Полная версия

Think Like a Monk

Back Slowly Away

From a position of understanding, we are better equipped to address negative energy. The simplest response is to back slowly away. Just as in the last chapter we let go of the influences that interfered with our values, we want to cleanse ourselves of the negative attitudes that cloud our outlook. In The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, Thich Nhat Hanh, a Buddhist monk who has been called the Father of Mindfulness, writes, “Letting go gives us freedom, and freedom is the only condition for happiness. If, in our heart, we still cling to anything—anger, anxiety, or possessions—we cannot be free.” I encourage you to purge or avoid physical triggers of negative thoughts and feelings, like that sweatshirt your ex gave you or the coffee shop where you always run into a former friend. If you don’t let go physically, you won’t let go emotionally.

But when a family member, a friend, or a colleague is involved, distancing ourselves is often not an option or not the first response we want to give. We need to use other strategies.

The 25/75 Principle

For every negative person in your life, have three uplifting people. I try to surround myself with people who are better than I am in some way: happier, more spiritual. In life, as in sports, being around better players pushes you to grow. I don’t mean for you to take this so literally that you label each of your friends either negative or uplifting, but aim for the feeling that at least 75 percent of your time is spent with people who inspire you rather than bring you down. Do your part in making the friendship an uplifting exchange. Don’t just spend time with the people you love—grow with them. Take a class, read a book, do a workshop. Sangha is the Sanskrit word for community, and it suggests a refuge where people serve and inspire each other.

Allocate Time

Another way to reduce negativity if you can’t remove it is to regulate how much time you allow a person to occupy based on their energy. Some challenges we face only because we allow them to challenge us. There might be some people you can only tolerate for an hour a month, some for a day, some for a week. Maybe you even know a one-minute person. Consider how much time is best for you to spend with them, and don’t exceed it.

Don’t Be a Savior

If all someone needs is an ear, you can listen without exerting much energy. If we try to be problem-solvers, then we become frustrated when people don’t take our brilliant advice. The desire to save others is ego-driven. Don’t let your own needs shape your response. In Sayings of the Fathers, a compilation of teachings and maxims from Jewish Rabbinic tradition, it is advised, “Don’t count the teeth in someone else’s mouth.” Similarly, don’t attempt to fix a problem unless you have the necessary skills. Think of your friend as a person who is drowning. If you are an excellent swimmer, a trained lifeguard, then you have the strength and wherewithal to help a swimmer in trouble. Similarly, if you have the time and mind space to help another person, go for it. But if you’re only a fair swimmer and you try to save a drowning person, they are likely to pull you down with them. Instead, you call for the lifeguard. Similarly, if you don’t have the energy and experience to help a friend, you can introduce them to people or ideas that might help them. Maybe someone else is their rescuer.

REVERSE INTERNAL NEGATIVITY

Working from the outside in is the natural way of decluttering. Once we recognize and begin to neutralize the external negativities, we become better able to see our own negative tendencies and begin to reverse them.

Sometimes we deny responsibility for the negativity that we ourselves put out in the world, but negativity doesn’t always come from other people and it isn’t always spoken aloud. Envy, complaint, anger—it’s easier to blame those around us for a culture of negativity, but purifying our own thoughts will protect us from the influence of others.

In the ashram our aspirations for purity were so high that our “competition” came in the form of renunciation (“I eat less than that monk”; “I meditated longer than everyone else”). But a monk has to laugh at himself if the last thought he has at the end of the meditation is “Look at me! I outlasted them all!” If that’s where he arrived, then what was the point of the meditation? In The Monastic Way, a compilation of quotes edited by Hannah Ward and Jennifer Wild, Sister Christine Vladimiroff says, “[In a monastery], the only competition allowed is to outstrip each other in showing love and respect.”

Competition breeds envy. In the Mahabharata, an evil warrior envies another warrior and wants him to lose all he has. The evil warrior hides a burning block of coal in his robes, planning to hurl it at the object of his envy. Instead, it catches fire and the evil warrior himself is burned. His envy makes him his own enemy.

Envy’s catty cousin is Schadenfreude, which means taking pleasure in the suffering of others. When we derive joy from other people’s failures, we’re building our houses and pride on the rocky foundations of someone else’s imperfection or bad luck. That is not steady ground. In fact, when we find ourselves judging others, we should take note. It’s a signal that our minds are tricking us into thinking we’re moving forward when in truth we’re stuck. If I sold more apples than you did yesterday, but you sold more today, this says nothing about whether I’m improving as an apple seller. The more we define ourselves in relation to the people around us, the more lost we are.

We may never completely purge ourselves of envy, jealousy, greed, lust, anger, pride, and illusion, but that doesn’t mean we should ever stop trying. In Sanskrit, the word anartha generally means “things not wanted,” and to practice anartha-nivritti is to remove that which is unwanted. We think freedom means being able to say whatever we want. We think freedom means that we can pursue all our desires. Real freedom is letting go of things not wanted, the unchecked desires that lead us to unwanted ends.

Letting go doesn’t mean wiping away negative thoughts, feelings, and ideas completely. The truth is that these thoughts will always arise—it is what we do with them that makes the difference. The neighbor’s barking dog is an annoyance. It will always interrupt you. The question is how you guide that response. The key to real freedom is self-awareness.

In your evaluation of your own negativity, keep in mind that even small actions have consequences. Even when we become more aware of others’ negativity and say, “She’s always complaining,” we ourselves are being negative. At the ashram, we slept under mosquito nets. Every night, we’d close our nets and use flashlights to confirm that they were clear of bugs. One morning, I woke up to discover that a single mosquito had been in my net and I had at least ten bites. I thought of something the Dalai Lama said, “If you think you are too small to make a difference, try sleeping with a mosquito.” Petty, negative thoughts and words are like mosquitos: Even the smallest ones can rob us of our peace.

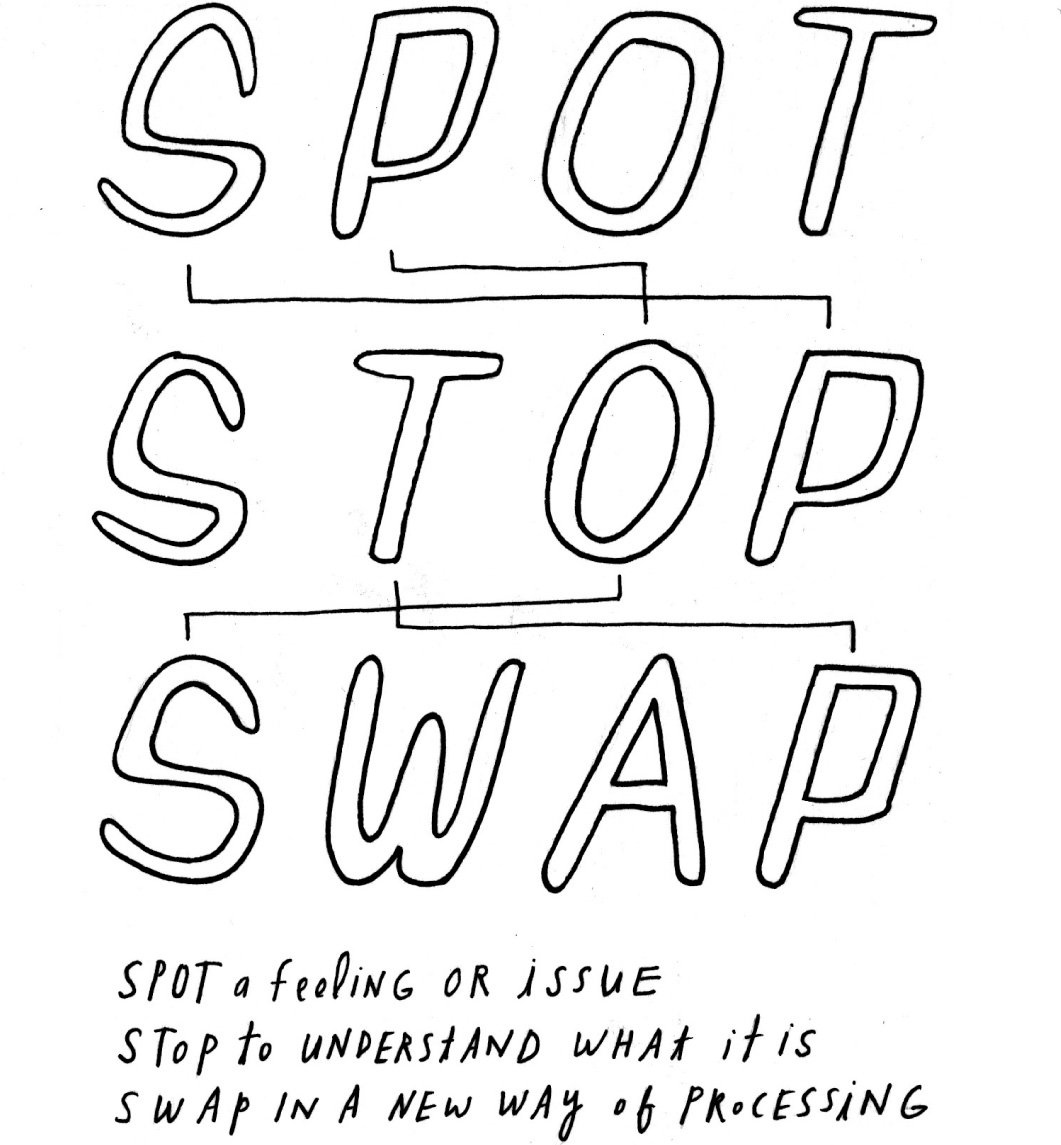

Spot, Stop, Swap

Most of us don’t register our negative thoughts, much as I didn’t register that sole mosquito. To purify our thoughts, monks talk about the process of awareness, addressing, and amending. I like to remember this as spot, stop, swap. First, we become aware of a feeling or issue—we spot it. Then we pause to address what the feeling is and where it comes from—we stop to consider it. And last, we amend our behavior—we swap in a new way of processing the moment. SPOT, STOP, SWAP.

Spot

Becoming aware of negativity means learning to spot the toxic impulses around you. To help us confront our own negativity, our monk teachers told us to try not to complain, compare, or criticize for a week, and keep a tally of how many times we failed. The goal was to see the daily tally decrease. The more aware we became of these tendencies, the more we might free ourselves from them.

Listing your negative thoughts and comments will help you contemplate their origins. Are you judging a friend’s appearance, and are you equally hard on your own? Are you muttering about work without considering your own contribution? Are you reporting on a friend’s illness to call attention to your own compassion, or are you hoping to solicit more support for that friend?

TRY THIS: AUDIT YOUR NEGATIVE COMMENTS.

Keep a tally of the negative remarks you make over the course of a week. See if you can make your daily number go down. The goal is zero.

Sometimes instead of reacting negatively to what is, we negatively anticipate what might be. This is suspicion. There’s a parable about an evil king who went to meet a good king. When invited to stay for dinner, the evil king asked for his plate to be switched with the good king’s plate. When the good king asked why, the evil king replied, “You may have poisoned this food.”

The good king laughed.

That made the evil king even more nervous, and he switched the plates again, thinking maybe he was being double-bluffed. The good king just shook his head and took a bite of the food in front of him. The evil king didn’t eat that night.

What we judge or envy or suspect in someone else can guide us to the darkness we have within ourselves. The evil king projects his own dishonor onto the good king. In the same way our envy or impatience or suspicion with someone else tells us something about ourselves. Negative projections and suspicions reflect our own insecurities and get in our way. If you decide your boss is against you, it can affect you emotionally—you might be so discouraged that you don’t perform well at work—or practically—you won’t ask for the raise you deserve. Either way, like the evil king, you’re the one who will go hungry!

Stop

When you better understand the roots of your negativity, the next step is to address it. Silence your negativity to make room for thoughts and actions that add to your life instead of taking away from it. Start with your breath. When we’re stressed, we hold our breath or clench our jaws. We slump in defeat or tense our shoulders. Throughout the day, observe your physical presence. Is your jaw tight? Is your brow furrowed? These are signs that we need to remember to breathe, to loosen up physically and emotionally.

The Bhagavad Gita refers to the austerity of speech, saying that we should only speak words that are truthful, beneficial to all, pleasing, and that don’t agitate the minds of others. The Vaca Sutta, from early Buddhist scriptures, offers similar wisdom, defining a well-spoken statement as one that is “spoken at the right time. It is spoken in truth. It is spoken affectionately. It is spoken beneficially. It is spoken with a mind of goodwill.”

Remember, saying whatever we want, whenever we want, however we want, is not freedom. Real freedom is not feeling the need to say these things.

When we limit our negative speech, we may find that we have a lot less to say. We might even feel inhibited. Nobody loves an awkward silence, but it’s worth it to free ourselves from negativity. Criticizing someone else’s work ethic doesn’t make you work harder. Comparing your marriage to someone else’s doesn’t make your marriage better unless you do so thoughtfully and productively. Judgment creates an illusion: that if you see well enough to judge, then you must be better, that if someone else is failing, then you must be moving forward. In fact, it is careful, thoughtful observations that move us forward.

Stopping doesn’t mean simply shunning the negative instinct. Get closer to it. Australian community worker Neil Barringham said, “The grass is greener where you water it.” Notice what’s arousing your negativity, over there on your frenemy’s side of the fence. Do they seem to have more time, a better job, a more active social life? Because in the third step, swapping, you’ll want to look for seeds of the same on your turf and cultivate them. For example, take your envy of someone else’s social whirlwind and in it find the inspiration to host a party, or get back in touch with old friends, or organize an after-work get-together. It is important to find our significance not from thinking other people have it better but from being the person we want to be.

Swap

After spotting and stopping the negativity in your heart, mind, and speech, you can begin to amend it. Most of us monks were unable to completely avoid complaining, comparing, and criticizing—and you can’t expect you’ll be completely cured of that habit either—but researchers have found that happy people tend to complain … wait for it … mindfully. While thoughtlessly venting complaints makes your day worse, it’s been shown that writing in a journal about upsetting events, giving attention to your thoughts and emotions, can foster growth and healing, not only mentally, but also physically.

We can be mindful of our negativity by being specific. When someone asks how we are, we usually answer, “good,” “okay,” “fine,” or “bad.” Sometimes this is because we know a truthful, detailed answer is not expected or wanted, but we tend to be equally vague when we complain. We might say we’re angry or sad when we’re offended or disappointed. Instead, we can better manage our feelings by choosing our words carefully. Instead of describing ourselves as feeling angry, sad, anxious, hurt, embarrassed, and happy, the Harvard Business Review lists nine more specific words that we could use for each one of these emotions. Instead of being angry, we might better describe ourselves as annoyed, defensive, or spiteful. Monks are considered quiet because they are trained to choose their words so carefully that it takes some time. We choose words carefully and use them with purpose.

So much is lost in bad communication. For example, instead of complaining to a friend, who can’t do anything about it, that your partner always comes home late, communicate directly and mindfully with your partner. You might say, “I appreciate that you work hard and have a lot to balance. When you come home later than you promised, it drives me crazy. You could support me by texting me as soon as you know you’re running late.” When our complaints are understood—by ourselves and others—they can be more productive.

In addition to making our negativity more productive, we can also deliberately swap in positivity. One way to do this, as I mentioned, is to use our negativity—like envy—to guide us to what we want. But we can also swap in new feelings. In English, we have the words “empathy” and “compassion” to express our ability to feel the pain that others suffer, but we don’t have a word for experiencing vicarious joy—joy on behalf of other people. Perhaps this is a sign that we all need to work on it. Mudita is the principle of taking sympathetic or unselfish joy in the good fortune of others.

If I only find joy in my own successes, I’m limiting my joy. But if I can take pleasure in the successes of my friends and family—ten, twenty, fifty people!—I get to experience fifty times the happiness and joy. Who doesn’t want that?

The material world has convinced us that there are only a limited number of colleges worth attending, a limited number of good jobs available, a limited number of people who get lucky. In such a finite world, there’s only so much success and happiness to go around, and whenever other people experience them, your chances of doing so decrease. But monks believe that when it comes to happiness and joy, there is always a seat with your name on it. In other words, you don’t need to worry about someone taking your place. In the theater of happiness, there is no limit. Everyone who wants to partake in mudita can watch the show. With unlimited seats, there is no fear of missing out.

Radhanath Swami is my spiritual teacher and the author of several books, including The Journey Home. I asked him how to stay peaceful and be a positive force in a world where there is so much negativity. He said, “There is toxicity everywhere around us. In the environment, in the political atmosphere, but the origin is in people’s hearts. Unless we clean the ecology of our own heart and inspire others to do the same, we will be an instrument of polluting the environment. But if we create purity in our own heart, then we can contribute great purity to the world around us.”

TRY THIS: REVERSE ENVY

Make a list of five people you care about, but also feel competitive with. Come up with at least one reason that you’re envious of each one: something they’ve achieved, something they’re better at, something that’s gone well for them. Did that achievement actually take anything away from you? Now think about how it benefitted your friend. Visualize everything good that has come to them from this achievement. Would you want to take any of these things away if you could, even knowing that they would not come to you? If so, this envy is robbing you of joy. Envy is more destructive to you than whatever your friend has accomplished. Spend your energy transforming it.

KṢAMĀ: AMENDING ANGER

We’ve talked about strategies to manage and minimize the daily negativity in your life. But nuisances like complaining, comparing, and gossip can feel manageable next to bigger negative emotions like pain and anger. We all harbor anger in some form: anger from the past, or anger at people who continue to play a big role in our lives. Anger at misfortune. Anger at the living and the dead. Anger turned inward.

When we are deeply wounded, anger is often part of the response. Anger is a great, flaming ball of negative emotion, and when we cannot let it go, no matter how we try, the anger takes on a life of its own. The toll is enormous. I want to talk specifically about how to deal with anger we feel toward other people.

Kṣamā is Sanskrit for forgiveness. It suggests that you bring patience and forbearance to your dealings with others. Sometimes we have been wounded so deeply that we can’t imagine how we might forgive the person who hurt us. But, contrary to what most of us believe, forgiveness is primarily an action we take within ourselves. Sometimes it’s better (and safer and healthier) not to have direct contact with the person at all; other times, the person who hurt us is no longer around to be forgiven directly. But those factors don’t impede forgiveness because it is, first and foremost, internal. It frees you from anger.

One of my clients told me, “I had to reach back to my childhood to pinpoint why I felt unloved and unworthy. My paternal grandmother set the tone for this feeling. I realized she treated me differently because she didn’t like my mother. [I had to] forgive her even though she passed on already. I realized I was always worthy and always lovable. She was broken, not I.”

The Bhagavad Gita describes three gunas, or modes of life: tamas, rajas, and sattva, which represent “ignorance,” “impulsivity,” and “goodness.” I have found that these three modes can be applied to any activity—for example, when you pull back from a conflict and look for understanding, it’s very useful to try to shift from rajas—impulsivity and passion—to sattva—goodness, positivity, and peace. These modes are the foundation of my approach to forgiveness.

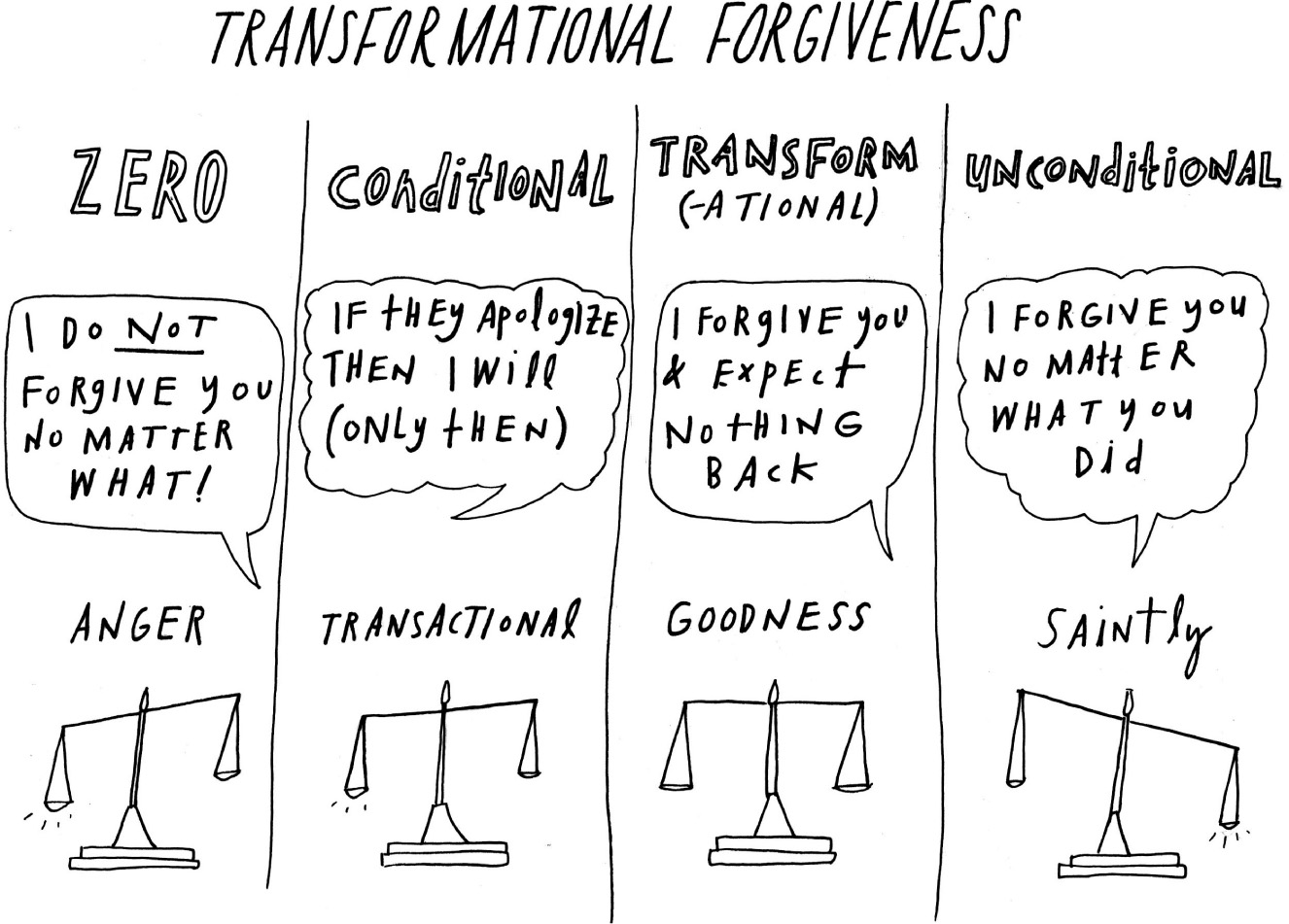

TRANSFORMATIONAL FORGIVENESS

Before we find our way to forgiveness, we are stuck in anger. We may even want revenge, to return the pain that a person has inflicted on us. An eye for an eye. Revenge is the mode of ignorance—it’s often said that you can’t fix yourself by breaking someone else. Monks don’t hinge their choices and feelings on others’ behaviors. You believe revenge will make you feel better because of how the other person will react. But when you make your vindictive play and the person doesn’t have the response you fantasized about—guess what? You only feel more pain. Revenge backfires.

When you rise above revenge, you can begin the process of forgiveness. People tend to think in binary terms: You either forgive someone, or you don’t forgive someone, but (as I will suggest more than once in this book) there are often multiple levels. These levels give us leeway to be where we are, to progress in our own time, and to climb only as far as we can. On the scale of forgiveness, the bottom (though it is higher than revenge) is zero forgiveness. “I am not going to forgive that person, no matter what. I don’t want to hurt them, but I’m never going to forgive them.” On this step we are still stuck in anger, and there is no resolution. As you might imagine, this is an uncomfortable place to stay.

The next step is conditional forgiveness: If they apologize, then I’ll apologize. If they promise never to do it again, I’ll forgive them. This transactional forgiveness comes from the mode of impulse—driven by the need to feed your own emotions. Research at Luther College shows that forgiving appears to be easier when we get (or give) an apology, but I don’t want us to focus on conditional forgiveness. I want you to rise higher.

The next step is something called transformational forgiveness. This is forgiveness in the mode of goodness. In transformational forgiveness, we find the strength and calmness to forgive without expecting an apology or anything else in return.

There is one level higher on the forgiveness ladder: unconditional forgiveness. This is the level of forgiveness that a parent often has for a child. No matter what that child does or will do, the parent has already forgiven them. The good news is, I’m not suggesting you aim for that. What I want you to achieve is transformational forgiveness.

PEACE OF MIND

Forgiveness has been shown to bring peace to our minds. Forgiveness actually conserves energy. Transformational forgiveness is linked to a slew of health improvements including: fewer medications taken, better sleep quality, and reduced somatic symptoms including back pain, headache, nausea, and fatigue. Forgiveness eases stress, because we no longer recycle the angry thoughts, both conscious and subconscious, that stressed us out in the first place.

In fact, science shows that in close relationships, there’s less emotional tension between partners when they’re able to forgive each other, and that promotes physical well-being. In a study published in a 2011 edition of the journal Personal Relationships, sixty-eight married couples agreed to have an eight-minute talk about a recent incident where one spouse “broke the rules” of the marriage. The couples then separately watched replays of the interviews and researchers measured their blood pressure. In couples where the “victim” was able to forgive their spouse, both partners’ blood pressure decreased. It just goes to show that forgiveness is good for everyone.

Giving and receiving forgiveness both have health benefits. When we make forgiveness a regular part of our spiritual practice, we start to notice all of our relationships blossoming. We’re no longer holding grudges. There’s less drama to deal with.

TRY THIS: ASK FOR AND RECEIVE FORGIVENESS