полная версия

полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

We were seated. My seat was at the first desk in the middle row, right across from the teacher’s desk. I had to turn my head very fast not to lose sight of Mama and not to turn away from the teacher for too long. Besides, I had someone to look at sitting at my desk. I shared the desk with Larisa Sarbash, my secret kindergarten love. She was tall and thin with light hair and wonderful freckles sprinkled over her little nose. Shy Larisa didn’t look at me. She sat staring at the blackboard so intently one would have thought it was a movie screen. But I cast glances at her now and then and admired her braids with big white bows that were so fluffy I wanted to grab and squeeze them.

Our teacher, Yekaterina Ivanovna, not very tall and somewhat plump, with short chestnut hair, had a tender singsongy voice and a kind gaze. She said she would be our teacher for three years and that in first grade we would begin studying arithmetic, reading and writing, and we would need to bring to school… At this point, she turned to the blackboard, and for the first time in my life I heard the magic sounds that would later become so familiar: Took-took-sh-sh-sh, took took-sh-sh-sh-sh… And white, straight, beautiful lines began to appear, one after another, with incomprehensible swiftness on the blackboard. I already knew printed letters, but these characters were quite mysterious.

How unexpectedly, how loudly the bell rang in the corridor. It was rhythmic and distinct. It was very special. It wasn’t just a bell but the melodious trill of an unfamiliar bird. The bird seemed to be with us in the classroom, hiding among the desks, and when our first school day was over, it sang out loudly, with joy, as if saying, “Toodle-loo! Congratulations! You’ve become school students! And now you may run home! Toodle-loo!”

Chapter 15. The Dugout

We noticed puffs of black smoke on the way home from school. They were pouring out from where building number fourteen, next to ours, was under construction. Kolya Kulikov and I exchanged glances. Everything was clear without words – they were smoking tar for the roof. We’ll have something to play with today.

Classes at school were over at two in the afternoon. At that time, the school looked like a crowded bazaar right before closing time, or the schoolyard before classes and during the main recess. Boys and girls who walked home from school the same way would get together at the school fence near the road. The events of the day, any interesting incidents, were passionately discussed. Teachers were still of great interest to us first graders.

“My teacher is very strict, awfully strict,” Vitya Smirnov complained.

“Do you mean Maria Grigoryevna?” Vitya Shalgin was surprised. “She’s not strict at all. I know her better; we’re neighbors. You should have mine. No one can even budge in class.”

“And my teacher, Yekaterina Ivanovna, is kind,” I bragged.

“Do you mean the Fat Lady?” Zhenya Zhiltsov, who lived in the military housing, asked.

It had only been a few weeks since school started but we already knew or had thought up nicknames for our teachers. The stout physics teacher was Molecule, the slightly bald drawing teacher was the Immortal Kashey (a folk character who has the secret to eternal life), the slow, plump auto class teacher was Zaporozhets (a car model). Yekaterina Ivanovna had two nicknames, Fat Lady and Kolobok (a fairytale character who is a little roll), because when she walked around the classroom, she waddled like Kolobok rolling down a forest path. Was it the need to embellish our humdrum school existence that aroused our imagination? That way, we spent part of the school day in some sort of fairytale, the characters of which we often made up ourselves.

We walked home chattering and laughing. Of course, we didn’t walk down the asphalt road like everybody else. “Like everybody else” was not for us. We walked across the dusty field, across the abandoned vegetable garden, diagonally, to shorten the distance between school and home.

We didn’t think about why we did it. We were drawn to playing, and the most important thing in our games was overcoming. Each of us felt that everything was in his power. There were no obstacles. And it was absolutely not important that we were the only ones who knew about it.

Here came Vitya Smirnov, a future test pilot. Clear skies, fast plane and altitude were on his mind… and Sasha was a future builder. “I’ll erect a building all the way up to the clouds,” he used to say. We were not so sure, “There are no cranes that tall.” Sasha only chuckled, “I won’t need cranes. What are helicopters for?”

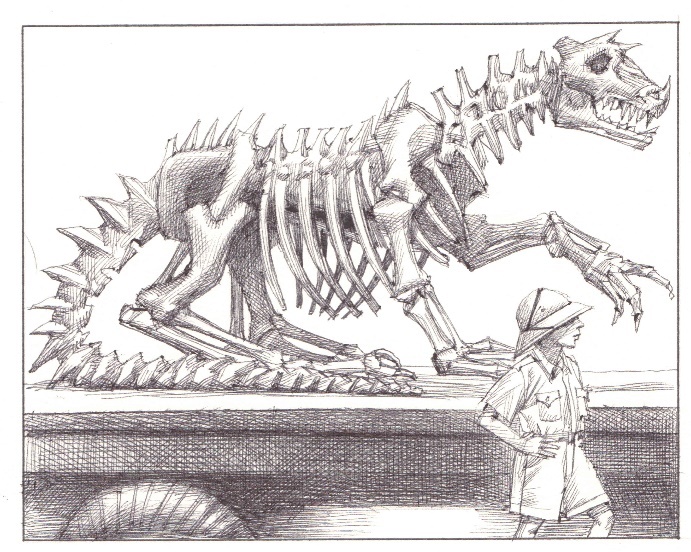

And I dreamed of becoming an archeologist, and a paleontologist at the same time, and digging out the skeleton of the biggest dinosaur somewhere in Africa.

My colleagues and I will dig in the sands of the Sahara for many months, excavating that monster, bone by bone. I will grow dark skinned like a Papuan. I will put the dinosaur together and bring it to Chirchik. I’ll ride in a huge truck through the main streets of our town to the sound of fanfares. My dinosaur will be on the bed of the truck, and I will stand next to it. The city council will declare that the dinosaur will remain in town for good. It will naturally be installed on the playground near my building. Oh, how boys from neighboring buildings will envy me!

The boys, one after another, said good-bye as they reached their buildings. Kolya and I arrived at ours.

“Come out by five,” he reminded me. I nodded.

* * *It seemed that they had decided to construct Building #14 especially for us. We could see something amazingly interesting there at any moment. Here came a dump truck loaded with slabs of reinforced concrete. And right after that, a crane rolled up to it along the rail. It picked up a slab with its mighty claw, lifted it to the floor under construction and tossed it onto that floor effortlessly. Up there, they were waiting for it; they were ready. With our faces raised, we watched how a slab, as if all by itself, without any assistance from the people whose movements seemed so easy, ended up in its place.

Vitya Smirnov watched the operator manipulating the boom of the crane with envy.

“Ah,” he sighed, “if I were him, I would lift the whole dump truck.”

“Are you serious? A crane couldn’t hold such a load. It would topple over.”

An argument ensued. Each of us defended his opinion because we all dreamed of becoming an operator and testing the power of that machine. Of course, we wanted to do it immediately, but if worse came to worst, we planned to enter the special technical school we knew of where they taught that profession, after we finished eighth grade. Meanwhile, each of us pretended to be the master of the crane, capable of moving all those wonderful levers, pushing buttons, switching lights on and off. Just move the lever and the hook would turn. Press the pedal, and the giant would smoothly glide down the rails. Push a button and a load would be lifted. And you just sat in that tower enjoying your omnipotence. You were up there all alone, with just the blue sky and the birds around you. Down below, people wearing helmets scurried back and forth like ants in search of food. Here, they surrounded that crawling caterpillar, the dump truck. They swarmed around it, waiting. Who were they waiting for? Of course, they were waiting for you. You sailed up to them in your enormous crane and attacked that caterpillar…

“It will turn over!” “No, it won’t!” That was us with our hearts in our throats from the fear and ecstasy of watching the team that worked all the way up there, a construction worker who made himself comfortable on the edge of the wall to smoke his cigarette. What could he see from there? Wasn’t he scared?

It was hard to say what was more interesting – observing the frenetic life of the construction site during the day or sneaking to the site after five in the afternoon, when the workday was over.

It only seemed to the builders that the construction site was resting without them. In fact, it was living a secret life from five in the afternoon till late at night. Boys came running like cockroaches from all over the neighborhood. It was dark. Without watchmen and guard dogs, we were the masters with absolute power there.

The construction site was covered with pebbles. We used them as hand grenades. We used tar as camouflage paint, piles of sand became shelters and the cabin of the crane an observation deck. It goes without saying that real “war games” took place right there. Though we sometimes thought up other games or simply wandered around, taking pleasure in our secret ownership of that wonderful place.

Later in the evening when it was pitch dark, high school students often went there. We could hear their voices and see the flickering lights of their cigarettes.

That night, our group crowded around the big blocks of tar. The sun had softened them during the day, and we hurried to tear off large pieces for chewing. We didn’t have any special recipe for doing this. We would just chew pieces of tar, and soon they’d became really soft and elastic in our mouths. It’s true that some experts and gourmets would add paraffin, and that chewing gum was undoubtedly softer and tasted pleasanter. We were all working diligently, chewing our tar. The blocks of tar looked like huge prehistoric hedgehogs.

Then we heard voices. Two tall guys were approaching us.

“Hey, Sipa, is that you hanging out with toddlers? That’s something!” one of them yelled.

Sipa – Sergey Cheremisin, a fifth-grade student from our building – was embarrassed. He had really been enjoying chewing tar in our company. Now he was ashamed of us. But Oleg, one of the guys, displayed magnanimity. “Come with us,” he said waving a bottle he held in his hand. Who would turn down such an invitation? Besides, Sergey vouched for us, “They won’t sell us out.” And he trudged along with the big guys.

A rather deep pit had been dug at the edge of the construction site, a perfect dugout for five or six people.

“Go get some plywood,” Oleg ordered. And we, racing one another, rushed around in search of large, clean pieces of plywood.

“That’s good,” our new leader said approvingly. “Now cover the pit… That’s my boys! Now into the dugout… Wait, wait… We’re one too many.” Oleg glanced around at us and nodded to me. “You’ll stand guard for now. We’ll replace you later.”

Before I had time to utter a word, Oleg had given me a wooden object.

“This is your machine gun. Keep a sharp eye out!”

And they dove into the dugout.

So, I began to walk back and forth, protecting the dugout from a surprise attack with great seriousness.

Time passed. The crimson ball of the sun slid behind the faraway hills and almost disappeared. The outlines of the trees were becoming blurred in the twilight… It grew colder. I could hear laughter coming from the dugout. They were having a good time eating something tasty. It was warm in there.

At last, I made up my mind. Bending over the hole, I shouted, “Hey, it’s been too long! It’s time to replace me!”

“You’re on guard duty!” I heard Oleg’s voice. And then he said, softer, to his friends, who must have been sitting next to him, “What else is a Jew good for? Only to be a guard.”

And I could hear laughter coming from down there. It was sickeningly repugnant, disgusting laughter. It was so far and at the same time so near. It rang in my ears, growing louder, louder and louder. It vibrated my eardrums till it hurt. And I continued to hear in that laughter “Jew… Jew… Jew…”

I was just six, but I knew what it meant. I had heard the word “Jew” when adults talked. I heard about hostility toward Jews in our “harmonious and united” country. But those were conversations about something abstract, about something that was out there, outside my life and had nothing to do with me, couldn’t cause me harm or pain.

Up until today, until this very moment, in this dugout.

My heart began pounding violently. I felt a sharp pain in my chest. I threw down my machine gun and rushed away.

And the laughter raced after me…

Chapter 16. Dog Eaters

I was on the way home from school, skipping and singing. I was singing loudly so that passersby could hear. Let them guess what happy event had made me sing! Today, I received my first grade, and it was an A, for good behavior. It wasn’t difficult to be an A student, I thought. Behave yourself, and that’s it.

My joy wasn’t disinterested. Father had promised that I could go to Kislovodsk in the summer if I finished the first school year as at least a B student. Of course, I dreamed about that trip. And now, the first step had been taken. I had already made some sort of progress in my mind, and Kislovodsk seemed a reality. Really, it was just two… three… eight months before summer, and then I would be there! I could already see the mountains in front of me, the camp hidden among them, the lake, the boats and other wonderful things.

Transported to Kislovodsk, I didn’t notice that I had reached my building, where I saw a bunch of boys at the entrance. Squatting, they surrounded Leda, our yard dog. Her clever eyes always shined like two sunny orbs during the day and two twinkling stars at night. Her raised tail would wag back and forth. Leda was very friendly. She enjoyed our company, and we enjoyed hers. We were generous with caresses. We would pat her little snout and kiss her cold black nose, but we really had to keep an eye on what was going on around us for we didn’t want our parents to see this. We were told all the time that it wasn’t hygienic to kiss and pat a yard dog, or even to play with her. It was useless to argue with adults. It was better to pretend that we sometimes forgot those rules. Besides, our parents were illogical, since many of them liked Leda very much and fed her and all that.

Our relations with Leda had become even closer recently – she’d had pups, and not for the first time. Leda had pups almost every year. It was always a big event for us. She would spend her time in the basement where she kept the pups. Leda seldom left her pups, so some of the boys would visit the dog family. They went there to admire the pups or, when they remembered that it was necessary, to feed Leda. However, those were the older boys, and only a few of them, because it was spooky in the basement. Today, Leda came to the entrance herself, and not because she missed us. Her empty nipples were hanging from her skinny stomach. She needed to fortify herself to feed the pups. Leda was often hungry nowadays. Unlike other dogs, she didn’t wander around the garbage bins in search of food. Leda was squeamish about garbage. She was our yard dog, a member of our society, so to speak, and she knew that. She understood that she got her allowance from building #15.

Each building had its own yard dog, but ours was the best. We were proud of Leda, who was always groomed, without burrs, her coat shiny. She walked in a special way, not like other mongrels, who moved sideways at a hurried trot, looking around cautiously, their thin tails between their legs. Leda was a refined lady, she never hurried, she walked straight and had a bold air about her. Sometimes she allowed herself to waddle, wagging her bottom. If male dogs could whistle, they would undoubtedly have whistled upon seeing that flirtatious beauty, “Wow, what a looker!”

Yes, Leda was attractive. Perhaps that’s why she had pups every year.

We were watching with pleasure as Leda swallowed pieces of sausage when we suddenly heard a piercing cry, “Dog eaters!”

Vitya Smirnov, disheveled and flushed, came running to our entrance with that shout – he lived in the neighboring building – and ran away, probably to inform his own people. Indeed, not a moment had elapsed when a small truck appeared around the corner. It was a disgusting truck. We hated and feared it along with those who drove it. They were “dog eaters,” a team that went around catching stray dogs: that was what our Leda was considered.

Apartment buildings had no right to keep such dogs. Residents couldn’t even protest against these treacherous raids. That was the problem. We boys were the only defenders of the animals.

We knew the hustlers in the truck very well. They called on our parts quite often. We waged a “guerrilla war” against them year after year.

The guy with the indifferent blank expression on his round physiognomy was behind the wheel. He was short and moved around clumsily on his bowlegs, as if he were about to stumble on the smooth surface and take a tumble. His buddy, his face covered with stubble and a crumpled cigarette between his lips, always wore high boots for some reason.

Many a time we watched with disdain the way the dog eaters acted. After siting yet another victim, they would pop out of the truck and try to throw a kind of lasso made of thick, twisted wire over a dog’s head. The noose smelled of death. It looked especially terrible when it was around a dog’s neck.

The residents of our building could hardly be gladdened by that sight, except the secret sadists among them. Dog eaters were cursed at. Attempts were made to shame them.

“What do you teach kids? To kill animals?” someone asked mournfully from a veranda.

“I’m sure you use soap,” the unshaven one usually answered.

“And what will you say if one of them bites your child?” the dimwitted one asked.

They said the dogs were used to make soap. The boys thought it was nonsense. Couldn’t they possibly come up with a different way to make it? So many things had been invented, and soap must have been made of chemicals. And if it was true that dogs were used to make soap, it would be disgusting even to touch it. You would wash your hands and think, “These suds could be our Leda.”

Besides, we kids had a serious suspicion. To be precise, we were sure that the dog eaters were catching animals in order to feast on their meat. That’s why we called them dog eaters.

“Why not? It’s very simple,” we discussed the cause of dog eating. “There’s often no meat at the bazaar. That’s why they try to catch poor dogs. They skin them and chop the meat into pieces. They eat it themselves and take some of it to the bazaar. Just try to tell dog meat from mutton.”

Aroused by such ideas, our hatred of the dog eaters grew boundlessly. Unlike the adults, all of us, especially those who were older, did not limit ourselves to verbal altercations with our enemies. We devised different methods of defense and keen plans for revenge. While the dog hunters were trying to catch their prey, we boys would either puncture the tires of their truck or stick matches into the ignition. Once, we even managed to open the truck and set almost a dozen dogs free. And later, hiding in the hallways, we writhed with laughter as we watched the dog eaters’ growing rage.

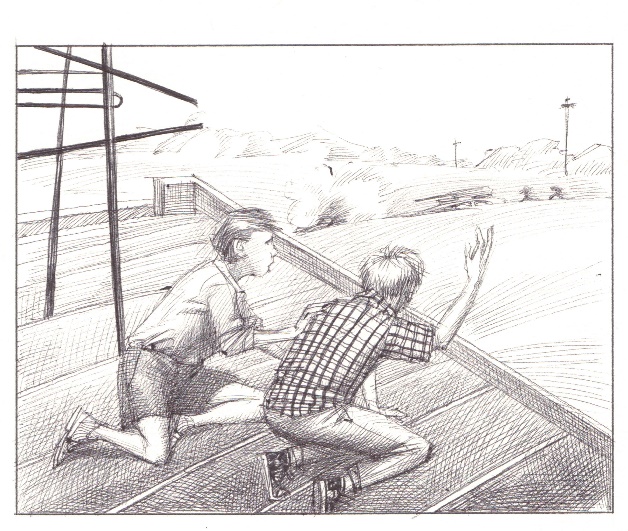

Of course, as they were arriving, our first task was defense. We had to make our plans in advance, and they had to be carefully thought out. Today’s tactic was clear – hide in the basement, that very basement where Leda fed her pups.

We retreated, like the Spartans, forming a triangle, holding our briefcases out like shields, with Leda in the middle. We safely reached the third entrance, where there was a staircase leading to the basement. Going down there with Leda was not as scary as going by ourselves, but still… many of us, including me, were afraid of the basement. Its dark expanse stretched under the building for its entire length and was lit only by sunlight streaming through small windows in the back wall. Besides, the ceiling was low, and we had to bend over to walk.

The darkness and desolation made the basement a perfect refuge for all kinds of riffraff who would stay there overnight, or sometimes even live there. An alcoholic who was drinking like a fish stayed there until he sobered up; a homeless hobo lived there for a month or so until he was chased out. It would be all right if it were just that, but the high school students talked vaguely about evil spirits and ghosts.

“Once I stood there…” Sipa was telling us, “smoking. Suddenly, I looked around and saw ‘it’ staring at me with its glowing eyes. And it was mumbling as if it had been wounded… I don’t know how I managed to escape.”

“That was a homeless drunk,” his friends laughed at him. “He was asking you to help him cure his hangover, but you didn’t understand him you were so scared. You can’t be serious!”

They laughed all right, but it gave us the creeps.

* * *Leda ran in front of us as we walked in single file, looking around, even though it was absolutely dark. We hadn’t equipped ourselves with flashlights – that was a big mistake, since it was difficult to walk in the basement without stumbling, even with flashlights. You could come across anything there – pieces of pipe, chunks of cement, bottles, various types of garbage, not to mention dried up human excrement. But we walked and walked and walked. Leda’s shining eyes showed us the way that she knew very well.

The pups, all seven of them, lay on the rags by one of the windows. We could get a better look at them there. They were tiny, and they poked each other with their wet little noses, yelping softly. How aminated they became when they smelled their mother. Pushing each other impatiently, they crawled to her belly. It wasn’t far to crawl. As soon as Leda reached them, she would sniff them without fail and lie down on her side.

We grew quiet. All we could hear was the smacking of their lips.

Suddenly, a match was struck a few steps away, by the wall. Someone uttered a cry. We didn’t even have time to get scared, as the flame illuminated Oleg’s face.

“Who are you guys hiding from?” he asked.

“From the dog eaters!” and we began to tell him about our recent “battle,” interrupting each other.

Leda was a participant in the conversation. She whirled at Oleg’s feet, yelping quietly and wagging her tail. Leda liked Oleg. He had been ready to fight to defend her many times. Dogs can discern people’s good qualities better than some humans.

“We should have burned their shed long ago,” Oleg mumbled, after listening to our story about the dog eaters.

The idea received enthusiastic support, but he never got a chance to burn down the stand.

Saying good-bye to Leda and the pups, we never imagined that we were seeing our dog for the last time, but that was what happened. Leda disappeared the next day. No one knew what had happened or how it happened. And the dog eaters never showed up again.

We ran through all the yards in the neighborhood. We asked everyone, children and adults, but no one had caught sight of her. We managed to give two of her pups to nice people, but the other five had to be drowned. Of course, the adults did it, not us.

We didn’t adopt another stray dog. It just didn’t work out. We also didn’t want to be unfaithful to Leda, for we hoped she would come back one day.

Chapter 17. A Gulp of Life

The caterpillar tracks of tanks rattled, booming shots rumbled, the barrels of cannons gave off smoke. It was just another exercise underway on the training ground of the tank school. We watched the “battle” with agitation, ecstasy and envy from the roof of our building.

We were really lucky to live in this building. We were so lucky that all the boys in town envied us. A huge plot of vacant land began behind our building and stretched for a few kilometers up into the hills. The tank school was located at the edge of that plot. The training ground where the tank exercises were carried out wasn’t far from the school. Well? Is it clear now why we were lucky? We could watch that wonderful spectacle – which was sweeter for us than any movie about war – from the roof of our building, as if from the stands of a stadium. Were we capable of simply watching? Actually, we were not on the roof but on a hill from which, as representatives of General Headquarters, we directed the battle.