat should float with two adjoining compartments flooded, but not a boat of the type of the Jane Vosper.’

‘You’re quite a sailor,’ Brangstrode intervened.

Crewe laughed. ‘I’m interested, sir,’ he explained. ‘I’ve read a bit about ships.’

‘Passengers are more valuable than freight?’ Leatherhead suggested.

‘I think it’s not that altogether,’ Crewe returned. ‘There are two reasons: first, bulkheads are a nuisance in cargo boats, as they get in the way of stowing the cargo, so they have as few as possible; and second, there are comparatively so few people on a cargo boat, that they have a much better chance of getting away if there’s trouble.’

‘I don’t profess to know anything about the sea,’ said Brangstrode, ‘but I always thought that spontaneous combustion occurred under certain conditions, with probable explosions. Do you know anything about that, Crewe? What about explosions of coal dust in the bunkers?’

Crewe shook his head. ‘I don’t know anything about it, sir. I understand there’s a risk of spontaneous combustion from greasy cotton and other substances. But I don’t know how far there’s danger from coal dust.’

‘That’ll all be cleared up at the enquiry,’ Jeffrey said with some impatience. ‘I don’t see that we’ll gain much by discussing it now.’

‘You’re right, Jeffrey,’ admitted Brangstrode. ‘All the same, I confess to a good deal of interest in the cause of those explosions.’ He paused a moment, then added: ‘So much so that I think we should be represented at the enquiry.’

The others stared. ‘Represented?’ Jeffrey repeated.

‘Represented. Suppose those explosions were not due to what I might call any normal cause: any explainable cause, if you like. Well,’ he shrugged, ‘explosions have been known to occur which damaged insured goods.’

‘You mean,’ Jeffrey said quickly, ‘deliberate? But that wouldn’t affect us. Suppose, if you like, the ship was scuttled. We’d still be liable for our hundred and five thousand.’

‘Possibly,’ Brangstrode admitted, then after a pause added, ‘and possibly not.’

‘Possibly not? I don’t follow you there, sir. What do you mean?’

‘Well,’ Brangstrode shrugged slightly. ‘Suppose a ship is insured and she’s blown up by the owners for the insurance money. If this can be proved, the insurance company doesn’t pay, does it?’

‘Of course not. But the companies that insured the cargo would pay.’

‘Admittedly. But now consider the converse case. Suppose certain cargo was destroyed for the insurance, and suppose as an accidental correlative the ship sank. Who would pay?’

‘I see what you’re suggesting. That if—’

‘I’m suggesting nothing. I’m only pointing out that cases are conceivable in which cargo insured for safe transport by sea, and destroyed en route, need not be paid for.’

Jeffrey shook his head. ‘We’re dealing with Weaver Bannister’s in this matter. They’re a good firm. There’s never been a whisper of anything crooked about them. I see what you mean, but I don’t honestly believe there’s anything in it.’

‘I don’t say there’s anything in it myself. I say we should be represented at the enquiry and be sure.’

‘I wish there was a chance of what you’re hinting at,’ Jeffrey went on with a crooked smile; ‘but really, sir, I’m not with you there. Have you thought what a ghastly crime it would be? Not only the fraud against us, but also against the firms which covered the rest of the cargo and the ship herself. And all that fraud would be the smallest part of it. Why, it might have meant the loss of the whole crew; the murder of the whole crew. No, I don’t see Weaver Bannister or anyone else standing for that.’

Brangstrode shrugged. ‘I agree with all that,’ he admitted. ‘All the same, I don’t see that it is any reason against our being represented.’

‘Oh no, I admit that. I expect it would be a wise enough precaution. I suppose Alexander?’

‘I think so. Let’s consult him at all events. What about ringing him up now?’

Herbert Alexander, senior partner of Alexander, Alexander & Phillimore, Solicitors, occupied offices on the eighth floor of the same building as the Land & Sea Insurance Company. Though their practice was nominally general, the partners had specialized largely on insurance law. Nor had they neglected the criminal side of the subject, and they were recognized authorities on insurance frauds, arson, and even murder.

Alexander replied that he was disengaged, and five minutes later he entered the room. He was not unlike the chairman in appearance, tall, aquiline, and with the same suggestion of latent force.

‘You just rang up in time,’ he declared, as he took the armchair Crewe vacated. ‘Another twenty seconds and I should have gone out to lunch.’

‘Sorry for keeping you then,’ Brangstrode returned. ‘Perhaps as I’ve spoiled your plans, you’ll lunch with me afterwards?’

‘I never,’ said Alexander gravely, ‘refuse a good offer. I shall be delighted.’

‘Very good.’ The chairman turned to Jeffrey. ‘Tell him, Jeffrey, will you?’

‘It’s about a consignment of petrol sets Messrs Weaver Bannister of Watford were sending to South America,’ the manager began, and he recounted what had taken place. ‘I think the immediate question is whether you advise our being represented at the Board of Trade enquiry? That’s right, sir?’

‘That’s the point,’ agreed the chairman. ‘It was I who raised it, but I don’t wish to push it against all of you.’

‘There’s been no explanation of these explosions?’ asked Alexander.

‘None,’ Jeffrey answered, ‘but it’s only fair to add that there has been no opportunity to get one.’

The solicitor asked a number of other questions. ‘Quite,’ he concluded, ‘I’ll consider the matter and let you have an opinion. In the meantime and speaking without proper thought, it seems to me that if between this and the enquiry no explanation of the affair is put up which satisfies you people, an attendance at the enquiry would do no harm. In fact it might be better for me to apply to be made a party to it. Under the circumstances this would certainly be granted.’

‘Just what exactly does that mean?’ Brangstrode asked.

‘Well, if for instance an underwriter suspects an insured vessel has been cast away, or a certificated officer wishes to have his character cleared of damaging imputations, he may apply to be made a party to the enquiry. It gives him a locus standi and enables him to see that any evidence he wants is called, and so on. In our case it would strengthen our position if we afterwards wished to. dispute the claim.’

‘That seems a good idea,’ the chairman approved. ‘I should make the application.’ He looked at Jeffrey, who nodded.

‘I shall do so,’ Alexander promised. ‘Now there is one other point. If I’m really to go into this matter seriously, I’d like to have Sutton with me.’

John Sutton was a private detective employed by the Land and Sea, as well as by certain other insurance firms. He investigated doubtful cases, both beforehand, when the question of granting the cover was being considered, and afterwards, if what seemed a fraudulent claim had been made. Sutton was a first-rate man, extremely reliable, and as pertinacious and thorough as they were made.

Jeffrey raised his eyes at the solicitor’s proposal, but the chairman declared it was only common sense. ‘There’s no earthly use in half doing anything; though I don’t suggest,’ he smiled crookedly at the lawyer, ‘that without Sutton that’s what you’d do. But undoubtedly if we do suspect anything, Sutton should know all there’s to be known about it from the beginning.’