Полная версия

Gulls

GULL HABITATS

The majority of gull species frequent coastal areas, marshes, rivers, estuaries and large inland lakes. Many occupy the same habitat zones used by marsh and sea terns, and in this respect they contrast markedly with shearwaters and petrels, which are pelagic. The smaller species often feed and breed inland, while the larger gulls breed mainly at coastal sites. Within the last hundred years, several species of large gulls have bred inland more frequently, a change in behaviour that has coincided with their overall increase in abundance.

Gulls breeding on the coast move only moderate distances from the shore. They are tied by relatively short incubation shifts and the need to feed their young frequently and regularly. In general, the density of gulls at sea tends to decline rapidly as the distance from shore increases, although the Kittiwake does not show this tendency in winter. Outside the breeding season, most gulls remain within daily flying distance of the shore, preferring to roost overnight on land or on sheltered coastal waters. The exception to this is when they are migrating. Only the two kittiwake species, Sabine’s Gull and Ross’s Gull, occur regularly in oceanic waters far from land throughout the long non-breeding season.

GULL SPECIES RECORDED IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND

The box is the current list of 26 species recorded in Britain and Ireland as breeding species, regular visitors or occasional vagrants. The list represents about half of all gull species in the world. Kumlien’s Gull is listed, but is retained as a subspecies of the Iceland Gull.

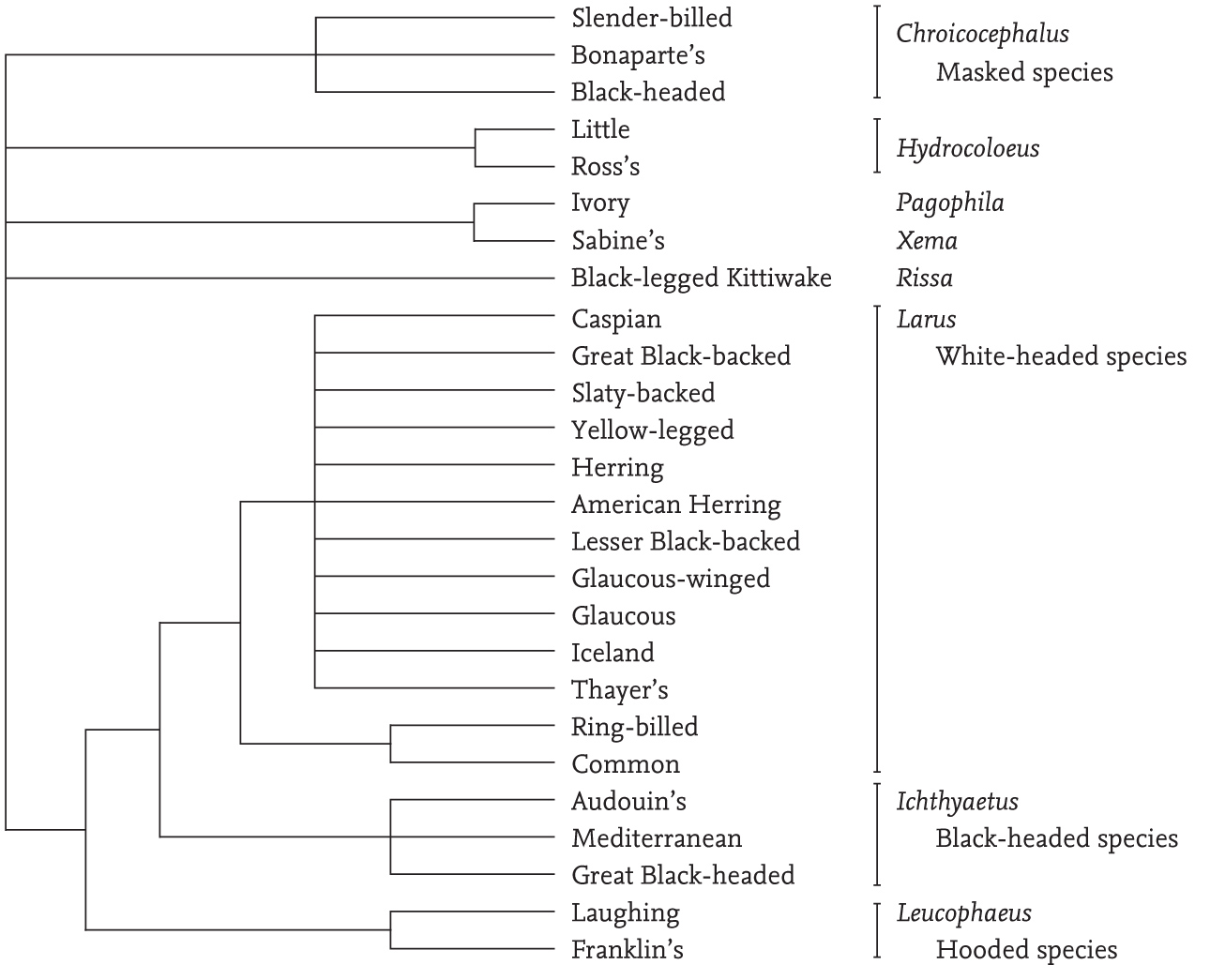

An approximate phylogenetic tree of the evolution of gull species recorded in Britain and Ireland (mainly based on the research by Pons and colleagues) is shown in Fig. 3 and involves eight genera. Such a representation can be only approximate, as their evolution has most likely been multi-dimensional and so cannot be presented accurately in two dimensions. There is still considerable uncertainty about the relationships between the species in the genus Larus, and no attempt is made in the order shown in Fig. 3 to indicate these, other than to suggest that the species with totally white wing-tips probably represent a distinct group.

Audouin’s Gull, which lacks a black head at any time, is placed in the same genus (Ichthyaetus) as two black-headed species on the British list (Mediterranean Gull and Great Black-headed Gull), along with three other black-headed species that occur elsewhere in the world, so its inclusion is surprising. Similarly, the Slender-billed Gull, which has a white head in all seasons, is included with the dark-headed Black-headed and Bonaparte’s gulls. However, Jean-Marc Pons in response to my query believes that ‘the dark hood is not a good character to construct evolutionary relationships because it has repeatedly been lost during the evolution of gulls’. In addition, he confirms that there is additional evidence indicating that the Black-headed and Bonaparte’s gulls should be included in the genera Ichthyaetus and Chroicocephalus, respectively.

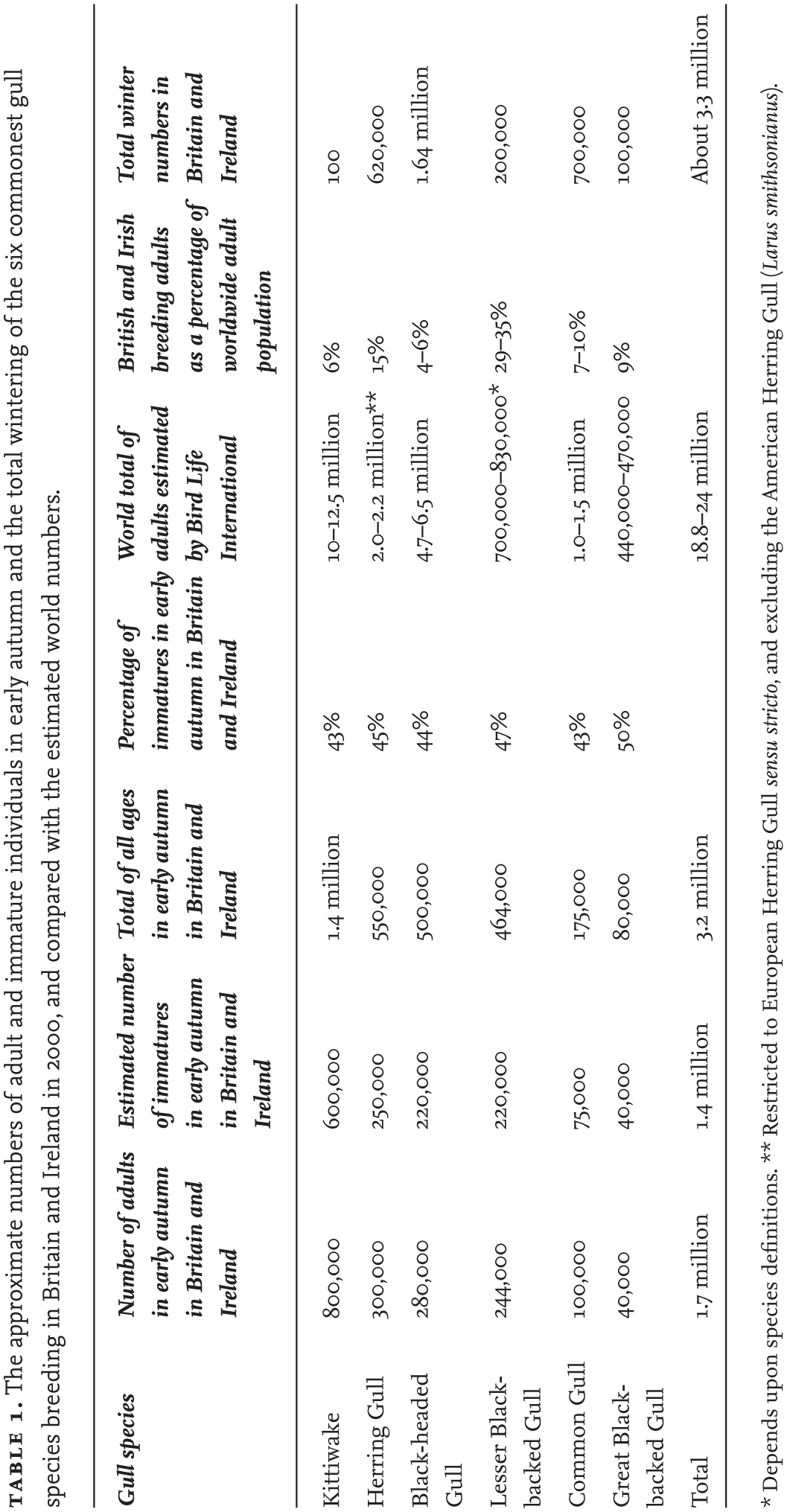

The national censuses of gulls and other seabirds have been incredibly important and informative, and at last we have a sound knowledge of both the distribution and numbers of adults. However, we do not have a census value for numbers of immature individuals that have never bred for any of the gull species. Since immature birds may include up to five year classes (varying according to species), the numbers involved are appreciable and can be estimated only from a life table formed from survival rates obtained from detailed marking studies. Table 1 gives rough estimates of the proportion of immature gulls of the six commonest species occurring in Britain and Ireland. The figures are approximations but indicate that, by autumn, there is a large proportion (probably about 40 per cent) of individuals of every species listed that have not yet matured and bred. The proportions of immature individuals will have decreased by early spring because the mortality rate of young birds in their first year of life is usually markedly higher than that of adults, but they will still form an appreciable minority of the numbers of each species.

Gulls recorded in Britain and Ireland

Genus Hydrocoloeus Little Gull (H. minutus) Regular visitor, very occasional breeder Ross’s Gull (H. roseus) Vagrant Genus Xema Sabine’s Gull (X. sabini) Regular visitor, usually in small numbers Genus Pagophila Ivory Gull (P. eburnea) Vagrant Genus Chroicocephalus Slender-billed Gull (C. genei) Rare vagrant Bonaparte’s Gull (C. philadelphia) Vagrant Black-headed Gull (C. ridibundus) Abundant breeder and winter visitor Genus Larus Common Gull (L. canus) Common breeder and winter visitor Ring-billed Gull (L. delawarensis) Vagrant Great Black-backed Gull (L. marinus) Common breeder and winter visitor Glaucous-winged Gull (L. glaucescens) Vagrant Glaucous Gull (L. hyperboreus) Regular winter visitor Iceland Gull (L. glaucoides) Regular winter visitor Kumlien’s Gull (L. glaucoides kumlieni) Vagrant subspecies Thayer’s Gull (L. thayeri) Vagrant European Herring Gull (L. argentatus) Abundant breeder and winter visitor American Herring Gull (L. smithsonianus) Vagrant Caspian Gull (L. cachinnans) Currently vagrant but increasingly recorded Yellow-legged Gull (L. michahellis) Visitor and now an occasional breeder Lesser Black-backed Gull (L. fuscus) Abundant breeder Slaty-backed Gull (L. schistisagus) Vagrant Genus Ichthyaetus Great Black-headed Gull or Pallas’s Gull (I. ichthyaetus) Vagrant Mediterranean Gull (I. melanocephalus) Rapidly increasing breeder Audouin’s Gull (I. audouinii) Vagrant Genus Leucophaeus Laughing Gull (L. atricilla) Vagrant Franklin’s Gull (L. pipixcan) Vagrant Genus Rissa Black-legged Kittiwake (R. tridactyla) Abundant breeder

FIG 3. A phylogenetic tree of the gull species that occur in Britain and Ireland. In general, the shorter the line leading from each species, the more recently that species is presumed to have arisen. This does not apply to the large genus Larus, where more work is necessary to elucidate the affinities of the different species. This diagram includes all of the genera in the world, with the exception of the genus Saundersilarus (where Saunders’s Gull, S. saundersi, is the only species) and the genus Creagrus (where the Swallow-tailed Gull, C. furcatus, is the only species), neither of which occur in Europe. The Vega Gull (L. vegae) has not been included, and its presence in Britain has yet to be confirmed, while Kumlein’s Gull is regarded as a subspecies of the Iceland Gull. Based in part on the work of Pons et al. (2005).

Table 1 also shows estimates of numbers of the six most abundant gulls in Britain and Ireland in about 2000. Again, these figures are estimates, but they indicate that for all six species combined there are about 3.2 million gulls of all ages in Britain and Ireland in the early autumn. This total is probably about 3.3 million in winter, when the numbers of departing Kittiwakes are replaced by immigrant Black-headed, Herring and Common gulls. By late spring, the winter visitors have departed and Kittiwakes have returned to their colonies, maintaining numbers at about 2.6 million just before breeding begins.

SUBSPECIES IN WESTERN EUROPE

There are only a few western European gull species that are represented by more than one subspecies. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the Herring Gull was previously split into several named subspecies, some of which have now been elevated to species (Yellow-legged Gull, Caspian Gull). Two subspecies occur in Britain and Ireland: Larus argentatus argenteus, which breeds here; and the larger, darker L. a. argentatus, which breeds in northern Scandinavia and north-west Russia, and winters in Britain and the North Sea region. The nominate Common Gull subspecies, L. canus canus, occurs widely in western Europe, while the larger, darker subspecies L. c. heinei, which breeds in Russia, probably (based on ringing data) occurs occasionally in Britain, but is difficult to identify. In the Atlantic, the Kittiwake is represented by a single subspecies (Rissa tridactyla tridactyla); individuals are progressively larger towards the north of its range, but this gradual change does not justify separate subspecies status and is described as a cline. There are probably several other clines among gulls that are yet to be recognised, including the Black-headed Gull, Glaucous Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull.

SURVIVAL AND LONGEVITY

Gulls are medium- to long-lived birds, with an average expectation of adult life and number of breeding years of different species ranging between four and 12 or more years. Annual adult survival rates for different species vary between 80 per cent and 92 per cent, and often vary appreciably from year to year and over longer periods of time. The annual survival rate tends to be higher in the larger gulls, which also have a longer period of immaturity. This delay in reaching breeding age in gulls appears to be associated with the time that is necessary to acquire competence in obtaining food, but why this should be longer in the large species is not evident. Ringed Herring Gulls that are nearly 35 years old have been recorded, but these represent a few extreme individuals comprising less than 1 per cent of those that reached maturity. In several gull species, the peak of mortality occurs during and just after the breeding season, when the adults are at their lowest weights during the year, suggesting that breeding is a significant stress. Data suggest that survival of gulls is usually high in winter, but the Kittiwake may be an exception, with most mortality occurring while the species is in its pelagic wintering range.

Less is known of the survival of immature gulls, but there is usually a lower survival rate in the 12 months following fledging, after which the survival rate approaches that of the adults.

The longevity records based on birds ringed as nestlings and living under natural conditions are given below, although several individuals are known to have lived longer in captivity.

Mediterranean Gull 22 years 1 month Little Gull 20 years 11 months Black-headed Gull 30 years 7 months Common Gull 33 years 8 months Lesser Black-backed Gull 34 years 10 months European Herring Gull 34 years 9 months Great Black-backed Gull 29 years 2 months Black-legged Kittiwake 28 years 6 months Ivory Gull 23 years 11 months Laughing Gull 22 years 1 month Ring-billed Gull 27 years 6 months Glaucous-winged Gull 23 years 10 monthsThe species with the longest recorded lifespans are mainly those that have been ringed in large numbers, and therefore have more chance of an exceptional record. It should be kept in mind that these lifespans are reached by exceptional individuals – perhaps one in several thousand – and so it is very likely that the maximum known age of many gull species in the wild will increase in future years as more recoveries of marked birds accumulate.

SIZE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SPECIES

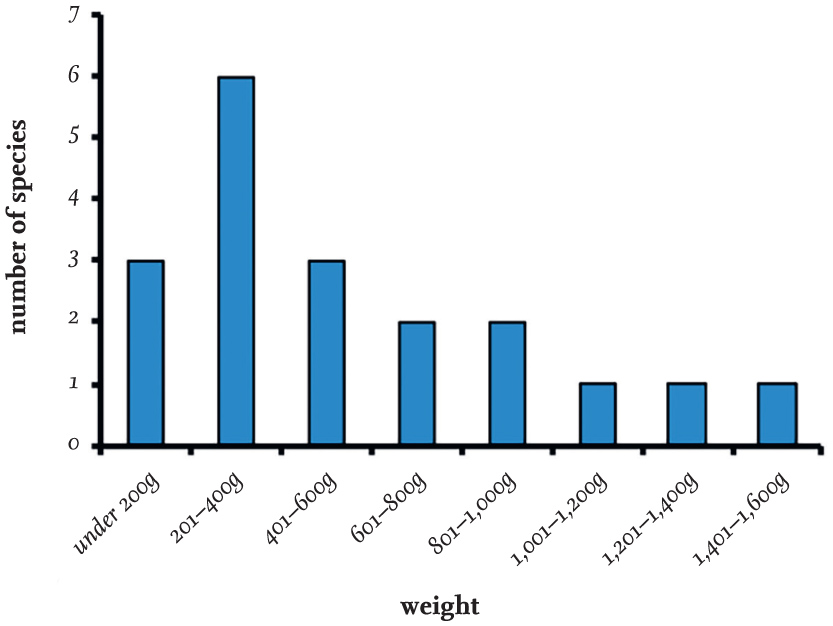

Gull species vary considerably in size. The Little Gull is the smallest and weighs about 100 g (the weight of an Arctic Tern, Sterna paradisaea), while the largest is the Great Black-backed Gull, with males averaging 1,800 g and some individuals exceeding 2,000 g. Fig. 4 shows the average weights of adult females of 19 gull species on the British list. The weights of females of nine of these species are less than 400 g on average and overlap with terns, of which the adult females of all except one species on the British breeding list weigh under 400 g. The distribution chart for male weights is similar, but is shifted to the right because of their slightly greater size.

FIG 4. The average weight of the females of 19 gull species on the British list.

INDIVIDUAL VARIATION

Like all animals, individuals of each gull species show variation in many characters, including size, colour and age at first breeding. Males are larger than females and tend to have a more substantial bill, and size within a species can also vary geographically.

Variation in the immature plumage is widespread in gulls of the same age and this is frequently overlooked in the field identification of species, particularly within the genus Larus. The occurrence of hybrid individuals further adds to plumage variation and typical examples of hybrids can often be identified in the field by experienced observers; the characteristics used often overlap with those of other species. Consequently a proportion of immature and even adult birds that are infrequently recorded in Britain and Ireland may fail to be identified because of potential confusion with other species.

Immature plumages

The plumage, leg and bill colours of recently fledged chicks are very different from those of their parents, to such an extent that, many years ago, a first-year Kittiwake was claimed as a species new to science, despite the adult having already been described and named some years earlier. The first plumage of the young of most gull species is made up of feathers of varying shades of brown and grey, producing a cryptic pattern that helps to conceal them in vegetation in a colony and also appears to reduce aggression from adults. In the smaller gull species, the plumage is replaced by one that resembles the adult at the first annual moult; that is, when the bird is 13 months or so old. In the larger species, all feathers are replaced each year, but only some of the new ones resemble those of the adults and the full adult plumage pattern is not achieved until four years after hatching. These progressive changes in plumage at successive annual moults can vary between individuals and produce a series of different plumage patterns that make it a challenge to identify both the species and the age of immature individuals.

The slow and progressive acquisition of the adult plumage through successive moults contrasts with the rapid growth of bones and wing feathers, which reach full size within a few weeks after hatching because they are necessary before flight can be achieved. Why the acquisition of the adult plumage takes longer in the larger species of gull than in the smaller ones is not clear. The mechanism determining plumage patterns is obviously controlled by hormones and is linked with the greater length of immaturity in the larger gull species, but it is not evident why the large species delay reaching maturity for so long.

Differences between the sexes

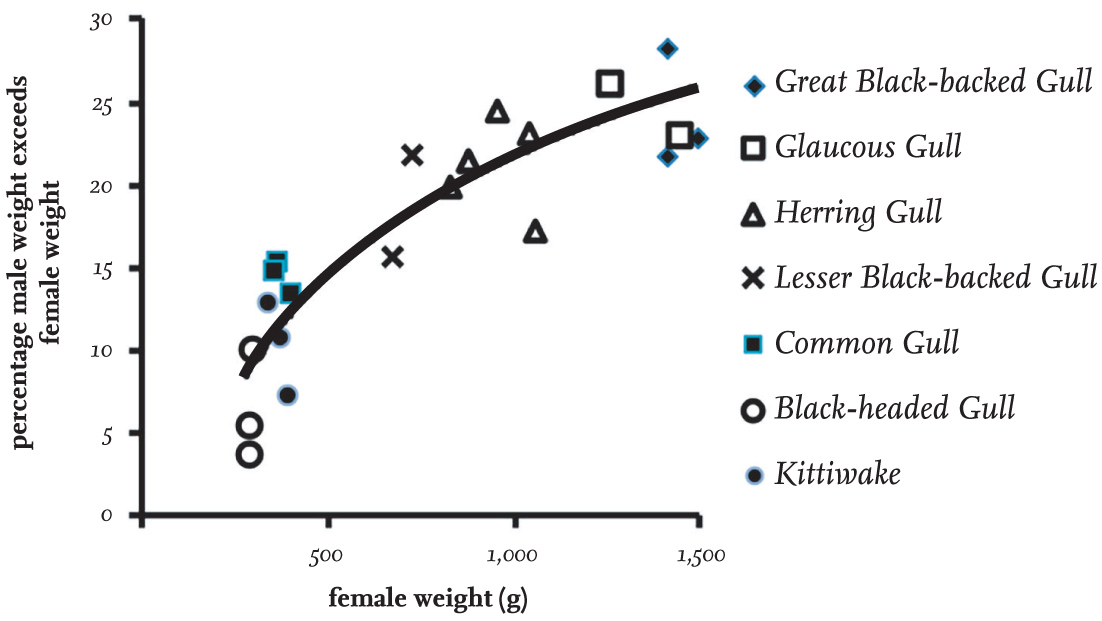

The sexes of gulls have identical plumage and differ only in that females are usually smaller and tend to have slightly less substantial bills. Fig. 5 shows the relationship between the differences in weight of male and female gulls of seven species, using data from different parts of their geographical ranges where available. The extent of the difference between sexes is not constant from species to species, but increases with the weight of the species, ranging from a 5 per cent increase in the Black-headed Gull to more than 20–25 per cent in large species.

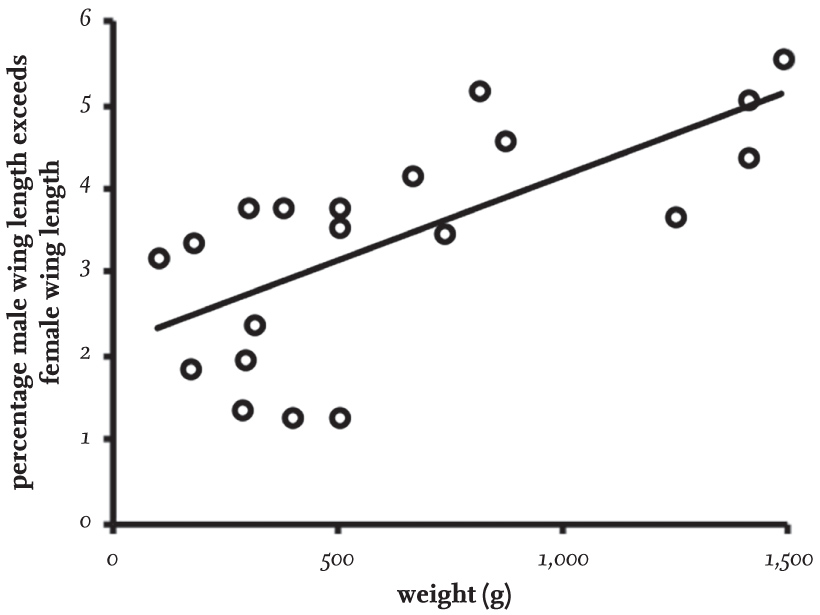

Standard measurements of wing length also tend to be longer in males than in females, but the magnitude of the difference is much smaller, ranging from 1 per cent in some small species to 6 per cent in the largest species (Fig. 6). Even when this difference is converted to wing area, it still results in the wing loading being higher in the large gulls, which explains why these species typically have a more laboured flight, with a slower, more powerful wing-beat. The small gull species, which are of similar weight to many tern species, have a characteristic buoyant flight similar to that of terns.

FIG 5. The percentage by which male gulls of several species are heavier than females, based on data for seven well-studied species. It is evident that there is a much greater difference between the size of males and females in the larger species of gulls.

FIG 6. The relationship between adult weight and the extent to which the male has a longer wing than females. The percentage difference in wing length between the sexes increases in heavier species, but is much less than the difference of body weight shown in Fig. 5.

The reason why there is a greater size difference between the sexes in large gull species is not known, and currently it is possible only to speculate. Perhaps there is a greater need in the large species to reduce competition for food between the sexes, or perhaps the dimorphism is related to the greater need for males of large species to defend nesting territories. The reader might speculate further, bearing in mind that in the skuas, females are invariably larger than males, while male terns are only 1–3 per cent heavier than females.

Despite the average size differences, there is an overlap in the range of sizes of male and female gulls. Niko Tinbergen claimed that, despite the overlap in size between the sexes of Herring Gulls, invariably the male is larger in every pair. Because of the average difference in size between the sexes, by chance the male will be larger than the female in many pairs, and more so in the larger gull species, but I have not found evidence that the male is invariably larger than the female. Size, and particularly the size of the bill, may play a part in individual birds recognising the sex of other gulls, but it is more likely that behaviour – particularly during courtship – plays the major role in sex recognition in gulls, especially in smaller species.

Sexing gulls

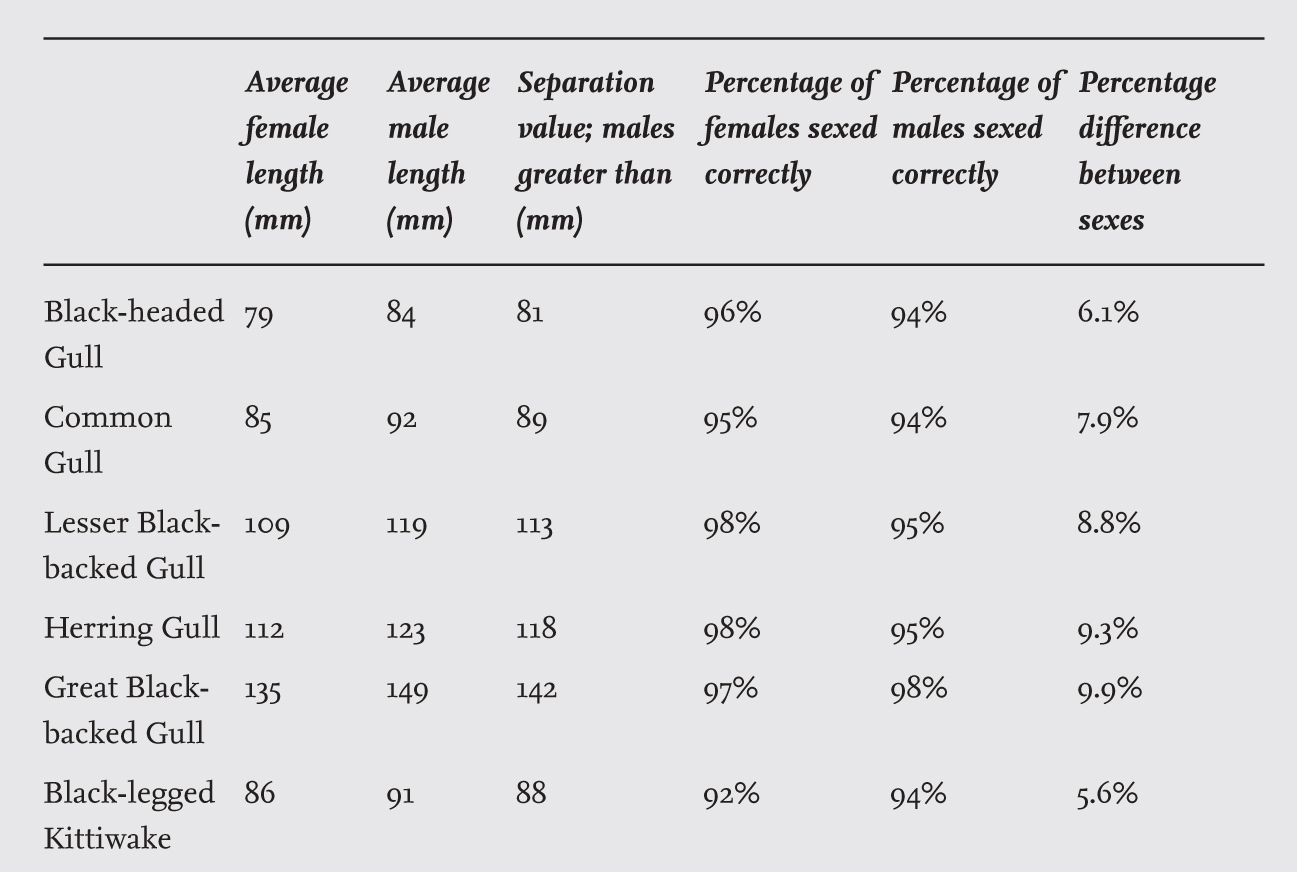

As male and female gulls have identical plumage features, distinguishing them in the field can be very difficult. The most reliable way to determine the sex of an individual bird – without killing it and then dissecting it to examine the gonads – is by carrying out a DNA analysis on samples obtained from feathers or blood. While this method is highly efficient, it is time consuming and it is expensive when large numbers of birds are being studied. In the field, biometric measurements taken while a bird is temporarily captured for ringing can also be used for sexing the individual. I found that the best measure was the head and bill length (from the back of the head to the bill tip), which also had the advantage of showing the highest degree of consistency when measured by different people. Further, the proportionate difference in head and bill length between the sexes is almost twice that for wing length (for example, 9.6 per cent compared to 5 per cent in the Great Black-backed Gull). The only disadvantage of this measure is that in some museum specimens part of the back of the skull was removed during preparation, which prevents it being used in these cases. As shown in Table 2, the head and bill measurement is satisfactory in sexing 92–98 per cent of individuals of several gull species. Including two other body measurements (wing length and bill depth) in a discriminant analysis increased the accuracy of sexing only by less than 2 per cent points.

TABLE 2. The head and bill lengths of adults of six species of gulls in Britain, the measure separating the sexes and the proportions sexed correctly by this single measurement. The data are based on samples of at least 80 individuals of each sex breeding in Britain, except for Common Gulls (Larus canus), which were captured in winter and so were from unknown breeding areas. Based on Coulson et al. (1983a) and additional data.

When a group of breeding gulls is being studied, the behaviour of marked individuals can be used as a reliable method of sexing. Copulation is totally reliable in this respect, as is courtship feeding of the female by the male and intensive food begging by the female. More details on the methodology used to sex gulls are given in Chapter 12.

Adult plumages

There is considerable variation in the shade of grey on the wing and mantle in adult gulls of the same species, which is evident in birds nesting in the same colony. This is illustrated in Fig. 7, which shows the extent of such variation in Herring Gulls breeding on the Isle of May in Scotland (subspecies Larus argentatus argenteus) and in northern Norway (subspecies L. a. argentatus). Because of the variation, there is overlap in wing shades between the two subspecies of Herring Gulls and most, but not all, individuals can be identified on this basis alone (see also box). Even using more measurements of body size does not completely separate all argenteus males from argentatus females.

In Lesser Black-backed Gulls breeding in the Netherlands (Fig. 7), there is also considerable variation in wing shade, with the palest approaching the darkest shade of Herring Gulls breeding in northern Norway. The darkest shade reported in Lesser Black-backs in the Netherlands is said to fall within the shade range of the subspecies Larus fuscus fuscus, which breeds in eastern Scandinavia and typically has a black mantle and wings very similar to those of the Great Black-backed Gull. The majority of Lesser Black-backed Gulls breeding in the Netherlands have a range of shades found in both the subspecies L. f. intermedius (breeding in north-west Europe) and L. f. graellsii (breeding in Britain).