Полная версия

Gulls

This book is not meant as an identification guide, although some of the salient features of each species and their geographical distribution are briefly mentioned. Those wishing to identify gulls should use one of the excellent field guides available, as listed in the Select Bibliography. The world distributions of all gull species considered here have been fully described in standard identification texts, including the gull sections in volume 3 of the Birds of the Western Palaearctic and volume 3 of the Birds of the World.

It has not been possible to write this book without encountering areas of controversy, which include taxonomy, conservation, and the ability to identify some closely related species and subspecies in the field. Ornithology has thrived on controversy in the past and it will continue to do so in the future. In many cases, disagreement has led to the development of new methods of study and more in-depth investigations. In writing this book, debate has reared its head about where a species is placed in red or yellow categories of conservation concern based on a series of possible criteria, the existence of any one of which is enough to indicate that it is threatened. Some ornithologists feel that the system should be improved, and that a more critical scientific approach is needed to interpret data used to estimate the current risk of extinction of individual gull species.

For the same reason, there is no comment on climate change in this book. While there have been several claims that this has affected gulls, sound evidence in favour of such effects is currently poor and is not supported by evidence that adequately allows other possible causes to be excluded. Increasing studies have been made to estimate the potential risks to gulls from offshore wind farms and the rotating arms of the turbines. At present, most of these are based on informed speculation and such factors as the flight height of individual species and their numbers in the key areas. In the future, this problem will be investigated in more detail and the level of the perceived risk to gulls and other seabirds will be based on actual information, not just models of the situation, but the research is not yet at this stage.

In recent years, the common names of some gulls have lengthened, allegedly to avoid international confusion. Hence, the Black-legged Kittiwake, European Herring Gull, American Herring Gull and Yellow-legged Gull join the Lesser Black-backed Gull, Great Black-backed Gull, Black-headed Gull and Slender-billed Gull, which already have long names. Proposals have been made to change the Great Black-headed Gull to the shorter Pallas’s Gull, while it has been suggested that the Common Gull is changed to the Mew Gull. In this book, as mentioned earlier, Herring Gull is used for the European Herring Gull and the American Herring Gull is referred to in full. Similarly, and as mentioned above, the Black-legged Kittiwake is referred to as the Kittiwake, while its sibling species, the Red-legged Kittiwake (which is infrequently mentioned) is written out in full. In most cases this follows the vernacular English names listed in the ninth edition of ‘The Simple British List Based on a Checklist of Birds of Britain’ (2018). In general, this edition retained names already familiar to most readers.

Statistical tests are important in evaluating differences in quantitative data, but to many the presentation of these and their outcomes are but an irritation. In general, I have commented on quantitative differences only when they have been shown to be statistically significant and so are likely to be real and meaningful, although I have not given details of the tests used.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Much of the information in this book derives from two sources. Some comes from professional research, but much is the result of the activities of amateur birdwatchers who spend their spare time visiting sites where they are likely to encounter unusual bird species or birds in exceptionally large numbers, and who then send the details to local recorders or contribute to national surveys and national censuses. Over the years, the number of observers has increased markedly and systems of notifying others of the presence of unusual birds have developed. Both categories of people studying birds have swelled progressively over the past 60 years, and the information and numbers of records have increased to a remarkable extent. In addition, the methods of identifying and confirming rare species have been increasingly supported by good-quality photographs. Accompanying these trends has been a dramatic increase in the numbers of gulls ringed both in Britain and Ireland, and also elsewhere in Europe. Capturing and ringing adult gulls has increased dramatically in recent years with the development of cannon nets and more frequent visits to landfill sites by teams of ringers. All of these additional efforts are appreciated, for without them, much of the information in this book would not have been available.

I would like to acknowledge the detailed contribution of Alan Dean, both for his detailed analysis of the records of gulls in the West Midlands in England over many years and for the photographs he (and others) have so willingly contributed.

The data used in writing this book has been collected over many years and it is possible here to identify only a small number of the hundreds of contributors. The many research students I supervised and advised have all made appreciable contributions over the years, and many have since made further contributions in ornithology and science in general while holding permanent posts both in the UK and North America. I was fortunate in having such an able set of students who contributed wholeheartedly and consistently to studies often made under difficult conditions. They all willingly volunteered to take part in teamwork as required, often at the most unsocial hours of the day and in adverse weather conditions, all while advancing their own studies.

I owe a great deal to the BTO, not only for the ringing scheme they manage so efficiently, but also for the extensive data they have collected. When I first had contact with the BTO in the early 1950s, it had a small office at the top of a set of outside stairs in a side street in Oxford, with a single salaried member of staff, Dr Bruce Campbell. Here, I acknowledge the trust’s willingness to allow me to reproduce maps of ringing recoveries of gulls and to use the most recently available maps of the breeding season distribution of gulls in Britain and Ireland in 2007–11.

Many people have offered photographs for inclusion in the book, and these have all been credited in the captions. In particular, I thank Nicholas Aebischer, Pep Arcos, Rob Barrett, Colin Carter, Becky Coulson, Anthony Davison, Alan Dean, Andrew Easton, Phil Jones, John Kemp, Mark Leitch, Fred van Olphen, Daniel Oro, Mike Osborne, Viola Ross-Smith, Steven Seal, Charles Sharp, Michael Southcott, Brett Spencer, Norman Deans van Swelm, Thermos (fi.wikipedia), Dan Turner and an anonymous photographer for their photographic help and willing permission to allow their excellent images to be included in this book.

The extensive data set on British seabirds now archived and maintained by the Joint Nature Conservancy Council and readily accessible online is a valuable asset and source of information. My thanks also go to Natural England for granting a freedom of information request concerning culls and licences issued to collect gull eggs.

Help and information have been supplied by many, in particular Nicholas Aebischer, David Baines, Robert Barrett, Peter Bell, Richard Bevan, Tim Birkhead, Bill Bourne, Joanna Burger, David Cabot, Kees Camphuysen, Colin Carter, Keith Clarkson, Ian Court, J. B. Cragg, Francis Daunt, Ian Deans, Greg Douglas, Andy Douse, Steve Dudley, Tim Dunn, George Dunnet, Andrew Easton, Julie Ellis, Mike Erwin, Sheila Frazer, Bob Furness, Michael Gochfeld, Thalassa Hamilton, Gill Hartley, Scott Hatch, Martin Heubeck, Grace Hickling, Keith Houston, Jon Jonsson, Heather Kyle, Susan Lindsay, Roddy Mavor, Jim Mills, Ian Nisbet, Daniel Oro, Ian Patterson, Ray Pierotti, Jean-Marc Pons, Julie Porter, Dick Potts, Richard Procter, Chris Redfern, Jim Reid, Sam Rider, Peter Rock, Robin Sellars, Peter Shield, Robert Swann, Mike Swindells, Martin Taylor, Mike Toms, Andrew Tongue, Mike Trees, Daniel Turner, Sarah Wanless, Matt Wood, Vero Wynne-Edwards, Bernard Zonfrillo and Jan Zorgdrager. Over the years, many others have helped in studies and investigations, and I appreciate the assistance of them all.

I owe a major debt of gratitude to my wife, Becky, for the many ways she has supported and helped my gull studies, solved many computing problems, and given help in preparing and checking the text of this book.

CHAPTER 1

An Overview of Gulls

GULLS ARE CONSPICUOUS WEB-FOOTED, long-winged, medium or large seabirds that are readily recognised by the public. Adults are mainly white with shades of grey or black on the mantle and wings. Most species have black wing-tips, some have white ‘mirrors’ within the black areas, but a few species – mainly those restricted to an Arctic breeding distribution – have entirely white wing-tips. In the breeding season, adults of different species either have entirely pure white or very dark (black or brown) heads, and all revert to white heads in the autumn and winter, often with small grey marks behind the eye or grey streaking on the neck.

Gulls are widely known to the public because of their size and the habit of many species to frequent harbours, follow ships, visit landfill sites and visit outdoor areas also frequented by humans, such as seaside resorts, sports fields, beaches, rivers, picnic areas and large car parks at shopping complexes. In recent years, they have become even more familiar in parts of Europe and North America because their numbers have increased and several species have taken to nesting on buildings in urban areas. This habit of urban breeding has developed independently several times in different countries during the twentieth century and has spread rapidly. Urban nesting is now occurring in several species, and has almost certainly arisen through the marked increases in the size of gull populations, coupled with the increased protection given to them over the last century. The presence of gulls in urban areas has been given considerable adverse publicity, including reported cases of adults protecting their unfledged young by diving close to people’s heads, or of gulls snatching food from unsuspecting members of the public. Such reports have resulted in gulls, and particularly the large species, acquiring pest status in certain areas.

EVOLUTION OF GULLS

The Charadriiformes constitutes a single large and distinctive lineage of modern birds, and includes waders, skuas, auks, terns, gulls and a few apparently aberrant species such as jacanas. Although the skuas appear to be similar to gulls, current evidence – including DNA studies – suggests that their ancestry may be nearer to the auks than to gulls.

The lightly built bones of birds associated with flight are fragile and therefore do not often produce good fossil remains. As a result, the evolution of present-day birds is poorly known, and much less so than that of reptiles, fish or mammals. Fossil remains attributable to gulls are particularly scarce. Many of those that have been found have not or cannot be attributed to the presently recognised genera, and certainly not to present-day species. More recently, several fossil bones initially attributed to gulls have been found to belong to other avian groups.

Fossil bones attributed to gulls and possibly members of the genus Larus have been reported both in Europe and the USA from deposits from the Middle Miocene, 20–15 million years ago. The relationship of these fossils to modern-day gulls is unclear; fossilised bird bones are often, and perhaps uncritically, given different specific names to those of currently existing species, ignoring the fact that the bones of a present-day species vary considerably in size according to sex and locality.

TAXONOMY OF GULLS

Initially, gull species were separated and identified on the basis of plumage, skeletal structure and size. In many species, specimens from different geographical areas held in museums and private collections were often named and given subspecies status based on minor differences in size and plumage, but all too frequently this relied on small numbers collected from only a few localities. Many of these named subspecies are still used today and, while the majority are probably justified, others that were described and named many years ago should be re-evaluated using modern techniques and larger samples. Some subspecies have already been rejected on this basis, and it is likely that others will not stand critical re-examination and will also be rejected.

In other cases, some existing subspecies have been promoted to the status of a full species, as has occurred recently within the Herring Gull complex in Europe and Asia. Still others may show only gradual changes in size, structure or plumage shades over their geographical range, a concept not recognised by early taxonomists until Julian Huxley applied the term clines to these groups in 1942. Such clines have already been demonstrated for the Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), the Puffin (Fratercula arctica) and the Common Guillemot (Uria aalge) breeding in the North Atlantic. Questionable subspecies of gulls still exist, and some are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Initially, the eighteenth-century taxonomist Carl Linnaeus placed all gulls in the genus Larus, and most species remained there in what became a very large taxon. Eventually, the two species of kittiwake were removed from Larus and placed in the genus Rissa, while the Ivory Gull was moved to the genus Pagophila (P. eburnea), Sabine’s Gull was transferred to the genus Xema (X. sabini), and Ross’s Gull was placed in the genus Rhodostethia and then, more recently, to Hydrocoloeus (H. rosea), alongside the Little Gull (H. minutus). The Swallow-tailed Gull became the sole species in the genus Creagrus (C. furcatus). These separations were not unreservedly accepted, however, and as late as 1998, Philip Chu proposed returning all gulls to a single genus, Larus. Seven years later, the intensive study of the mitochondrial DNA of many gull species made by Jean-Marc Pons, Alexandre Hassanin and Pierre-Andre Crochet (2005) moved in the opposite direction and separated gulls into nine genera, and in so doing created the new genera Chroicocephalus (with 10 species worldwide), Hydrocoloeus (with two species) and Saundersilarus (comprising only Saunders’ Gull, S. saundersi, in China). Worldwide, at least 24 gull species, especially those with white heads in the breeding season, are still retained in the large genus Larus. Aside from Saundersilarus, three other genera are composed of only one species: Creagrus, containing the Galapagos Islands’ Swallow-tailed Gull; Xema, containing the High Arctic Sabine’s Gull; and Pagophila, including the Ivory Gull, also breeding in the High Arctic. Like Hydrocoloeus, the genus Rissa also contains two species.

One of the major findings made during the in-depth investigation by Pons et al. (2005) was that the gulls that had dark heads as adults did not form a single taxonomic group, as had been suggested by studies made in the second half of the twentieth century, but were composed of three distinct groups of species. These groups were called the ‘black-headed gulls’ and placed in the genus Ichthyaetus, while ‘hooded gulls’ were separated into another new genus, Leucophaeus. The third group, including the Black-headed Gull, were called ‘masked gulls’ and were placed in the genus Chroicocephalus. To an extent, this separation of gulls with dark heads in the breeding season is supported by similar courtship behaviour within each group, as originally suggested by Niko Tinbergen and his co-workers in the 1950s and supported by more extensive recent studies.

GULL SPECIES WORLDWIDE

Currently, there are about 50 species of gulls in the world. This total has increased in recent years and will probably be increased further as improved molecular techniques are used to revise their status; even the definition of a species may be modified or revised. The uncertainty about the precise number of species reflects the fact that the gulls as a group present a taxonomic nightmare, and this has resulted in years of confusion and disagreement. For example, the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) considers the Herring Gull breeding in North America to be a subspecies of the European Herring Gull (Larus argentatus smithsonianus), while the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) regards it as a separate species, Larus smithsonianus. There is still much confusion within the extensive Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex of species and subspecies, particularly those occurring in Asia (see box).

Speciation concepts

The decision as to whether and under what circumstances two populations of animals that occur in different geographical areas can be considered distinct species remains a taxonomic problem, because the level of genetic difference between the two that justifies specific status is often an arbitrary decision and one that is not always universally accepted.

One major taxonomic problem relates to the Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex of subspecies. In 1942, the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr suggested that the subspecies formed a chain around the northern hemisphere, starting with the Lesser Black-backed Gull in Europe, and then further subspecies occurring eastwards through Asia, each having progressively lighter-coloured wings and leading to the American Herring Gull in North America, and finally completing the ring with the Herring Gull of western Europe. The theory is that, by the time this chain of subspecies has spread eastwards around the northern hemisphere and the ends meet up again in Europe, the Lesser Black-backed Gull and the Herring Gull are obviously separate species and interbreed only very rarely. This beautiful explanation of a series of subspecies first spreading, then part of each becoming isolated, allowing the formation of further subspecies around the northern hemisphere and eventually producing two distinct species, was widely acclaimed and has been frequently quoted in books, scientific papers and lectures on genetics and speciation.

However, the recent development and application of mitochondrial DNA techniques has shown that the American Herring Gull is not the closest relative of the European Herring Gull as was previously thought, nor did it spread eastwards historically from North America to Europe to evolve into the European Herring Gull. That said, while the fascinating concept of a ring of gull subspecies spreading around the northern hemisphere and ending with two distinct species has been discredited, it may soon, with some minor modifications, become viable again. This is because the Lesser Black-backed Gull is currently spreading from Europe to North America via Iceland and Greenland, and is beginning to breed in Canada. As such, it is establishing new end points of the chain of subspecies, this time in North America and involving the American Herring Gull.

The Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides), which breeds in Greenland and parts of arctic Canada, has entirely white primaries and is a well-established species, but there is conflict over the status of two similar gulls, Thayer’s and Kumlien’s gulls, both of which show some black on the tips of the primaries. The AOU recognises Thayer’s Gull as a distinct species (L. thayeri), but regards Kumlien’s Gull as a subspecies of Thayer’s Gull (L. thayeri kumlieni). Within Europe, there is considerable disagreement about the status of the three forms, with some national bodies (such as those in Ireland) agreeing with the AOU classification, and others (including the BOU) considering both Thayer’s Gull and Kumlien’s gull as subspecies of the Iceland Gull (L. glaucoides thayeri and L. g. kumlieni). Yet other bodies believe that they represent three distinct species. In this book and without strong conviction on the matter, I have treated Thayer’s Gull as a distinct species but have followed the BOU and regarded Kumlien’s Gull as a subspecies of the Iceland Gull. Fortunately, most individuals that visit Britain are typical Iceland Gulls and lack any black or brown on the wing-tips.

Elsewhere in the world, birds in the Kelp Gull and Dominican Gull complex (currently all known as Larus dominicanus) are similar and obviously related to the Great Black-backed Gull (L. marinus) of the North Atlantic. They are also a taxonomic problem and currently are regarded as consisting of five geographically separated subspecies. Just as some of the former subspecies of the Herring Gull have been recognised as distinct species, some of the L. dominicanus subspecies may also be elevated to species status when more intensive genetic and ecological investigations have been completed.

CURRENT GEOGRAPHICAL RANGES

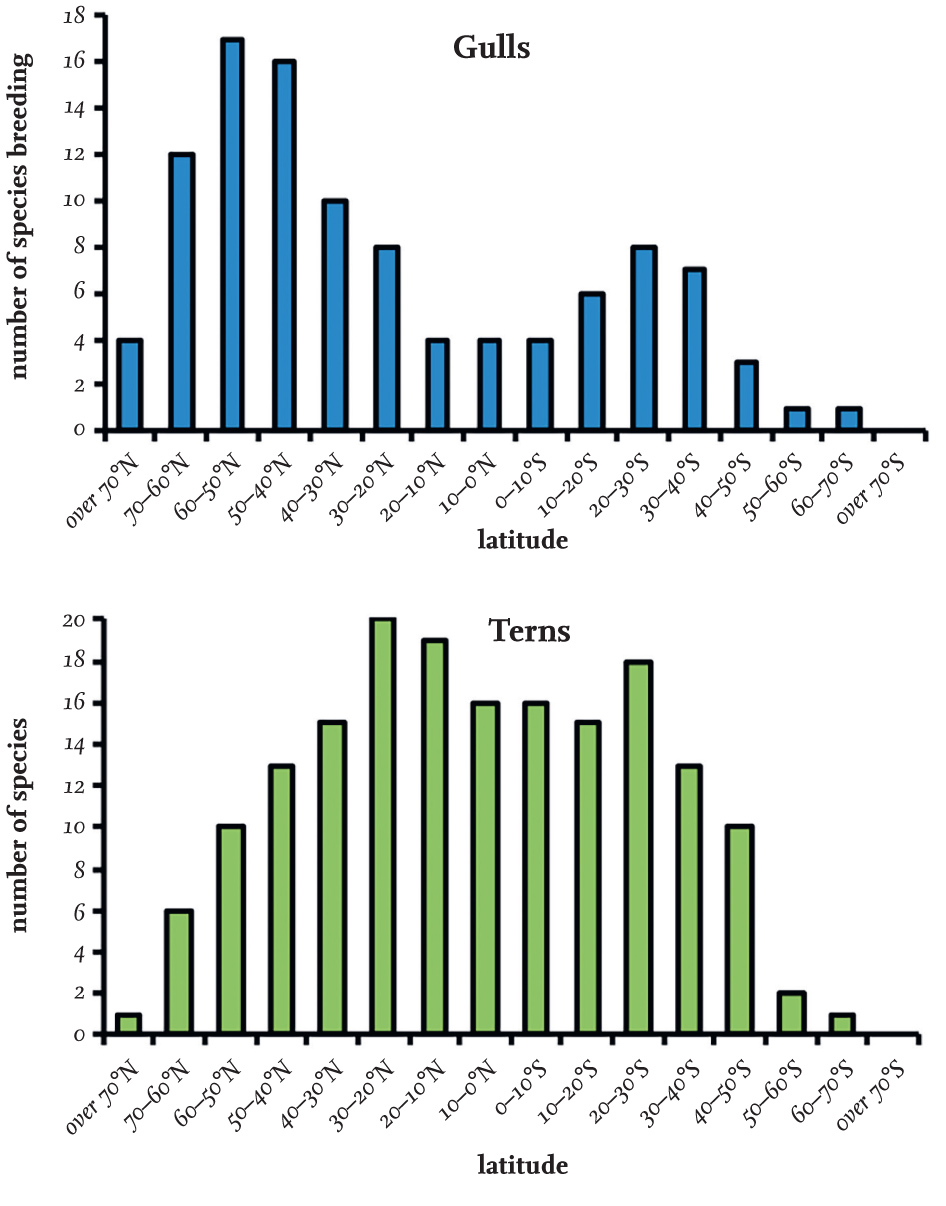

Gulls breed on all continents, with Kelp Gulls extending their southern range into Antarctica and several gull species breeding in the High Arctic. The number of gull species breeding in each 10-degree zone of latitude varies considerably, with two peaks of abundance, one in each hemisphere (Fig. 1). In the northern hemisphere, the number of species peaks between 40°N and 60°N, and in the southern hemisphere, a smaller peak occurs between 20°S and 40°S. Few gull species breed in the tropics, Antarctica or the High Arctic regions. This variation in species abundance, particularly between the two hemispheres, correlates reasonably closely with the amount of land within each latitude zone. This may offer a partial explanation as to why appreciably fewer species of gulls are found and breed in the southern hemisphere.

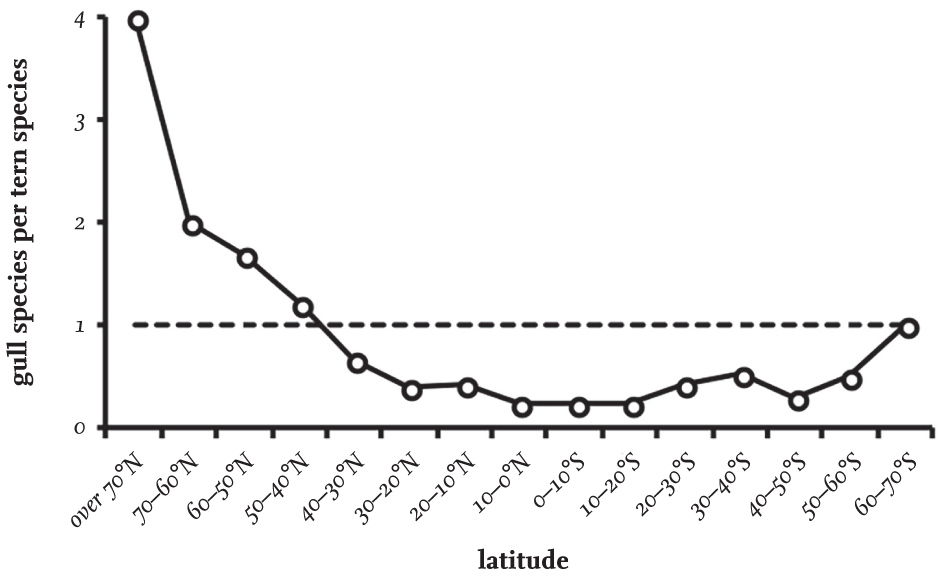

Few individual gull species breed over a wide range, with about 80 per cent spread over less than 20 degrees of latitude, and very few breed in both hemispheres. These patterns differ markedly from the terns, where many species breed in both the northern and southern hemispheres. A comparison of the ratio of gull and tern species breeding in different latitude zones throughout the world is shown in Fig. 2. There are more gull than tern species in only the zones north of 40°N, which begs the question as to why fewer gull species occur in the other zones. Could this be the result of competition between gulls on the one hand, and with petrels and shearwaters in the southern hemisphere?

FIG 1. The number of gull species (upper graph) and tern species (lower graph) breeding throughout the world in each zone of 10-degrees latitude. The distribution of gull species is clearly bimodal, while that for tern species peaks in the tropical zone between 30°N and 30°S. Tern data from Cabot & Nisbet (2013).

FIG 2. The ratio of the number of breeding gull species to the number of tern species in relation to zones of latitude. Gull species are more numerous than tern species only north of 40°N. The dashed line indicates equality.

The dominance of gulls over terns in temperate and arctic regions of the northern hemisphere is even greater when numbers of individuals are considered. For example, the average numbers of gulls per species breeding in Britain are very much greater than for terns. Using the figures from the national census in Britain and Ireland in 2000, there was a total of 1,810,000 breeding gulls (of seven species), but only 176,000 breeding terns (of five species), indicating a ratio of 10 gulls for every tern. Each gull species was represented by an average of seven times the average numbers for each tern species. Similar large differences are evident elsewhere in Europe and in North America.

The numerical dominance of gull species in the northern hemisphere suggests that much of their speciation occurred there. However, species of the genera Larus, Leucophaeus and Chroicocephalus breed in both the northern and southern hemispheres, indicating that in the past at least one species belonging to each genus must have spread, as breeding birds, across the equator on at least one occasion.